Movie Moments You Completely Misunderstood As A Kid

Most kids' movies are just that: movies written for an audience of children. Because of this, they do their best to avoid including any subject matter that kids might have trouble understanding or that might be inappropriate for young viewers. That being said, there are rare moments in kids' films that are, for one reason or another, written to be something that only an adult would understand. We didn't catch these bits when we watched these movies as kids, but now that we've grown up a little, we've discovered quite a few moments in our favorite kids' movies that we have to admit we didn't totally get the first time around.

Often, these will be dirty jokes or other allusions to sexuality that are written such that most young kids wouldn't be able to spot them. They may also be references to news stories or pop culture from previous generations. But other times, they'll be a bit more understated, not a big and obvious hidden gag but rather a subtly multifaceted plot beat or bit of dialogue that we were unable to fully appreciate without the benefit of a fully formed frontal cortex. Join us as we revisit some selected moments from old childhood classics and see if you agree that when you rewatch a kids' movie with adult eyes, you often feel like you're watching a completely different film.

Shrek and Donkey speculate about the size of Farquaad's tower

Although it's ostensibly a film series for children, the Shrek franchise is famous for slipping in the occasional extremely dirty joke. We're just going to talk about one today, but just bear in mind that there's no shortage of options we could have chosen here.

When Shrek and Donkey first arrive in Duloc, the kingdom of the vain megalomaniac Lord Farquaad, they pause for a moment to take in the view. They turn their heads skyward to marvel at the enormity of Farquaad's castle, a towering vertical structure that dominates the landscape. After a moment's contemplation, Shrek asks Donkey, "Do you think maybe he's compensating for something?"

What exactly Farquaad is compensating for with his enormous tower, the film doesn't say. To be fair, there is technically a potentially non-lewd interpretation, as Farquaad is both highly prideful and deeply insecure about his height. So, if a child asks their parent what that line means, the parent might explain that it just means that Farquaad is insecure about being short. But c'mon, we all know what Shrek is really talking about.

"Hakuna Matata" is the opposite of The Lion King's true message

The 1994 film The Lion King is full of memorable musical moments. But without a doubt, the most earwormy tune of all, especially during a first viewing, has to be "Hakuna Matata." After the fairly dour sequence of events that the film just put us through, including the death of Mufasa, this upbeat musical number is just what the audience needs to pick their spirits back up. Timon and Pumbaa gleefully reassuring the grieving Simba that he shouldn't worry, and that everything will be okay, was undoubtedly what that sad little cub needed to hear.

All this being said, as the film goes on, an aspect of the story that totally went over the heads of most kids the first time around is that "Hakuna Matata" is, in truth, not the actual message of the film. In the long term, the real lesson that Simba needs to learn is not that he should just chill out and ignore his problems but rather that he needs to accept responsibility for his people. Even though he is filled with guilt for the part he believes he played in the death of his father, Simba needs to return home and face his demons head-on. "Hakuna Matata" is just a comforting lie.

Mrs. Potato Head mouths off in Toy Story 3

The approach that some kids' movies take toward appealing to the adults in the room is to do so covertly, by slipping in dirty jokes that only they will catch. Usually, Pixar films are above this sort of thing. They seek to appeal to adult audiences through just making a good movie that audience of all ages can enjoy, rather than by inserting secret sex jokes and pop culture references. That being said, even Pixar isn't above a bit of lewd wordplay now and then.

In Toy Story 3, there comes a point when our heroes are captured by the villainous Lots-O'-Huggin' Bear. In this moment, Mrs. Potato Head is one of the few toys who stands against him. While the others are silent, she starts screaming at Lotso, saying that she deserves some respect. To shut her up, Lotso angrily removes Mrs. Potato Head's detachable plastic mouth. Aghast, Mr. Potato Head steps forward and remarks to Lotso, "No one takes my wife's mouth except me."

