The Most Successful Western Ever

Westerns are the cinematic equivalent of the American Standard: perennially popular, endemic to American culture, and a living historical symbol of its nation's comparably young identity. They are latter-day fantasy, where the knight errant is replaced by the silhouette of Clint Eastwood, and the rolling hills of Europe are exchanged for the buttes and cacti of the American West, and even today its legacy is felt, referenced, and invoked in films that have nothing to do with the desert, or 19th-century Americans, or prospecting. There is nowhere on Earth untouched by Western film culture, and hundreds of films are encapsulated by the single-word description.

It is impossible, then, to name just one film as the most successful Western of all time. There are many qualifications to consider: box office revenue, critical acclaim, public recognition, overall societal impact. The last is the most nebulous, but also might be the most important; Westerns are so numerous and so popular that the cream rising to the top are their own more complicated icebergs of context to be mined. All of this, of course, is drastically separated from a favorite, which is entirely up to taste based on totally different metrics, like director or lead actor. So: using all of these criteria, what are the most successful Westerns, so far as this is able to be quantified?

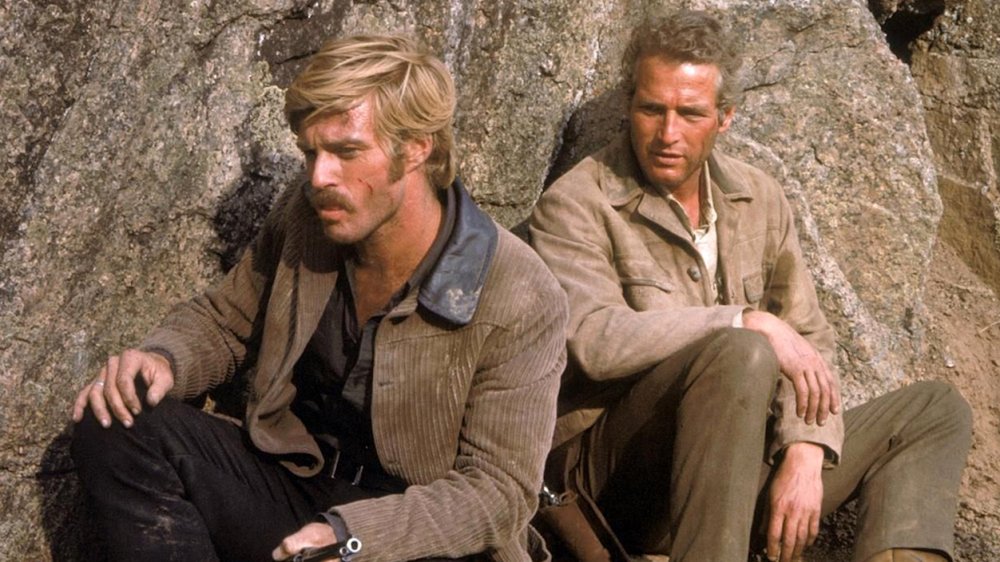

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, highest-grossing Western ever

The Western as a cinematic art form is over a century old, and reached a popularity apex in the '40s and '50s, so of course, any statements of revenue need to be adjusted for inflation to be fair. Even middling financial performances today are capable of outclassing even the highest-revenue films of the golden Hollywood era; mo' people, mo' movies, mo' money. Fortunately, Newsday spared us having to do the math: the winner for objective financial success is 1969's Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.

According to today's numbers, the classic film (and multiple Academy Award-winner) generated more than half a billion dollars' worth of revenue. It was the box office hit of 1969, too, outstripping several other Western-genre films that year by magnitudes to make a contemporary $100 million within the calendar year. It featured perhaps the biggest star in the world in Paul Newman (and his co-star, Robert Redford, would soon have a claim to that title), and it broke another contemporary financial record before it was ever made: 20th Century Fox paid $400,000 just for the privilege to produce its screenplay, which was a price never before paid for a script. Good thing that all worked out.

