The Backstory Of The Lord Of The Rings Elves Explained

Elves are an interesting construct of the fantasy world. The term can refer to very different beings depending on the story in question. Elves from the Elder Scrolls or Fae from Carnival Row aren't the same as Tinkerbell or the indentured servants in Santa's workshop. The point is, while the term "elf" can indicate a few generally accepted attributes, Elves vary dramatically from one legendarium to the next.

Case in point: J.R.R. Tolkien's Elves. Among the first magical creations of modern fantasy, the Elves of Middle-earth are heavily involved in the plots of The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit and are the central characters in The Silmarillion. In other words, without them, his entire world wouldn't exist. The man explains in the foreword to The Fellowship of the Ring that the reason he started writing The Silmarillion was "to provide the necessary background of 'history' for Elvish tongues." Obviously, the author's ambitions grew beyond that simple goal, and in the process, created one of the most fascinating races in modern fantasy. With that in mind, here's the backstory of the Lord of the Rings Elves explained.

Setting the Stage

If you want to understand the backstory of the Elves, it helps to start with a quick rundown on the world that they walked into. The history of Middle-earth goes way back, tens of thousands of years before the Elves ever set foot on the continent. In these early days, Arda — that is, the world — is created by Ilúvatar. His servants, the angelic Valar, enter with the task to shape and protect it from the Dark Lord Morgoth (Sauron's original master).

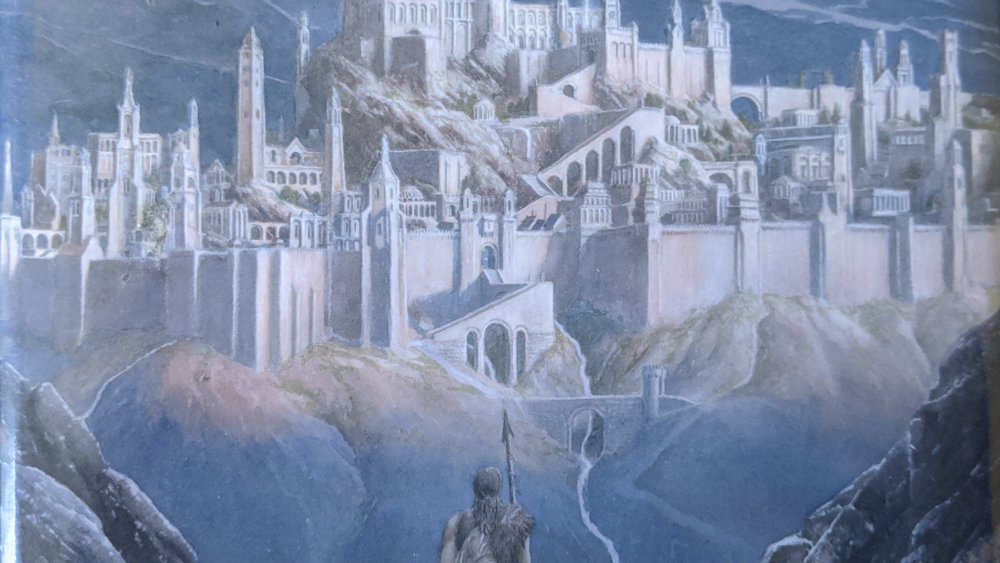

Eventually, ongoing, world-shattering wars with Morgoth lead the good guys to let the Dark Lord run loose on the central continent of Middle-earth while they withdraw west, across the sea. Here they build a heavenly new home in the heart of a continent referred to thereafter as the Blessed Realm — we're talking about the same place Frodo and Bilbo head for at the end of The Return of the King.

While this relocation works for the moment, critically, the Valar also know that, sooner or later, Ilúvatar is going to send an unknown but important group of peoples he refers to as his "Children" into the world to inhabit it, and they must be prepared to receive them. With that in mind, one of the Valar, named Varda, creates bright new stars and hangs them in the sky to light the path for these mysterious "Children" when they arrive.

