The Backstory Of The Lord Of The Rings Dwarves Explained

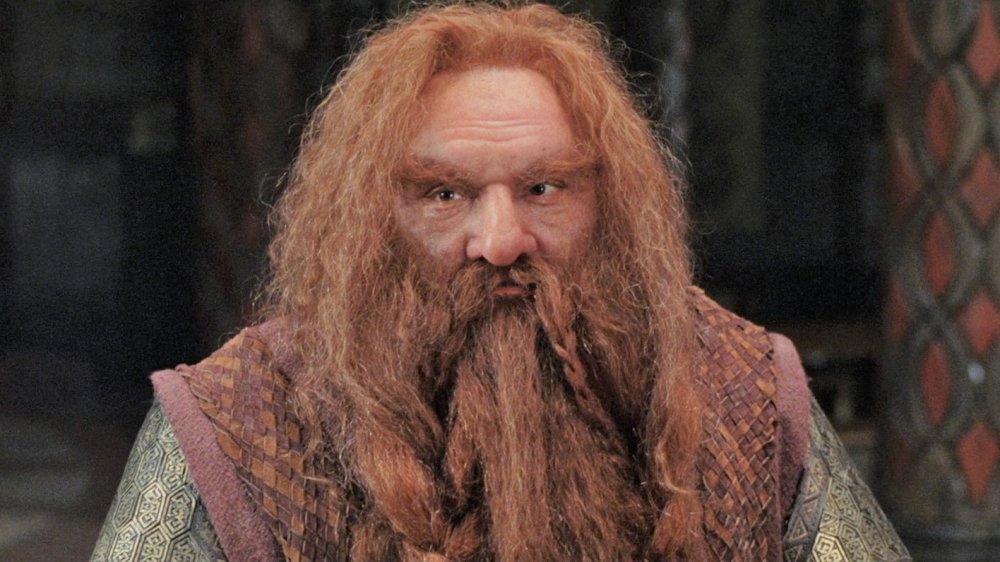

From following a bumbling baker's dozen as they trip their way through The Hobbit to watching Gloín's son defeat an elvish prince of Mirkwood in an honest game of "who can slaughter the most bad guys," dwarves have left their mark all over Middle-earth history. But there's more to these abbreviated warriors than braided beards and an admittedly hefty dose of humor.

J.R.R. Tolkien's dwarves have a rich backstory filled with underground mansions, sharp axes, epic wars, double-crossing behavior, powerful rings ... and gold. Lots and lots of gold. How much gold? Suffice it to say that a few of these guys would make Buffet, Bezos, and even Scrooge McDuck look like paupers.

With so much dwarvish lore out there, we thought we'd take a deep dive into the dwarves of Middle-earth in order to see what makes them so special. We'll start with a quick stroll through this hardy people's one-of-a-kind history. From there, we'll dive into some of the things that make their culture stand out like a sore thumb against the ostentatious men, froufrou elves, and beardless hobbits that surround them on all sides. So, without further ado, here's the backstory of the dwarves from J.R.R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit stories.

The origin of the dwarves

The dwarves have a very unique origin story. For perspective, the races of both elves and men are created by Ilúvatar, the creator of Middle-earth, and they're known far and wide as his "children." And the dwarves? Well, they're left out of this happy family tree — at first, anyway. They're brought into being by Aulë, one of the Valar — that is, Ilúvatar's angelic guardians of Middle-earth.

Known to his dwarven sub-creations as Mahal, Aulë fashions the dwarves in the very early days of Middle-earth's existence. Impatiently waiting for Ilúvatar's children to arrive, the angelic smith decides that he'll secretly (and disobediently) make his own children instead. He shapes the first batch of his very own kiddos, known as the "Seven Fathers of the Dwarves," deep under a mountain in Middle-earth.

Eventually, Ilúvatar, who knows all, calls Aulë out on his impatience and reveals to him that while he may be a master craftsman, he lacks the power to give each dwarf their own will. Seeing that he has merely created puppets, Aulë repents and offers to destroy his empty creations. However, Ilúvatar opts to spare his repentant servant's handiwork, giving the dwarves independent wills and adopting them into his "family" of children. Each of the Seven Fathers is then put to sleep, and they're spread across Middle-earth, where they remain in silent slumber until the elves finally awake, and the action starts to heat up.

The early years in the history of the dwarves

Once the dwarves do wake up, it doesn't take long before they start busily setting up shop. The first dwarf to stir from his slumber is named Durin, the father of the dwarven clan known as the Longbeards. Durin wanders around a bit before settling down in the area that eventually becomes Khazad-dûm — or Moria, as the elves call it later on.

