The Biggest Unanswered Questions In Interstellar

Christopher Nolan movies have a reputation for being head-scratchers. Most of his films tend to play with time, linearity, or our perception of reality in one way or another. But while some Nolan movies prod at only one or two of these perplexing concepts, Interstellar is the rare film that leans into all three. Yet despite a plot that revolves around time relativity, non-linear storytelling, and inter-dimensional travel, most of the big questions it raises related to its high-concept premise are actually answered within the course of the film, although you have to be paying extremely close attention in order to catch them all.

Instead, the questions that are left unanswered by the film's end mostly have to do with the world outside the immediate story of Interstellar. Although we end the movie fully versed on what happened to Cooper, Brand, and humanity in general, there are a lot of smaller details that are left up to our imaginations. While it's understandable that Interstellar would have to be choosy about which of its many big questions it decides to address during its nearly three-hour runtime, there are a few puzzles we're still mulling over years after the film first hit theaters. Below, we walk through some of the biggest questions we have after watching Interstellar, and what little we do know about their answers based on what we learned from the movie.

What year is it at the beginning of Interstellar?

It's obvious that Interstellar takes place in the future, although just how far in the future the characters are at the beginning of the story is never clarified. We do receive a few clues that the world of Interstellar isn't tremendously ahead of our own: the characters' clothing and housing all seems to line up with current designs, and while the robotics technology is certainly more advanced than what we have today, it doesn't appear to be too far beyond where we are now.

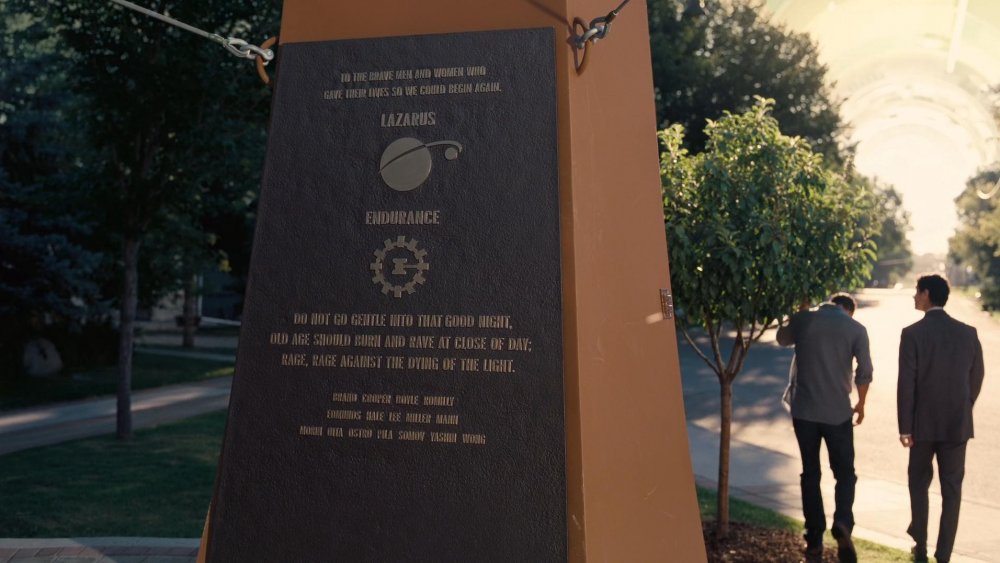

Additionally, in order for the Lazarus Missions to have departed ten years before the start of the film, humans would also have had to have made significant strides in space travel and cryosleep technology a decade before the movie started, at the latest. And Cooper looks to be in his late 30s or early 40s at the start of the movie, which means that his flashback to his career as a NASA pilot must have taken place within the past couple decades before the movie began.

One theory, referencing the book The Science of Interstellar, extrapolates that the wormhole near Saturn was discovered in 2019, placing the beginning of the movie around the year 2067. However, this is based on supplemental material, and not the film itself. While this seems a reasonable guess based on the information presented in Interstellar, we have no way of knowing for sure.

Why don't MRIs exist anymore in Interstellar?

