Dumb Things In Die Hard Everyone Ignored

It is a truth universally acknowledged that Die Hard is a perfect movie. Action movie, Christmas movie, semi-comedy movie, whatever you want to call it, it's perfect. Though it opened to tepid response in 1988, time has cemented John McTiernan's action film as a treasured American icon. It's endlessly quotable and instantly recognizable when visually referenced. That's the kind of immortality any filmmaker dreams to achieve.

Of course, that's not to say that Die Hard is 100 percent flawless. But hey, the artistic effectiveness of a film can absolutely be measured by its capacity to hand-wave over real-life complications and outright hysterical probabilities that get in the way of fantasy. This is something at which Die Hard excels, and it's worth digging into why we don't care. We're not here for just another silly nit-pick hunt for "plot holes." There are concepts in Die Hard that, when considered with a more rational mind not entertained by gratuitous explosions and bantery dialogue, actually are pretty dumb. However, despite the few mistakes, we can't help but love the movie anyway.

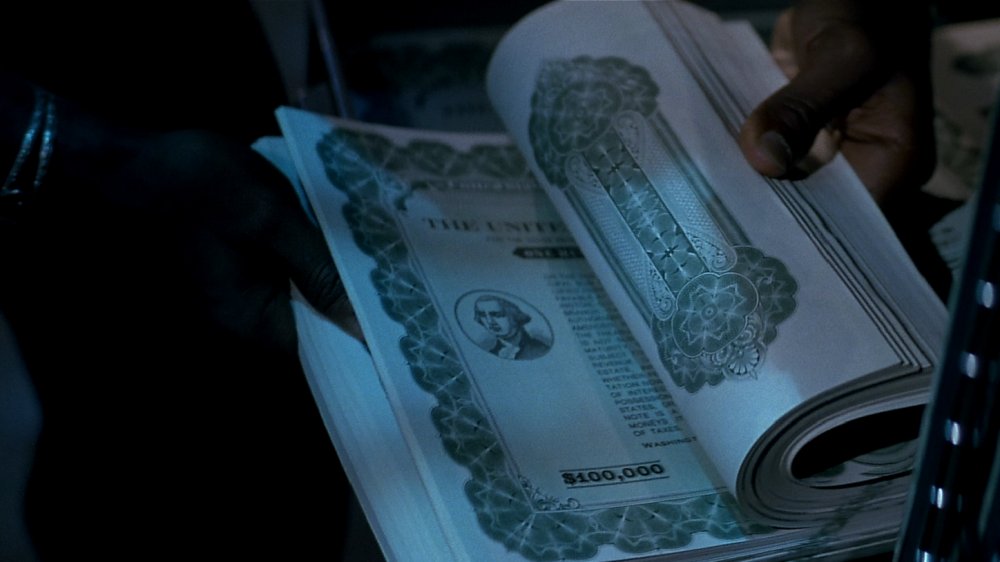

The bonds plot is shaky at best

While Die Hard is a fantastic action movie, we've got to talk about those bearer bonds. See, negotiable bearer bonds, the MacGuffin at the heart of Hans Gruber's robbery, were pretty much made legally obsolete in 1982, five years before we can reasonably assume Die Hard is supposed to take place (1987-1988). And then there's the issue with their value. You can clearly see the character of Leo fan the bearer bonds once they enter the vault in the third act, revealing they're initially valued at $100,000. However, Gruber refers to them earning "20 percent," and no US-issued government bearer bond was ever valued above $10,000, and the corporate bond interest rate in 1987-1988 was about nine percent. And sure, Nakatomi could conceivably hold some since the legislation had been passed in a relatively contemporary age, but they would be pointless for business transactions due to their reputation as being used for investment fraud.

On top of that, a negotiable bearer bond must be presented to a bank and in person to redeem the full valuation when the bond reaches maturity. Even the interest coupons that can be detached and cashed in require the same prerequisite because negotiable means "whoever is literally holding the bond in their hands at the time of redemption." Even if you succeed in your supposed fake-death plot, that's gonna fall apart pretty quick when you show up at a bank — a heavily-monitored public place — with fat stacks of negotiable bearer bonds that recently were made functionally illegal precisely because they're used for white collar crime.

However, we as an audience couldn't care less, because most moviegoers don't know anything about high finance. Plus, throwing the concept of a bond into the script rather than cash makes it sound white-collar and sexy, and it works.

