The History Of Looney Tunes Explained

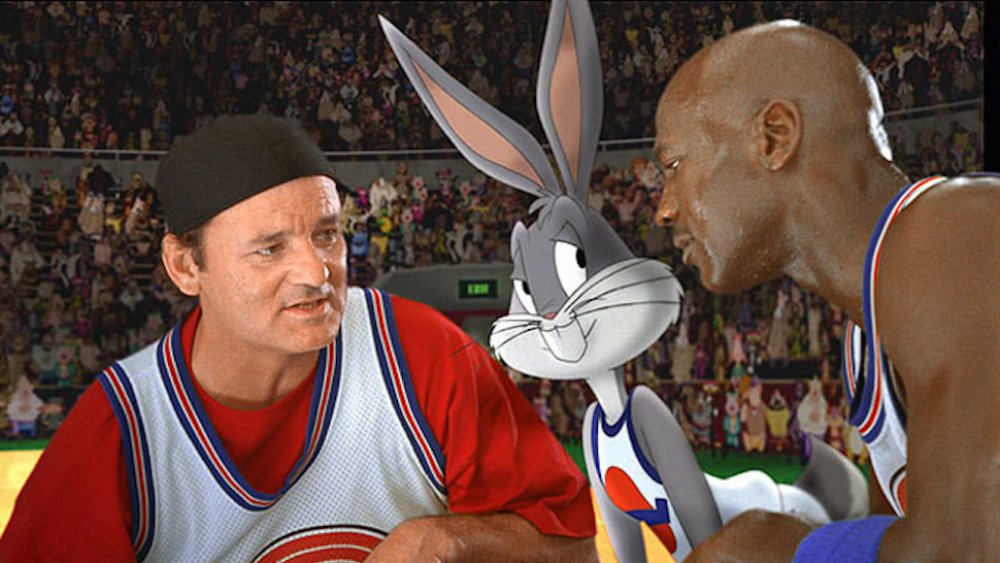

For close to 100 years, Looney Tunes has been so much a part of American pop culture that it's hard to imagine a world without it. Without Looney Tunes, we couldn't say a toddler sounds like Elmer Fudd or a bad French accent sounds like Pepe Le Pew. We couldn't zip around like Speedy Gonzales, and annoying little critters wouldn't be "varmints." We almost certainly wouldn't ask "What's up, doc?" or "Ain't I a stinker?" Dynamite would only be for mining. Anvils would only be for shoeing horses. And while a generation of kids might have still grown up worshipping Michael "Air" Jordan, we would have lost the chance to see him spar with Bugs Bunny as Hare Jordan in Space Jam.

That's a lot of history, and as we celebrate these cartoon stars' longevity with the new series on HBO Max or look forward to their return to the big screen in Space Jam: A New Legacy with LeBron James, it's worth taking a moment to look back at how we got here. These classics didn't just come out of thin air, after all. They were the work of a collection of personalities every bit as colorful as their animated menagerie of ducks and wabbits. Let's take a look!