One of the more curious throwaway lines in Interstellar happens early on, when Cooper (Matthew McConaughey) mentions that the brain cyst that killed his wife would've been diagnosable and treatable if MRI machines had still existed when she got sick. No further elaboration is ever given about why MRIs would have ceased to exist, and it's a curious piece of world-building when you consider that other types of technology still appear to be just fine. Not only are cars, trucks, and large farming equipment still prevalent, but the characters' clothing and resources speaks to a manufacturing industry that is still going strong. And while colleges are now only open to the very top echelon of students, that's probably because those students are going into highly educated fields, and it's reasonable to assume medicine would be among them.

Of course, other forms of technology have been scrapped on purpose, as part of the scapegoating of NASA. In response to the blight that wiped out most of Earth's crops, the history books were rewritten to teach that the moon landing was faked and that space exploration was futile, in the goal to keep humanity focused on fixing the problems of Earth, not dreaming of the stars. But MRI machines don't seem like they should have been lumped in with spaceships in that particular disinformation campaign, since they're used to diagnose patients here on Earth.

Could one of the gravitational anomalies of the 50 years prior to Interstellar have fried all existing MRI machines simultaneously? Perhaps, but in that case, why not build new ones? Interstellar never offers any clarity on what happened to the life-saving technology, so we're left to guess.

What caused the blight in Interstellar?

At the start of Interstellar, Earth's crops have been largely destroyed thanks to a global blight that eventually destroys every form of plant life it encounters. By the time we meet Cooper and his family, wheat and potatoes have been completely wiped out, and okra is undergoing its last-ever harvest season. Corn is one of the only viable crops that humans have left, but even that will eventually die out, leaving humans with no food source at all.

Professor Brand (Michael Caine) mentions at one point that the blight seems particularly suited to thrive in Earth's largely nitrogen-based atmosphere — much better suited than humans, surely, since we can't breathe nitrogen at all. Yet the film never provides much more detail on exactly what the blight is — whether it is bacterial, fungal, or even something extraterrestrial — or what caused it. We don't know if it evolved naturally, or if humans somehow caused it through our own actions. The blight affects every last person on — and off of — Earth, but how it came to be and why are left entirely up in the (unbreathable) air.

How did blight affect the non-food resources on Earth in Interstellar?

We don't get much of a look into how society is functioning outside of the Cooper farm in Interstellar, but before Coop heads off into space, we get a couple glimpses at what life is like in this dusty future version of the United States, and it begs some interesting questions about the supply chain. Although the school principal mentions during a parent-teacher conference that most students will grow up to become farmers, lots of other industries have to still be up and running in order to create the world in which the Coopers live.

Basic utilities all seem to still exist, and cars seem pretty common, which means that the fuel industry must still be chugging along. Most meals are corn-based, but the Coopers eat a variety of dishes requiring other ingredients that they don't seem to grow on their farm, implying that at least a modest grocery supply chain is still intact. Their clothes are dusty, but intact, so there must be a functional textile industry as well. And perhaps most bafflingly, there still appear to be professional sports teams — or at least, a well-funded local team with the money for new, custom uniforms. It causes us to wonder exactly how long the list of viable professions is in the world of Interstellar, and why everyone talks like the vast majority of people are farmers when the world they live in tells a markedly different story.

What happened to the other countries around the world in Interstellar?

Even in secret, NASA is still an agency run by the American government, so it's mostly unsurprising that Interstellar tells a pretty America-centric tale. All of the astronauts on the Lazarus missions and the Endurance are NASA-trained Americans, and every perspective we are offered on both the problems on Earth and the efforts to save humanity is an American one.

So what's going on in the other countries around the world while Brand is spending decades solving his equation to save the world? Surely they're not just sitting around waiting for the Americans to save the day, but we never get so much as a hint at what they are doing. Cooper does mention at one point that there are no more armies, which implies that instead of widespread famine prompting war, it has instead incentivized Earth's population to work the problem together. He also says that India's space program was disbanded around the same time as NASA. The teacher at Murph's school offers that the revised version of history claims that the moon landing was nothing more than Russian propaganda, implying that there's still no love lost between the two countries, although apparently not enough to warrant military intervention.