Argyle's entire existence is kind of dumb

The character of Argyle exists in Die Hard's script for precisely two reasons. The first is getting John McClane to Nakatomi Plaza with some lovely establishing shots, and the second is knocking out Leo when he attempts to escape in at the end of the film. His entire bargain with John when he gets out of the limo (basically, "I'll park and wait until you call me, and if your wife kicks you out, I'll get you a hotel room") isn't just unheard of for a limo driver, but it's fundamentally impossible because it's literally his first day on the job, and he's working off the books, as he tells his girlfriend in the middle part of the film. ("My boss? He thinks I'm heading to Florida.")

Sure, it's common for taxi drivers — which Argyle says was his last job — to work off the books, but that's different from higher-end limo work. Why would his boss permit him to go on vacation immediately after getting hired? Zero percent of this makes any logical sense when thought through. However, Die Hard fans don't really care because Argyle is fantastic. We love and cherish Argyle's wit and levity cut periodically into the film so you won't forget about his existence, even though his purpose, strictly speaking to the plot, is borderline pointless. Die Hard took what could've been a very short and easily forgotten bit of hand-wavey transposition of the protagonist and gave us a character almost as beloved and iconic as both McClane and Gruber.

We have little idea what Nakatomi actually does

Die Hard revolves around a massive business known as the Nakatomi Corporation, but what exactly goes on inside that massive skyscraper? The single clue we get as to Nakatomi's incorporated purpose is when Hans Gruber lists off Joseph Takagi's CV. He says that Takagi has worked for two separate divisions of Nakatomi — in trading sometime in the past and in investments, where he's CEO now. Up in Takagi's penthouse office, we see large models of build-outs for natural gas, crude oil, and the futuristic highway bridge "for Indonesia." These could indeed be projects in which they supply capital as an investment company, but Takagi treats them very personally, as if Nakatomi is doing all of this by itself.

Gruber goes on to say that the $640 million in bonds constitutes "ten days operating cost" for the company, which totals to roughly $12 billion — again, operating cost — a year. This is supposedly an American subsidiary of a Japanese company in 1987 dollars, so that would be roughly $27 billion today. For perspective, AIG, one of the nation's largest fiduciary companies, reports $47 billion in total modern revenue. It's all over the place. However, we as the audience don't really care because those models look very cool and super business-y, big numbers sound very impressive off the cuff, and James Shigeta (Takagi) sells being a CEO like it's breathing.

Why doesn't Hans Gruber know what Takagi looks like?

When Hans Gruber and his gun-toting crew first show up, the German mastermind walks among the crowd of hostages for a solid minute and obviously passes right by Takagi, which is weird considering that just a few minutes later, Gruber lists off Takagi's CV like he's reading the Yellow Pages. The entire scene makes a big deal out of Gruber understanding Takagi's entire professional existence back to, like, high school, but he can't pick his mug out where it's obviously sitting next to the fountain with maybe two dozen other people? (Holly Gennero's hair alone is awfully large and noticeable right there next to Takagi, even for a film set in the '80s.)

Plus, Gruber rattles off a list of terrorist sects that he's read about in Time, and the guy watches CNN. He absolutely, positively, completely should know exactly what Takagi — a man who almost certainly qualifies as a Fortune 500 CEO and has profiles written about him in financial magazines — looks like and pick him out in such close quarters. However, we don't really care all that much that Gruber can't seem to ID his target. Why? Well, for one, that scene features an excellent series of cuts among the crowd to keep our eyes moving and focused on Gruber. And for another, just the simple drama of the moment entices us all, as it should.