In the beginnning

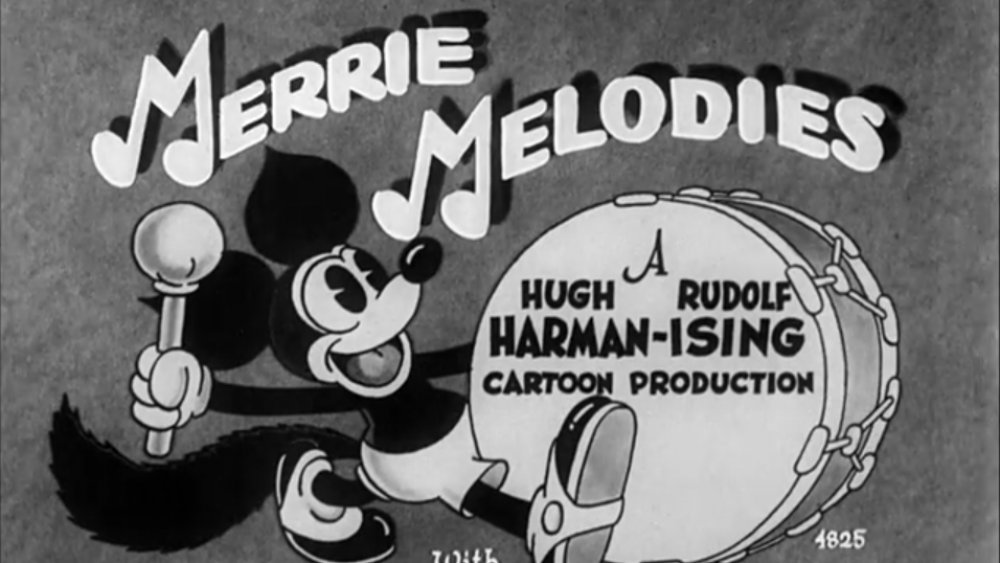

For such a forgotten series, the silent adventures of a character named Oswald the Lucky Rabbit had a huge influence on animation history. In 1928, when producer Charles Mintz tried to strong-arm Walt Disney into a less lucrative contract, Disney left Mintz to start his own studio, which you may have heard of. Mintz himself lost the series, leaving his star directors Hugh Harman and Rudy Ising to follow Disney's lead. They took some of their fellow out-of-work animators and moved to Warner Brothers.

Disney's Silly Symphonies series was already hugely popular when Harman and Ising picked up stakes, so they apparently consulted a thesaurus to create their own Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies. For most of their first decade, the shorts lived up to their name: They were the Old Hollywood equivalent of music videos, less focused on plot or comedy than selling Warners' library of sheet music.

As critic/historian Leonard Maltin observed, the early Looney Tunes also lived up to their name as far as originality went. Like most contemporary cartoons, the first Tunes were blatant ripoffs of Disney's Silly Symphonies formula, starring a parade of Mickey Mouse lookalikes with names like Bosko, Foxy, and Piggy. But changes were coming that would turn Looney Tunes into something completely different from Disney, or anything anywhere in the animation industry up to that point.

New staff, new stars

In 1934, Harman and Ising moved again, this time to MGM. That left producer Leon Schlessinger in charge, and he set to work assembling a new crew of filmmakers to continue the series. Their studio was a cardboard shack so ramshackle they nicknamed it "Termite Terrace." That should give you a good sign of how little Warner Brothers cared about their cartoons. That meant they didn't have many resources — as great as they are, the classic Looney Tunes never could afford the gorgeously detailed animation of Disney or MGM. But that also meant they didn't have much oversight, and that let the Termite Terrace crew take animation to exciting new places. They started looking less to the orderly cuteness of Disney and more to the chaotic slapstick of live-action stars like the Marx Brothers and Laurel and Hardy.

