Sci-Fi Movies That Scientists Can't Stand To Watch

Science fiction has come a long way from the time when it didn't get much consideration outside pulp magazines and B-movies. Ironically, the greater emphasis on science fiction in our popular culture can be a little frustrating to a very specific group of people — scientists.

One reason sci-fi can bug anyone who knows more about science than your average Joe is that the scientific errors and inconsistencies can make it a lot tougher to enjoy the stories. Sure, we all have to suspend our disbelief and remember the movies we watch are just movies, but it shouldn't be tough to imagine why this bothers people for whom science is more than just a curiosity. Imagine being passionate about science — perhaps enough that you actually work in a scientific field — and looking forward to a movie about the thing you love, only for it to get everything wrong.

Perhaps a less obvious reason is that the very movies that depend so much on scientific concepts often treat science like some kind of Pandora's Box — a time bomb just waiting for some unscrupulous lab to churn out man-eating monsters. Whatever the reason, here are movies some scientists absolutely can't stand to watch.

Jurassic Park treats science like it's evil

When paleontologist Steve Brusatte spoke to the BBC on the 25th anniversary of Jurassic Park's release, he revealed a number of aspects of the franchise that don't jive with actual history. Among other things, he pointed out that most of the dinosaurs featured in the film are from the Cretaceous period rather than the Jurassic, that real Velociraptors were about the size of miniature poodles, and that T-Rex eyesight was more than adequate to spot stationary prey.

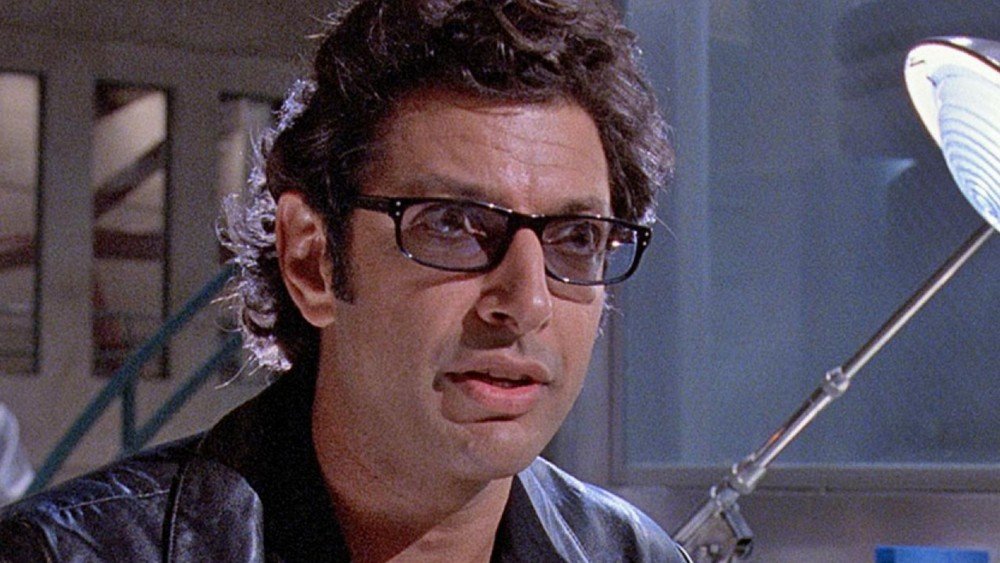

But it isn't just inconsistencies that bother scientists when it comes to Jurassic Park. It's the idea that the story's violence is proof that science is some kind of villain. The theme of "science as the bad guy" is most often expressed through mathematician Ian Malcolm (Jeff Goldblum), who browbeats John Hammond (Richard Attenborough) for even thinking of cloning dinosaurs, saying his scientists were "so preoccupied with whether or not they could, that they didn't stop to think if they should." At one point, he compares scientific discovery to rape, saying, "What's so great about discovery? It's a violent, penetrative act that scars what it explores. What you call discovery, I call the rape of the natural world."

While, sure, none of the death in the film would've happened without someone coming up with a way to clone the reptiles, there's a strong argument to be made that the real culprit in the film isn't scientific discovery but the greed that transforms that discovery into a theme park.

Interstellar thinks love works better than science

Christopher Nolan's 2014 space epic Interstellar was largely hailed as one of the film industry's most sincere attempts to stay faithful to the science of science fiction. For example, astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson gave it a thumbs up, and Time's Jeffrey Kruger — author of Apollo 13 upon which the 1995 film was based — wrote that most of the science passed the test in his review. Astronomer Phil Plait went against the grain and slammed the film for narrative and scientific problems, though even he would later go back and say he was wrong about some of the scientific errors he pointed out.

