What The Monsters Of The Witcher Should Really Look Like

Author Andrzej Skapowski might've created Geralt of Rivia, but he didn't come up with The Witcher's cast of monsters, beasts, and creatures all on his own. Many of the foes that Geralt faces are drawn from classic mythology and regional folklore. Monsters from Skapowski's native Poland are well represented in The Witcher's lore, of course, but the series' bestiary also draws on a diverse series of sources, including English folk tales, Arabic classics, South Asian mythology, and even Grimm's fairy tales.

Of course, that doesn't mean that both Skapowski and the crew behind Netflix's The Witcher didn't put their own unique spin on things. The creatures in The Witcher might've come from myths and legends, but they don't look exactly like their traditional counterparts. They don't act quite like them either. These are the stories that inspired The Witcher's most fearsome beasts. You may not recognize them, but if you've finished The Witcher's first season — and if you haven't, beware of some major spoilers ahead – they should seem at least a little familiar.

The kikimora

Netflix's The Witcher opens with a swampy duel between Geralt of Rivia and the kikimora, a hulking spider-like creature with an unsettlingly human-esque head. While Geralt makes quick work of the beast, the kikimora ends up getting the last laugh. Despite the kikimora's ferocity, no one is willing to pay Geralt for its corpse, making all his effort futile.

While the kikimora battle makes for a great opening set piece, The Witcher's version of the creature is a very liberal take on the kikimora's legend. In Slavic mythology, a kikimora is a house spirit that sneaks into your home via your keyhole in order to deliver bad news. Once a kikimora settles in, it can also cause nightmares, sleep paralysis, and nighttime calamities like dying cattle and spoiled food. Don't ever look directly at a kikimora, either — do so, and you might die.

Instead of a multi-legged monstrosity, a kikimora typically looks like a mix between an old woman and a bird, complete with a beak and chicken legs and a headscarf wrapped around her stringy hair. Unlike Geralt, you typically don't kill them with a sword, either. Just leave some food behind the stove, where kikimory live. According to some legends, that'll do the trick.

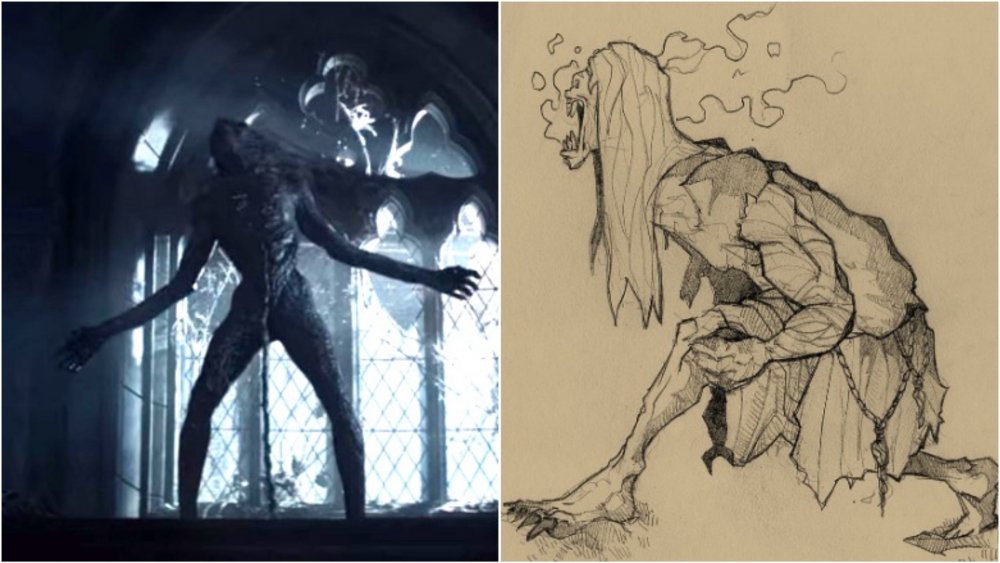

The striga

The striga is Geralt's foe in episode three of the Netflix series, "Betrayer Moon," and "The Witcher," Andrzej Skaposki's very first witcher story. In that tale, a young queen was cursed after sleeping with her brother. When the queen died, her unborn daughter continued growing until it emerged and began feeding on the local villagers. Thankfully, the curse can be lifted. Geralt simply needed to keep the striga from returning to its tomb before daybreak, which is something that's easier said than done.

