The Ending Of The Platform Explained

When the Netflix original film "The Platform" ("El hoyo" in its native Spanish) dropped in February 2020, it quickly started freaking everyone out for its unique dystopian horror setting and the prescient symbolism at the core of the narrative. At first glance, the film — which has since become one of Netflix's most popular original movies of all time — appears to be a story of individual greed and the struggle to survive, but as the story reaches its haunting conclusion, it becomes clear that there's something deeper going on.

At the outset of "The Platform," we're introduced to Iván Massagué's Goreng, a new inmate in a vertical prison. At the top, a team of chefs prepare a lavish feast big enough to feed everyone in the hundreds of cells below, and each day, the titular platform containing the food is lowered. The platform stops at each cell for two minutes, and the two prisoners in that cell can eat as much or as little as they want. Of course, those at the top get their fill, while those at the bottom are left with nothing and end up starving. The catch is that the prisoners are assigned a new cell each month, rearranging the pecking order in relation to the platform.

The ambiguous ending of "The Platform" and the film's metaphorical nature throughout have left many viewers trying to figure out what it all means. Let's run through the symbolism of the movie and what message the filmmakers wanted us to take away from the final moments.

What exactly is the purpose of the prison in The Platform?

We get bits of details about what the purpose of the prison is throughout — and there are theories about its administration that could change "The Platform" forever — but it's not until Goreng meets Imoguiri (Antonia San Juan), who worked for the prison herself before becoming an inmate, that we get a more concrete idea.

Imoguiri tells Goreng that the administration prefers to refer to the pit-like prison as a Vertical Self-Management Center (VSC). She explains that in order for the food to reach all the way down to the lowest levels there needs to be a "spontaneous sense of solidarity" — meaning everyone, without communicating to one another, only takes as much as they need. She seems to imply that the whole purpose of the prison is to create a system in which people can learn to foster this spontaneous sense of solidarity.

However, Goreng proposes a more sinister interpretation: "If that solidarity emerged, they'd know to prevent it happening on the outside." If we are to take Goreng's interpretation of the prison, then it's a small-scale model of a harsh capitalist system that the ruling class is using to test the responses of the proletariat. It's a tool for the rulers, not society as a whole.

What do each of the characters in The Platform represent?

Most of the main characters we meet in "The Platform" represent archetypes or ideas larger than themselves. For instance, Goreng, who volunteers to enter the pit in order to obtain a college diploma, represents an idealist intellectual. At the beginning of the film, he shames the greed of those who take more than their share when they have the opportunity, but doesn't understand why they do it, as he has yet to spend a month at the bottom of the pit.

Similarly, Imoguiri represents the willfully ignorant bureaucrats upon which a system like the VSC rely in order to function. When Imoguiri enters the pit, it's revealed that she's mostly in the dark as to what actually happens in there. Like Goreng, she attempts to convince the prisoners below her to ration their food, but they don't listen to her pleas.

Perhaps the most enigmatic character in "The Platform" — who's left fans scratching their heads — is Miharu (Alexandra Masangkay), a mute woman who rides the platform each month in search of her young child. Miharu is disdained by the fellow prisoners and is often attacked. Even Imoguiri derides her struggle, claiming that her search for her child is a lie because nobody under 16 is allowed in the pit. Miharu represents those who suffer on the periphery of society, whose stories we don't want to believe because they sound so cruel that we can't imagine that we live in the same system — for instance, people experiencing homelessness or other forms of extreme poverty.