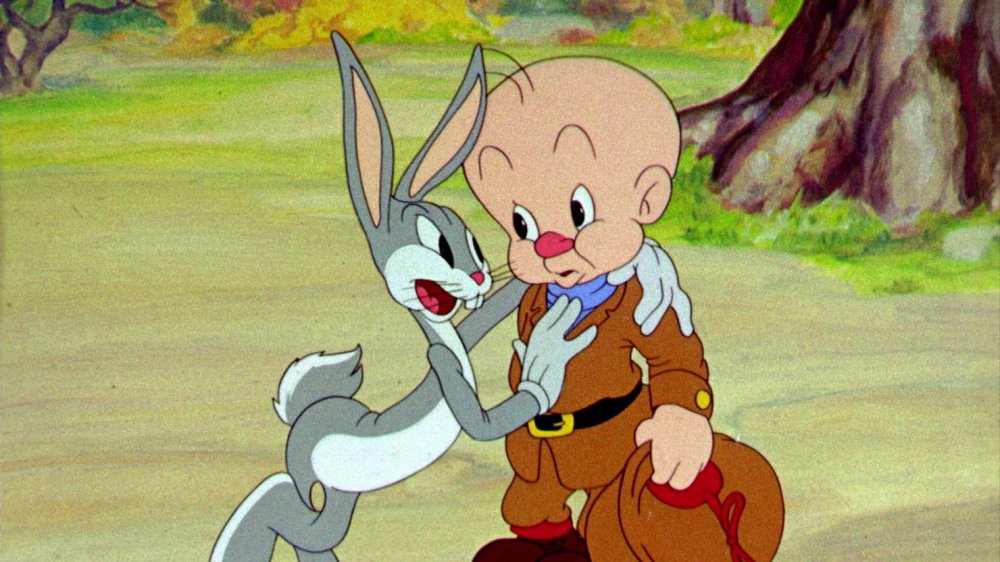

This meant they needed new characters who had strong enough personalities to instigate this kind of anarchy. One presented itself in I Haven't Got a Hat the year after Harman and Ising left. That was Porky Pig, a fat little schoolboy who soon evolved into the ultimate straight man, able to withstand the wackiness of his new castmates. He met Daffy Duck in Porky's Duck Hunt in 1937, the same year Disney entered feature filmmaking with Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. After that, the floodgates were open, and as a new decade dawned, A Wild Hare introduced Termite Terrace's greatest creation of all: a wascally wabbit named Bugs Bunny.

Tex Avery - Making Looney Tunes looney

Even though his stay with the studio was brief, Tex Avery may have done more than anyone else to turn Looney Tunes into what they are today. He arrived at the Warners lot and said, as he recalled later, "Hey, I'm a director.'... I was no more a director than nothing, but with my loud mouth, I talked him into it." Since the studio was overcrowded, the higher-ups moved him into the bungalow that became Termite Terrace.

His first cartoon, Gold Diggers of '49, set the tone, running almost literally twice the speed of the earlier Harman-Ising joints. He directed both Bugs and Daffy's first appearances, and in A Wild Hare, he created another character named Egghead who he molded into the Elmer Fudd we know and love today. He also introduced the cartoon physics that allowed characters to defy gravity in midair and pop their eyes out of their heads, and the tradition of caricaturing contemporary stars that allowed many of them to live on long after their actual movies had been forgotten. He even proved he could go toe to toe with Disney for gorgeous spectacle in his art deco short Page Miss Glory.

Avery left for MGM soon after debuting Bugs, and with the budget to realize his wildest ideas, he did his best work there. MGM was also where he created yet another cartoon icon, Droopy Dog, whose implacable sad-sack-ness made him the perfect foil to all the wacky slings and arrows Avery threw at him.

Mel Blanc, the man of a thousand voices

Around the time Tex Avery arrived on the Warners lot, the studio took on another new hire who literally gave Looney Tunes its voice. His name was Mel Blanc, and he started out playing a few background characters. Then he was called in to replace Joe Dougherty as Porky's voice, since Dougherty really did have a stutter, taking hours to record.

From then on, Blanc played almost every single one of Looney Tunes' cast of thousands, with a few exceptions, like Elmer Fudd (Arthur Q. Bryant) the Roadrunner (sound effects artist Treg Brown), and most of the women's parts, played by Bea Benaderet and June Foray, who both played Tweety's Granny. Blanc even played iconic cartoon characters for other studios: He was Barney Rubble on The Flintstones and originated the role of Woody Woodpecker, basing his trademark laugh laugh on childhood memories of using it to test the echoes in the empty hallways of his school.

Blanc's work was literally his life. A car crash once left him comatose, and after days of failing to get a response out of him, a nurse thought to address him as "Bugs." He responded, "Eh... just fine, Doc. How are you?" and the nurse ran through his other characters until he finally woke up.

Carl Stalling, musical collage artist

Mel Blanc was only responsible for half of Looney Tunes' sound. The music that ran under his many voices was the work of Carl Stalling. Stalling came to Looney Tunes after many years defining the sound of Disney's cartoons from the very first Silly Symphony, The Skeleton Dance. Looney Tunes was the best gig he could have asked for. He got to conduct Warner Brothers' entire 50-piece orchestra, a privilege no other animation studio offered.

And Warner's massive library of pop hits gave him an opportunity to mix and match in ways that would have seen him recognized as an avant-garde genius if he hadn't been scoring wascally wabbits and bad ole puddy tats. Stalling's scores could switch within seconds from centuries-old classical symphonies to the latest pop hits to jazz improvisations. He introduced millions of kids to classical music and saved songs like "Ain't She Sweet" and "We're in the Money" from obscurity.

His scores could set the mood or drop in little inside jokes for viewers who recognized his sources. He created cartoon shorthand that animators still use today, like playing a slide whistle for a long fall, or running up the scale in time with characters running up stairs.

