The Most Bizarre Ways Movies Got Funded

Seldom is the phrase "no-budget film" meant literally. All films, even modern ones shot on iPhones, have some expenses. It's a sure bet that every movie you've ever seen in a theater, on TV, or on a streaming platform incurred thousands of dollars in costs, if not millions. Even if production itself is free or involves outright guerilla filmmaking, it costs money to distribute and market.

Much as it seems otherwise in Hollywood, there's not an infinite supply of money — especially not normal, clean, legitimate money. So, filmmakers pushing their passion projects often have to find funding from unusual sources. It's not unheard of for, say, casino owners or shady characters to have a financial interest in a movie. But that only scratches the surface of what we're talking about here. Some people have gone to absurd lengths to up their budget, sometimes even taking part in weird rites of passage to appease investors. Other times, unusual sources bankroll and produce the movie on their own. Here are some of the weirdest cases we could find.

George Harrison bankrolled The Life of Brian

Monty Python's Life of Brian had a hard time getting funding, with many deeming it blasphemous or obscene. Eventually, the comedians found a partner in EMI ... who read the script days before production was scheduled to start, rejected it, and pulled all funding. As The Guardian put it, that's when Eric Idle decided to call "the richest person he knew" — George Harrison of the Beatles.

The Beatles were all Python fans, and Harrison in particular struck up a friendship with Idle. The guitarist consulted with his business manager and agreed to put up £2 million, a shocking amount at the time, even for an ex-Beatle. Harrison remortgaged his mansion, and his business manager remortgaged their office, and they used the money to set up the production company HandMade Films, specifically to make Life of Brian.

Harrison put up the money for two reasons. First, he said that Monty Python "kept him sane" while the Beatles were breaking up, so he felt he "owed [them] one." Second, as reported by The Guardian, he "liked the script" and "wanted to see the movie." Sure it was, in his own words, "the most expensive cinema ticket ever issued," but how was he going to watch the film if he didn't put up the funding for it? He even appeared in a small role. Life of Brian was a massive box office success, and HandMade Films went on to become one of the most influential British production companies of the 1980s.

The Room was funded by ... good question, actually

The Room is a disasterpiece on its own, endlessly rewatchable both in spite of and because of its awfulness. The behind-the-scenes story of it is just as compelling, spawning a book, a movie, and a documentary that Tommy Wiseau himself tried to block. There are also two questions about the film that people have been chipping away at for years. Why did The Room cost $6 million to make, and where on earth did Wiseau get $6 million in the first place?

Wiseau never revealed where he got most of his budget, but he claims that he was preparing and saving money for some time. He revealed to Entertainment Weekly in 2008 that some of the money came from clothing imports, stating, "We import from Korea the leather jackets that we design here in America." Actor Greg Sestero has relayed another possibility, saying that Wiseau claims he made a fortune off flipping real estate in San Francisco, a claim Sestsero doesn't buy.

Of course, there's one other theory — he hijacked Northwest Orient Airlines Flight 305 in 1971 and jumped out of it with a briefcase full of money. That's right. Tommy Wiseau may or may not be D.B. Cooper. Wiseau himself denies it, but he's famously unreliable. It's real if you, dear reader, believe it.

Plan 9 from Outer Space was funded by Baptist clergy

Plan 9 from Outer Space is the platonic ideal of a bad movie, one of the worst sci-fi movies ever made, and the most famous film of Ed Wood's ignoble career. But the funding for a movie about grave-robbing aliens came from an usual source — Baptist clergy.

J. Edward Reynolds was a Baptist minister in California and was also Wood's landlord. Reynolds had long wanted to make a movie about evangelist Billy Sunday. As such, Wood approached him with a proposition. If Reynolds funded Grave Robbers from Outer Space, they'd use the profits to make a Billy Sunday movie. Reynolds agreed, with a few conditions. First, he wanted Wood to change the sacrilegious title, hence Plan 9 instead of Grave Robbers. Second, he wanted the cast and crew to receive full-body baptisms, an event that saw actor Tor Johnson fake drowning to get a rise out of the crowd.

Convinced, Reynolds put his money behind the project. He created a production company, Reynolds Pictures, and convinced fellow ministers to invest. One such minister was Rev. Lynn Lemon of Tulsa, who gave $500 off his life insurance policy and got a small part officiating a funeral. Reynolds himself appeared in the movie as a gravedigger. The movie obviously never made a profit — Lemon only got $80 back on his investment — and that Billy Sunday movie never got made. It did, however, bring notoriety to those involved.

