Opening Scenes That Were The Best Part Of The Movie

As the saying goes, you only get one chance to make a first impression. That's almost doubly true when it comes to movies, where the first five minutes have the chance to turn an unfriendly audience into deeply invested fans. After all, it's the audience's first glimpse at the themes, characters, and even possibly the spectacle of the movie they're about to see. To put it simply, the opening scene of a movie might be the most important scene in the movie.

Unfortunately, sometimes movies go a bit overboard in the opening, showcasing a world or creating ideas that the rest of the film just can't live up to. And while the rest of the movie might be pretty awesome — or it might absolutely suck — it never quite compares to those first few minutes that promised so much. From superhero flicks and spy thrillers to horror films and modern-day classics, here are the opening scenes that were the best part of the movie.

Baby Driver hits top speed immediately

From Shaun of the Dead to Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, the one thing you can always count on Edgar Wright to deliver is an incredible action set piece. And Wright decided to start Baby Driver with a jaw-dropping, six-minute opening scene that showcases Baby's (Ansel Elgort) love of music, his exceptional driving skills, and how far the cops are willing to go to catch this crew of bank robbers. There's a ton of detailed character work and subtle worldbuilding that's going into the first scene, but it's also incredibly fun to watch. The timing of Baby's playing in the car synced up to the Jon Spencer Blues Explosion is a masterclass in setting up and immediately subverting expectations. It turns an incredibly tense set piece into a joyous encapsulation of how great it feels to listen to music in the car.

Hardcore fans of Baby Driver could argue that following scene, an impressive tracking shot following Baby getting coffee set to Bob & Earl's "Harlem Shuffle" is better, but while that long shot is impressive, it's ultimately just in conversation with the opening scene. In fact, pretty much the entire movie uses the opening scene — in which Baby is at his most comfortable, morally and musically — to contrast against every other moment. In other words, the first few minutes, besides being exciting and fun to watch in their own right, give the entire movie a working engine to run on.

The opening of Casino Royale made Daniel Crag a star

It might be hard to remember now that we're over a decade into Daniel Craig as James Bond, but when he was first cast as the suave super spy for 2006's Casino Royale, there were plenty of fans who hated the idea. These fans argued that Craig was too blue-collar and even too blond to play the legendary role. Whether they liked it or not, however, the Bond series was in desperate need of some new blood after 2002's Die Another Day was savaged by critics and audiences alike (even if it did just fine in the box office).

With so much pressure to showcase a new James Bond for a new generation, the opening scene of Casino Royale became even more important. Traditionally, the opening scenes of Bond movies had been high-budget, action-packed affairs filled with explosions, mysteries, and Bond at his most competent. Casino Royale immediately subverted audience expectations by presenting two very different and very important kills that would go on to define Craig's Bond. In one, Bond confronts a crooked MI6 section chief in a twisted game of cat-and-mouse, shot with a cool black-and-white filter. In the other, Bond drowns a man in a bathroom sink in the world's dingiest bathroom, shot with shaky camerawork and a garish filter. It immediately presents Craig as capable of the kind of dry coolness that his predecessors had, while also showing that his version of Bond is more than willing to get dirty in a protracted and violent bathroom fight scene. As cool as the later parkour set piece might be, this is when Daniel Craig truly became James Bond.

