Bizarre Storyline Decisions Made In Sci-Fi Movies

At its best, science fiction is a playground for the imagination, where storytellers can bend the laws of reality to open up new possibilities for adventure, horror, or even comedy. Sci-fi stories should be allowed to be weird, to take risks and experiment with new ideas, and plenty of films in the genre begin with the promise of something strange and then deliver on that promise, for better or worse. Audiences walk into movies like Her, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, or Annihilation with the foreknowledge that they're in for something different, and that they should expect the story to go in some unanticipated directions. But every so often, a sci-fi film that seems fairly conventional will contain a twist that provokes a raised eyebrow or worse. Sometimes a storyteller wins us back and justifies their wild ideas — but often, we find ourselves looking back on a work, seeing the possibilities laid out in hindsight, and wondering "Why this?" With all that in mind, here's a look back at some of the most bizarre storyline decisions made in sci-fi movies.

The underground aliens of Spielberg's War of the Worlds

H.G. Wells' classic novel The War of the Worlds is widely considered the prototypical "alien invasion" story. Its imagery of otherworldly spacecraft descending from the skies to lay waste to human civilizations has been reproduced onscreen multiple times, both in direct adaptations and in derivative works like Independence Day. So it made sense that, when director Steven Spielberg decided to mount his own film adaptation in the early 2000s, he would want to make some changes to differentiate his take on the familiar tale.

One such change was to show the alien invasion emerge from beneath the Earth, rather than from above. In Spielberg's 2005 War of the Worlds, bystanders witness a massive tripodal tank rise from beneath the city streets to massacre the populace. This implies that the craft was buried for centuries and suddenly awakened (or manned, via teleportation), and that the invasion of Earth has been in the works for at least that long.

While this sidesteps a cliché, the premise that the alien invasion had tools on our planet for centuries makes the ending a bit puzzling, as the invading aliens are felled — as in the novel — by Earth's microscopic pathogens, to which the aliens have no immunity. The idea that spacefaring conquerers would be ignorant to dangerous germs is already harder to swallow for 21st century viewers than for 19th century readers, but this added twist makes it even more implausible.

X-Men: First Class kills an unkillable mutant

In 2011, director Matthew Vaughn unexpectedly revived the ailing X-Men film franchise with a prequel installment about Professor Charles Xavier and Erik "Magneto" Lehnsherr assembling the first X-Men team in 1962. While most of the original team from the comics had already been used in the previous films, all set decades later, the film's screenwriters still had a massive bench of characters from X-Men mythology to introduce to the film continuity. They ultimately assembled a cast from throughout the comic's history, ranging from the obvious (Beast) to the obscure (Riptide).

But one of the mutants introduced in First Class doesn't live long enough to do much of anything, introduced and killed within a few screen minutes during the film's second act, and it's the one who makes the least logical sense to die. Darwin — whose body adapts to survive threats and hazardous environments — meets his match in only his third scene, when his body can't handle ingesting a burst of chaotic energy. It's almost expected for a Hollywood action movie to kill off at least one member of an ensemble at the midpoint in order to raise the stakes or motivate the protagonists, but given the literally hundreds of characters provided by the X-Men license, choosing to make a sacrificial lamb out of a guy whose thing is "not dying" doesn't make much sense. It also leaves the teammate with the most visually interesting power set out of the film's climax.