On The Witcher, the striga looks like a giant humanoid monster, complete with a long, dangling umbilical cord. In Polish folklore, the strzyga is no less dangerous, but it does work a little differently. Strzygi were said to be people born with two souls, and who could be identified by their twin hearts or extra pairs of teeth. When a baby was born that people suspected was a strzyga, they were banished. Then, one of their souls died and they became monsters, often with feathers and blue or grey skin, who transformed into owls to suck the blood of their victims.

The strzyga is one of the most dangerous creatures in Polish folklore, and it's not easy to get rid of them. Some people claim that cutting off a strzyga's head and burying it far away from the body will get the job done, although burying one face-down with a sickle around its neck is said to work, too.

The sylvan

In "Four Marks," Geralt runs across Torque, a "deovel" who's been plaguing the residents of Lower Posada. Except Torque isn't actually a devil at all — he's actually a sylvan, which is also known in the world of The Witcher as a willower, a puck, or a yaksha.

"Sylvan" is just a word for something associated with woods and forests. Yakshas are South Asian spirits but tend to be friendly (although there is a type that hangs out in the wilderness and eats passerbys). The English hobgoblin Puck that seems to fit Torque best. Pouk was actually a name for the devil in the medieval era, and, similar to Torque, Puck is sometimes depicted with horns and goat legs, a la the Greek deity Pan. He's almost always short and hairy.

However, the actual Puck was a shapeshifter, and often used his abilities to play pranks on travelers. Generally, Puck is more of a troublemaker than a real villain In one tradition, a puck leads crowds through the dark and then blows out his lantern right before they walk over the side of a cliff. In another, he takes the form of a horse and gently tortures his riders. Like Torque, there's a good side to Puck, too: In exchange for cream or new clothes, Puck would help out around the house, doing the chores that regular people can't be bothered to deal with.

The djinn

The Witcher doesn't give viewers a very good look at the djinn, or genie, that binds Yennefer and Geralt's fates together. A wisp of smoke, a crack of thunder, a slight shimmer in the air. That's it.

In Arabic mythology, djinn are spirits made out of air and fire, and while they can't be seen in their natural state, they can take any form that they please — they do a whole lot more than grant wishes. In fact, the whole wish-giving element was popularized by the story of Aladdin, which wasn't added to The Arabian Nights until the 18th century, thousands of years after belief in the djinn began.

Djinns were master craftsmen who could re-fertilize barren land. They lived in two dimensions at once, and sometimes inspired poets. They can be good or evil but are usually hostile, and sometimes possessed people, necessitating an exorcism, or lured children off of known paths and lead them to their doom. Capturing a djinn lets you use its power, but that's not an easy process. If Yennefer couldn't do it? You probably can't either.

The doppler

About halfway through The Witcher's first season, the show introduces the doppler, a fearsome shapeshifter that can take the form of anyone it pleases. Traditionally, that's not quite how doppelgängers work. In folklore, doppelgängers aren't conscious, but they're bad news regardless. If you see your own doppelgänger, chances are you're about to die.

In German, doppelgänger translates to "double walker," and it's not actually a different person. It's a shadowy or ghostly reflection that looks (and sometimes acts) exactly like you, and usually serves as an omen of an upcoming tragedy. Abraham Lincoln, for example, saw a pale and sickly double of himself while looking in the mirror, leading his wife to (correctly) conclude that he wouldn't survive his second term.

There's no way to stop a doppelgänger — they're premonitions, not actual creatures — but you can identify one. Obviously, if you see someone who's your mirror image, that's a dead giveaway. If you suspect someone else might be a doppelgänger, you can look for their shadow or their reflection in the mirror. Traditionally, doppelgängers don't have either.

Duny, the hedgehog knight

The Witcher's fourth episode, "Of Banquets, Bastards and Burials," is based on the Brothers Grimm story "Hans My Hedgehog." In that story, a child named Hans is born with the legs of a human, but the body and head of a hedgehog. Years after his family casts him out, Hans runs across two lost kings in the forest. Hans offers to help them find their way, but for a price: each ruler needs to give Hans "the first thing that greets [the king] at the royal court upon his arrival home." That ends up being the princess, meaning Hans gets a beautiful wife for his trouble.

That's exactly what happens to Duny, the cursed knight in The Witcher who wins his wife via the Law of Surprise. Like Hans, Duny is half-hedgehog. Like Hans, Duny invokes the Law of Surprise after rescuing King Roegner and ends up betrothed to Roegner's unknown daughter, although Roegner's wife, Calanthe, isn't too happy about it.

Still, Hans and Duny offer in a few subtle ways. While Duny is as big as a man, Hans is hedgehog-sized. He rides a rooster like a horse, and is often mistaken for an animal. Further, Duny simply transforms into a human. Hans' shift is a lot more gruesome: not only does he physically shed his hedgehog skin, but after throwing it into the fire, his new, human skin is charred black, requiring the aid of the local healer.