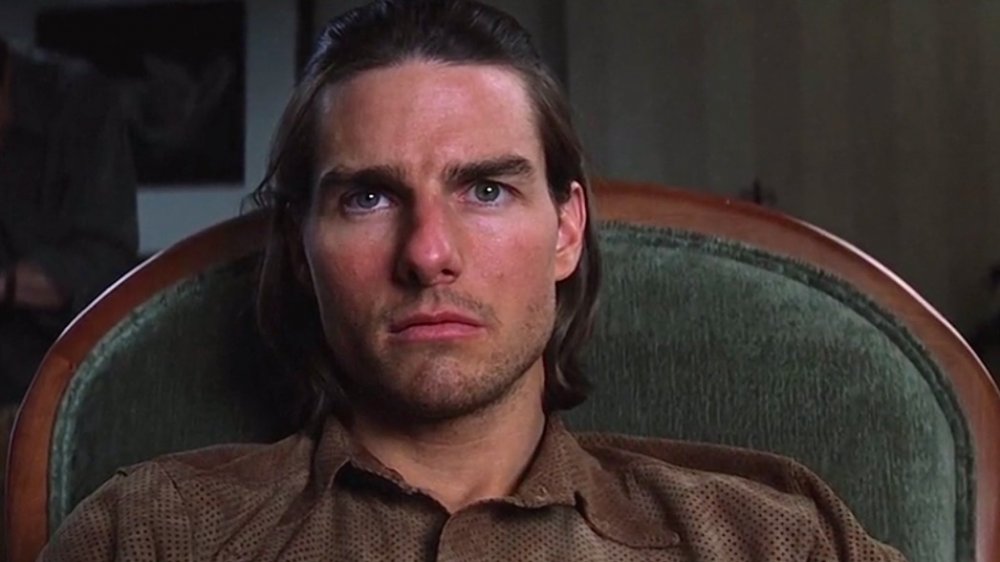

Magnolia's weird opening starts things off strong

Even for a director as utterly unique as Paul Thomas Anderson, Magnolia is a strange movie. It follows the lives of half a dozen different characters, any one of which could, and probably should, anchor their own film. It's a movie about Los Angeles that takes place mostly in the valley, and the closest it ever gets to the glitz and glamour of Hollywood showbiz is a child's version of Jeopardy! and a pick-up artist plying his gleefully misogynistic ideas as his ticket to "fame." It features an infamous scene partway through the film in which every character sings a bar from Aimee Mann's "Wise Up." Fans and haters alike can agree that it's a weird movie.

That said, the opening scene seems to showcase a movie just as weird but more in line with Anderson's expected level of exacting control. It features Ricky Jay narrating three stories, all of which seem to be connected by their reliance on bizarre coincidences. Jay's crisp narration, honed from a life as a legendary magician, makes the tales feel even stranger than they actually are. Even if you don't know Jay's past vocation, it feels like you're watching a magic trick, waiting for the ball that's disappeared to pop back into the magician's hand. Anderson's control is at its peak in this opening sequence, as razor sharp and tight as anything in Boogie Nights or Phantom Thread. Unfortunately, the rest of the movie gets looser and shaggier from there. The film has its fans, but for anyone who delights in Anderson's meticulous style, it doesn't get any better than the opening scene.

Hancock showed a superhero at his lowest

Hancock presented audiences with a singularly powerful high concept: What if Superman was an alcoholic good-for-nothing? It's a concept that's only become more pertinent as the superhero genre has widened from being a small slice of the pie to one of the few genres that consistently make money at the box office. In any case, 2008's Hancock makes the movie's original high concept clear within minutes. Audiences meet Hancock passed out on a city park bench, pushed into action to stop runaway bank robbers by a little boy who seems frustrated to even have to tell the superhero about a crime.

Hancock flies after the bank robbers, swaying in the wind like a drunk minutes after last call, and when he finally stops the robbers, it's only after causing millions of dollars of damage in Los Angeles. At a time when the Marvel Cinematic Universe was just ramping up with the release of Iron Man in the same year, Hancock could've been a gleefully nihilistic and biting satire of superhero films. At the very least, it could've presented the sort of juvenile thrills and half-baked ideas of other Superman-pastiches like Brightburn. Instead, this version of Hancock — drunk, lazy, and annoyed at the demands people make of his heroism — is nearly instantaneously replaced with a good-hearted guy just doing his best after years of tragedy. The opening scene promises a more vicious (or at least more fun) look at superhero action, but the film itself provides the same redemption and superhero origin story that every other film in the genre offers.

The opening of X-Men Origins: Wolverine was the best part of the movie, bub

One of the most interesting things about Wolverine is that his healing factor has given him an extended life span. And that immediately places him in the lineage of worn-down anti-heroes like Philip Marlowe, characters who find danger and intrigue around every corner but don't enjoy any of it. That particular quality of Wolverine's was hinted at in the X-Men movies before finally getting textual weight in 2017's Logan. Before that, all X-Men fans had to enjoy if they wanted to imagine how much Wolverine's decades had worn on him was the opening scene and credits of X-Men Origins: Wolverine.

While the scene starts with a relatively toothless origin story for Hugh Jackman's Logan, it kicks in to high gear with a montage of Logan and his brother, Creed (Liev Schreiber), fighting through major historical wars, from the Civil War to Vietnam. The rapid-fire scenes of bloodshed, only distinct in how the characters are dressed, immediately makes it clear that Logan is looking for a war, rather than a cause. It underlines his guilt at his father's death in a way that's far cleaner and simpler than a child screaming in a parody of Jackman's acting. Unfortunately, the clear visual and thematic synthesis of those opening credits eventually lead to a scene where Deadpool shoots optic blasts and has katana arms. So yeah, it doesn't get any better than those first eight minutes.

Blade and the blood rave made the '90s cool

Blade is a phenomenal movie for many reasons. There's Donal Logue's absurdly lovable and eminently hatable vampire henchman, Quinn. There's the exceptional fight choreography that, more often than not, just wants to show how physically talented Wesley Snipes is as a performer. And there's Snipes himself, so absolutely, undeniably cool in the roll as the half-vampire vampire hunter that the comic character itself was basically reshaped around Snipes' performance. All of those qualities are immediately shown off in the best way in Blade's opening scene, along with plenty of other wonderful details.

