How One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest Is Different From The Book

Ken Kesey's 1962 novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest — and its film adaptation, released 13 years later — left a significant cultural impact. The story, centering on the mistreatment of fictional patients in a psychiatric facility, sparked public interest in mental health practices — helping initiate change in an industry fraught with misinformation, corruption, and a lack of funding.

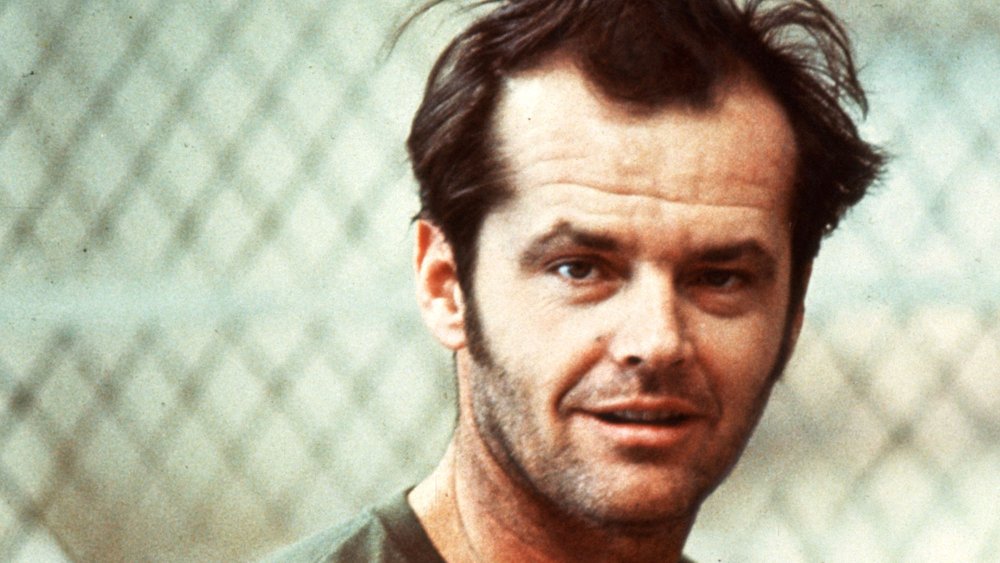

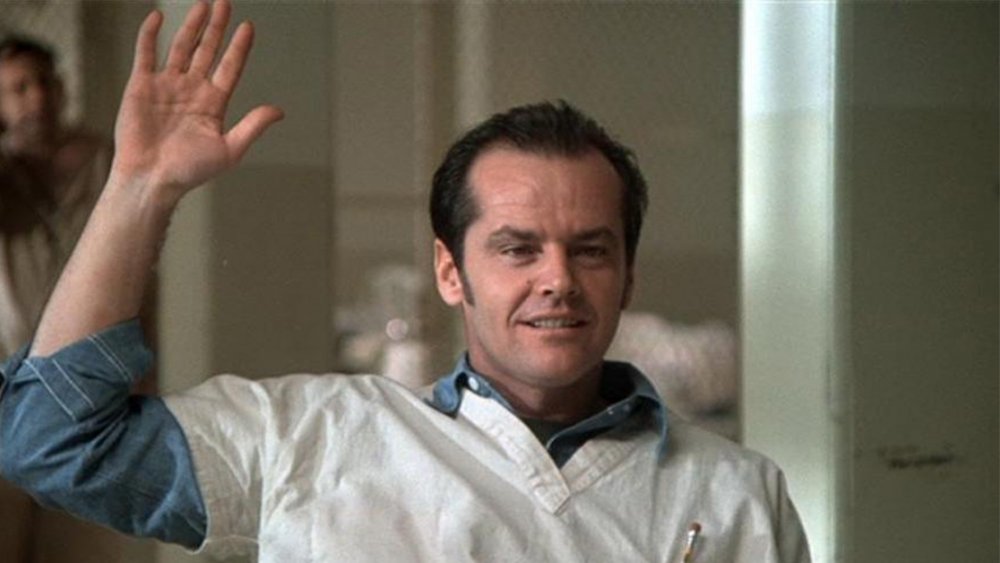

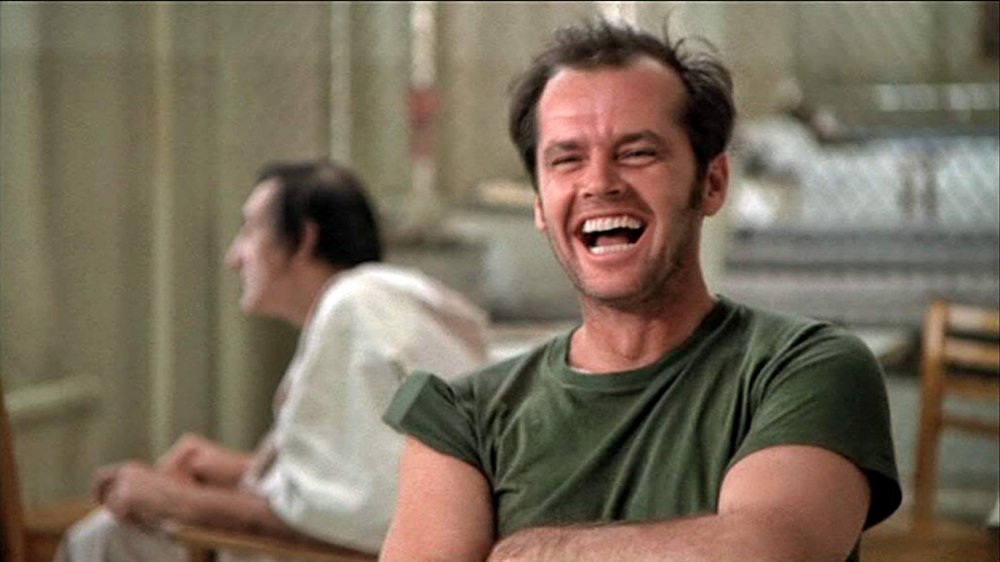

Critics frequently tout the often banned book as one of the greatest American novels. The film swept the 1976 Oscars, walking away with five Academy Awards after nine nominations. The film snagged Best Picture and Best Adapted Screenplay, and Jack Nicholson's performance as Randall Patrick (Mac) McMurphy won him the Oscar for Best Actor. Additionally, Louise Fletcher's chilling performance as Nurse Mildred Ratched won Best Actress, and director Miloš Forman took home the Best Director title.

It's not surprising that the film, which clocks in at just over two hours, removes some of the seminal moments depicted in the novel. Despite the difficulties of adapting a book for the big screen, the film stays pretty true to the source material, but like all book-to-film adaptations, some subtle and not-so-subtle changes were made for the sake of brevity and the nature of displaying scenes as opposed to describing them. Here's a look at how the film adaptation of One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest is different from the book.

Chief narrates the novel

One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest fans who haven't read the book might be surprised to discover that Chief narrates the novel. Right away, readers learn that he's not a "deaf, dumb Indian" — as characters in both versions of the story like to sneer. When Chief (Will Sampson) finally speaks in the film (about Juicy Fruit), the pivotal moment unveils a plot twist, but the film follows ward life in general instead of through his eyes — positioning McMurphy as the protagonist instead of Chief.

The move to make Chief pretend to be deaf while he narrates was a genius play on Kesey's part. For much of the novel, he seeps into the background, neither staff nor patients censoring themselves around him. It's almost like the book has an omniscient narrator, because Chief sees and hears all — because no one thinks he can. It also allows him to provide insider information about the ward, procedures, and patients without needing clunky explanatory dialogue that would otherwise get thrown at McMurphy upon his arrival to the hospital. Instead, those tidbits are dispersed throughout the story as needed. Chief is essentially the most dangerous person on the ward: Not because he's violent, but because he knows things he shouldn't.

