Easter Eggs You Missed In Joker

From subtle references to past storylines to obscure characters filling up supporting roles and all the way to world-shattering artifacts looming ominously in the background, superhero movies are full of Easter eggs, just waiting for obsessive fans to find them. 2019's Joker, however, is different. As you may have heard, it's not your typical comic book movie, and as a result, it doesn't have your typical comic book references littering the scene.

But that doesn't mean that there aren't a handful of subtle and not-so-subtle references to films, real-world events, and even the silent art of mime lurking in its grim and gritty Gotham City streets. If you're still reeling from the violence and drama of Arthur Fleck's tragic journey, read on to find out about the little things you might've missed. Be careful, though: if you haven't seen it, there are a ton of spoilers following... no joke.

The Joker is still the Man Who Laughs

If you know one piece of trivia about the Joker, it's probably that he was originally inspired not by the playing card from which he took his name, but by Gwynplaine, the main character of the 1928 silent film The Man Who Laughs. In the movie, Gwynplaine, played by German actor Conrad Veidt, is a child in the 17th century whose father is killed by rival noblemen. Before they put his father in the Iron Maiden, though, they disfigure his face into a permanent smile, leaving him unable to ever truly match his face to his emotions. Also, Gwynplaine's father was betrayed by — wait for it — his jester, whose "jests were cruel and his smiles were false." Sound like anyone you know?

Fittingly enough, this cinematic inspiration made its way back to the movies in Joker. The parallels to Arthur Fleck's medical condition, which causes him to compulsively laugh whenever he's under stress, are obvious, as is the reveal that his mother ignored his severe childhood abuse because he was "happily" laughing through the horrific ordeal. It's more than just the subtext, though — one Easter egg is a visual nod to a specific shot from The Man Who Laughs that recurs several times in Joker.

Throughout the film, including in the opening sequence and, notably, at the end, Fleck forces a "smile" onto his face by hooking his fingers into his mouth and pulling upwards. This is exactly the same thing that Dr. Hardquannone does to show Gwynplaine's father how his son has suffered. Perhaps more importantly is the fact that Fleck does this same thing to a young Bruce Wayne when he's trying to get access to Thomas Wayne — the lines immediately after that shot in The Man Who Laughs explain that they did it so that Gwynplaine would "laugh forever at his fool of a father." Given the dynamic in play between Fleck and the Waynes, there's actually way more to it than just the supremely creepy act of putting your hands in a child's mouth.

The Joker's Modern Times

The Man Who Laughs isn't the only silent movie to have its influence felt on Joker. It's difficult to imagine a Gotham City where putting on a well-publicized showing of a famous Charlie Chaplin comedy that seems to be attended solely by billionaires wouldn't immediately be recognized as a truly terrible idea. Joker, however, takes place before Gotham was overrun with the kind of thematic criminals who leave clues disguised as crossword puzzles and poison comedy clubs with deadly smile gas, so it probably seemed like a good idea at the time.

Still, it raises the question of why Modern Times was chosen for a sequence in the film, and was featured so prominently that we stop to watch Arthur Fleck as he watches one of its most famous gags. There's an obvious level, of course; the scene in question involves Chaplin's character roller-skating blindfolded, nearly falling over a ledge into a precipitous fall, a pretty on-the-nose reinforcement of Fleck as a man teetering on the edge of sanity.

If you're familiar with the rest of Modern Times, though, you'll realize that some of its themes are Easter eggs mirroring the ones we're seeing play out for Gotham City. This is, after all, a film where Chaplin, as the Tramp, is dealing with a desperate economic situation, finding himself literally chewed up and spat out by the machinery of heavy industry. Even more telling is the scene where he's arrested and sent to jail before being pardoned, only to argue that he'd rather stay in jail than go back out and face the alternative. That's a sentiment that's echoed in Joker by Brian Tyree Henry in his minor but crucial role as a file clerk at Arkham State Hospital, who tells Arthur that some people are better off locked up there than out on the increasingly dangerous streets of Gotham City.