The meaning behind the the ending of The Platform

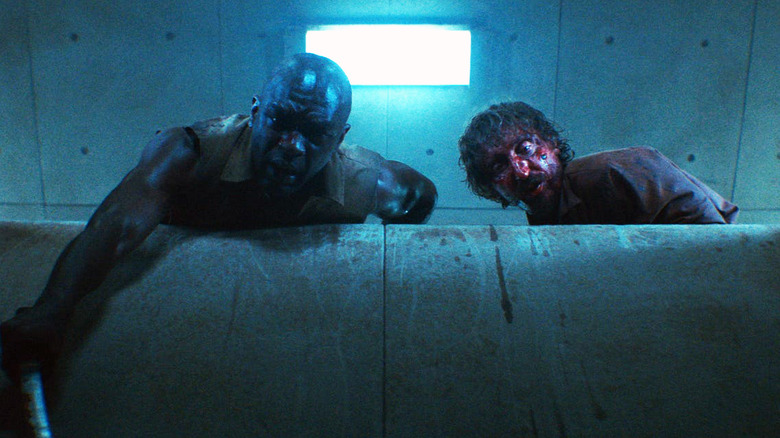

At the end of the film, we learn that Miharu's child is real, and has been living at the very bottom of the pit. Goreng arrives there after riding the platform down with a weapon, enforcing the rationing of the food by beating and killing anyone who tries to take more than their share. His plan is to return back to the top level with an uneaten dessert, a panna cotta, as a symbol that the prisoners have learned how to work together to survive in such a way.

However, after finding the child, Goreng realizes that that isn't the message he needs to send. The discovery of Miharu's child is confirmation of the most important component of the VSC experiment: those in power set the rules, but they clearly don't follow them themselves. Although they've assured everyone they would never do something as cruel as allow a child into such a horrendous existence, that was a lie.

The conclusion of "The Platform" sees Goreng sending the child back up on the platform as a message to the chefs at the top, who are presumably in a similar state of ignorance as Imoguiri. Instead of proving to them that the prisoners can adapt to the system, he wants to show them that the system itself is unspeakably and unfathomably cruel, and those operating it cannot be trusted.

What is the message of the panna cotta?

Before choosing to send the girl up to the top, Goreng and Baharat (Emilio Buale) decide that the panna cotta should serve as a symbol, to show those in administration how the prison is capable of self-control. It's a message that they can, in fact, exercise restraint and even send something delicious back. However, as you might imagine, there's more to the panna cotta than meets the eye.

Earlier in the film, there's a scene where a chef freaks out over there being a hair in the panna cotta and how they must redo it. It seems ridiculous because it's not like starving prisoners would care if there's a hair in their dessert, but it represents the disconnect between those overseeing the prison and those living in it. They care more about their precious dessert being perfect than the fact that they work for a system that fosters murder and cannibalism. Additionally, Goreng and Baharat keep the panna cotta on Level 333 to share with the child. In contrast to what we've seen previously, the room doesn't become extremely hot or cold. It begs the question as to whether this is just part of Goreng's hallucination as he is dying.

Taking the film for what it is, the child is a more powerful symbol than the panna cotta. This is because the child forces the upper class to see the impact of the system they created, whereas the panna cotta is their own creation, something they'd probably be fine discarding and ignoring even if it made it back up.

The Platform director Galder Gaztelu-Urrutia explains the film's ending

"The Platform" director Galder Gaztelu-Urrutia spoke with Digital Spy in September 2019 following the film's world premiere, and shed some light on the ambiguous ending. For Gaztelu-Urrutia, the way "The Platform" wraps up demonstrates "the failings of different ideologies."

"We certainly do think that there has to be a better distribution of wealth, but the film is not strictly about capitalism," explained Gaztelu-Urrutia. "There may be a criticism of capitalism from the beginning, but we do show that as soon as Goreng and Baharat try out socialism to convince the other prisoners to willingly share their food, they end up killing half of the people they set out to help."

In the end, Gaztelu-Urrutia aimed for the conclusion of "The Platform" to be "open to interpretation, whether the plan worked and the higher-ups even care about the people in the pit." An alternate ending of was even filmed, though it was obviously scrapped in favor of the one viewers saw. "We actually did film a different ending of the girl arriving at the first level, but we took it out of the movie," said Gaztelu-Urrutia. "I'll leave what happens to your imagination."