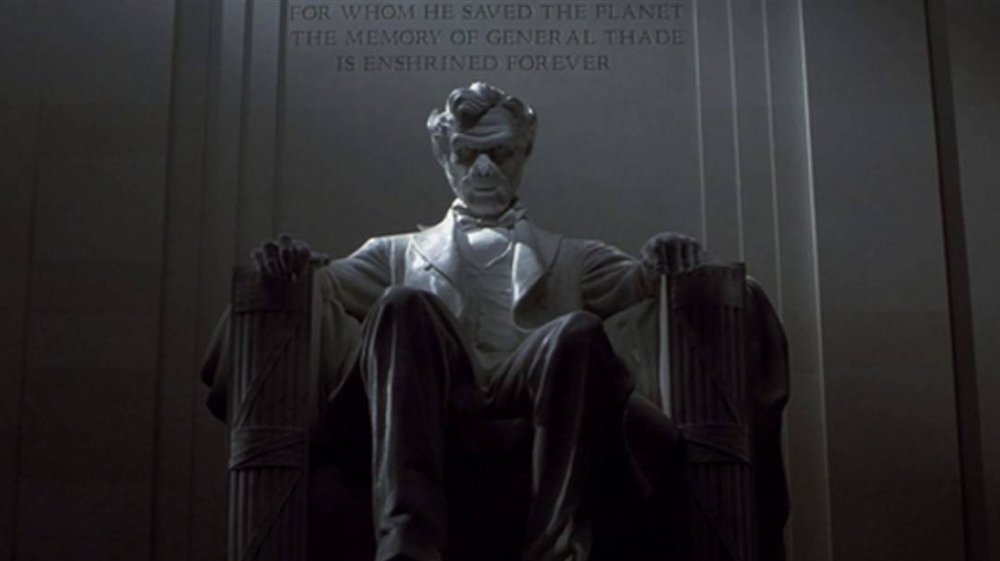

Tim Burton's Ape Lincoln

The image of astronaut George Taylor discovering the remains of the Statue of Liberty on a post-apocalyptic beachfront at the end of the 1968 classic Planet of the Apes is one of the most iconic images in cinema. While shocking at the time of its release, the twist that Planet of the Apes is actually set on our own war-torn Earth rather than some alien world is now a "surprise" to very few. This presented a problem for the producers of the 2001 remake helmed by Tim Burton, who hoped to give the audience a comparable shock. After a multitude of scripts came and went, the final product settled on a twist that befuddled audiences worldwide.

The 2001 Apes centers around a complicated time travel plot, wherein the planet Ashlar is populated by the descendants of human astronauts and their trained ape companions thousands of years before the start of the film (but also afterwards). This itself might be an interesting, if predictable twist. But in an effort to truly confound viewers, the film closes with a second time-travel reveal, that the villainous ape General Thade has beaten human Leo Davidson back to Earth by years and already conquered the planet. The film closes on the laughable image of the Lincoln Memorial altered to feature actor Tim Roth's ape-ified face. This twist frustrated audiences so much that the DVD release included an insert explaining the film's convoluted timeline.

Everyone's related in Star Wars

The Star Wars galaxy is sprawling in scale and teeming with sentient life, but the film saga has repeatedly doubled down on the idea that the entire universe revolves around a single family. In the original Star Wars, Luke Skywalker is a farm boy who learns that his father was a member of a now-mythical order of knights, and receives training from his father's old friend to follow in his footsteps. But after the shocking reveal that Luke's father Anakin and his enemy Darth Vader are in one and the same in The Empire Strikes Back, the saga becomes preoccupied with this bloodline to the extent that Disney eventually rebranded the nine core films as the Skywalker Saga.

Return of the Jedi reveals that Leia Organa, too, is a Skywalker, despite no foreshadowing from previous films. Revenge of the Sith implies that Anakin himself was created due to Emperor Palpatine and Darth Plagueis' experiments with the Force, essentially making him one of Anakin's parents. The Force Awakens introduces the villainous Kylo Ren, son of Leia Organa, whose heroic counterpart, Rey, is determined to be the granddaughter of Palpatine in the out-of-nowhere twist of The Rise of Skywalker. And given Palpatine's apparent role in Anakin's conception, this means Rey is sort of Kylo Ren's aunt.

Given the apparently improvisational, film-by-film plotting of both the original and sequel trilogies, it seems as if the only golden rule in writing Star Wars is "When in doubt, they're related!"

The Aliens were here all along in AvP

Alien vs. Predator was a hotly anticipated blockbuster, years in the making. Sparked by a short comics story in 1989 and an Alien easter egg in the 1990 feature film Predator 2, AvP grew into its own franchise of comic books and video games over the course of the '90s. Most of these works are set far from Earth and/or in the distant future, and there's a good reason for that.

Throughout the Alien film series, heroine Ellen Ripley attempts not only to survive her repeated encounters with the terrifying alien beasts, but to prevent industrial and military interests from bringing one of them to Earth. Once even one single alien makes it to Earth, the jig is up. Xenomorphs cannot be contained, however hard you try.

AvP comics and games tended to respect this idea, but when the long-gestating film finally burst to life, it was set on Earth in the contemporary 2004. The film borrows the conceit of the original comics miniseries — that fighting a cultivated alien hoard is a rite of passage for Predators — but it adds the wrinkle that Predators have been performing these ritual hunts on Earth for thousands of years, keeping xenomorph queens in captivity all along. Given that most of the film takes place inside a labyrinthine Predator structure anyway, setting the film on Earth served little purpose but to drain tension from not just this, but other films in the adjacent series.

I Am Legend blows up its ending

In this 2007 adaptation of Richard Matheson's novella, Lt. Col. Roger Neville (Will Smith) is a man alone on a mission to cure the virus that has wiped out most of humanity and turned the rest into vampiric beasts called Dark Seekers. Seeds are planted throughout the film to indicate that the Dark Seekers may be more than mindless monsters, that they may have thoughts and attachments like they once had as human beings. But rather than pay that off, the film ends with Neville rescuing some fellow humans by killing himself and his Dark Seeker foes with a grenade.

If this seems like it comes out of nowhere, that's because it does — the film originally ended with Neville confronting the immorality of abducting and performing deadly experiments upon the Dark Seekers, and understanding that have every right to see him as a monster. He returns his final Dark Seeker test subject to her family and apologizes for his actions, and the creatures leave Neville in peace. While it more closely mirrors the ending of the source material, test audiences hated it, and the studio called for a more uplifting ending in which Neville successfully obtains the cure from his final test subject and the Dark Seekers are plainly irredeemable.

The theatrical ending may hand humankind the win, but the alternate version better fulfills the potential of the story, and performs the best function of sci-fi: encouraging the audience to challenge their preconceptions.

