Movie Special Effects You'd Never Guess Aren't CGI

From the mass destruction of Metropolis in "Man of Steel" to the full-length motion-capture madness of "Avatar," computer-generated effects are ubiquitous in Hollywood — so when something amazing happens onscreen, audiences simply assume they're seeing a digital fantasy. But the prevalence of CGI has made audiences a little hard to please: Frequent complaints surrounding modern blockbusters often revolve around shoddy special effects.

There's perhaps a longing for the old days of practical effects, and despite the incredible advancements in CGI over the past few decades, some directors are still committed to doing special effects the old-fashioned way — like they had to in the old days. From puppets to prosthetics to old-school camera tricks, we've rounded up some of the most insane scenes you'll never believe were created without computers.

Flipping a semi truck in The Dark Knight

You might think that Christopher Nolan, a director known for action-packed, ultra-modern, intellectually complex blockbusters, would be all about populating his movies with sleek computer-generated effects. But in fact, Nolan actively dislikes CGI and believes that audiences prefer the real thing as much as he does; hence, he uses practical effects in his films whenever possible. If he can create an explosion using large-scale models instead of digital imagery, he will.

And if he can do it full-size, in real life? Even better. Which brings us to the scene in "The Dark Knight" wherein an epic car chase concludes with a giant 18-wheeler going ass-over-teakettle, right in the middle of a real, actual city block (LaSalle Street in Chicago, which stood in for the fictional Gotham). The effects genies had to use computers to edit out some of the equipment involved in the stunt after the fact, but everything else, from the set to the truck to the end-over-end flipperoo, was completely real. A remote-controlled piston was installed in the semi to propel its rear off the ground, and the scene was filmed from seven different angles — because when you're making an 18-wheeler do a somersault in the middle of the night in downtown Chicago, there is no such thing as a do-over.

The blood-vomiting bed in Nightmare on Elm Street

CGI wasn't much of an option back in 1984, especially for a low-budget horror flick like Wes Craven's "Nightmare on Elm Street." So when Craven's horror franchise introduced audiences to the fedora-wearing movie monster of their dreams, it had to pull off its nightmarish special effects the old-fashioned way—and one moment remains a jaw-dropper even by contemporary standards. It's the scene in which a baby-faced Johnny Depp is dragged through a wormhole in the center of his bed, which then regurgitates his pureed carcass in a spectacular, Old Faithful-esque eruption of gore.

These days, the gravity-defying blood geyser would probably be animated with the help of computers. But for the original "Nightmare," the effects team came up with an inventive (and remarkably budget-friendly) way to pull it off, building the bedroom on a rotating set that could be turned a full 360 degrees. What you see in the blood geyser scene is actually an upside-down image of an upside-down set; once the bedroom was flipped so that the floor became the ceiling, all the producers had to do was pour 500 gallons of fake blood through the bed, and let gravity do the rest.

Werewolf transformations in An American Werewolf in London

Animatronic heads, prosthetic body parts, and the most elaborate assortment of merkins in the history of film: oh my! A lot went into this film's groundbreaking transformation scene, which was achieved with nothing but good old-fashioned practical effects, seamless splicing, and genius foley artistry. Rick Baker, the effects guru who created the monster, made prosthetic versions of actor David Naughton's limbs, then fitted them with air bladders to make them bulge and elongate hideously as Naughton's character turned from man to wolf. For the facial transformation, two animatronic heads (along with Naughton's agonized screams and the overlaid sound of cracking bones) created the illusion of the actor's forehead bulging and jawline reshaping itself into a wolflike snout. And the furry overcoat? That effect was a real-life feat, using latex "skin" threaded with thousands and thousands of wiry hairs. Baker filmed the hair being pulled backward through the skin, then reversed the shot to simulate rapid growth.

The final result was a transformation sequence so realistic and viscerally terrifying that it earned its creator the 1981 Academy Award for Best Makeup. And when the movie got its inevitable 21st-century reboot in the form of "An American Werewolf in Paris," the laughably terrible CGI effects couldn't hold a candle to this practical wizardry.

Dropping a plane in The Dark Knight Rises

Sure, Christopher Nolan prefers practical effects to digital wizardry—but surely he'd let the computers do the work when it came to, say, stripping a plane of its wings and then dropping the fuselage several hundred feet to create the epic plane escape that kicked off "The Dark Knight Rises" ... right?