We don't ever get an explanation about how exactly Mr. Potato Head "takes" his wife's mouth, and to be honest, we're not looking for one. But if this means what we think it means, then let's just say that we're happy to hear that the fire is still very much alive in the Potato Heads' marriage.

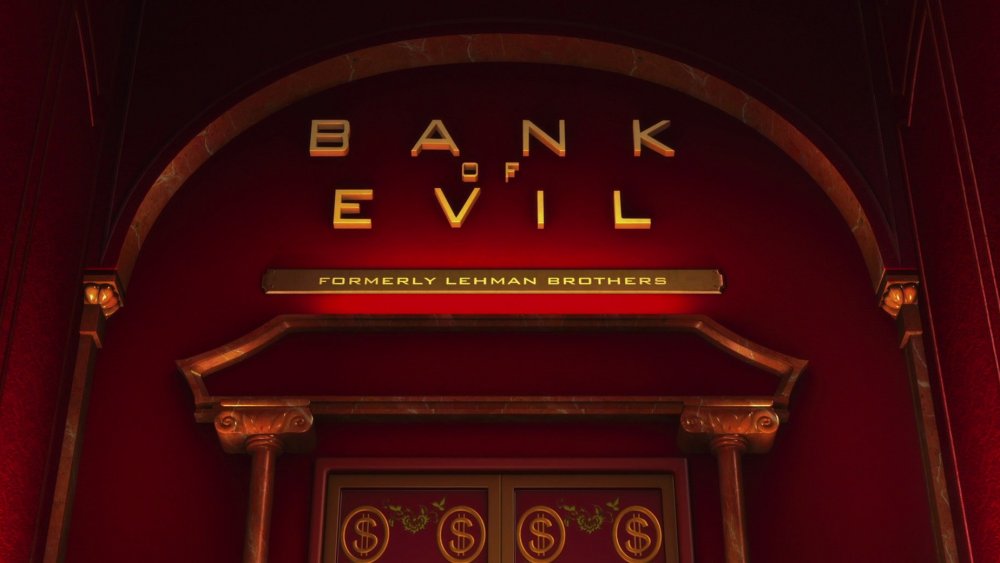

Despicable Me makes a killer joke about ... banking?

The film Despicable Me opens with the supervillain Gru getting some bad news. Apparently, some other unknown evildoer has just stolen the Great Pyramid of Giza, and this won't do at all. In order to one-up this new rival and prove, once and for all, that he is the greatest villain of all time, Gru decides to enact an even more audacious scheme: He is going to build a rocket and steal the Moon. In order to do this, Gru is going to need a loan, and in order to do that, he takes a trip to a secret, underground bank called "The Bank of Evil." As Gru enters the imposing, ornate structure, we see a small plaque underneath the name of the bank that says "Formerly Lehman Brothers."

This one definitely went over the heads of every kid in the theater, so let's explain. Lehman Brothers was a global financial services firm that was, at one point, the fourth-largest investment bank in the world. However, due to the firm's involvement in the events that led up to the subprime mortgage crisis of 2008, many blamed it as a major contributor to the worldwide recession that followed. It makes sense that, two years later, in a film about cartoonishly over-the-top evil, the writers felt like taking a parting shot at this much-hated, now-defunct firm, who some viewed as just as bad as any supervillain.