What is Goreng's fate in The Platform?

As Goreng gets to the final level, he's badly injured but initially believes he must be a bearer to the message (the message being the child). However, he hallucinates Trimagasi (Zorion Eguileor) telling him that the message requires no bearer, so he gets off the table so that it may ascend to the very top of the prison, showing how the system is so inherently flawed that it would allow a child to suffer. It appears to be intentionally ambiguous as to whether Goreng lives or dies, but director Galder Gaztelu-Urrutia has explained the more straightforward answer. Goreng does, in fact, die.

Gaztelu-Urrutia elaborated to Digital Spy his interpretation of what Goreng has to do. "To me, that lowest level doesn't exist," he states. "Goreng is dead before he arrives, and that's just his interpretation of what he felt he had to do." It forces the audience to question whether it's even possible to dismantle a corrupt system.

In this way, Goreng represents the older generations needing to sacrifice themselves so that the younger ones can build a better future. Goreng has sowed seeds for trees he'll never see, giving his life in the process.

What is the symbolism of there being 333 levels?

It's not quite clear throughout much of "The Platform" as to how many levels exist. At first, it's believed there are roughly 200, only for it to grow to at least 250 at another point. It's not until the ending of "The Platform" that we learn there are actually 333 levels. It seems like an odd number to pick, but there's likely some symbolism to scour through.

For starters, there are two prisoners per level, meaning there would be 666 prisoners total. 666 is naturally the "number of the Beast," implying the prison functions as hell, where the prisoners are tortured ad nauseam. However, 333 is a significant angel number in and of itself, with cosmic numerologist Jenn King telling USA Today what 333 specifically represents. "It's a really nice reminder that you have influence, that you have agency, that you have power, and whatever you direct your energy, your thoughts, your emotions, your love into is going to grow," she claimed.

There's no greater agency than trying to dismantle a corrupt system. Goreng is merely one man, but he takes it upon himself to get a symbol across to the perpetrators of such a system at the cost of his own life. Goreng may not learn if his actions bore any fruit, but ideally, his influence lives on with the young girl.

What happened to Imoguiri's dog?

Movies can often kill as many people as they want without many viewers batting an eye. But if a dog is put in harm's way, it adds a whole new level of tragedy. Given how dark "The Platform" is, it's understandable if audiences immediately become nervous upon realizing Imoguiri brought a dog in with her. Given the dog-eat-dog nature of the prison, it's perhaps no surprise to see the dog meet an untimely end after Miharu kills him. But why exactly does Miharu do that?

The simplest explanation is revenge. Imoguiri works for the administration prior to entering the prison, so Miharu's act of violence could function as a way to get back at said administration. Killing the dog could also be seen as an act of defiance. Imoguiri selfishly brings the dog into the prison, allowing it to eat food on half the days while she eats on the other half. Even with that system, a dog is still partaking in meals meant for human beings, exemplifying Imoguiri's complete lack of self-awareness concerning the conditions the prisoners find themselves in.

As with most things in "The Platform," killing the dog likely carries symbolism with it. The dog's name is Ramses II, a famous Egyptian pharaoh. Miharu killing Ramses II could symbolize the oncoming revolt with the death of something named after royalty. It may have thematic weight, but it's tough to watch for dog lovers all the same.

What does Don Quixote represent?

