The Biggest Plot Holes In Alien Movies

Movies involving aliens depict scenarios that, as far as we know, are pretty much impossible. This is what gives them their allure — but that doesn't mean we don't expect them to preserve a logically consistent internal structure. The "science" and "fiction" elements of the genre are equally essential to the execution of a compelling piece of entertainment: Audiences need their flights of fancy to be built upon a foundation that makes sense.

Alien movies, though, often tackle such ambitious ideas that a couple of plot holes here and there are inevitable. When it comes to many of these goofs, fans can either ignore them or conjure up plausible explanations that honor their love of the film. That's a feat in and of itself: Not everyone can make a movie fans want to believe in, even when it's hard. But when one of these movies falls short of its potential in an irredeemable way, eagle-eyed viewers are quick to notice. The only battles more intense than the intergalactic wars waged in these movies are those fought in sci-fi forums over their discrepancies. These are the biggest, most blatant, and most frustrating plot holes in movies about aliens.

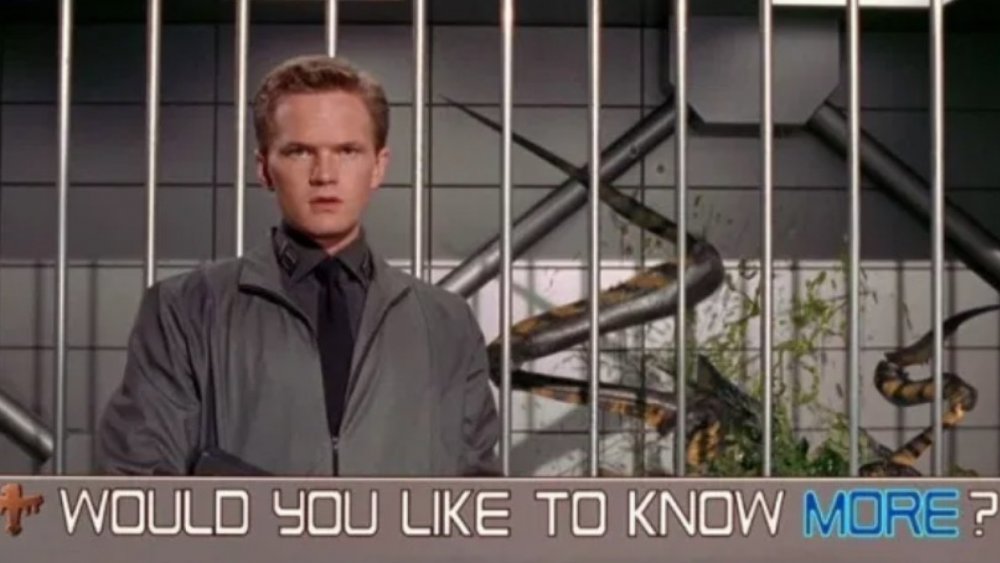

Missing the target

1997's Starship Troopers imagines an Earth 700 years in the future. By this point, humanity has developed and mastered incredibly advanced technology. And yet, despite this uber-tech and the exalted position the military holds in this society, it takes the entire movie for the defensive forces to come up with an effective strategy against the extraterrestrial race known as the "Bugs."

Or hey, perhaps it doesn't: Carl Jenkins teaches viewers in a newsreel that if you aim for the nerve stem, you can kill a Bug in under 10 shots. He even demonstrates this on camera. Yet it takes multiple soldiers, and substantially more bullets, to take down any of the other Bugs in the film. Moreover, these mooks fire at any and all Bug body parts. Did the military simply ignore Jenkins' nugget of wisdom? Another possibility exists: The Bugs might not really be as easy to kill as Carl makes them seem. After all, the one he dispatches on film is confined to a cage. But if this is the case, one would expect this highly militarized society to send tanks or some other more durable, aggressively weaponized force, against the Bugs, rather than singular gunmen.

Modifying DNA vs. modifying reality

The issue many fans take with District 9 doesn't have to do with a confounding Easter egg or an overlooked loose end, but with an overarching fact of the story. There is, simply put, little to no effort put towards involving science in the premise of the 2009 movie. It is frankly outrageous to propose that the alien "Prawns'" extraterrestrial DNA would be so compatible with that of humans that it could intermingle, much less change human anatomy shortly after exposure. Yet that's exactly what happens — our protagonist Wikus even grows a claw overnight.