As Traci Lords' vampire character drags an unwitting victim to a rave, she barely even bothers to hide her disdain. Even when the soon-to-be victim sees a human body in a bag getting carted through a slaughter house, he's immediately distracted by Lords kissing him dispassionately. It's become rote to her, and even the other vampires barely bother trying to hide their true nature from him, especially once blood starts pouring down from the sprinklers. It's absurd '90s excess, casting vampires as the ultimate bored rich kids. Then Blade walks into the room. The music cuts, the vampires react like embarrassed children, and Blade, covered in black leather, proceeds to slaughter the entire crowd of vampires. It's an incredible opening scene, so good that the rest of the movie almost pales in comparison, like Deacon Frost wearing sunblock.

Scream will make you scream in the first five minutes

Meta-horror has become about as mainstream as regular horror these days, but that wasn't the case when Wes Craven terrified audiences with Scream in 1996. Before The Cabin in the Woods or Detention surprised audiences with the idea that characters in a horror movie could've seen a horror movie, Scream showed that even making the "right" decision in a horror film wasn't guaranteed to save your life.

The opening scene of Scream is a masterclass in subverting audience expectations. It starts with Casey (played by Drew Barrymore, by far the most well-known member of the cast at the time) answering progressively creepier questions from a mysterious caller over the phone. The caller, Ghostface, quizzes Casey on horror movies with her boyfriend's life on the line if she gets a question wrong. When she inevitably does, Ghostface kills her boyfriend, and then, in a horrifying sequence immediately after, murders Casey herself.

Beyond the shock value of immediately killing off Barrymore, the scene is absolutely brilliant in how it slowly builds tension around whether Casey, clearly aware of the horror movie tropes, will be able to use that knowledge to survive. Her failure to do so only sets Scream apart as a slasher film unlike any that you've ever seen, showcasing a potential that the actual movie never quite matches up to. Scream isn't a bad movie by any stretch, but it never reaches the high of that opening scene for the rest of its runtime.

The Brood's opening gets things going in a disturbing direction

David Cronenberg's The Brood is, like all Cronenberg films, deeply upsetting. In the case of The Brood, a lot of that horror comes from the eponymous brood and the movie's subtext that familial trauma is basically a bomb just waiting to explode on the next generation. It gets even more upsetting when you read interviews with Cronenberg himself where he makes clear that the film, which follows a man trying to keep his daughter safe from her increasingly unhinged mother, was written after Cronenberg's own divorce. In his own words, "The Brood is my version of Kramer vs. Kramer, but more realistic."

There's a lot to unpack there. There's also a lot to unpack in the opening scene, which features a public therapy session between the creepy Dr. Raglan and Michael. Dr. Raglan goads Michael, taunting him like a disapproving father, while Michael sobs and the audience watches quietly. When Michael finally explodes in anger, ripping off his shirt, his flesh is covered with strange boils or sores. It's immediately clear that whatever therapy Dr. Raglan is interested in, it doesn't seem to be beneficial for the patients. The movie gets wilder from there, especially once Cronenberg's trademark penchant for body horror and violence emerge, but the film is never as strange or enticing as that opening scene.

Reservoir Dogs takes care of any reservations you might have

It's one of the most famous opening scenes of '90s cinema, and for good reason. Pulp Fiction might've made Quentin Tarantino a star, but Reservoir Dogs is what made Tarantino one to watch in the first place. A heist movie where you barely see the heist, Reservoir Dogs is mostly about the characters involved in the robbery, their specific dialogue covering for any lack of action in the script. The opening scene epitomizes this idea, with a long, drawn-out discussion about the meaning of Madonna's "Like a Virgin" that turns into a conversation about the value of tipping at restaurants. For the record, you should always tip, because that's the right thing to do, but one of the criminals, Mr. Pink (Steve Buscemi), balks at the idea.

Buried under the conversations about the meaning of pop culture — a quality that would follow Tarantino for the rest of his career — the scene's seeming banality masks a complicated power dynamic between the criminals that's only obvious after seeing the rest of the movie. Even before you have a good sense of each character and the role that they'll play in the following hour and a half, they act true to their nature. Mr. Pink's only in it for himself, and he gets away with the money. Mr. Orange rats out Mr. Pink as the non-tipper, and lo and behold, he's the undercover cop. What seems like an engrossing scene about nothing still manages to sneak in some character work with some of Tarantino's subtlest writing.