Elves, the Firstborn Children of Ilúvatar

The concept of "the Children" of Ilúvatar comes up a lot in The Silmarillion. In essence, these Children are unique creations with souls of their own. In other words, they're peers — albeit dramatically smaller and weaker peers — of their angelic brethren, not to be shaped or molded as a part of the larger creation, but rather to cohabitate in the world with them.

While the Valar are told that these Children will eventually come into existence, they aren't told the time or place of their arrival. The Elves are the first of the Children to arrive, giving them the name of the Firstborn or the Elder Children. They're followed, thousands of years later, by men, also known as the Followers or the Aftercomers. When he creates them, Ilúvatar declares that the Elves, in particular, will be "the fairest of all earthly creatures... and they shall have the greater bliss in this world."

As they arrive, each of the Children become focal points in the struggle between Morgoth and the Valar. Some stay true to their Creator while others, both Elves and men, are corrupted and end up fighting against their brethren.

The Elves awake

As soon as Varda finishes creating the new stars for the Firstborn, they "awake" out in the vastness of Middle-earth next to a lake cleverly called Cuiviénen, or "the Water of Awakening." The first things that these Elves see and hear are the stars and flowing water, and they're instantly entranced by both sight and sound.

Over time, they create language and call themselves the Quendi, meaning beings that speak with voices. Morgoth is aware of these newcomers first, and he causes some mischief (more on that in a minute), but eventually, one of the Valar arrives and names the Elves the Eldar, meaning the "people of the stars."

The Elves spend an undesignated, but clearly lengthy, amount of time hanging out by the Lake of Awakening, enjoying the running water and the bright stars overhead. However, the Dark Lord is still at large, and the Valar finally decide that something must be done to protect the Firstborn.

Orcs and Elves: a family feud?

Before we get too far into the history of the Elves, it's worth taking a quick detour to talk about a group of people that are rumored to be some of their direct relatives: the orcs. The orcs and goblins of Tolkien's world never receive too much attention, and multiple versions of their origins are given in different places. Peter Jackson even took the liberty in his adaptation of assuming that the Uruk Hai were born in some sort of festering mud pit, which — what the heck?

The most common version of the genesis of the orcs, though, comes here at the beginning of elven history. As they wake up and chill out around this lake in the darkness under the stars, Morgoth is the first to find them — which is obviously not good news for these poor creatures that don't even know who they are yet.

In The Silmarillion, it explains that Morgoth "sent shadows and evil spirits to spy upon [the Elves] and waylay them. So it came to pass... that if any of the Elves strayed far abroad, alone or few together, they would often vanish, and never return." It then adds that the Elves believe that those who were captured were put in Morgoth's prisons where they were corrupted and enslaved by "slow arts of cruelty." Eventually, this enables Morgoth to "breed the hideous race of the Orcs in envy and mockery of the Elves, of whom they were afterwards the bitterest foes."

The Elves are called westward

With the Elves awake and wandering through Middle-earth and Morgoth prowling about, it quickly becomes apparent that something must be done to protect the Elder Children. The Valar hold a council and decide that they should stop their enemy dead in his tracks. This leads to an epic slugfest between the Valar and Morgoth in which the Dark Lord is overthrown and captured. After this, the Valar summon the Elves to come live with them in the Blessed Realm.

This invitation is accepted by some Elves but rejected by others who prefer life under the stars and in the wide open spaces. This leads to the first split between Elves, as most of them begin to migrate west while a minority stay put in their original homeland.

As the migrating Elves travel toward their new home, they begin to shrink as chunks of Elves peel off for various reasons. However, a large core of the nomads eventually reach the westward coast and are transported across the sea on an island, officially relocating to the Blessed Realm in the process.

Wait, who's who?

It's this period of migrations and shuffling around that creates the most confusion with Tolkien's Elves. As groups stay and go, split off, or dawdle on the road, it creates several different "branches" of the Elves. Trying to sort through all of the information can feel totally overwhelming, but we've tried to boil things down to a few important names and events.

As already mentioned, the Elves are initially split when most of them choose to migrate westward. The migrants are further split into three sub-groups, the first two of which — called the Vanyar and the Noldor — reach the Blessed Realm intact. The third group, called the Teleri, is larger but it loses many members along the way. Some are left behind around the Misty Mountains and become known as the Nandor — the branch of Elves that eventually found both Lothlorien and the Woodland Realm in Mirkwood. Most of the rest of this third group ends up settling down on the western coast of Middle-earth and becomes known as the Sindar.

