Unpopular Opinions About Star Trek That Raise Good Points

There are few pop culture phenomena as massive as Star Trek, which launched its eighth and ninth television series in 2020 and, between television episodes and feature films, is approaching its 800th production. Likewise, there are few fanbases as rabid, or as varied in their opinions. Star Trek is founded on the principle of Infinite Diversity in Infinite Combinations, and so it's only logical that its fans should be splintered as to which is the best series, the best film, and so on. If you gather a dozen Trekkies in a room, you'll get a dozen opinions, and that's ultimately a good thing.

Fan opinions are particularly fractured around the most recent entries in the franchise — Discovery, Picard, and Lower Decks — and no consensus yet exists to be challenged. But when it comes to older series, there are some takes that have been around long enough to become (dare we use the word) canonized and could bear some re-examining. Star Trek is about exploring new ideas and challenging preconceptions, so we hope you'll keep an open mind as we present a few perspectives that you may have previously dismissed or never considered.

Will these opinions, too, need a second look in a few years' time? As Q says, "the trial never ends..."

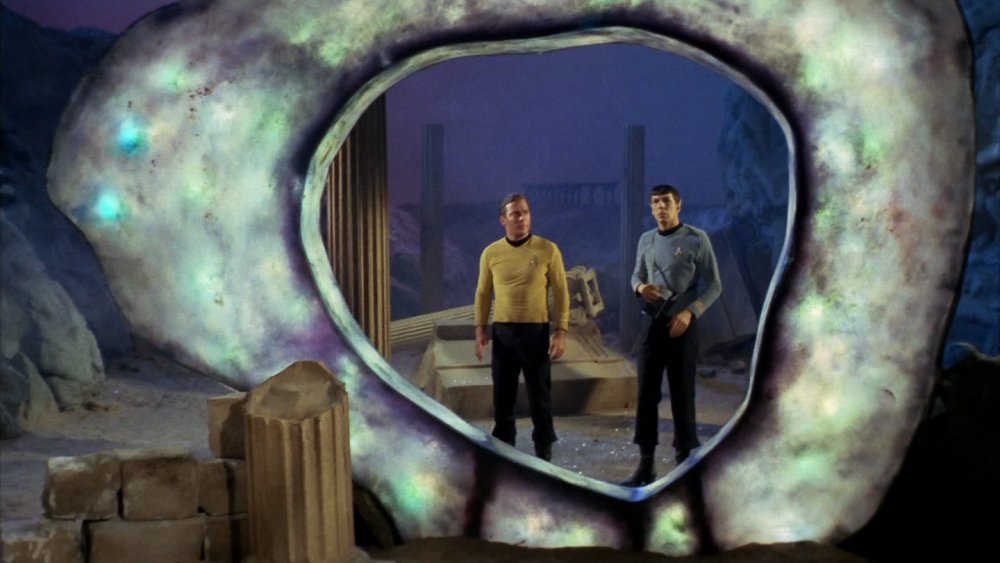

The City on the Edge of Forever isn't the best episode

When surfing the internet for countdowns of the best episode of Star Trek: The Original Series, or even the franchise as a whole, there's one episode that appears at number one on list after list after list. "The City on the Edge of Forever" was penned by sci-fi author Harlan Ellison and then heavily rewritten by Dorothy "D.C." Fontana, and won the series a Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation. In this beloved episode, Kirk and Spock are hurled back in time to 1930s New York, where they must prevent a drug-addled Dr. McCoy from saving the life of visionary social worker Edith Keeler (Joan Collins), whose death is critical to history. The tragedy is compounded when Kirk falls deeply in love with Keeler.

No one's denying that "The City on the Edge of Forever" is great television, but it's missing the element that Star Trek is most famous for — using sci-fi to dress up and comment on a social issue. While it's a well-written, well-acted, well-produced hour of TV, it doesn't contain any message that applies to the viewer. That doesn't mean it can't be your favorite episode, but accepting this answer as a foregone conclusion does a disservice to Trek, and once "City on the Edge" is off the table, the conversation over which is the best episode of Star Trek gets a lot more interesting. (Paging "Balance of Terror" and "The Devil in the Dark.")

The Prime Directive is an unethical policy

Starfleet's non-interference doctrine, known as the Prime Directive, is held up as their highest law. Its actual text has never been revealed (which, conveniently, allows it to be subtly redefined to serve a particular story), but the basics are as follows: Starfleet officers may not reveal the existence of interstellar life to any world that hasn't yet developed warp travel. The Prime Directive is intended to protect cultures from being exploited or derailed by a technologically superior force, which has been the source of centuries of tragedy in Earth's history.