Nope! Although the actors weren't required to be inside the wingless death tube when it dropped (they filmed their bit inside a set piece planted firmly on the ground), Nolan really did dangle half a turboprop plane vertically from a helicopter—and then cut it loose to crash (in a pre-approved, unpopulated rural area).

Anti-gravity fisticuffs in Inception

Nope, we're still not done with Christopher Nolan. The Dark Knight director didn't limit his commitment to practical effects only to his Batman franchise; it's something he swears by in all his films, including the 2010 blockbuster "Inception." To create this gravity-defying dream-within-a-dream fight scene, the moviemakers built the 100-foot-long hotel hallway on a rotating set—a funhouse landscape the actors spent weeks learning to navigate. According to Joseph Gordon-Levitt, the process required as much mental flexibility as it did acrobatic balance.

"I couldn't think of the floor being the floor and the ceiling being the ceiling," he told E! Online. "I had to think of it like, 'This is the ground. OK, now this is the ground. And now this is the ground.' It was just that the 'ground' was always moving under me. That was the mind game I had to play to make it work."

With a camera mounted on a track that ran the length of the set, Nolan was able to create seamless, stable shots even as the hallway itself spun 360 degrees.

The Jurassic Park T-Rex was the real deal

Hold on to your butts! There's a reason the lizard king of Stephen Spielberg's 1993 sci-fi thriller was such an imposing presence onscreen: he was a real-life, full-sized animatronic, no CGI trickery required. The T-Rex weighed 9,000 pounds and was built on a skeleton made of hydraulic motors and moving metal parts, like a giant erector set. And despite being man-made, he was decidedly dangerous: during the production, a crew member nearly lost his life (or at least some essential body parts) when he was unlucky enough to be stuck inside the belly of the beast during a power outage.

Meanwhile, even the digitally enhanced dinosaurs of "Jurassic Park" were often a combination of CGI and puppetry. For instance, the brachiosaurus that sneezed all over Lex was only a digi-saur from the neck down. The big cow-like head that the kids interacted with was really there ... as was the copious spray of dino snot. (Poor Ariana Richards was repeatedly blasted with a cannon full of viscous goo to create that iconic gross-out moment.)

Little Hobbits, big world

Rather than shrinking Elijah Wood (or embiggening Ian McKellen) in post-production, Peter Jackson used an old-school optical illusion to make his Hobbits teeny-tiny in comparison to all the wizards, orcs, elves, and other full-sized folks who roam around Middle-earth. The trick is forced perspective, in which camera angles, cropping, and the actors' relative positioning combine to make them appear differently sized. In theory, it's simple physics; in practice, it meant that every shot had to be staged down to the millimeter. Jackson used forced perspective throughout the "Lord of the Rings" trilogy, and stuck to the same method when he tackled "The Hobbit" a decade later — because unlike those cringeworthy green CGI ghosts in "The Return of the King," this kind of classic effect never goes out of style.

The liquid metal villain of Terminator 2: Judgment Day

In 1991, "Terminator 2: Judgment Day" was a groundbreaking example of the power of digital effects, boasting CGI that went miles beyond anything else on the Hollywood landscape. But what made the movie so spectacular wasn't the CGI alone, but the way James Cameron seamlessly integrated the computer-animated cuts with practical effects. For every purely digital shot of T-1000 slithering around in liquid metal form, there was a scene rendered the old-fashioned way, with puppets and makeup and expert camerawork that gave the film a sense of real-world weight.

Most incredibly, every time T-1000 was blasted apart — with a shotgun early in the film, or with a bazooka in the villain's climactic death scene — Stan Winston's special effects team would bring in a mangled, metallic-accented puppet (featuring a clay cast of Robert Patrick's head) to thrash around. In T-1000's last moments, the blown-up puppet is so seamlessly intercut with computerized motion-capture effects that you can't even tell where one ends and the other begins.