Mental health is the book's focus

While both versions of One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest take place in a psych ward, the film doesn't go into much detail about mental health or patient treatment. As a narrated first-person novel, the book allows Chief to specify each patient's diagnosis, the treatments they're getting, and a rundown of meds — and it's apparent that Chief himself is suffering from paranoid schizophrenia. Alternately, the film makes it seem like someone threw him in the ward for prejudices surrounding his half-Indian heritage — which, given the time period, wouldn't be surprising.

Throughout the book, readers glimpse Chief's paranoid delusions about the government bugging his body, and a nefarious network called the "Combine" that he frequently mentions. He's also plagued by "the fog" of his medication and diagnosis. Those details make Chief an unreliable narrator, causing readers to take his version of events with a grain of salt. The film bird's-eye view provides an accurate account of the events without question.

However, Chief lets readers in on his status as an unreliable narrator in Part One. In his own words: "I been silent so long now it's gonna roar out of me like floodwaters and you think the guy telling this is ranting and raving my God; you think this is too horrible to have really happened, this is too awful to be the truth! But, please. It's still hard for me to have a clear mind thinking on it. But it's the truth even if it didn't happen."

One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest's blurry optics

Chief's explanation of patient jargon is sorely missed in the film. Leaving out lingo like "shock shop" for electroshock or descriptors like "Before/After Medication" and differentiating between mobile and immobile patients with labels like "walkers" and "wheelers" takes a lot of character from the story. Yet the movie adds its own level of authenticity: One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest was filmed in a real mental hospital, and patients and staff even joined the cast and crew. This commitment to veracity fits; at age 25, author Ken Kesey had a job as a nurse's aid at a psychiatric hospital, inspiring him to write the novel to call out some of the inhumane practices he witnessed.

The book hones in on the concept of optics, with mental wards trying to look revolutionary and entirely humane. In Chief's descriptions of the goings-on in the ward, he often mentions PR staff giving tours to women's groups, showcasing just how homey the hospital is. Little do those groups know that just one floor up, patients who don't fit into an idealized mold of how someone should behave are forcibly given lobotomies to add to the pile of immobile, peaceful patients. You know, because someone severed their prefrontal cortex.

Ratched is more wretched in the novel

Louise Fletcher's Ratched is certainly no saint, but the nurse frequently referred to as the "Big Nurse" or the "Angel of Mercy" shows her true colors even more prominently in the One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest book. While she rules the ward with a manipulative fist in the movie, the novel takes it miles further, showing moments when Ratched truly loses her chill, yelling at the patients and emphasizing the aggressive half of the term passive-aggressive.

Patients are more aware of her sinister behavior in the book as well. While characters in the film start backing up Mac, the sequence of events plays out more like a "follow the entertaining leader" type of revolution. Most of the ward doesn't admit that the nurse has little to no interest in their actual recovery, or that she's more interested in power and order (a peculiar thing to be hyper-fixated on when running a mental ward). However, the Netflix series that gives the character a backstory, suitably titled Ratched, plays on the idea that circumstances force the nurse to do what she does rather than her insidious control of the hospital wing.

In reality, Kesey wrote the character in a misogynistic manner to trigger fear in readers (and later filmgoers) on the perils of women ditching household chores and taking on authoritative positions. Because women couldn't possibly want to help people for the sake of helping people ... right?

The hospital sanctions the book's boat trip

The One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest movie heightens many of McMurphy's hijinks, but the most significant escalation comes when he escapes the ward, hijacks a bus, and takes the group out on a fishing boat. In the novel, Mac plans the trip for weeks, thwarting Ratched's many attempts to shut it down. While his intentions are mostly to con the patients out of money and hang out with a prostitute named Candy, the event does boost the patients' confidence, giving them a dose of freedom they haven't felt in ages.

