Things Only Adults Notice In Hotel Transylvania

Dracula would love to call his gothic boarding house a five-star destination, but the critical reviews for Hotel Transylvania suggested the place didn't offer much to scream about — at least not for adults. Rotten Tomatoes' Critics Consensus, however, suggested its "buoyant, giddy tone" would be great for the kids. But if critics' 45% approval threatened to put Hotel Transylvania in the grave, the 72% positive response from audiences raised the dead.

Hotel Transylvania is, after all, a family story about the struggle of letting your kids grow up. Perhaps parents were able to relive their own coming-of-age, finding comfort in the movie's wry but wholesome depiction of parenting. Not to mention, adults of all ages can pick out musical, literary, and scientific references as well as allusions to the social contexts of the world, all wrapped up like a mummy in the euphoria of a harmless fantasy.

Hotel Transylvania is about becoming "old enough." But it's also about, despite themes of immortality, never getting too old. There is always something new to learn about yourself and the world even when you're "older and wiser," and no matter your age, there is something for you in this movie.

This theme probably got stuck in parents' heads all day

Hotel Transylvania channels The Eagles' 1976 song "Hotel California." They even have the same number of syllables! And one of the song's most iconic lines states that "you can check out any time you like, but you can never leave." Similarly, vampires, mummies, ghosts, and zombies have "checked out" of the world of the living, but they can never leave their immortal life.

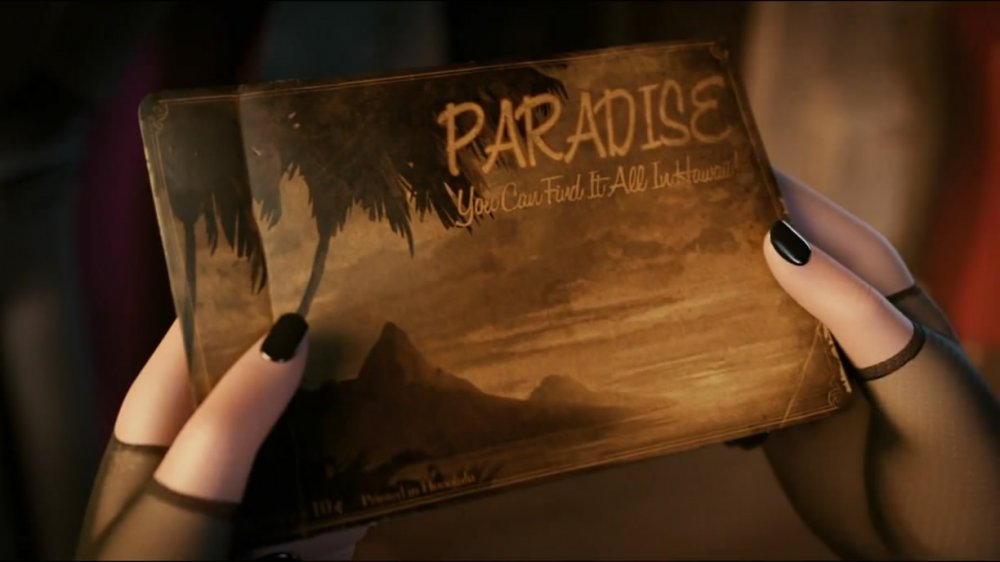

Mavis wants to go to the place her parents met in Hawaii: Paradise, which also alludes to the home of the eternal afterlife (if you're lucky). But "you can never leave" is also how Dracula feels about Mavis growing up and leaving home — to visit Paradise or anywhere else.

The song "Hotel California" also explores the theme of excessive indulgence in America, which parallels the savage picture Dracula paints of the humans in the outside world. He warns Mavis that humans steal candy from monsters, which is plainly a reference to the antics of Halloween night. In the real world, Halloween is sometimes deplored as symbolic of gluttony and greed; and the monsters clearly have a similar view of humans as hedonists. Hedonism itself is the pursuit of exactly what Mavis had set her sights on: "paradise," experienced as the perpetual pursuit of pleasure and happiness.

Debating color swatches at Lowe's possibly paid off here

In the beginning of the film, we see Mavis as a child, tucked into her crib and sleeping soundly. Dracula creeps up on her, and for a moment, we think he might be a threat. Really, he is just playing a game with his infant daughter. Dracula is an incredibly devoted, if overprotective father, generously offering plenty of quality time that consists of reading to his daughter, playing with her, and teaching her about the world and her own vampiric abilities.

