Samurai Movies You Need To Watch

Western cinema has no shortage of popular genre-specific heroes. We've got cowboys, superheroes, cops, pirates, and more, but one largely untapped pool of heroes on this side of the Pacific Ocean is that of the samurai. Based on the real-life Japanese military caste that lasted from the 12th century to the late 19th century, samurai in films are known for their fierce loyalty, their deadly precision with the sword, and an unswerving commitment to bushido — the codes of honor governing the way of these warriors.

You may not see samurai on the big screen as often as you see Jedi Knights or Avengers, and that means if samurai flicks are your cup of tea, you might have to look a little bit harder. Fortunately, some of Japan's greatest directors spent most of their careers making samurai films, and you might be surprised to learn just how much their work influenced American movies like Westerns and even space operas like Star Wars. And while most of the best samurai cinema has to offer is made in Japan, America isn't without its own noteworthy samurai flicks.

Whether you're a fan of the genre or a newcomer, we're confident that you absolutely need to watch these samurai movies.

Seven Samurai is the OG samurai movie

The name that rightly dominates any discussion of great samurai movies is Akira Kurosawa. The late director not only made some of the best samurai movies you're likely to come across, but even beyond that genre, he's regarded as one of the most influential directors of all time. And the film most often associated with him is 1954's Seven Samurai.

The heroes of Seven Samurai are ronin, samurai without masters. Led by Kambei (Takashi Shimura), the seven warriors unite to protect an otherwise helpless farming community from merciless bandits. Along with facing the bandits themselves, the ronin train the villagers into a makeshift militia, and the nearly four hour epic culminates in a huge, bloody battle.

If the plot of Seven Samurai sounds familiar it's because it's been copied over and over again. The classic Western The Magnificent Seven is a remake of Seven Samurai that transplants the story to the Wild West, and plenty of other Westerns have similarly found inspiration in the film. The story of veteran heroes training simple, peaceful townsfolk into soldiers has been copied in everything ranging from comedies like The Three Amigos to episodes of The Clone Wars and The Mandalorian. And the trope of assembling the team has echoes in heist films like Ocean's Eleven, war movies like The Dirty Dozen, and even superhero flicks like The Avengers and Justice League.

Unforgiven is a Japanese remake of an American Western

If you're a fan of Westerns, you're likely familiar with 1992's Unforgiven, Clint Eastwood's practically flawless movie set in the Old West about an aging gunslinger who sets out on one last job. But what you may not know is that Korean director Lee Sang-il remade Unforgiven in 2013, with Ken Watanabe cast as Jubei, the retired samurai in place of Eastwood's Bill Munny.

Set in Japan's Hokkaido frontier, the plot of 2013's Unforgiven is pretty close to the original's. Jubei and his old friend Kingo (Akira Emoto) are lured out of retirement by the promise of a handsome reward for killing two brothers who disfigure a prostitute early in the film. They're joined by the younger Goro (Yûya Yagira) who makes bold claims about a triumphant and violent past. The trio's clash with Oishi (Kôichi Satô) — the local lawman determined to stop anyone looking to make good on the prostitutes' contract — is destined to end badly for everyone involved.

Unforgiven is, as London Evening Standard's Charlotte O'Sullivan writes, a "visually rich, tightly wound epic" that "reminds us that there are no easy moral choices." It's a faithful echo of its source material, with the added benefit of Ken Watanabe's singular talent.