So, when all's said and done, you have the Elves who never migrated, various sub-groups that settled along the way, and the two groups that made it to the Blessed Realm. Got all that? Fortunately, it's at this point that the family trees start to get left behind and the action picks up.

The Noldor return to Middle-earth

After the great Elvish migration, a long period of time passes in which Morgoth is imprisoned and the Elves thrive. However, after ages have passed, the Dark Lord is pardoned after pretending to have changed his ways. Released from prison, Morgoth begins to subtly corrupt the hearts of the Elves in the Blessed Realm — especially the Noldor. One of these, named Fëanor, creates three incredible jewels, known as the Silmarils. Morgoth becomes particularly fixated on this powerful, aggressive Elven lord.

When a chance comes, Morgoth attacks the Blessed Realm with his ally, the monstrous spider-spirit Ungoliant. In this attack, he destroys the continent's light source — two enormous, glowing trees — and then steals the Silmarils and escapes. Furious at the treacherous act and persuaded (by Morgoth, no less) that the Valar can't protect his people, Fëanor convinces most of the Noldor Elves to leave the Blessed Realm and head back to Middle-earth to get revenge and reclaim their jewels.

The Elves and the First Age

As the Elves arrive back in Middle-earth, the Sun and Moon officially rise for the first time and the First Age begins. This is the age that The Silmarillion primarily focuses on, and it primarily follows the Noldor and the Sindar (the Elves that migrated to the coast and then stopped) in their struggle with Morgoth.

The Elves build giant cities, create huge armies, and generally do pretty well in the first stages of the war. However, over the 500-plus years that the age lasts, they are slowly ground down by the power of Morgoth and his forces. The Dark Lord has countless orcs, armies of Balrogs, and numerous dragons at his disposal. Men, the Aftercomers, also arrive at this time — with some of them joining the Elves and others joining Morgoth. Dwarves, who had already been around for a while by this time, get heavily involved in the action, too.

Over time, the Dark Lord knocks out one kingdom after another, until the Elves, Men, and Dwarves fighting him are on the verge of extinction. At that point, the half-Elven, half-Man hero named Eärendil the Mariner boldly sales west and begs the Valar to help the rebellious Elves and their allies. His request is granted, leading to the War of Wrath, in which Morgoth is utterly defeated once and for all and the entire western portion of the continent is drowned in catastrophic ruin.

The Elves in the Second Age

The ending of the First Age feels like the end of the story. However, it turns out to be little more than the opening act. When the War of Wrath ends, the Elves who don't return west to the Blessed Realm head east, further into Middle-earth where they set the stage for the Second Age to begin. During this age, they initially thrive, especially under their king Gil-galad. However, about halfway through the age, they run into Morgoth's second in command, Sauron.

Sauron approaches the Elves in disguise, calling himself Annatar, the Lord of Gifts. Some of the Elves buy into this fake persona, especially a group living next to the Dwarven kingdom of Khazad-dûm (i.e. Moria from The Fellowship of the Ring.) Their leader, Celebrimbor, hooks up with Annatar and together they forge a bunch of rings... the Rings of Power. After this, Sauron secretly forges the One Ring and attempts to control the Elves with it. When this fails, Sauron attacks the Elves and almost defeats them. However, they manage to hold on, helped by the powerful race of Men known as the Númenóreans. Finally, at the end of the age, the Elves join with these Men and form the Last Alliance — depicted in the opening sequence of The Fellowship of the Ring — in which they topple Sauron and take his Ring by force.

The Elves in the Third Age

Sauron's first great defeat at the hands of the Last Alliance ushers in the Third Age. This is an age in which the Elves, by and large, pass the baton of world leadership to Men. While they still play an important role in geopolitical events, they are increasingly on the periphery. In their place, the realms of Gondor and its sister nation of Arnor take center stage, holding off the growing might of a resurgent Sauron and maintaining peace in the western lands of Middle-earth.