By the end of Interstellar, humanity — or at least the American part — has successfully escaped the dying planet. We're meant to understand that this means that all of humanity was saved and that "Plan A" was a success, but it sure would've been nice to have seen evidence of life outside of the future United States.

What were the gravitational anomalies 50 years before in Interstellar?

Throughout Interstellar, the characters encounter various gravitational "anomalies" both big and small, from the dust settling into binary stripes in Murph's bedroom to the wormhole near Saturn. By the end of the film, the source of many of these anomalies has become clear, and it's established that they aren't anomalies at all, but intelligent acts designed to serve a specific purpose. The humans of the future — referred to only as "They" — created the wormhole in order to give the humans of the past an escape route from Earth, and Cooper himself was responsible for the various anomalies in his daughter's childhood bedroom.

However, there are a number of other anomalies referenced in Interstellar that don't appear to have any sort of known purpose, such as the one that caused Cooper's instruments to malfunction when he was working as a test pilot. Romilly explains, "We started detecting gravitational anomalies almost 50 years ago. Mostly small distortions to our instruments in the upper atmosphere." But what these anomalies were and why they occurred are never really addressed. It seems reasonable to infer that "They" caused these as well, but for what purpose? Was it merely to get humanity's attention, and thus put the sequence of events leading to the developments of the film in motion? Or did the past anomalies serve some sort of other, unexplained function that we never learn about?

Why wasn't NASA using their giant space stations to farm while Brand worked on his equation in Interstellar?

During the time it takes the Endurance crew to visit two of the three potential new worlds in the new system at the other end of the wormhole, and for Cooper to finally collect and transmit the quantum data from the black hole Gargantua back to his daughter, Murph, only a couple years have passed for Cooper and Brand (Anne Hathaway), but decades have gone by back on Earth. By the time Murph (Jessica Chastain) receives and decodes the quantum data from her dad, she's older than he was when he first departed on his mission, even though she was only a child when he left. During that time, Professor Brand has been tirelessly working on his gravity equation, although Murph later finds out that he'd known for years it was unsolvable, and was merely trying to give the people on Earth a glimmer of hope, even if it was false hope, until they eventually suffocated to death in the degrading atmosphere.

However, for that entire time, Professor Brand and Murph are working on the massive space station that we see at the end of the film orbiting Saturn. Once Cooper Station is in space, we see that its inhabitants are able to use the massive amount of space inside it to farm, creating food for the humans who have escaped earth. So why weren't they using the stations for that purpose when they were still on earth? Granted, they couldn't have used every inch of real estate for farming if they were tied down by gravity, but it seems like they should've been able to figure out a way to use some of it, especially given how much time they had.

When did Edmunds die in Interstellar?

When the Endurance leaves Earth, it's only been 10 years since Wolf Edmunds and the other scientists first departed on the Lazarus missions, but by the time Brand finally makes it to the planet where he'd set up camp, nearly 90 years have passed, and Edmunds has died. It's implied that he was killed when a rockslide destroyed the cryochamber in which he was hibernating, although it's also possible that he died due to a malfunction in the chamber itself and the rock slide happened afterward.

That Edmunds didn't survive until Brand was able to reach his planet isn't tremendously surprising, but what's more interesting is the question of when he died. Although Edmunds was only sent to his planet with two years' worth of resources, he could extend that almost indefinitely with his cryogenic pod, meaning that when Brand and the Endurance first emerged from the wormhole twelve years after Edmunds first departed, only a year or two would've passed for Edmunds — assuming his pod was still functioning. Even after losing another 23 years on the water planet, he could've still been alive, and it's possible that if Cooper had taken Brand's suggestion and headed straight to his planet, they would've arrived in time to save him. Then again, if they'd never gone to Mann's planet, then Cooper wouldn't have had to jettison himself into the black hole, and he wouldn't have been able to save humanity by giving Murph the information she needed.

What happened to the other 9 members of the Lazarus missions in Interstellar?

When the Endurance departs on its mission, they're heading to a system in a distant galaxy with three potentially habitable planets, based on the data sent back from three of the astronauts on the Lazarus mission. However, 12 astronauts originally departed ten years earlier, with a mission to each explore one of twelve possible worlds. They all knew that the chances of their world being able to support human life were slim, and that if their planet wasn't a good candidate for relocation, that they'd be on their own for the rest of their lives.