In The Original Series, this is nearly always how the Prime Directive is enforced, as a check against anyone in Starfleet who may try to model another culture after their own, support one faction in an internal conflict, or exploit their resources for their personal or political gain. Captain Kirk would cast the Prime Directive aside if non-interference would mean certain death for another culture, as contamination is certainly less harmful than annihilation.

But beginning with The Next Generation and on through subsequent spinoffs, the Prime Directive is elevated to a fatalistic dogma, where Captains Picard, Janeway, and Archer each employ it to justify inaction in the face of species' certain and total extinction, as if to do so would be to meddle in an unknowable "cosmic plan." This interpretation of the Prime Directive is so nakedly evil that it's no wonder protagonists frequently circumvent it.

Star Trek failed its inclusive legacy for years

Star Trek has had a reputation for championing diversity from the very beginning, as creator Gene Roddenberry insisted that the original Enterprise crew reflect a diverse and equitable future for humanity. While not principal roles, the presence of Nichelle Nichols as Lt. Uhura and George Takei as Lt. Sulu were deeply meaningful in an era when people of color were rarely represented on television beyond demeaning stereotypes. Roddenberry liked to tout Star Trek's inclusive vision of the future, and it's remained an important part of the brand's image.

Television eventually caught up with Star Trek in terms of presenting multiracial casts, but as the franchise expanded in the '80s and '90s, Star Trek was shy about expanding the scope of its inclusive future any further, particularly under the stewardship of Executive Producer Rick Berman, who oversaw all Star Trek productions from 1991 through 2005. Berman allegedly vetoed multiple attempts to introduce queer characters to Star Trek, allowing sexuality to be explored only through the veil and plausible deniability of sci-fi. Prequel series Enterprise, which premiered in 2001, even took a step backwards in inclusivity, habitually casting men in nearly all non-romantic guest roles.

The most recent wave of Trek series has shown great improvement in this department, more diverse both onscreen and behind the scenes than ever before. But if today's shows truly had the boldness of the original, fans wouldn't still be waiting for the first trans Star Trek character.

Data always had emotions

One of the ongoing character threads on The Next Generation is Lt. Commander Data's quest to become "more human." An android built in the image of his human creator, Data believes that while he is more physically and intellectually capable than any human, he will not be complete until he experiences real human feelings, as his positronic brain is incapable of emotion. But here's the thing — Data does have feelings, they're simply not as obvious as those of the people around him.

Data says he lacks feeling, but his actions say otherwise. He is driven to pursue truth and to oppose injustice, and is endlessly curious. He has a sense of fun and whimsy, dressing up with Geordi to play Sherlock Holmes in the holodeck. Data is deeply attached to his friends, experiencing concern for comrades in danger and grief for those who are lost, such as Lt. Tasha Yar. Here's how Data describes his experience of friendship to Tasha's sister, Ishara, in the episode "Legacy:"

"As I experience certain sensory input patterns, my mental pathways become accustomed to them. The inputs eventually are anticipated, and even missed when absent."

Data can monitor and analyze his responses to stimuli in a mechanical, mathematical way, but that doesn't make them any less real than our own feelings. Perhaps someone early in his life — some cyberneticist or Academy instructor — told him that he had no emotions, and he believed them. In fact, he's not deficient, just different.