The Joker's Scorsese connection

Saying that director Todd Phillips was inspired by Martin Scorsese in Joker is sort of like saying that life on Earth is "inspired by" the sun. It's basically accurate, but it would be a little more accurate to say that one was entirely dependent on the other and would not exist without it. There's a very significant amount of Taxi Driver in the DNA of Joker's broader plot points, from Arthur getting the handgun from his coworker, Thomas Wayne's political ambitions, and the grimy feel of Gotham City. It's not the only Scorsese picture in play, though.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, 1983's The King of Comedy had a huge influence on Joker, to the point where it's worth your time to watch just to catch everything that's going on. See if you can spot the connections here: Robert De Niro stars as Rupert Pupkin, an aspiring stand-up comedian obsessed with talk show host Jerry Langford. Pupkin often has vivid fantasies, which are never clearly delineated for the audience, of being on Langford's show and even being friends with Langford himself. Eventually, his obsession leads him to kidnap Langford, holding him for ransom until he's allowed to be a guest on the show, where he tells a few jokes about his crime, confessing to the audience in the guise of a stand-up routine.

If you've seen Joker, you should be experiencing a powerful feeling of déjà vu right now, but the exclamation point on the Easter egg comes in De Niro himself being cast as Murray Franklin, the talk show host with whom Fleck is obsessed. Naturally, he winds up being caught up in Fleck's madness, even accidentally giving him the name "Joker." The parallels are strong, even if Joker turns out to be significantly more homicidal than Pupkin was.

The Maskmaker

The motif of Arthur Fleck dancing recurs throughout Joker, from his halting, Oedipal waltz with his mother all the way to the final moments of the film, when he celebrates another successful murder by busting a move in Arkham, but there's one moment where it seems different. After his first trio of kills, when he's collecting himself in a dimly lit bathroom, Fleck's feet sweep across the floor, leading his whole body into a long routine. The thing is, it doesn't look like the dancing we see elsewhere in the film. It's more fluid, and seems more theatrically performative.

So what's the deal? Is he turning to interpretive dance to express his joy at gun violence? Is he testing out his other potential criminal identity, the Pop-n-Locker? Is he re-centering himself with some post-murder Tai chi? It's possibly all three, but there's another possibility that might seem just as far-fetched: the filmmakers could be evoking the fluid movements of legendary French mime Marcel Marceau.

If that sounds like a long shot, that's because it is, but consider this potential Easter egg: one of Marceau's most famous performances was The Maskmaker, in which he pantomimed putting on a series of masks, changing his expression to match. The climax of the piece comes when Marceau finds that a "mask" depicting pure, wide-eyed joy has become stuck on his face. He struggles to remove it, trying to peel off what seems like his own skin as his body contorts with pain and depression, all while his face remains locked in the painted smile of a clown. If that doesn't sound like what's going on in Joker, then we don't know what does.

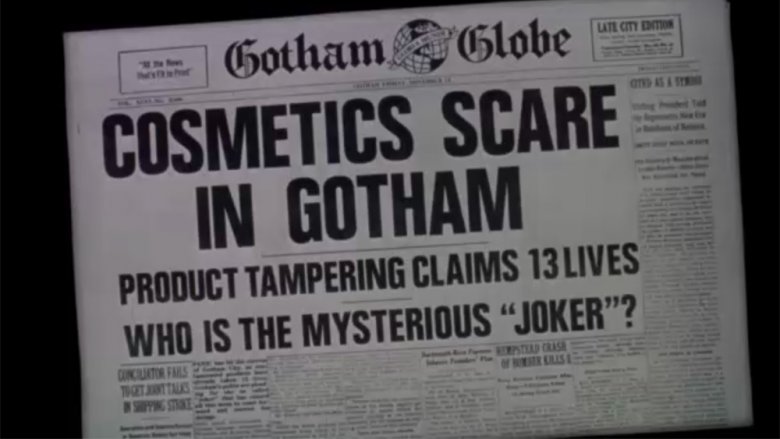

Cosmetics and drugs

Sometimes, a sign is just a sign, but let's assume for a moment that every single thing in every single shot of a film is a very deliberate choice put there by the creators. If that's the case, then there's something in the early moments of Joker that may have a little extra Easter egg-type significance. Shortly after we're first introduced to Arthur Fleck, he goes to get his medication from a drugstore, and walks past a window with two words written in neon: Cosmetics and Drugs.