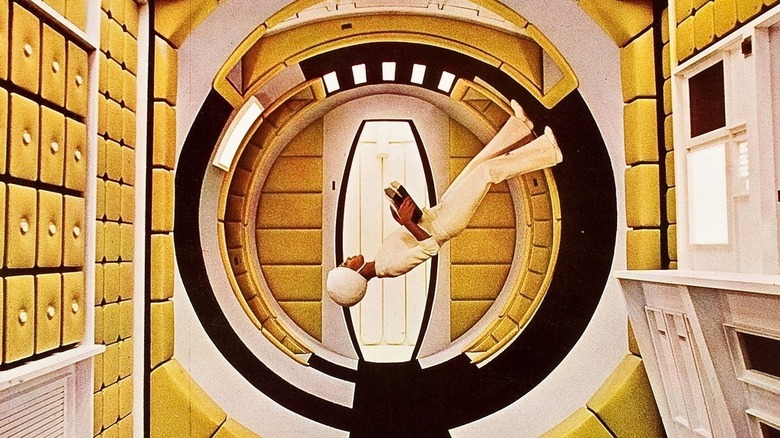

The zero-gravity jog in 2001: A Space Odyssey

Stanley Kubrick's legacy sci-fi film might have taken place in 2001, but it was filmed in 1968 — which means that not one single scene in this movie was achieved with the help of digital imagery. That's impressive on a lot of fronts, but the most amazing, inventive practical effect has to be the one Kubrick used to create the iconic scene in which an astronaut turns the vertical circumference of his spaceship into a jogging track, running up the wall, across the ceiling, and back down to do it all over again.

In practice, the actor playing the astronaut actually ran in place the entire time — while a set which was essentially a giant hamster wheel passed beneath their feet, and a camera swooped up and around and down to create the impression of a body in motion.

Blowing up the White House in Independence Day

Nowadays, it's de rigueur for Hollywood's biggest-budget blockbuster movies (like, say, the "Independence Day" sequel) to feature hyper-realistic computer-generated explosions that are virtually indistinguishable from the real thing. But back in 1996, animating a giant fireball using CGI was still touch-and-go — which is why Roland Emmerich and his special effects team went ahead and blew up the White House the old-fashioned way.

That is, building a 1:24 scale model with all the gorgeous detail of the original, and making it go kaboom. (What is this, a White House for ants?)

The five-foot-tall model White House looked convincingly real even in close-up; it's no surprise that the scene of it being blasted to bits is still one of the most iconic explosions in the history of cinema. When it came time for the effects team to blow up their plaster model, the actual big bang moment went off without a hitch — and CGI was more than up to the task of adding in an alien laser beam after the fact.

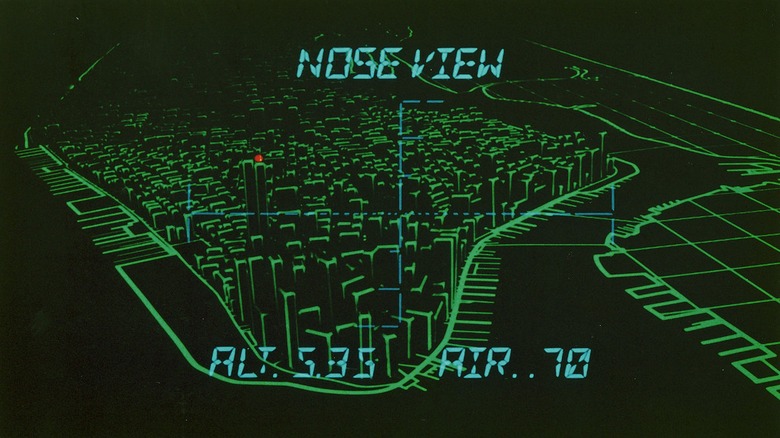

Snake Plisken's digital wireframe cityscape in Escape From New York

In "Escape From New York," Snake Plissken is tasked with entering the island of Manhattan by landing a glider on one of the Twin Towers. As he glides to his destination, the computer monitor displays a 3D topographical view of the cityscape with some information about his altitude and speed. The wireframe city features all the skyscrapers and smaller buildings just as they looked at the time of the film's release in 1981.

The detail of the buildings increases as he gets closer, showing the structures' various windows and weighted lines. This type of wireframe rendering was fairly common in the early days of CGI, but there's no computer wizardry at work, as rendering the whole city would have been too expensive. To make the city appear like a wireframe display, VFX artists John Wash and Mark Stetson created a 3D model of the city they shot to make it look realistic.

Wash had Stetson meticulously construct the buildings out of painted black and white plastic and routed-out lines, revealing the opposing color. Stetson created a miniature model of the city and larger models of individual buildings for close-up shots. Their work tricked most people into believing it was a standard CGI wireframe, including one who critiqued his work by calling him out for using CGI to render the sequence.