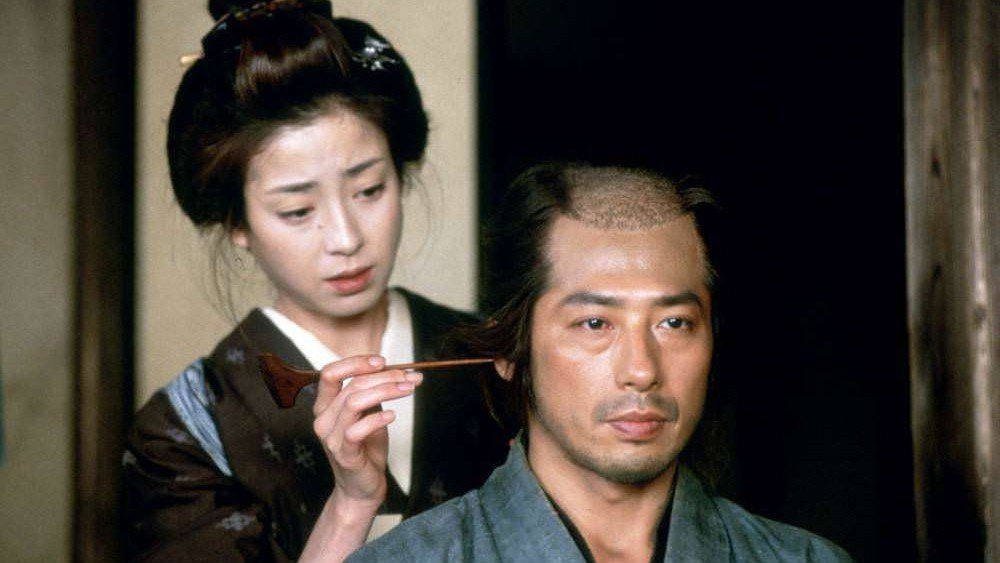

The Twilight Samurai is a relatable tale of loss, love, and family

The Twilight Samurai is a different kind of samurai movie. Its hero, Seibei Iguchi (Hiroyuki Sanada), is a low-level, poor samurai who works as a clerk. With his wife dying early in the film, Seibei is forced to raise his two daughters alone on his modest stipend. When Seibei's old friend Tomoe (Rie Miyazawa) begins to regularly visit Seibei and help take care of his girls, the samurai falls in love. Sadly, Seibei is shamed by his social status and initially refuses to marry his old friend.

While The Twilight Samurai has its share of swordplay, neither action, adventure, nor intrigue are the focus of the film. It's more interested in character than other offerings of the genre, and as such, Seibei is a lot more relatable than your average fictional samurai. While most of us probably don't deal with a lot of far-reaching adventures involving assassination and revenge, things like loss, love, and the difficult balance between work and family are much more familiar concepts.

The Twilight Samurai is a refreshing and uncharacteristically upbeat samurai film, and that distinction helped it earn a dozen Japanese Academy awards, along with a nomination for Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film in America.

Throne of Blood is Shakespeare in ancient Japan

One of the reasons why William Shakespeare's plays endure centuries after the Bard's death is their surprising relevance beyond not only the time Shakespeare was writing but beyond even the society for which he wrote. Director Akira Kurosawa proved this better than anyone with 1957's Throne of Blood, an adaptation of Shakespeare's tragedy Macbeth.

While Macbeth is set in Scotland, Throne of Blood finds its home in Japan, and the setting change is the biggest difference between the films. Throne of Blood's protagonist is General Washizu (Toshirô Mifune), who at first seems as loyal to his lord as any samurai. After Washizu is visited by a strange spirit who tells him that one day he'll become the lord of Spider's Web Castle, he tells his wife, Asaji (Isuzu Yamada), of the spirit's prophecy. Just as Lady Macbeth did with her husband, Asaji urges her partner to make the spirit's prediction come true by murdering the lord and taking his place. After that, like his Scottish inspiration, Washizu finds himself well past the point of no return and on a road that can only end with a bloodbath.

Throne of Blood is not only essential for fans of samurai films but for admirers of Shakespeare's work. Take it from The Guardian's Derek Malcolm, who calls the film "possibly the finest Shakespearean adaptation ever committed to the screen."

If you want epic battles and bloody sword fights, watch 13 Assassins

In the wake of 2002's The Twilight Samurai's success, the doors opened for more filmmakers to dive back into the long neglected samurai genre, and among them was Japanese director Takashi Miike's (Audition, Ichi the Killer) 2010 remake of the 1963 classic 13 Assassins. Set in 1844, the story follows a group of samurai determined to take down a powerful and cruel lord whose rule could mean nothing but horror for the future of Japan.

While it may remake another film, 13 Assassins often feels a lot like Seven Samurai, including its length. At close to two and a half hours, 13 Assassins begins relatively slow but climaxes with an insanely spectacular and prolonged battle between the heroes and the villain's army. It's an epic set piece that includes an abandoned town converted into a deadly labyrinth of booby traps. The film is not only heralded as one of Miike's best, but it went a long way to revitalize the dormant samurai genre. As Spectrum Culture's David Harris writes, 13 Assassins is "a reverential and vital film in a genre that many may have thought as moribund and passé."