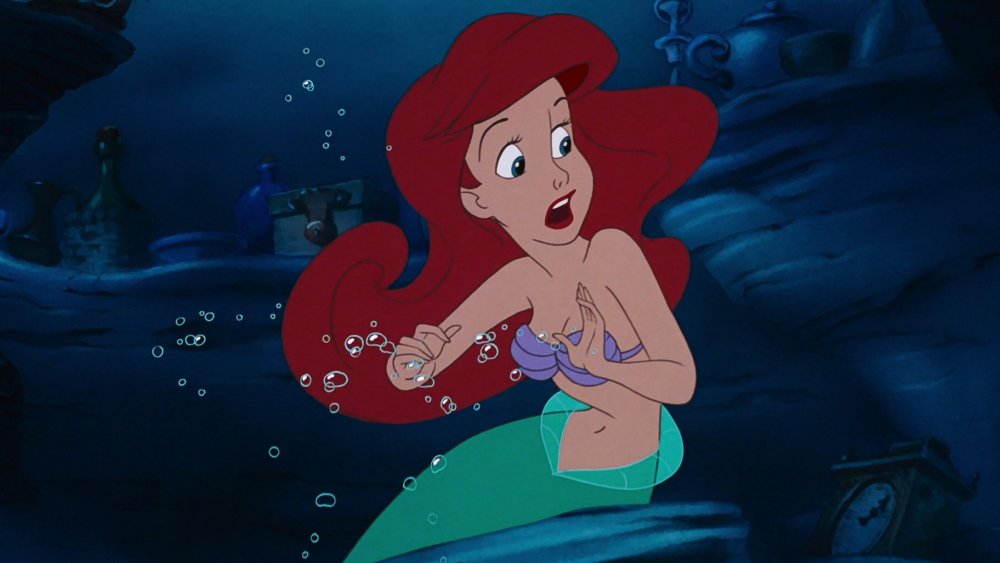

A line in The Little Mermaid contains a great amount of hidden depth

The Little Mermaid is undeniably a masterpiece, but it's also a relatively simple story. That's why it's so surprising that, when rewatching the film as adults, we found ourselves struck by a single throwaway lyric that is simply overflowing with subtext.

In "Part of Your World," Ariel is singing about how she's tired of living in the ocean, under the thumb of her overly controlling father, and she's fantasizing about all the ways the surface world must be better. Toward the end, she slips in, "Betcha on land, they understand. Bet they don't reprimand their daughters. Bright young women, sick o' swimmin', ready to stand."

With this line, Ariel is no longer just imagining having legs or feeling the sun on her skin, she's fantasizing about the ways that humans might be more socially progressive than merfolk. Given that this film is set during the 1800s, we know this isn't true, and that makes this already beautiful song even more heartbreaking. It's not that Ariel shouldn't want to become a human, or that it won't solve some of her problems, but she doesn't yet realize that it's not going to be an instant fix for everything in her life, as there are still many other hardships that she'll have to endure. Though, at many times, she is a remarkably wise character for her age, this is a moment in which we, as adults, can clearly see that Ariel is still just a kid.

Inside Out reveals that it's bear season in San Francisco

Inside Out tells the story of a young girl named Riley in a most unusual way: from inside her head. Our main characters are her various emotions: Sadness, Anger, Disgust, Fear, and Joy. From inside the control room within her mind, Riley's various emotions react to the world around her and argue about what's best for her.

At the beginning of the film, Riley's family moves from Minnesota to San Francisco, despite Riley's many protestations. When the family first arrives in their new home in the city, Riley's emotions are understandably overwhelmed. After a loud car with a rattling engine passes by outside without warning, Fear begins to freak out, saying, "What was that? Was it a bear? It's a bear!" Disgust reassures him by saying, "There are no bears in San Francisco." Anger then chimes in by saying, "I saw a really hairy guy, he looked like a bear."

Kids might think this is just a joke about a big, hairy guy, who kind of looks like a bear, but more adult viewers would realize that there may also be a second meaning to Anger's observation. In the LGBT community, "bear" is a slang term for a large and hairy gay or bisexual man. We're not 100-percent sure that this second meaning was intended by the writers, but especially in the context of San Francisco, a city known for having a rather vibrant queer community, we find it hard to believe that this little bit of wordplay was unintentional.

Josie and the Pussycats' satirical product placement went way over everyone's heads

When Josie and the Pussycats first came out, no one knew what to do with it. The film tells the story of an unknown band, the Pussycats, who are plucked out of obscurity one day by a devious record executive and thrust to superstardom. Once they become stars, however, the band begins to discover evidence of a truly ludicrous government and corporate conspiracy to control the minds of young people through subliminal messaging in pop music.