Four of the other dwarven fathers wake up far to the east, and they aren't talked about much. However, the last pair of dwarven fathers appear in the Blue Mountains to the west of Khazad-dûm, and they found the famous cities of Belegost and Nogrod. This pair of cities plays an important part in the First Age of Middle-earth history, as the inhabitants befriend the elven exiles who return to Middle-earth at the beginning of the age and join them in their fight with Sauron's original master, Morgoth. They also help the elves carve out vast underground palaces, create gems and weapons for them, and even aid them in battle.

However, they also infamously kill an elven king when he refuses to pay them, starting a bitter feud that sparks several retaliatory conflicts and feeds into a dwarvish reputation that they don't always fight on the side of "the good guys." Eventually, the entire region is sunk under the sea at the end of the age, and the surviving dwarves head east to join their relatives in the Misty Mountains.

Khazad-dûm and glory

During the Second Age of Middle-earth, many of the survivors of Belegost and Nogrod join the thriving kingdom of Khazad-dûm, where their knowledge and experience only launch the dwarven realm into further glory. At this point, the western gates of Khazad-dûm open right up into the elvish kingdom of Eregion — the region where the Fellowship of the Ring is harassed by Saruman's spying birds and almost gets buried in snow. Here, the Doors of Durin welcome every one of their elven neighbors that decides to "speak, friend, and enter."

As the age plays out, it initially sees a healing of the relationship between the elves and the dwarves. In fact, they even allow Galadriel to journey through their subterranean passages so that she can visit Lothlorien for the first time. When war erupts between the elves and the resurgent Sauron (at this point, Morgoth is defeated and Sauron has taken his place), the dwarves pour out of Khazad-dûm to aid their friends.

However, their help comes too late, and they're forced to retreat back into their mountain kingdom and to lock the doors. After that, the dwarves largely stay out of the ongoing conflict. Even during the War of the Last Alliance at the end of the age (the opening scene from The Fellowship of the Ring), only a handful of dwarves are willing to join in the fighting, with those from Khazad-dûm supporting the elves while those from other dwarven houses link up with Sauron.

Dragons and a Balrog

The Third Age starts off fairly quiet. The dwarves go on busily mining in their underground mansions, and Khazad-dûm, in particular, continues to thrive. Roughly 1,300 years into the age, orcs begin to repopulate and harass the dwarves, but overall, the chill life of the busy subterrestrial miners remains undisturbed.

Then, in the year 1980 of the Third Age, the dwarves of Khazad-dûm unearth a Balrog — and yes, it's the same one that faces down Gandalf over a thousand years later. The demon kills their king, and the Longbeards flee their ancient home, scattering across the map in the process. Some of them find their way to the Lonely Mountain in Erebor, where they officially establish a new "Kingdom under the Mountain."

Many of the scattered dwarves also head north and settle in the Grey Mountains. While the Khazad-dûm refugees begin to rebuild their strength for a few centuries, this relocation to the north puts them in close proximity to an area populated by dragons. Eventually, conflict erupts with these fiery new neighbors, and most of the surviving dwarves are forced to relocate all over again, this time joining their kin in the thriving young kingdom under the Lonely Mountain. Unfortunately, this isn't far enough to keep away their new nemeses. One dragon, in particular, named Smaug the Golden, hears of the prosperous kingdom and decides to pay it a visit.

Dwarven realms in exile

When Smaug attacks the Lonely Mountain, it spells doom for the Longbeards. Already driven out of Moria by a Balrog, the few surviving dwarves once again find themselves on the run from Smaug. Many of these head further east to the Iron Hills (the same area that the backup dwarven army comes from in The Hobbit: The Battle of Five Armies). Another group of dwarves under their king, Thrór, head south, where they adopt a wandering, homeless lifestyle.

After this second diaspora, the dwarf-king Thrór becomes tired of defeat and lonely wanderings and starts to go a little bit out of his mind. He irrationally decides to head back to Moria to scout out the land, where he's quickly killed and mutilated by the orcs that have taken up residence there in the dwarves' absence. This regicide sparks the War of the Dwarves and Orcs.

Over the next three years, dwarves from all of the seven households gather together and then attack the orcs of the Misty Mountains. The war culminates with an epic battle in front of the gates of Moria, where, according to the books, they kill the Orc leader Azog. However, in The Hobbit films, the pale orc leader is shown surviving the battle, instead. After their victory, the dwarves refuse to repopulate Moria, knowing that there's a Balrog on the loose, and they scatter back to their homes, leaving the Longbeards still without a home.

A quest and a war

At this point, we've brought the story up to the common tale seen on the silver screen. Roughly 150 years after the battle with Azog, Thorin Oakenshield meets Gandalf the Grey in the inn at Bree. From there, they recruit a dozen dwarves and a timid hobbit and set out on a quest to reclaim their treasure from Smaug.