The incredulity of a discerning audience mounts when we consider the long and complex history of genetic modification in our own world, and compare it with the ugly but relatively seamless course of Wikus' mutation. There is also no rhyme or reason to the human psychology Wikus retains. He just seems to keep his mind for the sake of preserving his motivation, and thus the trajectory of the plot. Why is his human brain affected considerably less than his physique? Aren't the differences between crustacean brain structures and our own just too vast to bridge? Apparently not.

On the subject of his physique, it's a serious lapse in MNU's security for Wikus, a former-operative-turned-fugitive of the company, to still have his fingerprint security clearance on the books, allowing him access to secure areas.

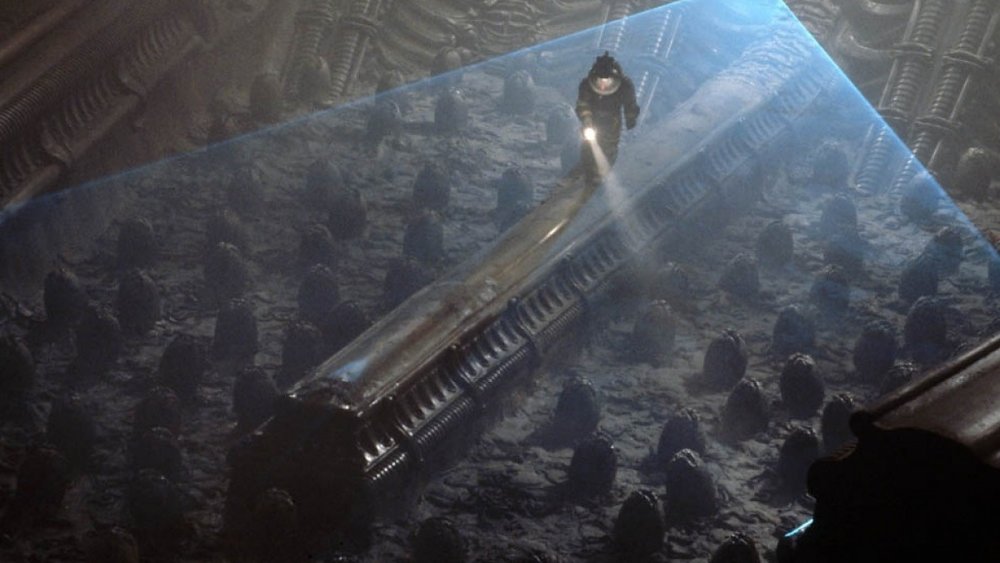

Easter "egg"

There is no satisfactory explanation for where the egg on the spacecraft Sulaco in Alien 3 comes from. Cue dozens of confused forum posts on the subject of the 1992 three-quel. Much conjecture has arisen, with varying degrees of probability. Two particular theories have gained notable traction: That Bishop the android carried a few eggs with him, or that the Queen laid the egg in 1986's Aliens.

The Bishop explanation contradicts James Cameron's depiction of the android as a trustworthy guy, of course. But still, this is the theory that suffers from the fewest direct conflicts. There is no evidence that this happened, but little standing in its way. None of the Queen theories, on the other hand, hold up when examined against the established biology of the Xenomorphs and the timeline of the franchise. The Queen on the Sulaco cannot lay eggs, because her egg sac was ripped from her in Aliens. Even if, somehow, she could regenerate the sac, or adapt in order to generate an egg and force it out, it would take much more time than what elapses before she is ejected from the dropship in that film.

Over-explanation can be just as bad as under-explanation

The Alien franchise doesn't just struggle with under-explanation — it outright suffers from it. A particularly major plot hole is created in Alien: Covenant, which seeks to connect 2012's Prometheus to the original franchise.

The original events of Alien begin when the crew of the spaceship Nostromo intercept a distress call from the planet LV-426. There, they discover, onboard a crashed spaceship, thousands of Xenomorph face-hugger eggs. They also discover the Space Jockey, a large humanoid from whose chest an alien apparently burst, killing him long before the crew's arrival.