All the jets and flying scenes in Top Gun: Maverick

"Top Gun: Maverick" features a ton of aircraft flying in over-the-top situations. Tom Cruise may have a pilot's license, and he's more than qualified to fly some aircraft, but that doesn't mean the U.S. Navy handed him the keys to an F/A-18E/F Super Hornet and let him go wild. Despite this, there is very little CGI in the film, as nearly all shots were done practically from the cockpit of real jets, so the actors experienced it all.

The actors didn't fly the jets but sat in the cockpits behind the pilots. When they move the stick in the movie, they're mirroring what the pilots are doing, making for an incredibly realistic depiction of aerial maneuvering. The actors trained and received all the instructions they needed from the director, so when they sat in the cockpit, they acted out their scenes in front of several cameras. If something went wrong, they had to do it all over again.

One of the most spectacular practical shots in the film is at the very beginning. Director Joe Kosinski told IGN that when Maverick flies the Darkstar over Chester Cain (Ed Harris), "It destroyed the set. You watch it rip the roof off the guard shack. That was not planned. That was a one-take thing where we destroyed the set, and that's the only shot we got, and that's in the movie."

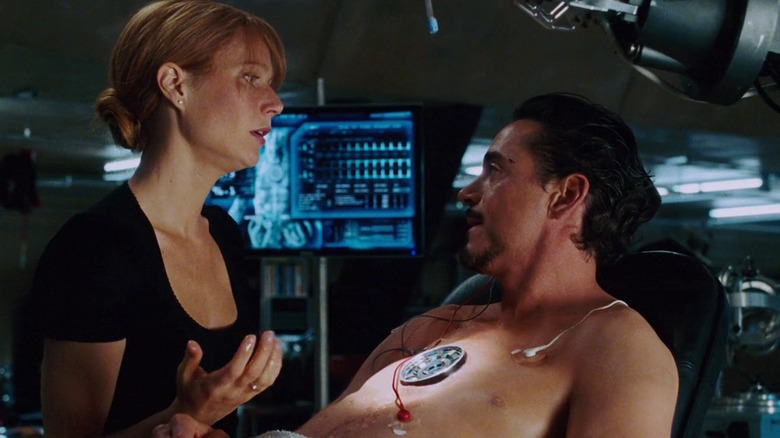

Pepper changing out Tony's Arc Reactor in Iron Man

In "Iron Man," Tony Stark (Robert Downey Jr.) upgrades the miniature Arc Reactor implanted in his chest and requires Pepper Pott's (Gwyneth Paltrow) help to swap it out. As calmly as possible, Tony talks her through the procedure while lying back in a chair. She removes a wire and an attached magnet, which touches the sides, making for a realistic live-action recreation of the board game Operation. The scene is so realistic that it had to be CGI — after all, she reaches into the man's chest.

Unlike most of the CGI special effects used in the movie, the filmmakers used a tried and true method: prosthetics and camera trickery. The VFX artists created a prosthetic chest fitted with a hole for the reactor. Downey situated himself under the char with his head and arms poking through. The prosthetic was attached by makeup artists, making it appear like Pepper truly digs into Tony's chest.

The practical special effect of the chest included air bladders, which simulated Tony's breathing. This gave the prosthetic a realistic look, and with the makeup artists' work blending it into Downey's upper body, you can't tell it isn't real in the movie. Granted, if you look close enough, you can see that Downey's breathing doesn't perfectly align with the chest's movements, but you have to look very closely to see the difference.

The nutty squirrels in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory

While the 1971 version of "Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory" didn't feature a squirrel scene, instead opting for geese, the 2005 Tim Burton adaptation of Roald Dahl's novel does. The scene plays out much as it does in the book, with Wonka (Johnny Depp) showing off his nut-sorting room to the group. The squirrels sit neatly on stools and tap each nut before removing the shell while discarding any that don't meet Wonka's strict standards.

Veruca Salt (Julia Winter) tells her father she wants a trained squirrel, and things devolve into funhouse child endangerment, as you'd expect. Burton had the option of using CGI to render the squirrels, which move and act in very non-squirrel-like behavior. Instead, the director settled on 40 highly trained squirrels, though he initially wanted 100. The squirrels required three months of training to get them to do the needed actions for each shot.

They began by running through a tube, then to a stool, and then learned to sit still and remove nuts from their shells. The nuts in the movie aren't real, which kept the squirrels from trying to eat them, though it took an average of 2,000 repetitions for each squirrel to do it properly. Animatronic and CGI squirrels were added to the background of the scene, while the close-ups all feature real squirrels cobbled together into composite shots to achieve the desired result.