This highly stylized comedy was meant to be a satire of capitalism and celebrity culture, but at some point during the marketing and critical reception, that all got lost in translation. Kids who went to see it were too young to understand what the movie was trying to do, and adults, thinking it was a dumb kids' movie, dismissed it entirely and ruthlessly criticized the film's ubiquitous product placement. Making matters worse, because the initial theatrical run of this PG-13 "kids' movie" bombed so dramatically, the studio recut it for a PG rating and released a version on home video that was explicitly marketed as family-friendly.

Flash-forward to the 2010s, and suddenly, it clicked. After an internet-wide critical re-evaluation, the verdict is in: Josie and the Pussycats is, and always has been, a hilarious and insightful critique of the entertainment industry, and all the egregious product placement was very much on purpose. Turns out the film didn't need to grow up — we did.

"Hellfire" in Hunchback of Notre Dame gets extremely dark

Disney canon is no stranger to potentially disturbing subject matter. That being said, perhaps the darkest moment in any Disney film is one that we couldn't have fully understood as kids. Let's talk about "Hellfire," Frolo's song from The Hunchback of Notre Dame.

Throughout the film, Frolo's goal is as dark as it gets in a kids' movie, or any movie. He's committing genocide, working to eradicate the Roma population of Paris. Opposing him is Esmeralda, a young Romani street performer who has repeatedly eluded his grasp. But when Frolo finally manages to get his hands on Esmeralda, we start to get a sense that he's interested in her for ... other reasons as well. While she is restrained, he sneaks a sniff of her hair, and he takes her silk scarf, which we later see him sensually rubbing across his face.

That brings us to Frolo's song. Frolo gazes into his fireplace, contemplating his own sinful desires. He blames Esmeralda for tempting him and then alternates between fantasizing about her sexually and fantasizing about burning her to death. This includes lines such as, "Choose me or your pyre. Be mine or you will burn." Sure, we knew the scene was bad back when we were kids. Frolo is the villain, and he's singing about Hell. But it's only by looking back on that scene with adult eyes that you can really comprehend the totality of what he's really saying and just how horrific it truly is.

The Genie's endless celebrity impressions were way too old and obscure for most kids

When 1992's Aladdin first came out, it was a smash hit with kids. A large part of that was due to the character of the Genie, voiced by Robin Williams, who was constantly delivering jokes and doing celebrity impressions. That being said, a fair percentage of the Genie's impressions were almost certainly going way over the heads of the film's young audience, as they were mostly old celebrities from previous generations of Hollywood. Let's run them all down and see how many you caught.

When the Genie is first introduced, he does rapid fire-impressions Arnold Schwarzenegger, Señor Wences, Ed Sullivan, and Groucho Marx. Then, during "Friend Like Me," some of his dance moves are based on Cab Calloway. After the song, Genie also delivers impressions of Peter Lorre, Robert de Niro, and, strangely enough, American conservative author William F. Buckley.

Once our heroes escape the Cave of Wonders, the Genie does back-to-back impressions of Carol Channing and Arsenio Hall. Then, during "Prince Ali," the Genie's old man voice is an impression of actor Walter Brennan, and his newscaster persona is based on Mary Hart. Later in the film, he also slips in some quick impressions of Rodney Dangerfield and Jack Nicholson. We think that's all of them, but given that most of our writing staff wasn't alive when most of these celebrities were at their peak, there's a nonzero chance we may have missed a couple more somewhere.