In the sequel, Prometheus, we learn that the Space Jockey was actually a spacesuit for the Engineers who created humanity and subsequently destroyed the population of Earth 2000 years prior, taking all but their own with them in the process. This history means that the ship must have crashed into LV-426 centuries, if not millennia before its discovery in 2122. In Covenant, however, we learn that the android David's scientific curiosity and meddling resulted in the creation of the eggs, and that this happened in the 11-year gap between Prometheus, which took place in 2093, and the events of Covenant in 2104. Based on this timeline, there should have never been eggs on the "derelict" spacecraft, and Alien should never have happened.

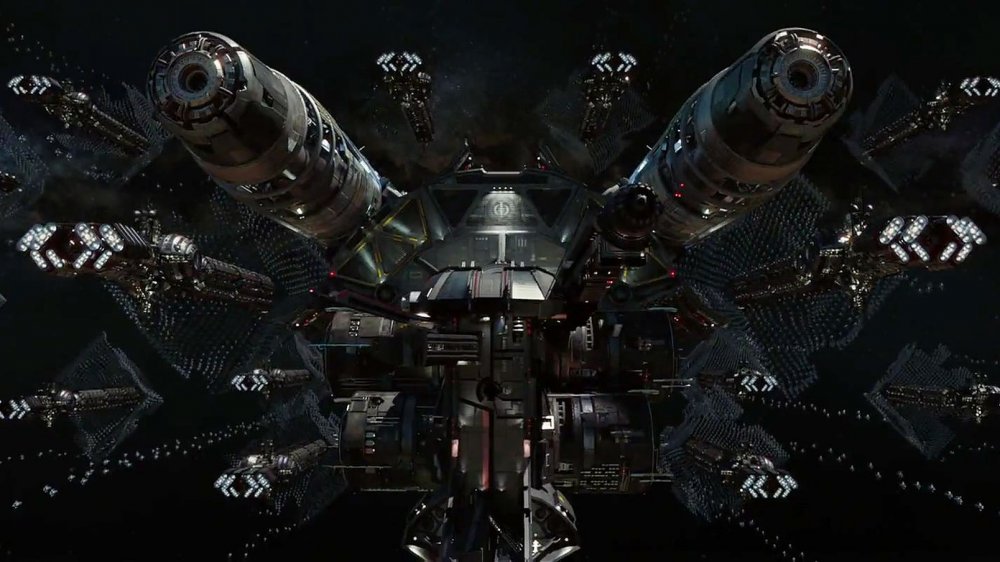

Destroyer of worlds ... or plots?

Ender's role in the 2013 Ender's Game movie is completely irrelevant, which raises some pretty significant issues for a story that centers around him and his remarkable combat skills. How could he be so useless? Well, as it turns out, humanity doesn't really need a child prodigy who can finesse their way out of destruction. All that's really needed is one decent-enough leader and one great weapon: the Molecular Disruption Device.

The MDD can completely disintegrate matter, and while it loses potency as it disperses, if it encounters more molecules, the dispersal process starts over. Basically, the device is an unstoppable world-destroyer, as a world is itself just a conglomeration of molecules. The device is heavily protected: In the final showdown, Ender orders most of his vastly outnumbered fleet to sacrifice themselves to guard the MDD until it can fire on the Formic homeworld. It does what it is designed to do, annihilating the entire population of the planet. So in theory, all humanity ever needed was someone to call the shots on pressing the button. Couldn't this have been anyone?

Cowboys and aliens (and pirates?)

The invaders in Cowboys & Aliens stop by Earth on their tour of destruction, having ravaged at least one other inhabited planet that we know of. Apparently, their mission is to travel the universe in search of gold, which sort of makes them interstellar pirates. It also means they have something in common with humans, as the 2011 film takes place shortly after the end of the California Gold Rush. We don't know why they want gold, but it's likely not because they use it as currency. Gold can conduct electricity and transmit digital data, form alloys with other metals, and help shield from radiation.

Not only would it be useful to an alien race in this manner, gold is also part of the composition of many cosmic objects. In fact, gold on earth is theorized to have been brought to the planet by asteroids. But because of this, it would actually be a much greater, and arguably prohibitive, effort to harvest gold from Earth and then expend energy to propel it back into space. The aliens could just as easily have extracted gold from a more amenable source, somewhere in space. And they wouldn't have risked an epic cinematic showdown with Earth's inhabitants, either.