On the surface, well, there's only so many things a storefront drugstore has in stock to advertise, and those are pretty common things to find. Slightly beneath that reading, though, we have the idea that for Arthur, the drugs he's taking are a form of cosmetics. It's mental makeup. His medication is clearly ineffective; it's only covering up something much uglier underneath, and when he stops taking it, he says that he's his real self. Maybe not the best message to float towards anyone in the audience struggling with mental health issues themselves, but definitely the viewpoint that Arthur himself has. It's also quite in line with how much time the film devotes to showing Fleck actually putting on makeup, and how literally painting his face (and tongue, gross) is the sign that he's become Joker rather than simply Arthur Fleck.

Beneath that interpretation, we have another: that this is actually one of the movie's only references to a previous cinematic Joker. In Tim Burton's 1989 Batman, the Joker's biggest criminal act — before he tries to poison the entire city with parade floats of death, anyway — comes when he terrorizes the city with Smylex. The poison, which leaves his victims smiling and very dead, is hidden in everyday products: hairspray, lipstick, perfume. In other words: drugged cosmetics.

Zex und zex

This might be surprising considering that it's a movie about the Joker — you know, the bad guy from the Batman comic books? —but Joker doesn't really have a lot of specific references to the comics. Other than the major characters, there aren't really any superheroes or villains referenced in the film, unless you count the offhand mention of "super cats" being a deep cut reference to Streaky. There's no hint of Harley Quinn, no Ha-Hacienda or Jokermobile, and sadly, Arthur Fleck never even proclaims that it's time for the Joker's Five-Way Revenge!

There's one major exception, though. While it's pretty clearly an homage to King of Comedy, it's easy to argue that the entire climax of the film is an Easter egg referencing one of the most influential Batman comics of all time: The Dark Knight Returns. In the third issue of Frank Miller's '80s classic — itself a product of the same era that Joker is constantly evoking, with its own set of Taxi Driver references — the Joker appears as a guest on a talk show. It's definitely not a direct homage to the comic and it doesn't line up exactly right; the Joker's at the end of his criminal career rather than the beginning, and instead of the movie's Murray Franklin, the host in the comic is "David Endochrine," an analogue for David Letterman.

There is, however, one clear reference, and it's one that you might've missed if you're not up on your '80s pop culture: Dr. Sally, whose few lines indicate that she's a sex therapist, along the lines of the real-life Ruth Westheimer, better known pop culturally as Dr. Ruth. She was a frequent guest on The Tonight Show and Late Night with David Letterman, and like Letterman himself, there's an analogue for her in The Dark Knight Returns, too. It's not just her presence that makes the reference clear, though, it's the theatrical and incredibly creepy kiss that Joker plants on her as he enters the scene. He does the same in the comic, except there, his lipstick is laced with poison that leaves her as one of his signature smiling corpses.

The Joker's hidden figure

Joker marks the sixth time that a live-action Joker has been featured on the big screen. The first five times — 1966, 1989, The Dark Knight, Suicide Squad, and Mask of the Phantasm, if you're keeping score at home — all featured very different designs, but that all drew from the same source. You'd never confuse Cesar Romero's Joker with Heath Ledger's, but they've both got green hair and purple suits, and even Jared Leto's purple snakeskin coat keeps the color scheme going.