Katalin Varga was made on inheritance

Peter Strickland is one of the most acclaimed British independent filmmakers. His first feature-length movie, Katalin Varga, burst onto the festival circuit in 2009 and left a lot of people wondering where this Strickland guy was all this time. He was always there, but he just needed some surprise funding to get his first film done.

Strickland made a couple short films in the '90s before retreating into a series of dead end jobs. After his late uncle's house was sold around 2006, Strickland was given a £25,000 inheritance. Everyone told him just to just invest in some property, but he decided to move to Eastern Europe and make a movie. He went to the Romanian countryside and shot his film in 17 days.

The cash ran out after production, and he lost his day job, moving back to England in 2007. He had a hard time getting temp jobs, and Strickland resigned himself to the idea that his movie would never get made. However, he eventually scraped together enough money to get the movie done in 2009, and it won critical acclaim. He doesn't look back on this time all that fondly, telling The Guardian, "Though it would be easy to romanticize the memory, the truth is it was horrible. I was glad to see the back of it."

The Spitfire Grill was funded by the for-profit arm of a Catholic charity

The Spitfire Grill is a whole series of contradictions. It's a semi-religious film written and directed by a Jewish man, funded by the for-profit arm of a Catholic charity.

The story starts with the Sacred Heart League, the aforementioned Catholic charity. They initially gained fame through their "drive prayerfully and carefully" campaign, where they provided dashboard Jesuses to promote safe driving. They later grew and started building schools, offering meals, and sending out religious literature. By 1985, they decided to get into media productions and were soliciting scripts by the early '90s. To facilitate this further, they created a for-profit arm of their charity, Gregory Productions. And after getting their hands on Lee David Zlotoff's The Spitfire Grill, they had their first project.

The Spitfire Grill screened at Sundance, where it was warmly received and won the Audience Award. A bidding war opened up, with Castle Rock winning at the price of $10 million. When asked about the religious leanings of the production company, a Castle Rock executive said the Sacred Heart League's activities seemed decent. More importantly, the film was an asset, not part of an ongoing relationship. As they told The New York Times, "We're not promoting the Sacred Heart League. We bought a movie, and our job is to sell it as entertainment."

The movie didn't land as well with the critics or the general public as it did with the Sundance audience, but that was $10 million dollars in the Sacred Heart League's coffers, which was used to help build a school.

Inchon was funded by the Unification Church

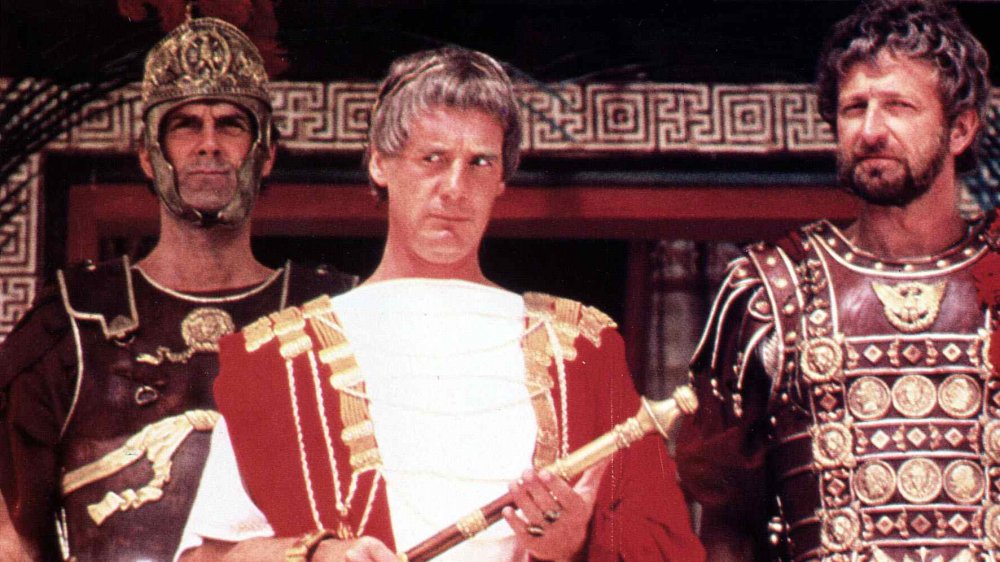

Inchon is one of the most notorious bombs in cinema history, one that was both critically reviled and a box office disaster of historical proportions. The specifics of this movie's production have been written up many times, and central to Inchon's mythos is its funding, as the movie was backed entirely by the controversial and cult-like Unification Church.