After the dragon is defeated and the Kingdom under the Mountain is restored, the dwarves find a new lease on life. With a new infusion of gold and jewels in hand, they set up shop as one of the dominant players in northern Middle-earth ... just in time for the War of the Ring.

While the dwarves aren't shown much throughout The Lord of the Rings, they do play an important side role by helping to keep the forces of evil at bay in the north. In fact, in the appendix for The Return of the King, Gandalf explains that Dáin, the dwarven king at the time, is actually killed in the fighting. Nevertheless, the dwarves and their allies successfully keep the northern regions of Middle-earth safe while the events in the main narrative unfold.

Fourth Age aftermath

After the War of the Ring wraps up, Gimli heads back to the Lonely Mountain and brings a group of his people back to Rohan — to Helm's Deep, to be precise. There, the dwarves establish a new home in the Glittering Caves, an area that Gimli himself, in The Two Towers, dubbs one of the "marvels of the Northern World." Gimli, now the lord of the Glittering Caves, also helps to repair the broken gates of Minas Tirith around this time.

It's also said that king Durin VII, the last king to be named after the founder of the Longbeards, finally reclaims the now Balrog-less Khazad-dûm and restores it to its former glory. Eventually, the dwarves begin to diminish in importance, and their race slowly dwindles until it comes to an end at an undisclosed point.

Perhaps the most fitting ending to the dwarven history is the touching story that Gimli, friend to elves and avid devotee to Galadriel, eventually gets permission to board a ship in the same way that Frodo and Bilbo do at the end of The Return of the King. He sails west with his friend Legolas, seeking Galadriel and an earthly retirement in the Blessed Realm beyond the sea, and he's reportedly the only dwarf to ever be given such an honor.

Characteristics of the dwarves

Alright, so far we've discussed the story of the dwarves throughout Tolkien's works, but we haven't actually addressed too many of the things that make them unique — especially compared to elves, men, and hobbits who soak up most of the rest of the Middle-earth spotlight. And yet, there are a ton of things that make dwarves distinctly different from all three of those groups.

Take their basic characteristics as a starting point. Dwarves are short but not quite as short as hobbits, who are typically between two and four feet tall. In comparison, dwarves usually come in at around four to four and a half feet tall. They're also tremendously strong, stout, and stocky. While hobbits are known for their clean-shaven faces, dwarves are specifically marked by their remarkably long beards, which they wear with great pride.

When Aulë first created them, he designed the dwarves to be tough in order to endure the perils of Middle-earth. They're also famously stubborn and remain incredibly loyal to their friends and bitter to their enemies. While there's no hard and fast number regarding their lifespan, they definitely outlive men and often live to be hundreds of years old, with Dwalin, in particular, living to the ripe old age of 340.

The customs and culture of the dwarves

The Seven Fathers of the dwarves each founded a clan or household. Along with the Longbeards, there were the Firebeards and Broadbeams (the dwarves that were heavily involved in the First Age). The other four houses — the Ironfists, Siffbeards, Blacklocks, and Stonefoots — all originated in the far eastern regions of Middle-earth and were only minorly involved in the larger historical narrative.

Culturally the dwarves have many things that they share with the other Free Peoples of Middle-earth, although they put their own unique spin on each one. Their music, for instance, is highly developed, and in The Hobbit book, all of Thorin's companions show off their musical skills on a variety of instruments. However, unlike the music of the elves, most of their songs aren't light and ethereal. They're slow, methodical, and moody.