It isn't so much the science of Interstellar that can irk the more science-minded but one of its central themes — that, as Professor Brand (Anne Hathaway) tells Cooper (Matthew McConaughey), love somehow transcends science. She calls love "the one thing we're capable of perceiving, that transcends dimensions of time and space." It's an idea that seems to be confirmed later in the film when it's Cooper's love for his daughter that allows him to travel back in time. Not only is it a pretty unscientific idea, but it comes off as fairly hokey for a Christopher Nolan film.

Prometheus had some really dumb scientists

Like plenty of other sci-fi flicks, 2012's Prometheus has its share of science errors. For example, as Neil deGrasse Tyson tweeted, when Meredith Vickers (Charlize Theron) says the Prometheus ship traveled "half a billion miles from Earth," that distance would keep it well within our solar system — "just past Jupiter" as Tyson puts it. And they don't just get space travel wrong. Phil Plait points out that when Elizabeth Shaw (Noomi Rapace) claims there's a 100% DNA match between humans and the titanic Engineers, that doesn't really make a lot of sense. A 100% DNA match between two humans isn't even possible except in the case of identical twins.

Prometheus' worst sins, however, have more to do with the scientists themselves. In 2012, Forbes talked to five scientists to see if they would act similarly to Prometheus's characters. Some of the plot points the interviewed scientists found most surprising include two archaeologists discovering a severed alien head and stuffing it in a bag before making any kind of recordings or measurements, a geologist walking blindly into a cave even though he had the technology to map it out beforehand, that same geologist getting lost in the cave system even after mapping it out, and a biologist doing absolutely everything he shouldn't do when encountering a new species that's making a "threat display" and getting himself and a colleague killed in the process. In short, the scientists of Prometheus are the dumbest group of scientists ever seen.

Gravity doesn't have many fans in NASA

Alfonso Cuarón's 2013 sci-fi thriller Gravity was a critical darling. The story about Dr. Ryan Stone (Sandra Bullock) as the last surviving member of an orbital mission to repair the Hubble Telescope won seven of the ten Oscars it was nominated for, and it's currently sitting pretty on Rotten Tomatoes with an impressive aggregate score of 96%. But a lot of scientists would disagree with the critics who heaped the accolades upon Gravity, including the ones who work at NASA.

In 2018, BBC made a video featuring women working at NASA talking about their favorite and least favorite space films, and almost all of them agreed that Gravity was one of the worst. "Everything that could go wrong went terribly, terribly wrong," said heat shield analyst Tori Wills, "and that's not exactly the feeling we want everybody to have about this industry." Chief Allison McIntyre pointed out that when she takes off her space suit, Bullock's character is wearing "cute, little underwear" rather than the diaper a real astronaut would be wearing.

While former US astronaut Scott Parazynski told Vulture he enjoyed the film, he saw just as many inaccuracies as the NASA scientists. For example, Dr. Stone travels from the Hubble Telescope to the International Space Station, and from there, she heads to the the Chinese space station, Tiangong. Parazynski says because of their vastly different orbits and altitudes, the three objects are "basically speeding bullets relative to one another," and "it would be physically impossible to get from one place to the other."

Armageddon wasn't right about much

Veteran rockers Aerosmith contributed the original song "I Don't Want to Miss a Thing" to 1998's Armageddon. Whatever Steven Tyler was singing about, it had nothing to do with how scientists felt about the film. Armageddon gets so much about science wrong that a number of urban legends have popped up about it, including that NASA uses the film in its training to make sure recruits can find most of the errors, and that there are exactly 168 scientific inaccuracies in the movie which — since the film is 151 minutes long — would mean more than one science error per minute.

While the number of errors may not be exactly 168, according to astronomer Phil Plait, the number is high enough. Plait first reviewed the asteroid disaster movie on his Bad Astronomy blog in 1998, and three years later, he added a note to let readers know that "hardly a day goes by without someone emailing me about something I missed." We honestly don't have the room to mention all the science errors Plait found, but some of the highlights include the idea of a comet redirecting a Texas-sized asteroid being ludicrous, that the asteroid should've been spherically shaped, and that it should've been spotted by astronomers much earlier than it was. Plus, in order to accomplish the objective of blasting the massive object into two pieces, the heroes would need about a billion more bombs, and oh yeah, drilling 800 feet into the asteroid would never be deep enough, regardless of the bomb's power.

Scientists thought 2012's premise was ludicrous

In the late aughts and early 2010s, a surprising number of people were caught up in theories about a supposed ancient Mayan prophecy that the world would end in 2012. Hollywood made sure to capitalize on those fears with the disaster flick 2012. With an all-star cast that included John Cusack, Woody Harrelson, and Danny Glover, 2012 had the Earth cracking open, skyscrapers toppling, and all kinds of mayhem — all of it caused by solar neutrinos heating the Earth's core to the point that it liquefies and boils.