Nevertheless, we're talking about a 3,000-year-long period of time here, and the Elves aren't sitting around twiddling their thumbs. Throughout these centuries of decline, the Three Elven Rings, eventually worn by Galadriel, Elrond, and Gandalf, are quietly used to help the free peoples of Middle-earth. The Elven stronghold of Rivendell continues to be important, too, as Elrond heals the sick, provides wisdom for those in doubt, and even helps to fight off the threat of the Witch-king.

In the south, Galadriel and Celeborn help to maintain the peace in the Lothlorien. The Elven King Thranduil — Legolas' dad — rules a vibrant Elven kingdom up in Mirkwood, too. Finally, in the northeast of the continent, the Elven lord Círdan keeps the Grey Havens open, where ships steadily set sail for the Blessed Realm, carrying weary Elves to the heavenly safety of that ancient land.

The Elves in the Fourth Age

The War of the Ring (i.e. the events of The Lord of the Rings) close out the Third Age — and they officially put the Elves in a state of retirement. To recap, the Elves had been the primary movers and shakers of the First Age. The Second and Third Ages had been a time in which the Elder Children had slowly taken a back seat to the rising power of the Aftercomers. Now, as the Fourth Age begins with Aragorn ruling a powerful reunited kingdom of Men, the Elves seek retirement over the seas in the west.

A few hints about this final parting process are recorded in Tolkien's writings. For instance, in the prologue to The Fellowship of the Ring, it's stated that after Elrond leaves Middle-earth, "his sons long remained, together with some of the High-elven folk." It also added that Celeborn lives with them for a while after his wife, Galadriel, sets sail for the west.

However, in the appendix to The Return of the King, when Aragorn finally dies, Arwen claims that "There is now no ship that would bear me [to the Blessed Realm]," indicating that the Elven safety valve to the Blessed Realm had officially closed. As far as the Elves that linger in Middle-earth and refuse to leave, Tolkien mentions in his later writing — particularly the book Morgoth's Ring — that their bodies slowly fade and their spirits take over.

The (confusing) Elven afterlife

Tolkien's Elves are immortal. However, immortality is a tricky business, and Tolkien takes quite a bit of time explaining how this deathlessness impacts things like having children and getting married — both of which they engage in slowly and rarely. He also spends quite a bit of time explaining how their immortality impacts Elven lives over the tens of thousands of years of their existence. For instance, in The Silmarillion, he states that "the Elves remain until the end of days... For the Elves die not till the world dies, unless they are slain or waste in grief." He adds that even when their physical bodies die, their spirits are gathered into a very earthbound location ruled by one of the Valar named Mandos. Here, they wait and occasionally are even given new bodies and go back out into the world.

However, while mortal Men are given the gift of death and pass on from the world, it's interesting to note that The Silmarillion also states that Men will eventually join in the post-apocalyptic event known as the Second Music after the Last Battle. The Elves, though? There's no confirmation that they'll be around at that point, with the book stating that "Ilúvatar has not revealed what he purposes for the Elves after the World's end."

Tolkein's Elves and magic

Finally, it's worth touching quickly on the question of Elves and magic. Tolkien's world never outlines a detailed system of magic. Sure, occasionally Gandalf is seen chanting a spell, but for the most part, magic is left mysterious and rarely described. This has led to Tolkien's Elves being vaguely yet regularly connected to the use of magic.

Fëanor crafts jewels that contain self-sustaining light within them. Galadriel utilizes her fancy mirror to see the future. Celebrimbor creates the powerful Three Elven Rings on his own, without Sauron's help. Treebeard tells Merry and Pippin in The Two Towers that "Elves began it, of course, waking trees up and teaching them to speak and learning their tree-talk."

For all of the supernatural behavior, though, Elves are rarely seen as sorcerers or magicians. They don't seem to be interested in conjuring or casting spells. Galadriel even states, in The Fellowship of the Ring, that she doesn't understand what people mean when they say "magic, since "they seem also to use the same word of the deceits of the Enemy." On the contrary, the Elves' magic abilities always seem to stem from their highly spiritual existence, long-developed wisdom and deep knowledge, and close connection with the Middle-earth that they love.