Mavis' crib and enclosing curtains are cushy and purple, which can be read as symbolic not only of her father's overprotectiveness, but also of the dynamic between their personalities. Red is the representative color of vampires, lining the inside of their cloaks and their bloody teeth after a good meal. The color also represents "fierce energy," according to Bourne Creative, as well as passion, and love — traits that show prominently in Mavis' feisty personality and the fact that she wants to leave home to visit the place where her parents first fell in love.

But purple is the combination of red and blue, the latter of which symbolizes "calm stability," which Dracula desires for Mavis. He is obsessed with keeping her safe and refusing to let her leave the "crib" of her home and childhood. These competing interests serve as the fundamental conflict of the plot.

Parenting's a drag, even for the undead

Hotel Transylvania brims with endearing and inventive fantasy takes on the little details of parenting. Anyone who has ever changed a diaper would envy Dracula's ability to telekinetically suspend the dirty diaper in the air rather than having to touch it. And for disposal purposes, Dracula has a cute little diaper coffin, which opens with a foot pedal just like a diaper pail. This comic depiction of hands-free diaper duty likely had most parents drooling.

With his ability to turn into a bat and his use of this power to surveil his daughter, Dracula also gives new meaning to the term "helicopter parent." He even attempts to influence Mavis' interest in romance, commenting, "Sweetheart, there are so many eligible monsters out there." Most fathers would desperately try to steer their daughters away from the "monsters" of the dating pool.

And in an amusing but bittersweet exchange, Wayne Werewolf employs his children to track down Johnny the human, but the hyperactive pups have trouble focusing and obeying his request. Dracula solves the problem by inquiring which of Werewolf's children still respects him. The poor guy is painfully aware that filial respect wanes like the moon as children grow up, and knows exactly which one of his kids is young enough not to have reached that point yet.

The irony of working yourself to death (and back)

During the construction of the hotel, audiences might notice that all the construction workers are zombies, who, when you think about it, would make ideal workers. Or maybe it's the other way around, and the pursuit of being the perfect worker can turn a person into a zombie. Either way, many adults relate to the struggle of punching a clock and mindlessly toiling day in and day out, even past the point of exhaustion.

With zombies, though, there is no point of exhaustion. The undead don't need to sleep or eat, so they would never require a lunch break or a vacation day, though in Hotel Transylvania, they aren't portrayed as the completely inexhaustible labor source they would potentially provide in "real" not-life.

Exploring the extremes of zombies' possible utility is fascinating nonetheless. Without brains, they wouldn't complain, request reduced hours, or ask for a raise. If the bosses ever needed to expand the staff, they could just send the zombies out to infect "new recruits." And there would be no worker's comp claims and no need for the employer to take out workplace insurance, because the undead can't feel pain. Plus, they're rotting from the inside anyway, which probably qualifies as a pre-existing condition.

Frankie's selective fear of fire

Throughout the movie, Frankie (Frankenstein's monster) voices an intense fear of fire, imploring others to avoid situations that might expose them to it. He even has a plane phobia because engines can catch fire any moment. The hotel might seem like a safe place since it doesn't seem to rely on electricity, however, it employs candelabras and torches instead, which doesn't seem to bother Frankie as much as it should.

What only adults, and possibly high school English students, would notice is that this fear is actually canon: In Frankenstein, the 1818 novel by Mary Shelley, Frankenstein's creature is afraid of fire as well. He discovers that fire is deceptive: its illuminating power brings discovery and enlightenment, but it also has the capacity to harm and devastate.

The literally enlightening nature of fire parallels venturing into the real world as an adult, as Mavis desires to do. As you become an adult, you'll see so many new things, but you'll also take greater risks and face greater challenges and dangers. Sunlight is the bane of all vampires, and fire is also what killed Mavis' mother. This is part of the reason Dracula tries so hard to keep her in the dark. But on the other hand, the beauty of a glowing sunrise, which Johnny helps her see for the first time, is what inspires her to give humans another chance.

Mummy's farting problem doesn't make sense

Fart humor may be another culprit in the case of Hotel Transylvania's less-than-stellar critical reception. There are a number of silly moments that revolve around what is typically seen as childish comedy. This shouldn't necessarily detract from the film: It does need to appeal to children, after all, and it's not like the toilet humor pretends to be anything but. Except, one could argue, in one instance.