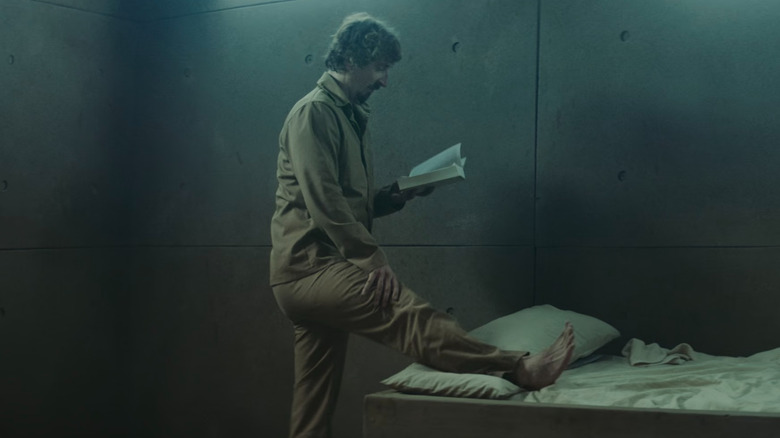

Everyone can bring one item with them into the prison. Trimagasi brings a knife for obvious reasons. Baharat brings a rope. And Goreng faces derision because he decides to bring a book, specifically "Don Quixote." In his naive view upon first entering the prison, he believes he'll only be there for six months and upon release will get a college degree. So in the meantime, he'll catch up on some classic literature. For anyone who's read "Don Quixote," the parallels should be fairly clear.

Don Quixote exemplifies naivety. He wants to become a knight and seek out adventure in the name of reviving chivalry. However, he's misguided throughout much of the story, famously battling windmills at one point because he thinks they're giants. An untold truth of Goreng in "The Platform" is that he essentially functions as a metaphor, and in this case, he's a modern-day Don Quixote himself. Goreng is similarly naive at the beginning of this story. As time goes on and Goreng is forced to make difficult decisions, he no longer has those more simplistic beliefs.

One could even argue that Goreng sets out on his own quixotic quest to dismantle the prison's system. The prison represents how the upper classes always want to take more than what they need, leaving nothing for the majority of society. To break this down essentially requires the dismantling of capitalism, which may be as foolhardy as fighting windmills.

Does the child survive the ending of The Platform?

Since there was the intention to include a scene showing the child making it to the top, we can likely infer that even if Goreng hallucinates some of the ending, the kid makes it out okay. Without that final scene, the ending of "The Platform" is made even more ambiguous, with audiences left to wonder whether the child survived and if her ascension even made a difference in creating a better system.

Regardless of the child's literal fate, she's meant to represent hope for the future as well as the pain and struggle the younger generations are going through now in the real world. Goreng finds the child on the very last level. Absolutely no food makes it that far down, part of the central critique "The Platform" offers toward capitalistic society. It's stated how the titular platform has enough food for everyone, provided they only eat a small, manageable amount. The problem is that some people consume so much, beyond their means, that there's nothing left for those on the bottom.

In essence, the older generations have already consumed so much that there's nothing left for the younger ones. It's possible for said child to break this system, but it's going to require radical action.

How does The Platform tie into The Platform 2?

Rewatching "The Platform" can be an entirely different experience when you understand all of the symbolism and metaphors. To an extent, a sequel almost seems superfluous, but that's exactly what the world got in October 2024 with "The Platform 2." The film focuses on two new individuals — Perempuan (Milena Smit) and Zamiatin (Hovik Keuchkerian).

The central conceit largely remains the same. They also exist within the Vertical Self-Management Center but on one of the higher levels initially. The sequel is largely disconnected from the characters and events of the first film, although the audience learns more about the power dynamics within this system, namely how inmates divide into two factions. There are Loyalists, who only eat their fair share, and Barbarians, who eat as much as they can. Conflicts inevitably arise, presenting a far more violent world within this prison.

"The Platform 2" does begin tying into the first movie toward the end, with some surprises along the way. Ultimately, however, the sequel failed to capture critics' minds in the same way as the first. Robert Daniels wrote at RogerEbert.com that "neither the tacky ending nor the very existence of this second installment is earned. Instead, it languishes as the squeezing of the final drops of a once bright idea." Perhaps trying to turn "The Platform" into a franchise is like volunteering to enter the Vertical Self-Management Center — it's an ill-advised venture from the start.