Dances with Wolves won the most Oscars of any Western

Many Westerns have won Oscars over the past century; Cimarron, High Noon, the aforementioned Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. At the 1991 Oscars ceremony, however, Dances With Wolves arrived and swept the slate, taking home seven of the twelve categories it was nominated for: Best Picture, Director, Adapted Screenplay, Original Score, Film Editing, Cinematography, and Sound, making it the champion for most Oscars awarded a single Western film.

It sought to be something different and new in popular cinema: a Western willing to put aside high action and individual moral murkiness to assess the greater, mixed legacy of Americans' conquest of the western half of the nation and at least partially frame the story around the subjugation of the Native population that had called it home for millennia before Europeans. Of course, it is also Oscar bait in the classic '90s sense: huge in scale, exacting in detail, a writer-director-actor vehicle for Kevin Costner at the pinnacle of his fame. It was all but destined to sweep its awards slate in 1991, and it's difficult to imagine a modern entry to the Western genre — these days more interested in small, personal stories like your remakes of True Grit or remixes like The Hateful Eight — to be so willing to aim for the same size and grandeur.

The Treasure of the Sierra Madre earned the best reviews of any Western

Thanks to the current era's obsession with algorithmizing literally anything no matter when it occurred, we can point to the best critical success of the Western genre: The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. This 1948 classic was obliged to garner glowing reviews due to the inclusion of Humphrey Bogart in the starring role alone, but it has stood the test of time, reigning at a perfect 100% on Rotten Tomatoes with 46 reviews scattered across the half-century-plus since its theatrical release. It's set in the '20s, well past the epoch of horse-driven carriages, gunslingers, and the time when the West was empty, but it has all the hallmarks nonetheless: outlaws, gold prospecting, wild and barren landscapes where lone wolves save two-bit dusty frontier towns and become beloved.

Sierra Madre features no white hats or even gray ones to save the day: it's a parable about greed, and its targets are the subject of accurate karmic suffering. The great Roger Ebert described it best in his own glowing review when he revisited it on the then-still-new medium of DVD in 2004: "There is a pitiless stark realism in these scenes that brings the movie to honesty and truth. Leading up to them is a down-market Shakespearean soliloquy when Dobbs thinks he is a murderer and says, 'Conscience. What a thing! If you believe you got a conscience, it'll pester you to death. But if you don't believe you got one, what could it do to ya?' He finds out."

The films of Kurosawa are among the most culturally significant ever made

Cultural significance is a slippery term. The Western genre certainly defines American culture in such a profound way that any iconography related to a cowboy can be utilized to represent An American in media, and be instantly understandable, no matter the language. All of the ten-to-twenty films that most often populate "Best Western Movie" listicles also each, in their own way, have left indelible prints on our lives — but a special shout-out should be given to the particular selections borne of a unique cross-cultural exchange in the years post-WWII.

Yes, indeed, we do mean the samurai-slash-western-film thematic cross-pollination most famously conceptualized by Akira Kurosawa. Any true die-hard Western fan will include Yojimbo and Seven Samurai as entries into the Western pantheon along with its western-hemisphere remakes that are individuals in their own right: Fistful of Dollars and The Magnificent Seven. Is there a greater victory for cultural impact as inspiring art between nations that, at the time, had been at very bitter war with each other less than a decade before?

Westerns, Spaghetti-flavor or otherwise, had been popular media well before WWII; Kurosawa had seen those films, delighted in them and, after Japan surrendered and it was permissible to indulge in American cultural diversions once again, made masterpiece after masterpiece using those Western tropes. Those masterpieces, in turn, were adapted through the eyes of an Italian and an American to create works of equal quality and identity. That's three separate nations, all with wildly different traditions, food, and religious convictions, coming together to provide artistic filters through which timeless art is made. This is the ideal of towards which humanity should reach in hopes of sustaining peace on Earth.