However, while it's implied that none of the other nine worlds the Lazarus astronauts visited were viable, and that those astronauts eventually died, we don't actually know that for sure. It's possible that one or more of the planets was viable, but something happened to the astronaut or their equipment before they could send back the electric "thumbs up" that would send NASA to them. Or it's possible that one or more of the astronauts is still slumbering away in cryosleep — not really living, but not truly dead either.

How far in the future are "They" in Interstellar?

Throughout Interstellar, humanity receives help from "Them," mysterious beings that the scientists of NASA assume must be benevolent extraterrestrials. However, by the end of the film, Cooper realizes that "They" aren't aliens at all, but actually the humans of the future, who have figured out a way to exist and navigate in five dimensions. This creates a bootstrap paradox, in which the existence of the humans of the future depends on them existing to help the humans of the past, but that's easy enough to explain in the world of Interstellar, where time may not actually be linear at all.

What we don't know is exactly how far in the future these five-dimensional humans are, or if they even exist in a specific time at all. Once Murph solves Professor Brand's gravity equation, it opens up a whole new world for humanity. Not only are they able to escape their dying planet, but they're able to thrive in new ways that they never could on Earth. Perhaps Murph's breakthrough is precisely what lays the groundwork for these new future humans, meaning that they're not as far ahead of the humans aboard Cooper Station as one might think. Then again, it could take centuries or even millenia for humans to evolve to that point.

Did Murph and Tom ever reconcile in Interstellar?

At the beginning of Interstellar, Cooper's two children Murph (Mackenzie Foy) and Tom (Timothée Chalamet) function as pretty typical siblings, neither best friends nor mortal enemies, but simply two kids who mostly get along and occasionally get under each other's skin. Even the fact that Cooper clearly seems to favor Murph over Tom doesn't really seem to be a source of bad blood between any of the family members, even if it probably should be.

All that changes, though, when Cooper leaves aboard the Endurance. Murph spends the next few decades nursing a grudge against her father, while Tom does his best to remain in touch, even long after Cooper stops responding thanks to the 23 years he loses on the water planet. During that time, Tom (Casey Affleck) marries and has two children, although his oldest dies a few years later of complications due to the dust-saturated atmosphere. Murph, meanwhile, throws herself into her work with Professor Brand and rarely visits home, but eventually returns to try to convince Tom to move his family out of their old farmhouse and underground with her. When Tom refuses, Murph decides to trick him, luring him away so she can essentially kidnap his family.

She doesn't actually manage to leave before Tom returns, and by then she's realized she has what she needs to solve the gravity equation and save humanity, but while Murph gives her brother a relieved hug upon his return, Tom doesn't look nearly as ready to bury the hatchet. Despite Murph's great accomplishment for humanity, the actions she took with her brother's family significantly overshot the boundaries he'd set. But we never see Tom again after that, making us wonder if the end justified the means for him, or whether Murph's actions damaged their relationship permanently.

Why didn't any other humans ever attempt to travel to Edmunds' planet in Interstellar?

After Cooper emerges from the black hole, "They" wind up dropping him off near Saturn, right where a Ranger from Cooper Station was passing by to pick him up. However, while it's only been a few minutes for Cooper since he jettisoned himself from the Endurance in order to send Brand on to Edmunds' planet, it's been over 60 years for the people of Earth due to the time slippage in Gargantua. Murph solved the gravity equation thanks to the quantum data Cooper provided when she was around her early 40s, and even if it took a while to actually implement it and launch the space stations, humans have had decades in which to find a new home.

And yet, Cooper Station and others like it are still content to just float around near Saturn, despite never having received conclusive data about the worlds just on the other side of the wormhole. We know the wormhole still exists, since that's how Cooper goes to return to Brand at the end, and as far as NASA knows, one of those planets from the Lazarus mission could still be a viable new homeworld. It's understandable that they wouldn't want to send an entire station through as a guinea pig, but why not send a few Rangers after the Endurance went silent? It seems like by the time Brand arrived on Edmunds' planet, a whole human colony could've already been set up and ready to go, and she wouldn't have had to be alone at all.