Read the signs

When the news reports that someone has discovered "a weakness" of the invading aliens in 2002's Signs, it's treated as a big secret. For some reason, this information isn't immediately shared with the world — only the fact that it exists is made widely public. This is especially surprising, since the mysterious weakness is water, one of the most abundant resources available on the planet.

Aside from the moral imperative to share such crucial information, it's inconceivable that none of these aliens would have encountered water already, simply due to ubiquity and chance. If they ravaged homes across the country, wouldn't one of them have burst a pipe at some point? What about the water that composes the majority of the human body? What about backyard swimming pools? Heck, what about ambient humidity?

It's even stated earlier in the film by Ray, the man responsible for the traffic accident that killed Graham's wife, that he heard they don't like water. Where did he hear this from, and wouldn't people have immediately jumped on that lead, just to see if anything came of it? The introduction of the mysterious weakness is supposed to be some sort of Chekhov's gun, but is really just a reason the movie should have been a lot shorter.

10 Cloverfield Lane falls 20 proof short

Crucial plot points in 10 Cloverfield Lane rest on flawed science. For one thing, the water table in Louisiana is so high that the bunker's existence is seriously unfeasible — not to mention the fact that the city is, in fact, sinking below sea level. The frequent hurricanes and almost yearly flooding of the Mississippi River exacerbate this effect, causing the water table in the delta to fluctuate wildly. If the homes of New Orleans and greater Louisiana are at significant risk of flooding when levels rise, an underground bunker — where most of the film takes place — would have a lot of trouble surviving.

Another one of the movie's scientific inaccuracies revolves around the fictional Scottish whiskey Michelle uses for a Molotov cocktail, which is often touted as evidence of the film's attention to detail. It's actually an instance of the exact opposite. When this particular attempt at creating a Chekhov's gun appears, the camera lingers for a strikingly long moment on the bottle — long enough for us to see that it is a 27-year-old scotch weighing in at 80 proof. Whiskey can be flammable when its alcohol content exceeds 50%, or 100 proof, which means she couldn't have actually used this bottle to destroy the alien spacecraft.

The sound of silence

While John Krasinski's 2018 debut film A Quiet Place offers a creative take on alien and horror films, viewers raise the same plot complaint again and again: Humans make a ton of involuntary noise throughout the day. The Abbotts absolutely would have been discovered at some point in the film. Perhaps if more of the questions regarding the silent life of the family had been addressed, the naysayers would be appeased. But the fact that there are so many potential loopholes to begin with points to the real implausibility of evading this particular type of predator for so long.

One of the most glaring problems is that Lee starts a fire every night. Fires almost invariably make noise for a variety of reasons, from the crackling of air being released as the cellulose in wood converts to gas, to the toppling of the wood itself as different parts burn at different speeds. And the family would face even simpler challenges too, as basic as learning to burp silently or hold in a sneeze.

Assuming the characters have the wherewithal to come up with solutions for these basic, sound-making aspects of human life, there's another snag. Why don't they settle next to a source of running water, since this is shown to mask the sound of speech?

Putting the "extra" in "extra-terrestrial"

One of the most iconic scenes from 1982's E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial is the moment E.T. and Elliott soar through the sky on a bicycle, propelled by the alien's science-fiction abilities. We discover that he can grant the power of flight (and also bring an audience to tears, but that's another matter) simply by lifting a finger. It's a heartwarming moment when he and Elliott share their flight earlier in the film, and a triumphant one when E.T. uses this power to help the group of friends escape the authorities along with him later on.

The magic of these scenes is undeniable, but they do beg the question: If E.T. can fly, why didn't he use that power to escape earlier and save everyone a lot of hassle? Especially considering that his strength wanes the longer he remains on Earth, and that this reduces his capacity to defend himself or escape, it's surprising that he doesn't take the opportunity to use his powers when the earliest threats present themselves. Maybe his sentimental attachment to Elliott makes him stay put a little longer –- or maybe he just lives for the drama.

A tremor in time

Adding sequels and prequels to a successful film can be a double-edged sword. On the one hand, the producers can clear up any misconceptions and perceived plot holes through retcons. Weighing down the original installment with hefty exposition can threaten the viability of spawning a popular franchise, after all — why not tuck it into the sequel instead? On the other hand, though, diving too deep into the backstory of original events can make things even more complicated and confusing.