The weightless scenes in Apollo 13

In "Apollo 13," three astronauts travel to the Moon, but their mission turns into a desperate race for survival when an accident cripples their spacecraft. The film depicts the true story of the Apollo 13 mission from April 11 to April 17, 1970. Jim Lovell (Tom Hanks), Jack Swigert (Kevin Bacon), and Fred Haise (Bill Paxton) use every tool at their disposal while receiving frenzied guidance from NASA headquarters in Houston, Texas, to return to Earth safely.

Since all the action occurs between the Earth and the Moon, the astronauts experienced weightlessness for most of their journey. Movies have depicted weightlessness in various ways over the years, and there are practical means of accomplishing this on the ground. Using wires and camera tricks often gets the job done, but director Ron Howard wanted his long shots to be realistic, so he did it for real with something NASA likes to call the Vomit Comet.

The Vomit Comet is a KC-135 aircraft that flies up and down in a parabola, so that when it reaches the height of its ascent and begins to descend, everyone on board experiences 25 seconds of weightlessness. The filmmakers acquired the aircraft for six months and built the sets inside. The actors filmed their scenes during these short periods of weightlessness while the director and crew sat nearby, shooting around 40 parabolas in the morning and 40 in the afternoon.

Luke destroys the hut on Ach-To in Star Wars: Episode VIII - The Last Jedi

Ever since George Lucas played around with the original trilogy by releasing the Special Edition, "Star Wars" has been rife with CGI. That's remained true well into the 21st century, so you're not seeing many miniatures or painted matte backgrounds in the franchise past the 1990s. "The Last Jedi" is no stranger to CGI, but there's one scene, in particular, that looks like it uses CGI when it is in fact an entirely practical effect.

In the film, Rey (Daisy Ridley) discovers that she has a link with Kylo Ren (Adam Driver), and they communicate over vast distances using the Force. This connects them physically to an extent, and while Rey is on Ach-To, she and Kylo Ren touch hands right as Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill) steps inside the hut. He sees his former Padawan touching hands with Rey, extends his hand, and shouts, "Stop!" As he does this, the individual stones of the hut's upper half break away in all directions.

It's a captivating scene that displays Luke's power, and there's no CGI involved. The stones were made of foam and were simultaneously pulled away from the center of the hut with strings. It's one of the oldest tricks in filmmaking, and it works perfectly in the scene. Director Rian Johnson used practical effects whenever possible, following Lucasfilm president Kathleen Kennedy's guidance from before the production of "The Force Awakens."

Peter Parker catches everything in the cafeteria in Spider-Man

Sam Raimi's "Spider-Man" brought everyone's favorite wall-crawler to live-action, and it was an incredible success. The film tells the origin of one of Marvel Comics' most popular characters, tracking Peter Parker (Tobey Maguire) as he navigates his adolescence while learning to use his newfound superpowers. The film has plenty of CGI, which blends seamlessly with various practical effects to make for a grand cinematic experience.

One scene early in the film has Peter catching Mary Jane (Kirsten Dunst) after she slips in the cafeteria. Her food goes flying and Pete catches it all on a tray, impressing M.J. and the audience at the same time. Catching all of that food might seem impossible, but Maguire did it for real. It took quite a few takes before he managed the feat, so his and Dunst's surprised reaction in the scene is genuine.

On the film's DVD commentary, SFX artist John Dykstra explained, "This gag when he catches all this stuff, he actually did that ... take 156" (via Metro.co.uk). Later in the commentary, Dunst confirmed that it was all Maguire, explaining, "Not CGI, by the way, that's all Tobey, which is pretty impressive. They used sticky glue stuff to stick his hand to the tray" (via Independent). All 156 takes required a full day of 16 hours before Maguire nailed arguably one of the film's most memorable scenes.

All the web-slinging in The Amazing Spider-Man and its sequel

One of Spider-Man's signature moves is slinging some webbing and swinging through the streets of New York City. He's been doing it for decades in the comics and keeps it up in "The Amazing Spider-Man." While Sam Raimi opted for CGI in his "Spider-Man" trilogy, director Mark Webb opted to accomplish the web swinging practically in both "Amazing Spider-Man" films. Some elements did include CGI, but most of the swinging in the movie is real.