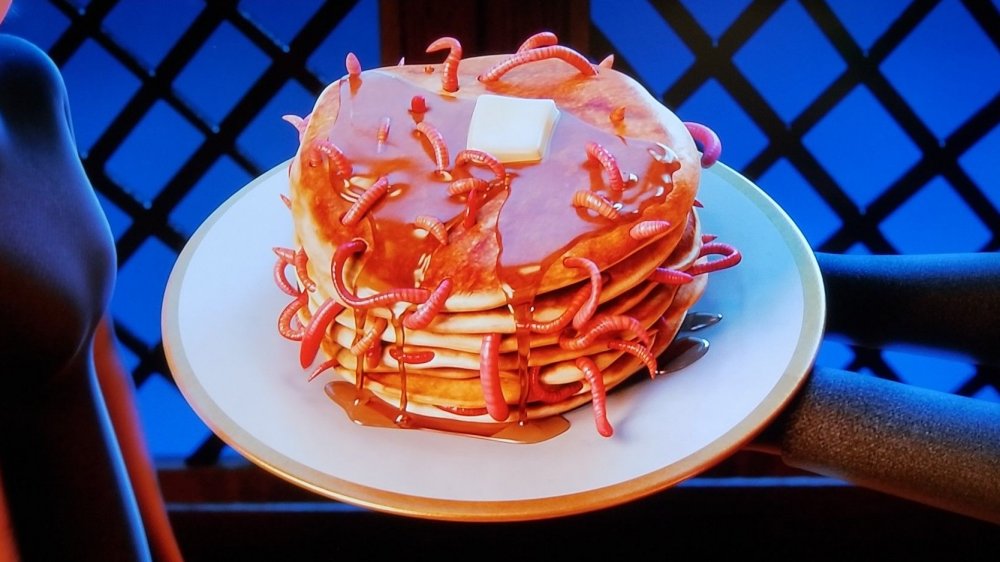

One particular gag, which literally makes characters gag, is when Frankie frames Murray (the mummy) for some foul flatulence, triggering many quips in the tired "it wasn't me" vein. But this joke actually has some level of science behind it. After the body dies, and before rigor mortis, most muscles actually relax involuntarily. That includes the bladder and bowel muscles, so something unsavory is bound to get out. When you think about it, flatulence is probably preferable to other potential escapees.

Mummification, however, is a seventy-day process meant to purify the body, including the removal of the intestines, stomach, and other internal organs, which are placed in jars, and entombed along with the body. Since Mummy has clearly left his resting place, it's safe to assume that the organs that would facilitate his farting issue aren't anywhere close by. So unless an embalmer really messed up, Frankie shouldn't have been able to pass the buck on passing that gas.

We live in a society

The "Hotel California" allusion isn't the only place where the theme of hedonism shows up, and adults may find certain commentaries on society quite familiar. The monsters keep a close eye on human affairs in order to remain apprised of emerging threats, which are always looming larger — literally. One of the most alarming developments is the fact that humans are "getting fatter." Health organizations throughout the adult human world are concerned about this trend as well, but for opposite reasons. Humans view it as a threat to their own wellbeing, but Dracula sees it as a menace to his kind. The bigger people are, the more easy it is for them to overpower monsters.

"Kids these days," many adults lament, are also shirking modesty and wearing less clothing. But rather than symbolic of a societal decline, as some members of older and even current generations of humans see it, in the eyes of monsters, this behavior actually makes people more powerful as well. It allows them greater freedom of movement to strangle monsters, or cut their heads open to put candy in (which they can then eat to grow to even more intimidating sizes!).

Coming-of-age jokes with a fundamental math problem

The supernatural world offers a lot of opportunities to joke about growing up that hold special meaning for those who have gone through it. The turning point of adulthood for immortal vampires comes at 118 years instead of 18. Of course, in terms of eternity, this doesn't make much sense: 18 is about a quarter of the average human lifespan, and although a quarter of infinity isn't technically possible to determine, it would probably be greater than 118, right?

Not to mention, the idea of immortality revolves around not aging at all. But non-aging would undermine the entire theme of the movie, so we won't worry about that. The joke is that there is a coming-of-age point for vampires that presents similar challenges to those of adolescent humans and their parents.

There are also a lot of one-liners that reference various recognizable points along the human path to adulthood. Mavis protests that she deserves independence because she is "old enough to drive a hearse." Another comment references Mavis being "barely out of training fangs," which could allude to anything from training bras to training wheels to braces. And in another plea for autonomy, Mavis points out that she's "not 83 anymore," because get it? That's normally very old!