Tremors 4: The Legend Begins, released in 2004, evidences this problem. The first Tremors film reveals that the town of Perfection was established in 1902 -– but the 2004 prequel, in which the town of Rejection is resettled as Perfection, takes place in 1889. You can argue that this oversight makes the entire series impossible, but if you're in kinder spirits, you can chalk it up to some sort of clerical error in the settlement's record-keeping.

Sleeping on the job

It's especially disappointing when a would-be shocking twist turns out to have a major hole in it. The plot issue in this 1956 film screws with everything, starting with the title: Invasion of the Body Snatchers. The idea the film rests upon is not that alien invaders are snatching minds, but rather that they are snatching the bodies of people on Earth and replacing them with identical-looking alien impostors. The characters in the film start finding these duplicates, so we know that the aliens aren't taking over the minds of existing bodies.

This makes the twist at the end, when Becky falls asleep for a few moments and wakes up as "one of them," to the horror of love interest Miles, a lot less compelling and way more confusing. She only falls asleep for a second before awakening as a pod person. It is never specified what happens to the original bodies, but we know that a switch is required. Yet in Becky's case, for some reason, this all goes out the window. The shock factor isn't enough to distract from the nonsensical deviation from the movie's established rules.

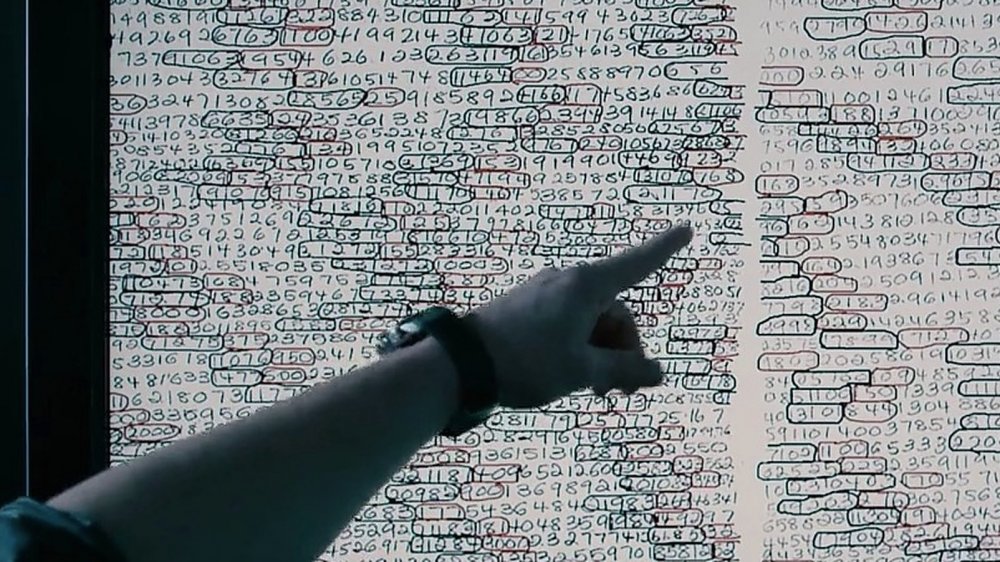

Ignorance is bliss

There's not enough Knowing going on where it counts in 2009's film of the same name. The plot of the movie, set in the year of its release, rests on the scribbles of Lucinda Embry, a child who is guided by voices to write down a series of seemingly meaningless numbers as her contribution to a time capsule 50 years earlier.

The child of John, an MIT astrophysics professor, receives her letter when the time capsule is opened in 2009. John realizes that the numbers are a code, predicting the exact dates and death tolls of major events since 1959. Three events remain, with one set for the following day. John then discovers that Lucinda's code contains the coordinates of the events as well, which could be crucial in preventing them.

However, the coordinates in Lucinda's letter don't specify cardinal directions, so they could have referred to any one of four points on Earth. Yet John assumes these numbers refer to north and west, without any basis. He must just be incredibly lucky, because one set of coordinates corresponds to the place where interstellar beings are leading children onto cosmic arks that will transport them away from Earth before a solar flare destroys all of humanity. Ignorance would not have been bliss if he had been wrong about that.