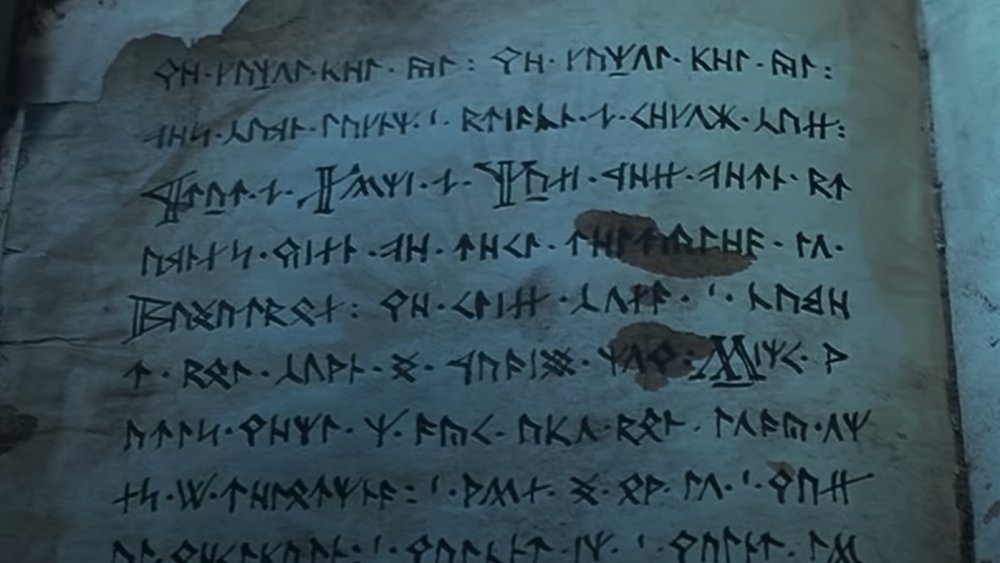

Their language is also very unique. The Silmarillion states that Aulë invented a language for them and began to teach it to them right at their inception. It also points out that their language is "cumbrous and unlovely," and it's kept very secret. In The Fellowship of the Ring, Gandalf even refers to "the secret dwarf-tongue that they teach to none."

The truth about the dwarven religion

While they aren't recorded acts of dwarven worship (something Tolkien wisely leaves out of most of his writings), the dwarves do have the closest thing to a Middle-earth religion. In The Silmarillion, it's said that the elves believe that, at death, dwarves simply return "to the earth and the stone of which they were made." However, the dwarves themselves have a much less nihilistic opinion of their afterlife.

They believe that Aulë told the first dwarf fathers that their kind would have a place among the Children of Ilúvatar in "the End" — that is, the vague, unknown end days of Middle-earth that were to come after the equally vague "Last Battle." They hold the belief that Aulë cares for them after death, gathering them together and preparing them to do their part in healing the hurts of the world in the end times to come.

They also believe that the Seven Fathers of the Dwarves literally come back to life, reincarnating a set number of times in new bodies — hence the whole "Durin the VII" being the last king of Khazad-dûm. Yeah, he's not just another dude to the dwarves. He's very literally thought to be the seventh and last reincarnation of the founder of their clan.

The secret of the dwarf-women

Just in case there was any doubt at this point, there are, indeed, dwarf-women, a fact that is plainly stated in the appendix to The Return of the King. However, they're kept very secret and don't leave home often. Apparently, dwarves missed the progressive memo. They also look almost exactly like their male counterparts and only make up roughly a third of the total dwarven population. In fact, dwarf-women are so rarely seen or even heard about that the only dwarf-woman named in all of Tolkien's works is Dís, the mother of Fili and Kili.

This secrecy and similarity of looks ultimately leads the race of men to assume that there are no dwarf-women. Instead, rumors circulate that the dwarves simply "grow out of stone," an assumption that is laughably false (to the dwarves, at least). The scarcity of dwarf-women naturally means dwarves repopulate at a very slow pace. This is exacerbated by the additional facts that when a dwarf marries, they do so for life, and many dwarven men and women don't bother falling in love or marrying in the first place. Nevertheless, dwarf-women are very much alive and real.

The dwarves are incredible smiths and architects

Any backstory about dwarves would be incomplete without touching on the fact that the subterranean race produces hands-down the best craftsmen in all of Middle-earth. The countless centuries spent digging underground, working with metals, and shaping solid stone helps to develop dwarven smithcraft and architecture into masterful arts.

As architects, the dwarves are famous for building their own mansions, with Khazad-dûm and the Kingdom under the Mountain being the most famous. In addition, they help to build multiple underground elven halls, especially in the First Age.

When it comes to smithcraft, dwarves are basically in a running competition with themselves. They're constantly being hired by the elves, are unmatched when it comes to working with steel and chain mail, and are famous for their work with metals — especially mithril, the rare metal that Frodo's armor is made from. Telchar is the most famous dwarven smith, and he personally forges Aragorn's sword — the one that cuts the ring from Sauron's hand — millennia before the ranger is even born.

The seven unrulable rings

Finally, we need to talk about the seven dwarf-rings. After all, we see the nine rings corrupt the Black Riders, the three elven rings are busy being used by Galadriel, Gandalf, and Elrond, but what about the seven for the dwarves?

After Sauron creates the One Ring to rule them all, he captures 16 of the other elven Rings of Power and begins distributing them. He gives nine of them to men, who quickly fall under his control. He gives the other seven to the dwarf-kings — although the dwarves believe that one of these was untainted by the Dark Lord and given to them directly by the elves. Regardless, Sauron finds that the tough hardihood of the dwarves makes them more or less impervious to his direct control.

Instead of falling under Sauron's domination, The Silmarillion states that the dwarf-rings kindle "wrath and an over-mastering greed of gold" in the hearts of their owners. The rings amplify their skills and desires, and each one is supposed to have been the foundation of a great dwarven hoard of wealth. Eventually, four of the dwarven rings are destroyed by dragon fire, while the other three are eventually recovered by Sauron, leaving the dwarves to manage their wealth without their super-powered jewelry.