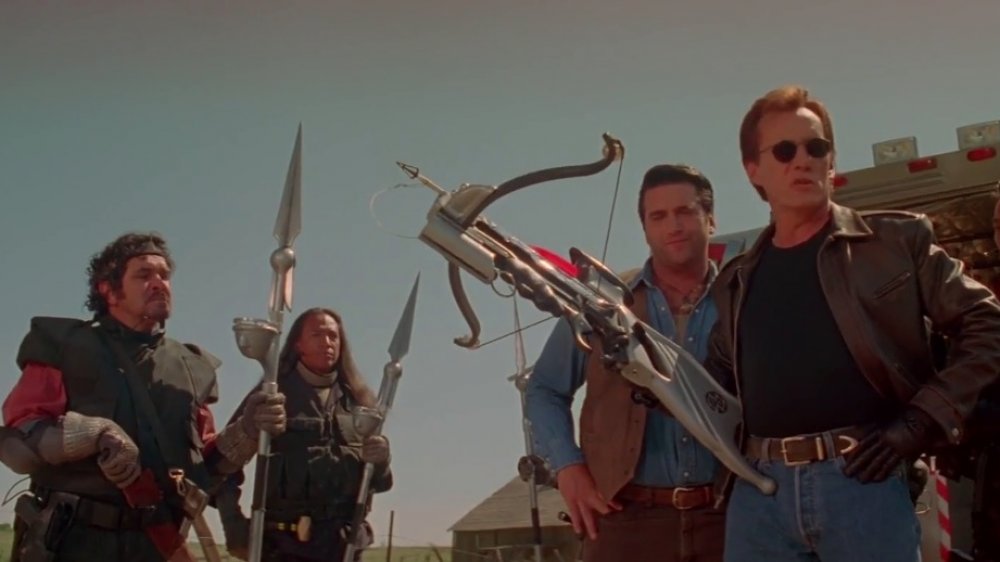

The opening of Vampires is the best part of this horror flick

Vampires isn't likely to be on anyone's list of the best John Carpenter movies, but the mostly-middling film has a couple of excellent qualities. One is Twin Peak's Sheryl Lee, gamely putting in far more work than the film really deserves. The other is a great opening scene. As a van and jeep drive up to a farm house, a priest and a cavalcade of well-armed men get out. They're at the house to clean out a nest of vampires, and they treat the whole affair with as much fear and concern as any type of exterminator treats a new job. It's not so much a tense scene as it is an exceptionally blue-collar one.

Every vampire movie since Nosferatu has struggled to get past the monster's recognition in pop culture. From Blade to Twilight, basically every vampire ever has had to stop the action and establish what makes this specific movie's version of a vampire different from all the other versions. Vampires eventually falls into that trap, too, but the opening scene says leagues more about this universe's conception of the monster than any number of expository monologues. Like Carpenter at its best, it showcases themes and worldbuilding with visuals, rather than getting bogged down with complicated mythology. It's just a shame the rest of the movie can't live up to that promise.

Police Story's opening is action-packed

Jackie Chan's filmography is absolutely packed, and out of all those credits, Police Story is one of his very best films. The biggest reason behind that? Well, it's Jackie Chan himself, who writes, directs, stars in, and even performs the theme song of the film. When you sit down to watch Police Story, you're there for Chan, and if there's a story to enjoy on top of that, that's a bonus.

But at first, the opening scene of Police Story seems almost languid, jumping between explanations of criminal histories as a sting to catch those same criminals is being set up. Then things go off the rails. The sting gets interrupted, there's a shoot-out, and then in a scene that would make Michael Bay weep in envy, two cars drive through an entire shantytown on a hill. That escalates to Jackie Chan chasing down a bus on foot, at one point hanging on to the outside of a bus window with an umbrella handle. It's glorious, ridiculous, and nearly 20 minutes of escalating action without a moment to breathe. Leave it to Jackie Chan to realize that the problem with most action movies is that they don't have enough action or enough Jackie Chan.

Putney Swope puts it all on the table immediately

Robert Downey Sr. (father to Robert Downey Jr.) made plenty of great films in his time as a director, but 1969's Putney Swope might be his most successful, at least according to him. It's the story of a token black man on a board of advertisers who becomes the head of the company and immediately starts instituting wild changes. The movie ranks up there with Mel Brooks' films for sheer jokes-per-minute, but while the characters can sometimes hit too broadly in the back half of the film, the opening scene is a thing of beauty.

A tracking shot from a helicopter leads to a man who's holding a chained briefcase and wearing a jean jacket covered in fascist symbols with "MENSA member" on the back. The man heads to an advertising agency board room where he proceeds to tell the assembled men that "beer is for men who doubt their masculinity" before leaving the room. One executive reveals that the brief exchange cost $28,000, and that they "got off easy" for that price. From there, it quickly devolves into petty squabbles, pointless stories, and arguments over who actually deserves their seat at the table. In other words, it's a standard advertising meeting. Then a body keels over, and the energy of the scene gets as manic and hilarious as an Eric Andre bit. It's no wonder that Putney Swope gets a bit broad for the rest of its runtime. This scene alone has as much energy as a whole season of SNL skits.