Funding for Inchon — which started with a budget of around $18-$20 million — was originally put up by Mitsuharu Ishii, a Japanese newspaper publisher. His involvement raised some eyebrows given that his newspaper was owned by the Unification Church, but he insisted that he was merely a member. As such, he got some A-list talent aboard. Laurence Olivier starred as Douglas MacArthur, and the cast included Ben Gazzara, Jacqueline Bisset, and Toshiro Mifune. He even got the Department of Defense to consult. Olivier in particular made out like a bandit. He was paid $1 million for the role, which multiple accounts report was partly delivered via helicopter in a suitcase full of cash.

Eight weeks into production, the truth was revealed. Cult leader Sun Myung Moon, head of the Unification Church, was the one supplying most of the money. Many of the cast and crew said Ishii lied to their face about the funding, and they never would've signed on if they'd known the truth. The Pentagon faced protests, and dignitaries associated with the film quietly distanced themselves. Production of Inchon went on longer than expected and thus over budget. The final estimated cost was around $50 million. It made less than $2 million at the box office, was pulled almost immediately, and never released on home video.

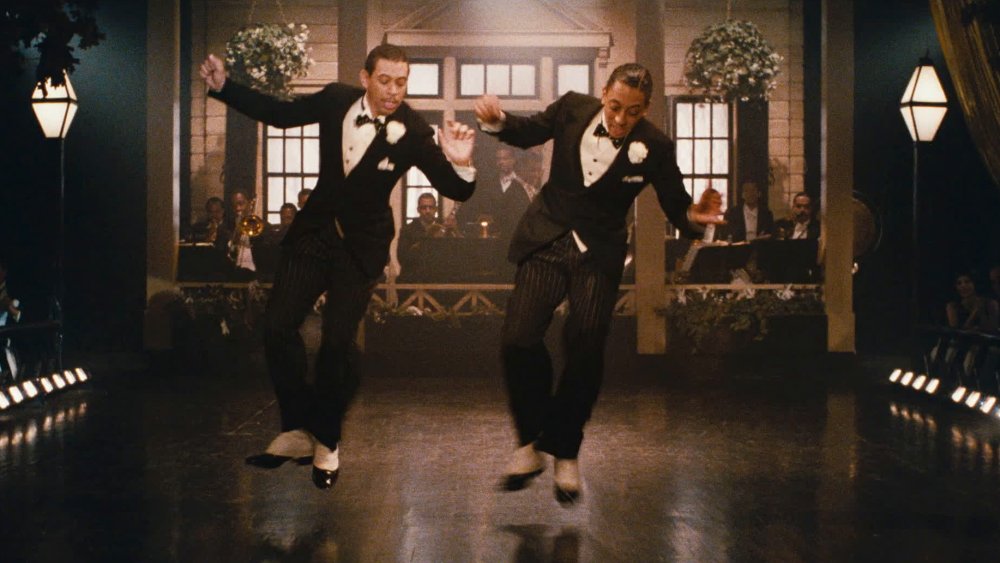

The Cotton Club had a lot of strange funding ... plus a murder

The Cotton Club is often listed as one of Francis Ford Coppola's failures, which is both fair and unfair. It's unfair in that the movie got better critical notices than most remember and picked up some Oscar and Golden Globe nominations. It's fair in that the movie was a huge box office bomb, and the production was troubled beyond belief, including lots of shady funding.

Much of the financing was arranged through producer Robert Evans, who was fresh off a guilty plea for cocaine trafficking. The movie had plenty of strange characters funding it, including Saudi arms dealer Adnan Khashoggi, who both put in and pulled out money.

The most infamous part of The Cotton Club production is the tale of showbusiness promoter Roy Radin. He and Evans, who were introduced by mutual friend and drug dealer Karen Greenberger, agreed to start a production company with the specific goal of making a movie about New York's Cotton Club. Radin offered Greenberger a $50,000 finders fee, but she deemed this inefficient and felt like she was getting cut out of a producer role. As such, she arranged to have Radin kidnapped and murdered. Greenberger and three co-conspirators were caught and convicted.

Between when Radin disappeared and his body was discovered, Evans got a sense of what happened and figured he'd be next on Greenberger's list. According to the book Bad Company, the definitive resource on the Cotton Club murder, Evans took action to get funding and protect himself in the process. He reached out to the Doumani brothers, Las Vegas club owners, for both financing and possibly protection, to which they eventually agreed.

John Cassavetes accidentally invented crowdfunding

Shadows, the 1959 directorial debut of John Cassevetes, is a landmark of American independent cinema. An avant-garde film that was largely improvisational, it set a new standard for low-budget cinema and won critical acclaim. It was also one of the earliest examples of a crowdfunded movie. Years before Kickstarter or GoFundMe, Cassevetes got funding for his movie just by asking normal people to kick a few bucks his way.