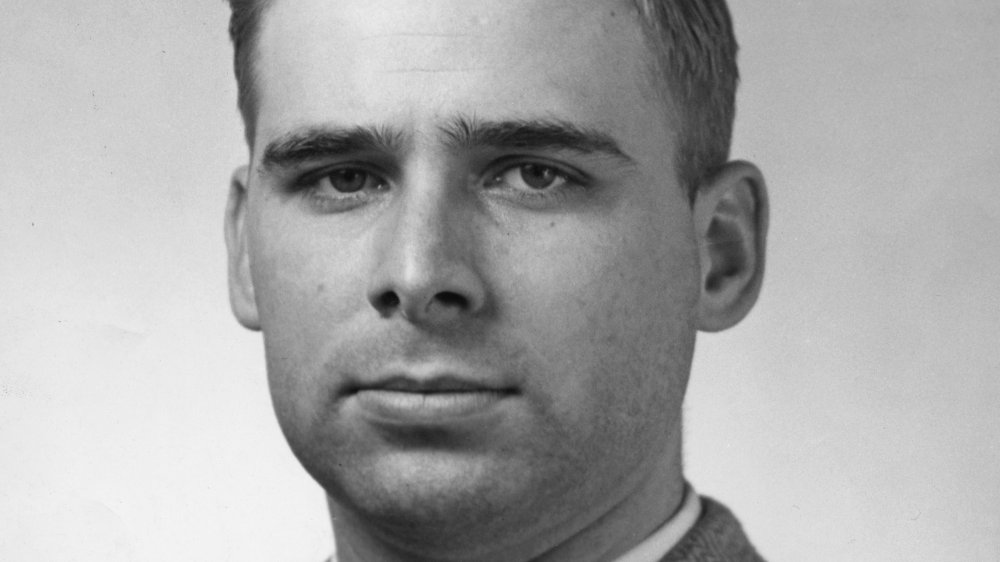

Gene Roddenberry gets too much credit

It's inarguable that Star Trek would not exist without creator Gene Roddenberry. Roddenberry provided the blueprint for Trek and fostered the cult following around it (and around himself). But as more has been revealed about the backstage drama of the franchise, it has become clear that Roddenberry has received far too much credit for Star Trek's enduring quality.

In recent years, much of the success of The Original Series has been reattributed to head writer Gene L. Coon. In The Fifty-Year Mission: The Unauthorized, Uncensored Oral History of Star Trek by Edward Gross and Mark A. Altman, multiple members of the production sing Coon's praises while voicing frustration at Roddenberry's alternating micromanagement and absenteeism. The book also details Roddenberry's awful drafts of The Motion Picture, and allegations that he attempted to sabotage the now-beloved Wrath of Khan after Paramount stripped him of creative control over the film series.

While Roddenberry did return to create the hit spinoff The Next Generation, his declining health meant that he had far less influence than producers Rick Berman, Maurice Hurley, and Michael Piller, or even his own lawyer Leonard Maizlish. Deep Space Nine, arguably the best Star Trek series, was created entirely without him.

One need only look to Roddenberry's failed works outside of Trek to realize that he was not a genius, but a writer with one solid pitch and a knack for self-promotion. Star Trek was his baby, but it took a village to raise it.

Star Trek's greatest hero is Rom

The main characters on Star Trek are typically Starfleet officers who, by virtue of the post-greed, post-bigotry utopia in which they are raised, are just better than we are. As such, heroism is always expected from them, and there's only so far they can grow or develop.

Deep Space Nine broke from this mold. Set on a non-Federation space station, DS9 features a variety of characters who don't have the benefit of being born in paradise, and have a lot more growing to do. Take Kira Nerys, who spends her youth as a self-described terrorist resisting an occupying force and learns how to live with and grow beyond her trauma over the course of seven seasons.

But consider the unlikely journey of Rom, brother of Ferengi bartender Quark. Rom is a sweet guy with genius potential in engineering who is perceived as worthless by other Ferengi for his lack of killer business instinct. But when his son bucks tradition to join Starfleet, Rom finds a new courage to pursue his own dreams and to help others. He becomes a radical (by Ferengi standards) who unionizes his workplace, saves the station from the Dominion, and is chosen as the leader of a new, more progressive Ferenginar.

Rom is the adult product of a society that's much more like our own than the Federation is, who manages to grow into a Star Trek hero anyway. If he can do it, we can do it.

Neelix is not the worst Voyager character

You won't find a character more universally loathed among Star Trek fans than Neelix, who has attracted Jar Jar Binks levels of scorn since his introduction on Star Trek: Voyager in 1995. Conceived as a kooky alien "outsider" in the vein of Deep Space Nine's Quark, who would bounce between hatching little schemes and commenting on human behavior, Neelix quickly became an intolerable, unfunny attempt at a comic relief character. Unlike his more interesting companion Kes, who was written off the show after three seasons to make room for Seven of Nine, the vastly unpopular Neelix stuck around for the entire seven-year run of Voyager.

Whenever Neelix makes an obligatory supporting appearance in an episode centered around another character, he contributes very little but to deliver some badly written jokes. But stories that actually center on Neelix, that let actor Ethan Phillips play a dramatic role rather than a comedic one, tend to be very compelling. It's in episodes like "Jetrel" and "Mortal Coil" that viewers get a real look at Neelix and see that, behind his goofy persona, he's the saddest man in the Delta Quadrant trying to find some joy and a sense of belonging after having lost everything that ever mattered to him.

Neelix contributes some of Voyager's most groan-worthy moments, there's no denying that. But when the storytellers give him the spotlight, he shines much brighter than fellow regulars Chakotay or Tuvok, who never manage to be anything but boring.