When one of the chaperones — also prostitutes — doesn't show, Dr. Spivey even tags along on the trip in the book. They still technically steal the boat from their intended captain, who won't steer the ship without family consent forms from the patients; still, Mac encourages the crew to stick up for themselves when people mock them, and Candy deals with a heavy bout of sexist come-ons from fishermen. Sadly, the patients shrink away from standing up for her despite wanting to.

As is usually the case, the film dramatizes events for entertainment purposes, sometimes even switching characters in scenes to hone in on the protagonist. Film fans see this when Mac refuses to take unknown meds, which happens to Taber in the novel. Other small changes occur throughout the film.

Cheswick drowns in the novel

The only death scenes in the One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest film are saved for the end, when Billy dies by suicide and Chief mercy kills McMurphy after his lobotomy. The book, however, contains multiple deaths. Not only do minor characters around the ward die, but Cheswick drowns in the pool when his hand gets caught in a grate.

The incident occurs after Mac discovers that Ratched can keep him in the ward as long as she pleases since he wasn't a voluntary check-in. Cheswick, who is the first patient to become enamored with McMurphy, loses all hope when his hero decides to toe the line. There's a strong argument that he dies by suicide, as relaying guilt and goodbyes to someone out of the blue are red flags that someone might be planning to harm themselves. Cheswick tells McMurphy that he regrets putting him on the spot and wouldn't have done so if he'd thought it might keep Mac in the ward longer. He mutters that he wished "something might've been done" about Ratched stockpiling his cigarettes right before he dives into the water.

While Cheswick's death clearly results from a lack of sufficient supervision (and the fact that the lifeguard is a patient from the Disturbed ward), Ratched blames McMurphy. Depicting death throughout the film might have undercut the shock that viewers feel when Billy and McMurphy die in the final minutes, so it's arguably to the movie's benefit that Cheswick gets a reprieve in the movie. However, Chief foreshadows those deaths throughout the novel by frequently mentioning that he doesn't understand why patients can't wait to die.

Racism litters the book's pages

The One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest film as well a the novel contain a significant number of moments that have aged poorly when it comes to issues like racism, sexism, and homophobia. However, the book repeatedly hones in on the awful prejudices that existed (and still exist) in society while framing them as acceptable. In the film, Mac makes some incredibly offensive Native American calls when he meets Chief, and the racial divide is evident with the roles the Black cast members fill. The novel, meanwhile, contains a number of offensive racial descriptions and slurs.

At one point in the novel, Chief and Mac throw out a ton of slurs while beating the Black orderlies. Under Ratched's orders, the workers effectively torture George, a patient not seen in the film version, using his obsessive compulsion about cleanliness against him. The scene frames McMurphy and Chief as the heroes for sticking up for George — tacitly accepting the racist treatment the characters dole out.

While the film didn't arrive until a decade later, society had only made incremental improvements in the time since the book's publication in terms of racial equality, and these are barely evident when comparing the movie to the book. One aspect of the novel that didn't get much screen time is Chief's descriptions of his Native American heritage and home — and how the government essentially stole his land and caused his father to lose himself in alcoholism. Chief's lost backstory is one area where the film's altered point of view hurts the story.

Chief plots with the patients in the novel

When Chief raises his hand in the One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest film, Ratched's refusal to honor the baseball vote undercuts the moment. The action seems like Chief is mirroring Mac's movements rather than hearing what he says. In the book, after McMurphy and Chief are sent to shock therapy, Chief drops all pretenses and begins talking to other patients. Many already suspected he was faking, but it's a significant moment of character development for Chief in feeling "big" enough to act instead of trying to blend in.

In both versions, Chief frequently refers to himself as "small." This, of course, references how he's feeling on the inside and not his towering 6'7" stature. In the film, Mac only endures one bout of shock therapy, and seemingly falls in line afterward. In the novel, he challenges Ratched every time she tells him he can stop the procedure by simply admitting his mistake.