Lucy fulfills average human brain potential

Most Hollywood sci-fi films are "soft sci-fi," meaning that they play fast and loose with plausible science in favor of fun "what ifs" with just enough lip service paid to realism to keep them from being classified as "fantasy." This is a relatively harmless practice, but when a film reinforces popular but patently untrue pseudoscience, that's another story.

In Luc Besson's Lucy, Scarlett Johanssen's character accidentally ingests an illegal drug that allows her to utilize more than the ten percent of the brain capacity supposedly available to other human beings. As she gradually unlocks her entire brain, she not only achieves greater memory and faster computational speed, but she gains control over time and space and eventually transcends our physical reality altogether. Lucy features cool action and creative visuals. But there's a problem: scientists know exactly what happens when a person uses their entire brain, because you're doing it right now.

As Scientific American will attest, the human brain is an extremely busy machine, and people use almost every part of it nearly all the time. It's theorized that the Ten Percent Myth may have originated with a misinterpretation of a 19th century study that got traction in the self-help community, not the scientific community. Centering a film around the Ten Percent Myth in 2014 is as weird as basing one around phrenology. And given that about 65% of Americans believe the Ten Percent Myth, it might actually be worse.

George Clooney's ex is a 12-year-old in Tomorrowland

The execution is better than it sounds. In The Iron Giant director Brad Bird's live-action debut Tomorrowland, George Clooney portrays Frank Walker, a middle-aged and washed-up genius who once lived in the titular place, an extra-dimensional laboratory for unfettered scientific research. He is drawn back into adventure by Athena (Raffey Cassidy), the recruiter who first brought Frank to Tomorrowland 50 years earlier. But since she's a robot (or an "animatronic," in the film's parlance), she still appears to be a 12-year-old girl. The rapport between Frank and Athena is akin to bickering divorcés, a pair who have feelings for each other but are separated by some very irreconcilable differences. Athena ultimately sacrifices her life for Frank's, hoping that he might live to help foster the optimistic future in which they once both believed.

While definitely a weird, "only-in-sci-fi" concept, the dynamic between Frank and Athena is only pulled off thanks to some very skilled, very very careful acting, which manages to convey the familiarity of peers and the emotional intimacy of partners while staying out of the danger zone of inappropriate sexual tension that would have rendered the film unwatchable. This casting, easily the weirdest choice in Tomorrowland, ended up being the only memorable part of an otherwise unremarkable film.

Spock's brother hunts God in Star Trek V

1989's Star Trek V: The Final Frontier might be the most infamously bad film in the long-running franchise (though not the only bad one). It's an easy target, given that it was conceived and directed by star William Shatner, who only got the opportunity because co-star Leonard Nimoy had helmed the previous two films and the pair had a Favored Nations clause in their contracts since the 1960s. The production was crunched, the effects are shoddy, and Spock wears a pair of rocket boots. There's a lot to laugh at.

The Final Frontier has issues to spare, but it stems from a story that's pretty out there, albeit admittedly not that much weirder than some classic Trek episodes. Spock has a long-lost half-brother, an evangelist who brainwashes the crew of the Enterprise (minus the core trio of Kirk, Spock, and McCoy) and leads them on a quest to the forbidden center of the galaxy, where he expects to find God himself. Instead, they find an imposter, a non-corporeal being who attempts to con his way out of exile.

What's truly bizarre is that this is the compromised vision of Shatner's Star Trek V. His original pitch set the climax in literal Hell, where Kirk and company would be up against the literal Devil. As poorly as The Final Frontier went over with critics and fans, it's hard to calculate how much worse the backlash might have been if Shatner had made the film he intended.

The Predator wants to harvest autism

Writer/Director Shane Black has built his career at the nexus of offbeat and bankable, entrusted with blockbuster franchise tentpoles like Iron Man 3 while also maintaining a reputation for a distinctive style. A viewer familiar with Black's work knows to go into his movies expecting the unexpected. But the final twist in 2018's The Predator likely threw even the best-prepared filmgoer for a loop.

In The Predator, a bigger and deadlier alien hunter arrives on Earth with the goal of collecting the DNA of our planet's deadliest creatures to mix with his own. (This being a Predator movie, the DNA samples are obtained not with a cheek swab, but instead by ripping the subjects' spines out.) As usual for the series, The Predator is centered around soldiers, trained fighters who would be the expected targets of the Predator's hunt. But the Predator isn't interested in rugged U.S. Army sniper Quinn McKenna, the rest of his ragtag unit of troubled soldiers, or even the brilliant evolutionary biologist fighting alongside them. Instead, the Predator's ultimate target is Quinn's preteen son Rory, a linguistic genius who has a form of autism and is therefore "the next step on the evolutionary ladder."

The Predator's depiction of autism has not won it many fans among film critics with autism, as it relies upon the tired and dehumanizing trope of the autistic savant. As Salon's Matthew Roszha puts it, "If a movie perpetuates a stereotype with the best intentions, does that make it any less problematic?"