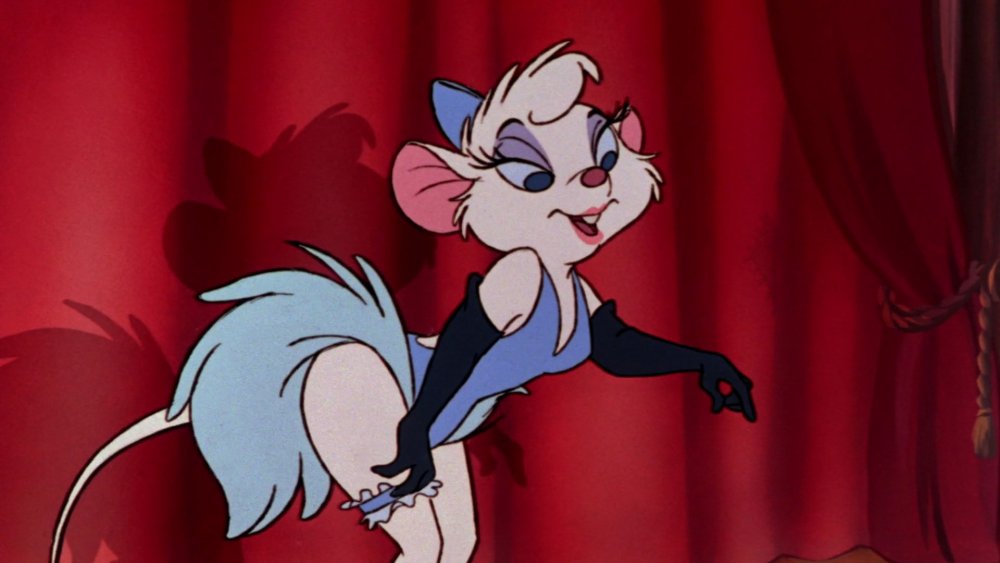

The Great Mouse Burlesque Dancer

The Great Mouse Detective is somewhat of a forgotten entry in the Disney canon, so there's a fair chance you missed this one entirely. But even if you did see it, we're willing to bet you've completely forgotten about a totally unnecessary scene in the middle that would probably be best described as ... confusingly horny?

The film takes place in a secret world of mice living alongside humans in late 19th-century London. At one point, as Basil, our mouse detective hero, searches for a missing person, he visits a shady little mouse bar called "The Rat Trap." Once inside, as he sips his mouse-sized pints and scans the crowd for suspicious characters, he is treated to a stage show.

A young mouse woman comes onstage and begins to sing a song called "Let Me Be Good to You." Midway through the show, she removes her dress, revealing some light blue lingerie, and she begins to dance around the stage. Kids may think she's just singing and dancing, but any parents who are watching will realize that this is, in fact, a burlesque show.

Perhaps the raciest it gets is when she says the line, "Hey fellas, I'll take off all my blues. Hey fellas, there's nothin' I won't do, just for you." Given that she's currently wearing blue lingerie, we can guess what she means by taking off her blues. What on Earth this scene is doing in a movie made for eight-year-olds is anyone's guess.

Who Framed Roger Rabbit references a real-life conspiracy theory

Throughout Who Framed Roger Rabbit, our hero Eddie Valiant slowly discovers that the villainous Judge Doom is at the heart of a city-wide conspiracy that is equal parts diabolical and impenetrable. He is the "sole stockholder" in a transit company which has purchased the city's streetcar program so that they can dismantle it and then profit off constructing a vast highway system. If you were a child the first time you saw this film, you not only wouldn't know what any of this meant, but you wouldn't know it's based on some real history, or at least some real conspiracy theories.

It's true that, in 1945, a company called National City Lines purchased the Los Angeles Railway, and over the following decades, the streetcar system was phased out in favor of buses. It's also true that the principal investors in National City Lines were General Motors and other auto manufacturers. That all sounds extremely bad on paper, so it's easy to see why some believed that this was all a deliberate secret plan by the auto industry to kill the thriving streetcar network.

However, this theory misses a key point of history, which is that the Los Angeles railcar system was absolutely terrible. It was slow, unpopular, difficult to maintain, and already had one foot in the grave when it was sold off. Though corporate greed is definitely responsible for a high percentage of real-world evil, in this particular case, it was more of a lack of vision, government funding, and public interest that killed the LA streetcar.