Did you catch the clock?

By the time she turns 118, Mavis has prepared for a showdown with her father regarding her right to explore the world as an adult, which is why she is incredulous when she doesn't even get the chance to launch into her argument before her father agrees to her wishes. This seeming reversal surprises the audience, too, as Dracula has explicitly stated that he constructed the hotel in order to house his daughter forever with nary a reason to leave.

Of course, we find out that when he recommends a nearby human village to visit first, it's actually because the construction extends far beyond the hotel. The human village is a ruse: Dracula has enlisted a gaggle of zombies to pose as humans and play out every terror he warned Mavis about, hoping to scare away her desire to explore their world.

It works. Mavis flies away, frightened and disappointed. As she takes to the sky, it appears that the clock in the town square reads midnight (above). However, we don't hear any bells, which would align with the fact that the village is just a facade. Midnight is a significant hour in the spooky world, but it also signifies the transition to a new day, prompting an association with the new chapter of adulthood. The passage of one day to the next highlights the fact that time moves relentlessly onward, no matter how hard someone, especially a parent, wants to cling to the way things are.

What adult doesn't love grocery humor?

Although they call themselves monsters, the subjects of this film unsurprisingly define this term much differently from the way humans do. In fact, in their minds, the roles are reversed. They see humans as terrifying and dangerous savages with no morals and malevolent intent, but most of their habits and behaviors have clear analogues in the human world. The monsters have a sense of morality that humans would recognize, harbor no desire to hurt others, and place strong emphasis on family ties, social life, and loyalty. All in all, they're good not-people.

In fact, Dracula has adopted his own brand of veganism, even if this was only written for the sake of a one-liner that references his use of blood substitutes in place of killing and eating humans. Vegans in the human world use substitutes for all sorts of common ingredients, from eggs and butter, to lunch meat and cheese. Younger children who don't do their own grocery shopping or pursue alternative diets might not get that "Blood Beaters" is an apparent reference to the Egg Beater product. They also may not understand that this joke is a bit of a whiff, considering Egg Beaters is still "made from real eggs," only with the cholesterol-inflating yolks removed.

Is the real monster ... prejudice?

In instances like the Blood Beaters line and elsewhere, the likenesses between various aspects of human and monster life seem to primarily serve a comic function. But the equal worth of the lives of monsters and humans, obscured by the fear each group has of the other, offers a deeper look at the real dysfunctions of society.

The allusions to prejudice and xenophobia are fairly clear, as in this exchange between Dracula and Jonathan: Jonathan asks, "Are these monsters going to kill me?" Dracula answers, "Not as long as they think you're a monster," to which Jonathan replies, after pondering for a moment, "That's kind of racist." At the hotel, Jonathan is in the minority as the only human, surrounded by monsters, trying to blend in, in order to keep himself from harm. If looked at through the mirror-view of racial relations, which we admit is kind of an odd thing to do with an Adam Sandler-led kids' movie, the commentary here on what it's like to be a minority in America are just below the surface.

Mavis wants to forge a new kind of relationship with humans and acts against the fear-informed judgments she grew up with. Her father, a member of the older generation, believes it's not possible, but her persistence slowly changes his heart. The different cohorts of adults in the audience can take with them the lesson that sometimes the most threatening monsters lie in our individual and societal attitudes and behaviors.

Don't think to hard about the dismembered genealogy gag

Jonathan the human disguises himself and claims to be from Frankie's "right arm's side of the family." In Shelley's novel, Victor Frankenstein has discovered a way to bring life to dead matter, but rather than simply raise the dead, he wants to animate the ideal humanoid. As a result, he seeks out the most beautiful version of each body part. The most appealing face might not come from the same body as the ideal arm, leg, or hand, which is why each part sewn into the creature's form comes from a different person.

Obviously, each of these people has a different backstory and has left their own family behind, meaning that Frankenstein probably has a dozen or more sets of relatives. Shelley's creature never sought out his "ancestors," but it seems Hotel Transylvania's did. It's a little disconcerting to imagine that he is fully aware that he is made of the chopped-off body parts of a bunch of strangers, but on the more amusing side, we can visualize how these family ties would play out!

Frankie might drag himself to a staggering number of family reunions every year, but there's also the possibility that he celebrates a birthday every year for each of his components. Hopefully he receives birthday gifts from each of these sets of families – plus another set of presents on the anniversary of his creation.