Bob Clampett, Looney Tunes' looniest director

When Tex Avery moved into Termite Terrace, he requested two animators who would go on to direct their own shorts: Bob Clampett and Chuck Jones. Though they had the same mentor, they couldn't have been more different. Jones was all about subtle turns of phrase and letting gags slowly build. His funniest animation often involved no animation at all — just a long look at a character's frozen face. But Bob Clampett's cartoons are manic even by Looney Tunes standards. Animators like to describe their most natural work as "fluid," but Clampett's is downright liquid. His characters melt, warp, squash, and stretch. They'll be standing around in the background and suddenly stick their faces right in the camera.

But he was also capable of a more realistic approach, like in these tests for a John Carter of Mars movie he was developing with Tarzan creator Edgar Rice Burroughs. Not only would this movie have beaten Disney's version to theaters by over 75 years — if it had been completed, it would have given them some competition in the feature animation market that they monopolized for decades.

Clampett doesn't have quite the body of work some of his peers do, since he left Warners in 1945. But he left quite a legacy behind. He created Tweety Bird, and his manic style has been the go-to influence for countless cartoons since, from Who Framed Roger Rabbit? to Animaniacs to the new Looney Tunes Cartoons on HBO Max.

Chuck Jones, creator of classics

Chuck Jones, on the other hand, was more of a late bloomer. His early cartoons tried to bring Warner back to its roots as a Disney imitator, but the results were too dull and cutesy to make much impact. But when he found his voice, he proved it was the most exciting and unique one Looney Tunes had. Adapting the witty wordplay of writer Michael Maltese, he began developing his cartoon characters into three-dimensional personalities. When they debuted, Bugs and Daffy were both one-note pranksters. Jones dialed up Daffy's human failings and Bugs' superhuman cool until they were polar opposites.

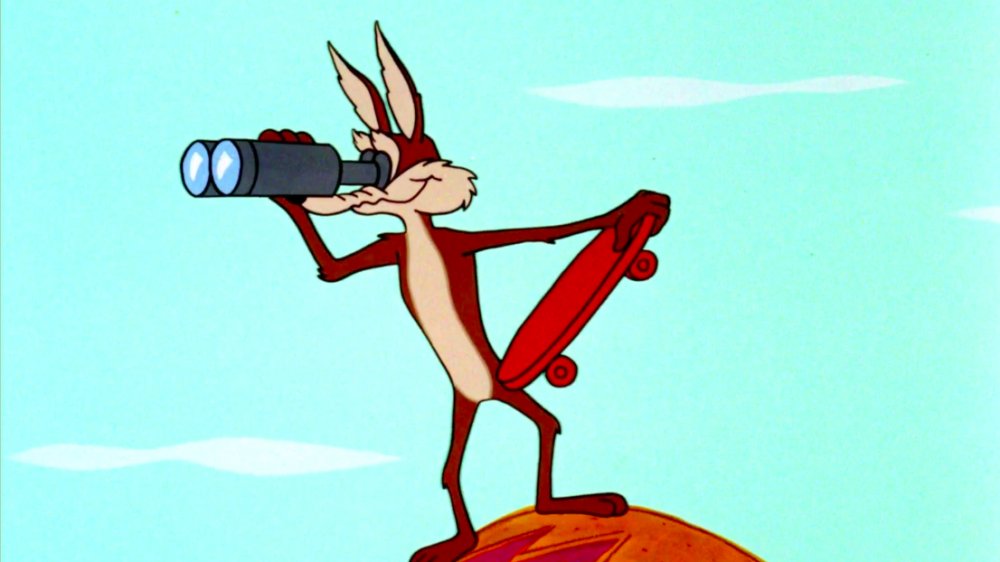

And he created plenty of memorable characters of his own, like Pepe Le Pew, Marvin the Martian, and most notably, Wile E. Coyote and the Roadrunner. Jones made dozens of cartoons with these two, never varying the bare-bones chase plot, and still squeezing hilarity out of it every time. Other cartoons ignored recurring characters altogether to create strange little short stories that could be incredibly moving, like Feed the Kitty, or inspire more complicated, uncomfortable emotions, like One Froggy Evening.