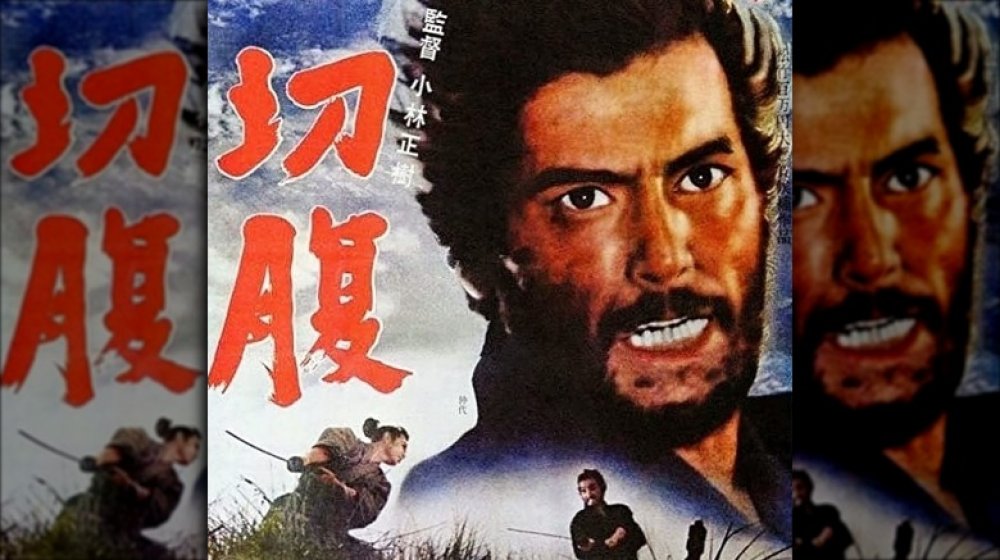

Harakiri is a powerful film that's critical of the samurai code

By 1962, Japanese studios were churning out samurai movies at an impressive rate, often with more focus on the action and little care for the emotional power of the films. Director Masaki Kobayashi went against the grain with Harakiri, a film set in Japan's Tokugawa period. Harakiri opens on the ronin Tsugumo Hanshiro (Tatsuya Nakadai) requesting permission to perform seppuku — ritual suicide — at a clan's mansion. The clan elder, Saito (Rentarô Mikuni), tells Tsugumo he will grant the ronin this permission but only after a story. What follows is a complex struggle that too many details would ruin, but suffice it to say, Tsugumo is there for more than just his own death.

Kobayashi was known for films that were more critical of the bushido code so many samurai held sacrosanct, and Harakiri is a classic example. Case in point, we're subjected to one of the film's most grueling and brutal scenes early in the story, when a ronin is forced to commit seppuku with nothing but a dull bamboo practice blade. Visually striking and emotionally heartbreaking, Harakiri is a classic and utterly essential samurai film.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai is an American spin on a Japanese genre

Perhaps the biggest departure from the norm on our list is Jim Jarmusch's 1999 crime drama Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai. This one doesn't take place in Japan, and stranger still, we're not sure exactly where in America it's meant to be set, as we're never given the name of a city.

Forest Whitaker stars as the titular hitman who binds himself in service to Louie (John Tormey) after he saves Ghost Dog's life. But Ghost Dog isn't just any hitman. When he's not working, we find him tending to his pigeons, meditating, and studying Hagakure — a collection of conversation from the early 18th century about the meaning of bushido. Ghost Dog sees himself as a samurai and is a strict follower of bushido. The fact that Ghost Dog continues to work for Louie, and eventually begins taking out his boss' competition when Louie's life is in danger, is proof enough of his devotion to the code. Even after it becomes clear Louie isn't returning Ghost Dog's loyalty, the hitman refuses to lift a hand against him.

Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai is a uniquely moving and surprisingly funny film about a man who refuses to let go of who he is in the face of a hostile world.

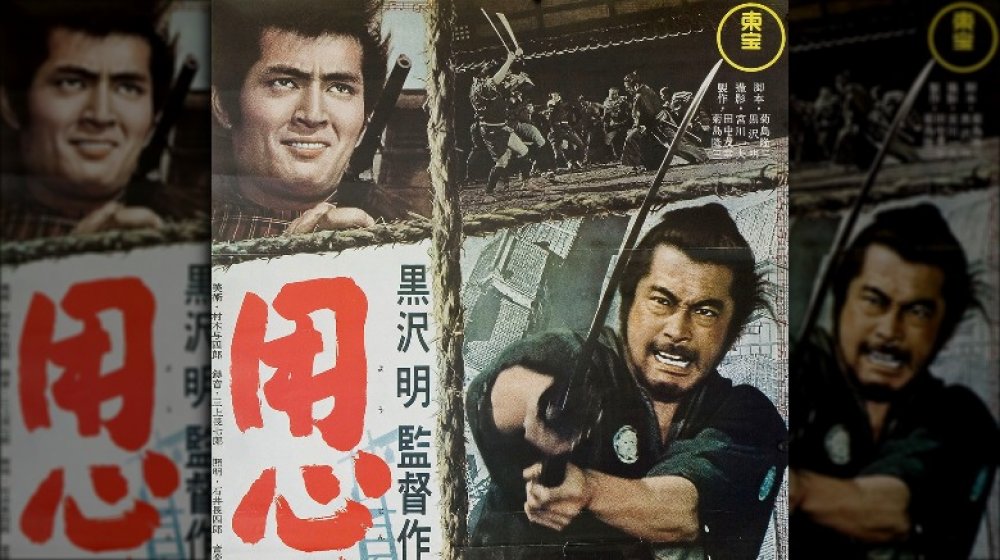

Yojimbo and Sanjuro inspired a classic Clint Eastwood character

By the early '60s, Toshirô Mifune had already starred in a number of Akira Kurosawa's films, including 1954's Seven Samurai and 1957's Throne of Blood. In 1961, Mifune worked under Kurosawa's expert direction in Yojimbo, the first of a pair of films with Mifune playing impoverished samurai Sanjuro (a moniker that means "30 years old"). Each would prove to be some of the best that samurai cinema has to offer.