The science behind 2012 is so weak that NASA officially listed it as the silliest science fiction film of all time. On Scientific American's blog, Philip Yam explains why absolutely nothing in the film could happen in the real world. Simply put, solar neutrinos don't act the way they do in 2012. Neutrinos are subatomic particles that pass through matter without having much interaction with it. The film doesn't bother to explain why or how its bizarre neutrinos end up heating up the Earth's core but regardless, as Yam points out, even if solar neutrinos could act as they do in 2012, they "should have cooked Earth's surface dry" long before they reached the Earth's core.

Independence Day had the least advanced aliens ever

It's probably not a big surprise that there's a lot of "science" in the 1996 blockbuster Independence Day that doesn't hold up. The film was a big, fun alien invasion flick, and it wasn't meant to act as an educational tool. As such, one glaring head-scratching aspect of the film are the huge firestorms caused by the invading aliens, which should've killed many more characters than they do. Another bizarre plot point is the revelation that the bad guys are using Earth's satellites to communicate with one another. Why would beings advanced enough to build a fleet that can travel across galaxies — not to mention being equipped with force fields so powerful they can withstand nuclear blasts — need our technology to communicate with one another?

But probably the biggest, most ridiculous science boo-boo is the manner in which the heroes win the day. David Levinson (Jeff Goldblum) creates a computer virus, which — once he and Captain Hiller (Will Smith) pilot a captured alien vessel to the mothership — he delivers to the enemy fleet, completely disarming their impenetrable force fields. First, how does Levinson, with a couple of hours' worth of work, create a virus that he somehow is confident will interact with alien technology? Second, and more importantly, how are these aliens so vulnerable to a computer virus that it cripples their entire fleet? They can fly through galaxies, but they couldn't find a single 30-day antivirus trial?

The Day After Tomorrow thinks one lone scientist is enough

In 2004's The Day After Tomorrow, the dire warnings of paleoclimatologist Jack Hall (Dennis Quaid) fall on deaf ears. Hall tries to convince world leaders that a massive climate shift is on the way, but most dismiss his concerns. Of course, his predictions prove true, and within a matter of days, the world is thrown into chaos. Massive storms break out all over the world, a tsunami puts most of New York City underwater, and temperatures drop to the point where people are freezing to death on the street.

The cause of these changes is an actual concern to scientists in the real world. In the film, the disasters come about after the ocean currents of the Atlantic Ocean — the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC) — slow down. While the results are extremely exaggerated in The Day After Tomorrow, both in terms of the impact and the speed with which they occur, the slowing of the AMOC is a point of real concern with scientists.

But what's more troubling than any scientific inaccuracies in the film is the notion that the global community is wrong for not immediately responding to the warnings of a lone scientist. Kind of like Superman's dad was the only one who knew Krypton was dying and no one would listen, Jack Hall is portrayed as the lone voice in the wilderness. And that's not how science works. In the real world, if you're the only scientist claiming something is true, it's probably because it isn't.

Waterworld had too much water for scientists

When it comes to films with environmentalist leanings, the 1995 bomb Waterworld isn't subtle. All of the Earth's ice deposits — including icebergs and the polar ice caps — have melted, leaving almost every single inch of land underwater. The ocean has become such a master of humanity's fate that we eventually learn Waterworld's hero, the Mariner (Kevin Costner), was born with webbed feet and gills, presumably an early example of humans adapting to aquatic life. The notion that dry land still exists — something we find out is true at the very end of the film — is treated like a fairy tale by most of Waterworld's characters.

The problem with Waterworld is that it goes way too far in its depiction of a world wracked by climate change. As Kevin Carr pointed out at Film School Rejects, if the polar ice caps were to completely melt, sea levels would rise, and there's a lot that isn't currently underwater that would be submerged. But there isn't enough ice on Earth to create the almost completely underwater world of Waterworld. In the beginning of the film, for example, we see the Mariner scavenging in the submerged city of Denver, Colorado, but if every piece of ice on Earth were to melt into the ocean, the sea would never get close to Denver. Obviously, an entire world of ocean is a lot more dramatic than simply saying "there's way more ocean than there used to be," but that doesn't make it any more scientifically accurate.

Lucy didn't know much about how brains work

Luc Besson's 2014 sic-fi/action flick Lucy is based on an interesting notion. It's one of a number of fictions culled from the idea that humans only use 10% of their brains. Lucy poses the question of what would happen if we could access that missing 90%? In the case of Lucy's titular hero, played by Scarlett Johansson, it gives her access to unbelievable super powers.

Here's the thing, though. That thing about humans only using 10% of our brains? Yeah, that's not true. In 2008, Robynne Boyd looked into the myth for Scientific American and found the evidence to show that humans use their entire brain is overwhelming. While there may be times during the day — such as when a person is resting — when a person may not use as much of their brain as others, imaging technology has shown that most of the brain's regions "are continually active over a 24-hour period."

So, if you were hoping on getting super powers through deeper brain access, we're sorry to disappoint. But you never know. Maybe that radioactive spider bite will come through one of these days.