Looney Tunes absorbed the broader art world's trends towards abstraction in the '50s, and Chuck Jones' cartoons became even more striking as he worked with art director Maurice Noble to create gorgeous landscapes in classics like What's Opera, Doc? or Duck Dodgers in the 24 1/2th Century! Most famously, in Duck Amuck, he deconstructed the whole animation medium, pitting Daffy in an existential struggle with his all-powerful animator.

Friz Freleng, the master craftsman

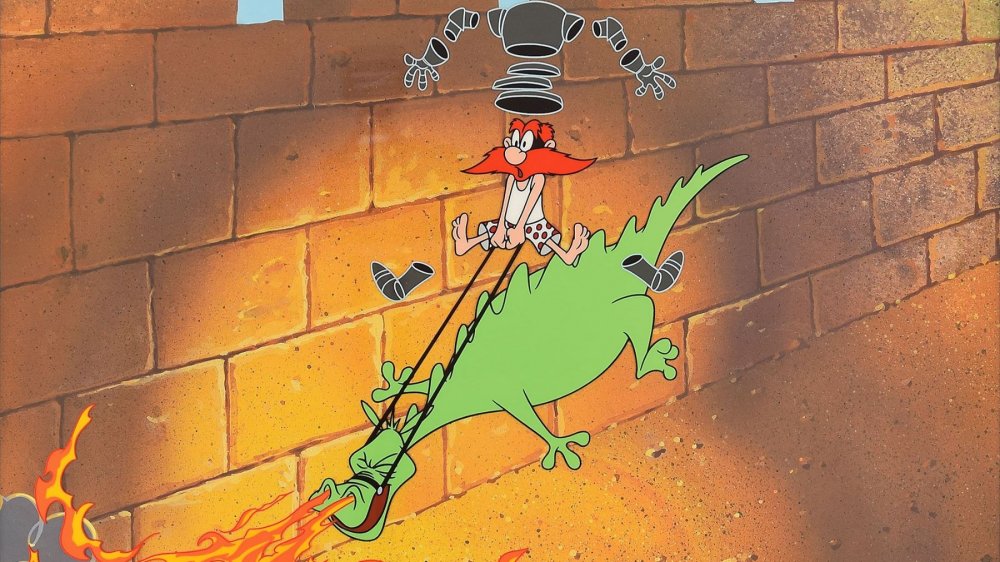

If Chuck Jones is what film buffs like to call an auteur — an artistic voice who imprints his unique style on everything he does — then Friz Freleng is the ultimate journeyman. Journeyman directors are often ignored because their work isn't as easily identifiable, but it's still recognizable from its consistent quality and painstaking perfection. Freleng took his business seriously, timing every cartoon down to the nanosecond for maximum laughs. Jones has said he even used sheet music instead of storyboards to get it just right, and each of his cartoons really does flow like a symphony. And he's one of most consistent presences in Looney Tunes' history — he was one of the Oswald animators Harman and Ising took with them when they first founded the studio!

He was also a character in his own right — literally. With his red hair and hair-trigger temper, he inspired Mel Blanc and the animators in creating Yosemite Sam. He apparently took the ribbing well, since he directed dozens of cartoons with the little cowboy throughout his career. Freleng even said Sam was one of his favorites, since he always felt pitting Bugs against little Elmer Fudd made him look like a bully and Sam gave the wabbit a real threat to match wits with. Freleng was also responsible for pitting Clampett's Tweety Bird against his own creation, Sylvester, and he'd later create Speedy Gonzales as another sparring partner for the bad ole putty tat.

Bob McKimson - More is more

When Bob Clampett left in 1945, he turned over his unit to one of his star animators, Bob McKimson. McKimson, part of an animation dynasty with his brothers Charles and Tom, kept his mentor's style alive, literally warping the characters around his imprint — they all have much bigger mouths and jowls in McKimson cartoons than anybody else's.

Fans tend to call him the least of the classic directors, but the least of such a talented bunch has more creativity than the best of most studios. If you want to understand the energy of McKimson's cartoons, you just have to look at his two most popular creations — the loudmouthed rooster Foghorn Leghorn, and the Tasmanian Devil, a literal tornado of destruction. Other directors frequently only animated the most important parts of their characters, redrawing the eyes and mouths while recycling the same body, but McKimson's characters never stop moving.