The dryads

The dryads of Brokilon Forest don't mess around. Forced into hiding by humans and monsters, they fearsomely protect their land from intruders. They shoot Ciri's friend, Dara, before he can even reach the woods. They force all newcomers to drink the water of Brokilon, which kills anyone who harbors ill-will against the forest, and makes anyone who doesn't slowly forget their past.

Accordingly, The Witcher's dryads dress in armor and heavy makeup. They're imposing figures, as they should be, and they resolutely stand their ground. That's a big departure from the dryads of Greek mythology, where the creatures originated. In the original myths, dryads — or nymphs who were tied to forests or trees — were actually known for being exceptionally shy. They didn't really fight, although some of them could transform from human-like creatures into trees.

Like all nymphs, dryads were exclusively female, and are usually quite beautiful (and, according to classic Greek art, quite naked). As such, they're often the target of sexual advances, welcome or otherwise. Eurydice, wife of the famous poet and magician Orpheus, was a dryad. Two of the ten wives of Danaus, king of Libya, were dryads, too. Still, for the most part, dryads are passive figures in the Greek myths. It was up to The Witcher to give them some grit.

Renfri

At the end of "The End's Beginning," it's not clear if Renfri is really a monster. The wizard Stregobor thinks she is, since she was born under a black sun, but he's not exactly a trustworthy source. Renfri implies that she's a monster, but she's talking less about a physical mutation and more about all the people she's killed. In the end, of course, it doesn't matter. Renfri dies at Geralt's hands, and the death will haunt the witcher forever.

That's a grim ending for a character based on, of all people, Snow White. According to the short story the episode is based on, "The Lesser Evil," Stregobor first caught wind of Renfri's possible mutations when her stepmother saw a vision in a mirror depicting Renfri committing murder. At Stregobor's request, the queen sent Renfri into the woods to be killed, but the man raped and robbed her instead. Renfri killed the man and moved in with a group of gnomes, who helped her establish a gang of criminals. The queen sent assassins after Renfri and almost killed her with a poisoned apple, but the girl survived.

Of course, the original Snow White gets pretty dark, too — as punishment, the prince in Snow White forces the evil queen to dance in red-hot slippers until she dies, so at least Sapkowski comes by the darkness honestly.

The dragon

In "Rare Species," Geralt and Jaskier join a group of warriors who are competing to see who can kill a dragon first. Not only is the hunt that ensues is full of twists and turns, but it's a big part of The Witcher's behind-the-scenes history: The story that the episode is based on, "The Bounds of Reason," is an adaptation of the Polish folktale that inspired Skapkowski to create Geralt in the first place.

The story of the Wawel Dragon dates back to the 13th century, and while it takes many forms, some elements are always the same. There's always a king whose subjects are terrorized by a man-eating, cattle-devouring dragon. There are always brave knights who try to conquer the dragon in hopes of winning the princess' hand. They always fail. Finally, there's always a hero, usually depicted as a cobbler, who decides to use the dragon's own appetite against him. The cobbler fills a sheepskin with hay and sulfur, then waits for the dragon to eat it. That makes the dragon so thirsty that it drinks water until it literally explodes.

It's one of Poland's most beloved stories — there's even a statue commemorating the dragon in Krakow — but Sapkowski thought it was ridiculous. You wouldn't call a cobbler to kill a dragon, he figured. You'd call a professional. And so, the author invented a fictional monster hunter, and lo and behold, Geralt of Rivia was born.

The ghouls

Neither "Much More" nor the story its based on, "Something More," name the skeletal creatures that give Geralt his nasty wound, but fans tend to call them ghouls. In Arabic folklore, a ghoul is a creature that lives in cemeteries and feast on human flesh. In some tellings, ghouls also lurked in the desert, where they'd take the forms of beautiful women order to lure men to their deaths. The only defense? Kill it in a single blow. If you have to attack a second time, it'll come back to life.

However, there's another option. CD Projekt Red, which made The Witcher video games, used the monsters in "Something More" as the basis for the nekker, a creature that actually takes its name from a completely different myth. In Dutch tales, a nikker (or nix, or neck) is a demon that lives in the water and lures in victims by pretending to be a drowning child. Once it has its hands on its prey, however, the nikker would suck their blood and store their soul in a jar.

Some tales say that nix are shapeshifters. Others claim that they have black skin and red hair and eyes, or green or blue hair. Calling out a nikker's name will kill it for good, although silver will do the job too, or you can keep it separated from water for a while. Once it dries out, it's as good as gone.