Jolene Blalock gives one of Star Trek's best performances

When Enterprise debuted in 2001, it was easy for fans to have a cynical prejudice against the character of T'Pol, played by Jolene Blalock. Like Marina Sirtis and Jeri Ryan before her, Blalock was poured into a tight catsuit and her character was repeatedly thrown into compromising and sexually suggestive scenarios. It was part of the Star Trek formula by this point for one female member of the cast to bear the burden of drawing in the network-mandated, advertiser-approved teenage male gaze with some grossly pandering sexuality, with all other character considerations secondary. For the show's painful early seasons, T'Pol was thinly written and Blalock was given little to work with, especially considering that she was, on paper, the show's second lead.

But when Enterprise's third year featured a dark and heavy season-long arc in which the cast finally got to do some heavy lifting, no performer did more with what they were given than Jolene Blalock. Over the course of the arc, T'Pol struggles with the high stakes of the mission while secretly experimenting with a chemical that removes some of her emotional inhibitions. As T'Pol copes with her changing feelings, her fear of going mad in a strange region of space, and her "illogical" romantic interest in shipmate "Trip" Tucker, Blalock's performance is genuinely compelling. Her work in the episodes "Twilight," "Similitude," and "Damage" hold up as some of the best acting in the franchise.

Every Star Trek captain should probably be in prison

Starfleet captains are meant to be the finest examples of humanity, leaders who strive for peace and knowledge and defend the rights of all beings. But nobody's perfect. In fact, in nearly every Star Trek incarnation, the person in the center seat does something for which they should not only lose their job, but spend some time in jail.

Captain Kirk disobeys orders and then steals and destroys the USS Enterprise in Star Trek III: The Search for Spock, but he ends up walking away with a slap on the wrist thanks to his saving the day in the sequel. Voyager's Captain Janeway orders Tuvix, an individual created in a transporter accident that fused crewmen Tuvok and Neelix, to be split back into his "parents" against his will, an act that Tuvix refers to as a murder. Captain Archer of Enterprise stoops to torture and piracy during his desperate mission in the Delphic Expanse. Captain Sisko of Deep Space Nine violates a handful of Geneva Conventions himself — he deploys a chemical weapon on a populated planet in order to win a battle of wills with a Maquis rebel, and later fabricates evidence to draw the Romulans into a war against the Dominion, becoming an accessory to murder in the process.

We still love them, but if these characters were guest stars instead of regulars, they'd be closing out these stories writing prison diaries instead of Captain's Logs.

Move Along Home is a good episode, actually

Star Trek can be serious business. Fans like that Trek can be a philosophy classroom, a thought laboratory with high stakes and drama. But there's also been an inherent silliness to Trek since the days of "The Trouble with Tribbles." The universe is vast and full of challenges, and not all of those challenges should be grave, life-and-death affairs. Space should also be allowed to be weird. As Jean-Luc Picard says in another goofy episode, "sometimes you just have to bow to the absurd."

"Move Along Home," an early entry in Deep Space Nine's first season, is often the target of ridicule (just open a new tab and google "Worst DS9 Episode" and see what comes up) and in fairness, it's pretty ridiculous. In this episode, Commander Sisko and company greet the Wadi, the station's first official visitors from the Gamma Quadrant, who as it happens aren't interested in signing treaties or trade agreements — they're here to gamble. Soon, Sisko, Bashir, Dax, and Kira find themselves in a mysterious realm of dangerous puzzles that appear life-threatening but are actually just part of the Wadi gamers' harmless fun.

And that's what "Move Along Home" is — harmless fun. It's bizarre Trek in the classic tradition, the most like an Original Series episode in all of Deep Space Nine, and shouldn't be considered the worst episode of a series that also includes the truly offensive "Profit and Lace."

Star Trek canon has always been broken

Since Star Trek: Discovery debuted in 2017, a vocal subset of fans have been incensed by the dramatically updated production design, particularly given that the series takes place only a decade before the cherished Kirk Era. There's simply no way to reconcile the look and technology of Discovery with that of The Original Series. This, along with some retroactive continuity employed in its story, means that this new series commits what is, for some Trekkies, an unforgivable sin: breaking from "canon."

But here's the thing: Star Trek's internal continuity has never been carved in stone. Within The Original Series, there is inconsistency regarding the name and nature of the government that Starfleet represents, Spock's powers and how they work, and even what century it is. The Next Generation and its spinoffs place great importance upon Data being the only known artificial life form, despite Kirk having personally met (and killed) several on TOS. The Klingons have changed appearance multiple times before Discovery's overhaul, and no two series seem to agree on how the Federation's economy works. These are just a few examples — there are entire websites dedicated to tracking revisions and inconsistencies in Star Trek canon.

There's nothing wrong with not liking the new Star Trek series, or choosing not to watch them. But to dismiss them as "Not Star Trek" because they look different or contradict earlier works also requires that nearly all Star Trek be struck from the record.