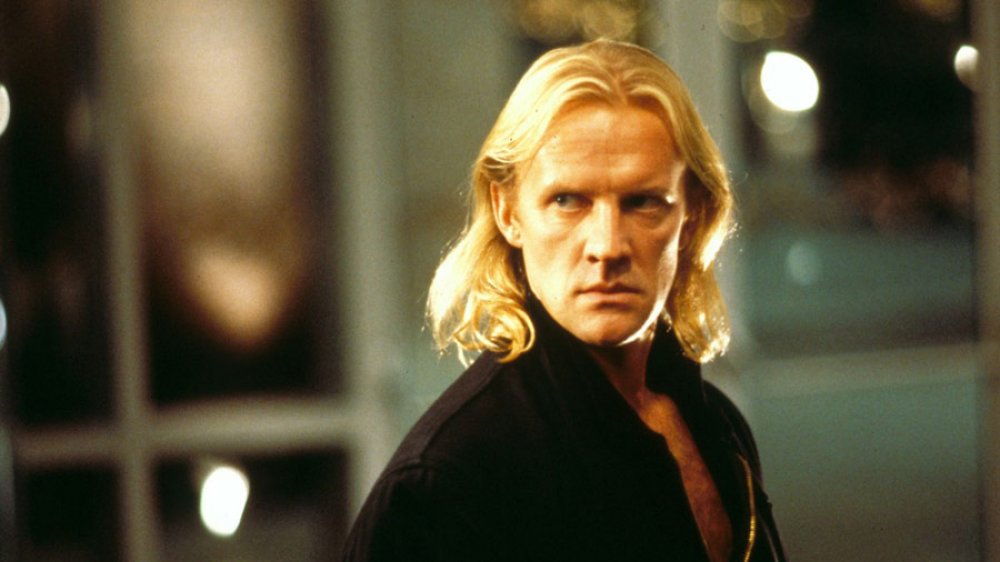

Karl should be extremely dead

During the climax, John finally goes toe-to-toe with Karl, and their fight ends with him wrapping chain around Karl's neck, then electric-sliding him down the stairwell ceiling and into the wall, leaving him to die. That really should be 100 percent it for our favorite murderer. On average, it takes about five minutes to die by this particularly grisly method, and one would lose consciousness due to oxygen deprivation in 30 or so seconds. The movie cuts back to him after what could reasonably be assumed to be five in-universe minutes, and he's still there. That's well past the point where he would've fallen unconscious, and on top of that, it would be nigh-impossible for him to free himself. Of course, at the end of the film, Karl returns in all his bad guy glory, evidently ready for round two with McClane.

However, we don't care about this inconsistency because the entire movie makes the constant stylistic point that Karl is more of a force to be feared than a man. The dude is inevitable as Thanos. Bringing him back at the last second is the cherry on top of that statement, and of course, it pays out on Officer Powell overcoming his fear of pulling his gun in the line of duty.

Die Hard's dumb table

We need to talk about the truly nonsensical table in Takagi's office, the one that's used as a centerpiece in two separate scenes. It shows up first during Takagi's murder, and it comes back later when it's shot up by the terrorist Marco while John wiggles around underneath it. (Also, the low-hanging, this-is-patently-stupid fruit in this scenario is that Marco absolutely should've killed John several times over with his machine gun, even for how poorly he was shooting down at the table with it.)

So what makes this table so dumb? Well, it has seven right angles on it. Sections of the table are raised over others. Only two people at a time could ever face each other, and trying to look over to the front of the table ten feet down would nearly require spinning one's head atop their spine. No one would hold high-stakes, corporate business deals at a table resembling a Tetris piece.

So why don't we care? Well, it's all about style. After all, it's something of a trope that rich people own nonsensical, highly-stylized versions of everyday items. The table's ludicrous shape also helps drive up the drama when John is crawling under it trying to escape Marco.

Die Hard's weird ending

The triumphal false ending of Die Hard has John and Holly carefully descend from a pile of rubble into the parking lot to the welcome of the LAPD and the press. Paper descends from the sky as pseudo-snowfall, and it's wonderful. But the thing is, the paper ... it's all blank. Every single piece. And it's extremely obvious.

On top of that, yeah, it's an office building, but would there really be that much paper from one hole in the wall not caused by fire or an explosion? That's a little silly. Furthermore, the papers are two colors, white and green. Are the pieces fluttering by supposed to be the Bonds, as some kind of artistic statement? Why not make it all white, if you're going for snow, or all green, if you're pretending they're bonds, and you're making a weird double-ended pun of it? Doing both is the silliest of all these silly options.

However, at the end of the day, audiences don't really care because Die Hard is a Christmas movie, and all Christmas movies need a snow-backed happy ending. It's a law, somewhere. Part of the Constitution.

Gruber's terrorist chops are never clarified

In the book on which Die Hard is based, Nothing Lasts Forever, the terrorists are really terrorists. This was somewhat lampshaded in the film adaptation to keep it from getting too gritty and dark (like the book), but it also leaves a lot unresolved about Gruber. His one-liners about other terrorist sects are brilliant, but the addition of the news footage saying he was, at one point, an actual terrorist who was kicked out of the club raises a lot of odd questions.

So he was ejected from a terrorist cell ... but why? Was he too sassy? Bored? Too many incisive insults using colorful metaphors directed at his revolutionary brothers and sisters? Seeing the way he treats his cronies, this is the most natural assumption that we're led to believe, as opposed to him becoming too radical or violent. His tactical ability certainly belies a terrorist, but nothing in his personality does. His final scene literally reduces him to a thief and kidnapper, which on the scale of potential felonies and misdemeanors, ranks well below terroristic acts. Sticking to the fake terrorist bit might've been a more consistent choice. Maybe Hans was just bad at being a terrorist because he likes high London men's fashion and money. Of course, this is Alan Rickman we're talking about, and the man is so charming and so awesome that we'll look over any plot hole as long he's up on the screen.

If you want to go back and watch all of the Die Hard movies, you can find them on a variety of streaming platforms.