The whole ward is terrified for him, devising a plot to help their friend escape, but their plan to set a fire and have Mac escape through the door when the firemen come falls through when Ratched sends McMurphy back to her ward the same day Billy schedules his date with Candy. Instead, they switch the plan to have Mac leave with the girls. Like the movie, though, the drunken rager gets the best of Mac, and it's too late when he wakes up.

Billy Bibbit's fluctuating age

Billy Bibbit is one of the most sympathetic characters in the One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest film and the book, but while he looks very young, the novel reveals that he's actually in his early 30s. The film takes his character in a much younger direction, increasing the emotional stakes. While his death by suicide is a devastating tragedy in both iterations, regardless of age, it hits harder in the movie, thanks to Brad Dourif's moving performance as the adorable boy with a kind heart and a shy stutter.

Both versions of Billy's death are the catalysts that break McMurphy, causing him to violently lash out at Ratched — the nurse who ensured Billy's demise by making him hate himself for sleeping with Candy. Her shaming and threats to tell his mother lead to Billy's impulsive decision — and Mac knows it. He views Billy like a little brother, taking to him more than most patients. McMurphy's lobotomy almost certainly wouldn't have happened if Ratched didn't goad Billy before his death, making the small age adjustment that much more powerful.

Help is available for anyone experiencing thoughts about self-harm or suicide.

McMurphy's revolt succeeds in the book

There are two outcomes McMurphy can spark with his rebellious time in Ratched's ward: His revolt can be the catalyst that gets patients to leave the hospital and veer off on their own, or everything he fights (and dies) for will have been for nothing. The One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest novel takes the former approach while the film takes the latter — and both choices are equally impactful in their own right.

In the book, Mac's efforts to get the patients out of their comfort zone profoundly impact the ward, and the characters begin sticking up for themselves and standing up to Ratched. McMurphy is furious when he finds out that most of the patients signed into the hospital of their own free will — and haven't left for years. It would be one thing if the hospital was actually helping them, but Ratched's rule over the ward through fear and manipulation makes the patients' mental health struggles even worse.

Instead of working with each patient to help them adapt to their diagnoses, Ratched won't even tell them which medications are administered while she plays god with permanent "cures" like lobotomies the minute she deems someone a "problem patient." Between McMurphy's attempts to cheat the patients during gambling schemes, he does teach them to stick up for themselves, encouraging them to have fun — and they win an almost impossible fight. Mac's lobotomy and Chief's mercy killing are enough to prompt many patients to check out and leave the hospital weeks before Chief even escapes.

Mac's impact falters in the film

The One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest film takes a darker turn as patients invent stories that Mac escaped, denying that he was up on the Disturbed ward getting a forced lobotomy. Outside of Chief, Harding is the only patient to see things as they are. But even still, he doesn't sign himself out of the hospital as he does in the novel. The ward goes right back to where it was before Mac came, orderly and neat — and oppressive. No one except Chief escapes or leaves by the time the credits roll, which is a much bleaker outcome than the novel's uplifting one. It's sadly more realistic, however.

Mental health reform is the main issue that drives the novel as well as the film, but the movie gives a more authentic ending that leaves viewers on a bleak note instead of ending with a false sense of security. Additionally, the film likely inspired more people to advocate for change in the mental health system because the plot leaves it open-ended instead of tying it up neatly.

The film's ending highlights how flawed and dangerous the mental health system was (and still has the potential to be). It's often impossible for many patients to escape the impact of poor care after institutionalization. The effects of improper medication, dangerous practices like conversion therapy, or other controversial procedures can last a lifetime. That's not to say it isn't the best option for a many people who commit themselves to humane inpatient facilities. But Ratched's hospital isn't just fiction: for many people, her toxic ward is a reality.