Joker, on the other hand, breaks with tradition. Rather than the traditional purple, Arthur Fleck's emergence as the Joker comes with a slightly different look. The green hair is there, and the traditional three-piece suit, but rather than purple and green, it's more of a burgundy. It's a small difference, and the most likely explanation is that Todd Phillips, Joaquin Phoenix, and costume designer Mark Bridges wanted their take on the character to be visually distinct from the others, which was probably a good idea given a few strong similarities to Heath Ledger's look.

But there is one place where you can find this color scheme on the Joker, and it probably isn't where you expect. Back in 1990, the Kenner toy company was riding the wave of the '89 Batman movie when they released "Sky Escape Joker." It's not quite the same costume — the vest and shirt colors are switched — but the color of the jacket is shockingly similar to what wound up in theaters 29 years later. Does this mean that there was a draft of Joker in which Phoenix flew around on Sky Escape Joker's backpack helicopter? Probably not, but hey, you never know. Release the Sky Escape cut, Warner Bros.!

Arkham State Hospital

The fact that Arkham Asylum shows up in a movie about the Joker isn't exactly an "Easter egg" in itself. Given that Gotham City's extremely ill-equipped home for the criminally insane is almost as prominent as the Dark Knight himself in the greater Batman mythology, it might even be more notable if a Batman-adjacent project hit screens without mentioning Arkham at all.

There is something about this particular Arkham appearance that's worth noting, though: it's not Arkham Asylum, it's Arkham State Hospital. That might seem like a relatively minor change that was made in order to seem more realistic — "Asylum" as a term for a mental hospital would've fallen out of favor decades before Joker's mid-'80s setting — but there might be something more going on. Before it was the gothic mansion with a hundred gargoyles and a revolving door for costumed criminals, the Arkham of the comics was simply "Arkham Hospital," which was itself a reference to H.P. Lovecraft. That's what it's called in its first appearance in Batman #258, complete with a building that appears to be a slightly more realistic facility than the spooky house it would become.

What makes it even more notable is Arkham Hospital's first two residents. The only pair of super-villains we see confined there in that issue are Two-Face and, of course, the Joker. The only snag is that Two-Face actually appears first, and it's not until he's making his escape that he runs past the Joker's cell. That said, if you really want to get granular, Batman #251 — the first new Joker story in Batman or Detective Comics in four years — mentions that the Clown Prince of Crime had recently "escaped from the state hospital for the criminally insane." If we assume that's Arkham, and that seems like a safe assumption, then Joker is in fact the first character to be locked up there, and Two-Face is the second. And that's just as Harvey Dent would want it to be.

The Joker's Bernie Goetz

Joker pulls a big portion of its aesthetic from New York City in the mid-'80s, and not just because it's evoking the grimy, crime-ridden streets of Taxi Driver and The King of Comedy. There are real-life incidents forming the background for the events playing out on the screen, including the massive spike in crime that accompanied the crack epidemic, and a "garbage strike" that's based on similar sanitation worker strikes in New York, like one that lasted 17 days in 1981.

The one incident most heavily referenced in the plot of Joker is the 1984 shooting of four men in a subway car by Bernie Goetz. Goetz claimed that he was defending himself from a robbery, and was initially dubbed the "Subway Vigilante" by media before he turned himself in. Many New Yorkers, as well as people following the story from elsewhere, were supportive of Goetz's actions, viewing them as a justified response to the seemingly unchecked rise of violent crime.

Eventually, though, public opinion turned against him, largely because of the view that Goetz had been racially motivated — all four men shot by Goetz were black, Goetz himself was not — which was supported by racist statements Goetz had made in the past. Also, Goetz was later quoted as saying that after he shot the four men, he "was gonna gouge out one of the guys' eyes out with my keys" and that he only stopped shooting because "I ran out of bullets." While there were plenty of people willing to indulge in Death Wish-style revenge fantasies, those are the kind of statements that make them think you might not be all that stable to begin with.

It's no accident, then, that Arthur's transformation into Joker begins with shooting his assailants on a subway train, and that he only stops shooting because he runs out of bullets, or that his actions are sensationalized by the media and approved of by others in Gotham City.