In February 1957, Cassavetes (per his interviews with film scholar Ray Carney) went on Jean Shepherd's Night People radio show. He was there to promote a film he starred in called Edge of the City, but he started talking about his vision of cinema. He worried about the state of the business, run by "Hollywood big-wigs who are only interested in business and how much the picture was going to gross." He wanted cinema for ordinary people, opining, "If there can be off-Broadway plays, why can't there be off-Broadway movies?"

Shep asked Cassavetes how he'd raise money for it, to which he responded that regular people should help fund it. Over the next few weeks, over $2,000 worth of small donations were sent to the radio station. This was the start of what would ultimately end up costing (per Criterion) $40,000. Sure, it was still a small sum for a feature-length movie, but it was the start of what he wanted — a movie for the people, by the people, all thanks to strangers sending small bills.

Two movies were funded by mishandled Vatican funds

Peter's Pence is the name of funds sent to the Pope each year by Catholics, ostensibly for philanthropic purposes. The actual implementation of them is another story, as an internal audit around late 2019 revealed massive mismanagement of funds. The Wall Street Journal reported only around 10% of Peter's Pence was used for charitable purposes, with the rest used to plug administrative holes in the Vatican or in sketchy investments. One such investment was in two unlikely movies.

A big chunk of Peter's Pence was put in the Malta-based Centurion Global Fund. How much? Several sources indicated that the Centurion is worth €70 million (around $83 million American), and two-thirds of that came from the Vatican. Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera's investigation into Centurion's investments turned up, among other things, two Hollywood movies – Men in Black: International and Rocketman. The former is something of a curiosity, but the latter caused a big stir in the Catholic press, given the church's vocal opposition to LGBT+ causes. That's right. The Vatican indirectly invested in the first major studio movie to feature a gay sex scene.

Kevin Smith funded Clerks with maxed-out credit cards and comics

Clerks remains both Kevin Smith's most famous movie and the model for low-budget filmmaking. Smith making a blockbuster success on a shoestring budget with a bunch of his buddies is a huge outlier, but it's a source of inspiration. What shouldn't be a source of inspiration, though, is the sheer number of ridiculous ways Smith got the funds for it.

Most of the money came from maxing out credit cards. Smith tried to see how many he could acquire years before making Clerks, and as such, he had at least ten in a box somewhere. There were other strange sources of funding. For example, Smith sold almost all of his massive comic collection, cashed a check from FEMA he got for storm-related property damage, and used his own funds from his day job. He did run into one thing (via Vice) he couldn't charge – the camera, which cost $3,000. His parents took out all of their savings to cover it, with his father saying that he'd have to put his retirement off for a decade if he didn't get his money back.

All of this adds up to a budget of $27,575. The movie brought in over $3 million. That said, production company View Askew slaps a strong "do not try this at home" label for this method on their website, saying, "We don't really recommend this method of funding a film as if your film does not pan out, you will be put in serious financial debt for much of your life." That said, they do recommend making your dream project. Just be more responsible, and make sure your script is good.

A classic adult film and The Texas Chain Saw Massacre were funded by the mob

Deep Throat and the original Texas Chain Saw Massacre have a few things in common on the surface level alone. Both were low-budget exploitation films that outraged audiences while making bank along the way. They've also got plenty in common behind the scenes, as both were funded at various points by a single family of mobsters. This will take a little explaining.

We start in 1972 with legendary porn flick Deep Throat. The film was produced by Louis Peraino, and it was funded by his father, Anthony, and distributed via their company, Bryanston Pictures. The Perainos were connected to the Colombo crime family, and according to the FBI, they strong-armed the rights to Deep Throat from director Gerard Damiano. They got revenue through a process known as "four-walling," where a company rents out a movie theater to collect all revenue as if it were a private screening. Normally, this is only done at one or two locations ... but the Perainos did it at theaters across the country, collecting all of the box office revenue for a movie that was — technically speaking — never released theatrically.

Then in 1974, some of the Perainos, including Louis and his brother Joe at Bryanston, used the money they got from Deep Throat to branch into semi-legitimate business. Around this time, Tobe Hooper had just completed The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and was desperately looking for a distributor. So, Bryanston and Hooper signed a deal. They'd pay Hooper $225,000 for distribution and get 35% percent of the box office. The movie didn't make a profit at the time, due to a combination of fund mismanagement and mob-adjacent shenanigans, but it's gone on to become a horror classic thanks to mobsters and porn money.