When we first meet Sanjuro in Yojimbo, he's found himself in a town where a feud between two warring clans is raging. Rather than work for one clan or the other, Sanjuro winds up getting hired by both sides as part of a secret plan he hopes will wipe out both groups. In 1962, Mifune starred in the follow-up, Sanjuro, in which the titular hero teams up with a group of samurai intent on fighting a corrupt lord.

In some important ways, what's most influential about Yojimbo and Sanjuro is felt more powerfully in Western cinema. Yojimbo's antihero is credited as the prototype for the similarly amoral Man With No Name — the character Clint Eastwood made famous in Sergio Leone's spaghetti Western Dollars trilogy. While Mifune's ronin seems less like Eastwood's gunslinger in the comedic Sanjuro, in the much darker Yojimbo, the similarities between the characters are clear enough for anyone to recognize.

Kill Bill is Quentin Tarantino's take on the samurai film

Kill Bill is Quentin Tarantino's love letter to martial arts and samurai cinema, a stylistically beautiful revenge epic and a story too big for a single film.

In 2003's Kill Bill: Volume 1, we know Uma Thurman's merciless ex-assassin only as the Bride, and when we first meet her, we have no idea why she's arrived at Vernita Green's (Vivica A. Fox) suburban home in a ridiculous garish yellow truck or why the two proceed to beat the crap out of each other. Eventually, we learn the Bride left the employ of the enigmatic Bill (David Carradine) to pursue a normal life. But at the rehearsal for her wedding, Bill found her, and he and his top assassins killed all of the rehearsal guests and left the Bride for dead. Miraculously, she survived and began her path of vengeance.

The first film is heavier on action, particularly in the climax in the Japanese restaurant, the House of Blue Leaves. There, the Bride has a bloody, darkly hilarious, and visually stunning showdown with the sword-wielding Crazy 88s, the sadistic Gogo Yubari (Chiaki Kuriyama), and the yakuza crimelord O-ren Ishii (Lucy Liu). Kill Bill: Volume 2 dives deeper into the Bride's background and the reasons for her war with Bill. And as one of Tarantino's best movies, Kill Bill is a wonderful cinematic achievement that needs to be experienced at least once.

The Blind Swordsman: Zatoichi is bloody, beautiful, and funny

You may not be familiar with the name Zatoichi, but in Japan, the fictional blind swordsman is a lot more recognizable. Between 1962 and 1989, Japanese actor Shintaro Katsu starred as Zatoichi in 26 films, along with 100 episodes of the Zatoichi TV series between 1974 and 1979. Takeshi Kitano revitalized the hero with 2003's The Blind Swordsman: Zatoichi, which he directed, wrote, and starred in as the titular samurai.

In the 2003 film, Zatoichi is an otherwise peaceful swordsman who helps a pair of sisters in their quest to make criminals pay for murdering their parents. The film is a series of contradictions that shouldn't work, but somehow, they do. It's as bloody a samurai film as you'd expect, while at the same time, it manages to be hilarious and often beautiful. Kitano's unique style makes these warring notes work perfectly, with big laughs and bigger, stylized bloodletting. As Time Out's Geoff Andrews puts it, The Blind Swordsman: Zatoichi is "fast, funny, fabulous to behold."

Samurai Assassin is a tragic film with a brutal ending

In many ways, 1965's Samurai Assassin is a tragedy of Shakespearean magnitude. The film's hero is Tsuruchiyo Niiro (Toshirô Mifune), a ronin who knows he's the illegitimate son of a powerful nobleman but not his actual identity. Desperate to be recognized as a true samurai, Niiro joins a plot to assassinate Lord Ii Naosuke (Hakuô Matsumoto). He hopes that helping to kill the controversial lord will earn his father's pride and encourage him to reveal himself.

Based on the actual event known as the Sakuradamon incident, Samurai Assassin can get bogged down at times with exposition meant to provide the necessary historical detail. But the payoff — a stunning, brutal battle in the snow at the end of the film — makes the wait more than worth it. Fans of happy endings may want to skip Samurai Assassin, as it includes a surprise twist that makes everything that unfolds seem all the more stark and senseless. Regardless, it's a captivating tragedy dealing with the historical events which, for better or worse, eventually lead to the end of the samurai.