Stunt coordinator Andy Armstrong told Entertainment Weekly how he succeeded in stepping away from the computer to literally swing stunt workers through the sets at breakneck speed. "I brought in an Olympic-level gymnast. ... videoed it from every angle and then analyzed the video." Noting the variation in speed from the downward motion to the upward swing, Armstrong developed machinery to mimic the movements safely.

His equipment accelerated the stunt worker or actor, pulling many Gs as they swung all over the place. They used a winch to pull and then stop the motion, similar to cracking a whip, so the person at the end of the line was able to sync up their movements. Ultimately, Armstrong generated realistic movements by safely whipping someone about through a combination of athleticism and mechanical engineering, ensuring that Spider-Man's web-swinging in "The Amazing Spider-Man" is as natural-looking as possible.

Rey's magical bread and BB-8 in Star Wars: Episode VII - The Force Awakens

"The Force Awakens" introduces Rey to the "Star Wars" franchise, as she ekes out a living scavenging parts from destroyed starships. In her introductory scenes, she takes a bunch of salvage to Unkar Plutt, who gives her a quarter portion of rations. She takes what he offers and settles in for a nice meal. After sprinkling some powder into some water, which she stirs with her finger, the water disappears as a small loaf of green bread rises.

Rey picks up the bread and eats it, and it's all done in one swift motion without any camera movement, making it seem unreal. Special effects supervisor Chris Corbould told MTV News how they made the bread, which doesn't use CGI. "Surprisingly, that was done practically, although so many people have said to me, 'We thought that was a digital effect!" Corbould explained that it took three months to develop the shot.

A lot of time and effort went into designing the product so that it looked like bread, although it apparently tasted terrible and had no nutritional value. Another practical effect in the film is BB-8. It's difficult to believe, given the spherical nature of the character, but the BB-8 you see in the movie is a real robot created for the film. Tons of engineering went into making him work, with the head being the most complex part of his design.

The destructive highway chase scene in The Matrix Reloaded

"The Matrix" franchise is full of CGI — which makes sense, seeing as it's about a computer-generated environment made for humans by machines. In "The Matrix Reloaded," an extensive freeway scene features Morpheus (Laurence Fishburne), Trinity (Carrie-Anne Moss), and the Keymaker (Randall Duk Kim) making their way to an exit point as Agents chase them. The Agents routinely crash and destroy all kinds of cars as they make their way to the heroes, and some of this is done using CGI.

When the people transform into Agents, and when those Agents jump from one car to another, destroying them, you can rest assured there's CGI in those shots. That said, most of the scene doesn't involve any CGI at all. The filmmakers built the 1.25-mile freeway specifically for the scene. It features three lanes on each side with 19-foot-high walls along its length. It cost $2.5 million, and the filmmakers built it on Alameda Island, California.

Some of the vehicles in the freeway scene are CGI, but not many aside from a few seen in the background. The filmmakers did this so stunt drivers could safely maneuver at high speed along the road. Outside of that, what you see is a combination of excellent editing, innovative camera work, talented stunt drivers, and a ton of destroyed cars. Many viewers likely took the freeway scene for granted, but a great deal of technical prowess went into bringing it to life.

The Trinity test explosion in Oppenheimer

Christopher Nolan's "Oppenheimer" tells the story of the eponymous physicist and his work on the Manhattan Project. The film builds up to the climactic detonation of the first atomic bomb during the Trinity Test, which took place near Los Alamos, New Mexico. The film features a brilliant explosion coupled with masterful sound editing that puts the viewer in the bunker with the scientists experiencing the detonation, and it's epic.

Nolan obviously couldn't use a real atomic bomb for the film, but that didn't stop him from skipping the CGI. Using computer-generated effects for the explosion would have been relatively easy, but Nolan wanted to do it practically — minus the plutonium and nuclear fission. Nolan told The Hollywood Reporter, "This can't be safe. It can't be comfortable to look at it. It has to have bite. It's got to be beautiful and threatening in equal measure."

Nolan tapped visual effects supervisor Andrew Jackson to create the explosion using only practical means, and he did a fantastic job. Jackson and his team set up nearly ten explosions using high explosives and barrels of fuel. The barrels launched into the sky, creating the mushroom cloud effect, which they shot with numerous cameras using multiple framerates and various lenses. Jackson told The Sydney Morning Herald, "They were really just big explosions that we treated in a way to make them feel much bigger than they really were."