And McKimson's responsible for some of Looney Tunes' most hilarious entries, like Rabbit's Kin where Bugs outsmarts a puma with an unforgettable wheezy laugh provided by comedian Stan Freberg, or Hillbilly Hare where, in one of the series' greatest extended gags, Bugs leads two hunters on a bone-crunching square dance across the countryside for half the short.

The end and after

As the '50s ran on, TV started cutting more and more into the theatrical cartoons' market share. Termite Terrace had already survived one scare at the height of the 3D movie fad in 1953, when studio head Jack Warner shuttered the studio for six months because he was convinced soon every movie would be in 3D and it would be too expensive to animate cartoons in the new process. When Chuck Jones joked that Warner predicted every child would be born with one green and one red eye, it's not much more ridiculous than the reality.

But as the '50s turned into the '60s, the budgets and profit margins kept shrinking. The animation studio finally shut down in 1964. But by the time the backlog of completed cartoons was used up, Warners decided they wanted to keep making Looney Tunes after all.

By then, most of the old staff had gone on to greener pastures. Friz Freleng had started his own studio, DePatie-Freleng, most famous for their Pink Panther series. Chuck Jones went to MGM, where he produced several TV specials, including his collaboration with Dr. Seuss on the holiday classic How the Grinch Stole Christmas! and his own feature film, The Phantom Tollbooth.

Warner Brothers commissioned DePatie-Freleng for new cartoons, mostly featuring Wile E. Coyote and the Roadrunner and the incongruous team of Daffy Duck and Speedy Gonzales. But the results disappointed audiences, and the revival only lasted a few years. The studio then returned to making its cartoons with an in-house animation studio, but that effort also petered out quickly. By the end of the '60s, it was over.

Back to the big screen

But as Elmer Fudd found out the hard way, ducks and wabbits are mighty hard to kill. Ironically, TV kept the cartoons alive after demolishing their theatrical profits, with reruns introducing them to generations of kids. Who Framed Roger Rabbit? brought an army of classic cartoon stars back to theaters in 1988. And it finally showed audiences what every cartoon-loving kid had always imagined: Mickey Mouse chilling out with Bugs Bunny and a fight between Daffy and Donald Duck.

The success of Roger Rabbit led its producer, Steven Spielberg, to pick up Tiny Toon Adventures, a TV series in which the classic stars mentored a new generation of cartoon critters. And a series of Nike commercials used Roger Rabbit's revolutionary techniques to film a basketball game between Bugs and Michael Jordan. Warners expanded them to feature length in Space Jam, introducing a whole new generation to Bugs and his friends.

Plans for Spy Jam, a sequel starring Jackie Chan, fizzled out, but they found new life as Looney Tunes: Back in Action. Warners hired director Joe Dante to oversee it. He certainly had the pedigree: He was Chuck Jones' close friend, inviting him to cameo in Gremlins and create new animation for its sequel. He'd even spent years trying to make a movie about Termite Terrace. Unfortunately, Back in Action's box-office failure seemed to be the end of big screen Looney Tunes... or at least it did until a Space Jam sequel starring LeBron James was announced in 2014 for release in 2021.

Looney Tunes on HBO

To promote the launch of their HBO Max streaming service in 2020, Warner Brothers commissioned a series of new Looney Tunes Cartoons exclusively for subscribers. While the thumbnail image of Bugs chatting on a cellphone suggests another modern update along the lines of Space Jam, the cartoons themselves are anything but: They painstakingly recreate the hand-painted look of the original shorts, and the new character designs call back to the characters' earliest appearances with touches like Sylvester's yellow eyes and snaggletooth. They even restore Daffy Duck's '40s persona as a zany trickster, which might confuse viewers who are used to seeing him as the ultimate loser.

The series attracted controversy for showrunner Peter Browngardt's decision to take away Elmer Fudd's shotgun. That turned out to be much ado about nothing; if you watched the cartoons without following the story, you may have never noticed. Any worries that this meant Browngardt wouldn't be true to the source material should be calmed by the cartoons themselves. They're faithful to a fault — except for a handful of anachronisms, they could have stepped right out of the '40s. If nothing else, they show that Looney Tunes are timeless. Whatever new incarnations appear in the future and however well they live up to their legacy, they and the original shorts are sure to entertain us for many years to come.