The Best Character Endings On The Wire, Ranked

David Simon's and Ed Burns' The Wire may not have won many major awards or enjoyed much ratings success throughout its 2002-2008 run, but its reputation has grown steadily over time. Today, it's widely recognized as one of the greatest shows in the history of television, due to its literary approach to storytelling and its hauntingly authentic depiction of a Baltimore so weakened by crime, rot, economic despair and corruption that it lacks the strength to confront any of them. This produces an endless, self-perpetuating cycle in which small acts of corruption and selfishness contribute to societal breakdown, incentivizing yet more corruption and selfishness, ad nauseam. Some characters figure out how to game the system to get ahead. Others are crushed by the wheel. Always, the poor suffer the most.

The Wire has something important to say, and avoids any clichés or tropes that would've undermined the message. Not all cops are good, not all gangsters are bad. In fact, few characters fit neatly into either box. Every major character had an ending that upheld the themes of the show, and we've ranked them here. (Warning: SPOILERS AHEAD).

Bill Rawls & Stan Valchek

If ever there were two Wire characters who understood how the system really operates behind closed doors, they were Bill Rawls and Stan Valchek, two high-ranking Baltimore city police officers who had no problem playing the politics game to get ahead.

Rawls, originally the head of the homicide division, is first introduced as an antagonist to the perpetually insubordinate Jimmy McNulty, one of his detectives whose nosiness damages the department's clearance rate and forces him to open an investigation into local drug lord Avon Barksdale, much to his chagrin. Stan Valchek, on the other hand, plays a larger role in the second season, when a personal grievance against longshoreman union chief Frank Sobatoka, over a stained glass window in a local church, leads to his calling for a special task force to investigate the man.

Ultimately, neither man had much patience for good police work if and when it stepped on their respective toes. But both were perfectly willing to slit throats to advance their own careers. In the end, Valchek replaces Daniels (who barely served) as city police commissioner, and Rawls follows Carcetti to Annapolis to serve as the chief of state police. It just goes to prove that the system examined in The Wire rewards selfishness and corruption, as opposed to integrity. If anyone won the game, it was these two crooked slimeballs.

Jimmy McNulty and Lester Freamon

Jimmy McNulty, the insubordinate drunk, and Lester Freamon, the old, crafty code cracker, were two talented detectives who hated politics interfering with good police work. McNulty was talented but rash, and had few friends that outranked him. He was constantly being shifted around between whatever departments would have him. Meanwhile, Lester had spent 13 years and four months managing the evidence locker because he asked too many provocative questions.

When the police were forced to operate on a shoestring budget due to Mayor Carcetti's bailing out of a bankrupt school system, McNulty and Lester joined forces to perpetrate the ultimate scam. If they could manipulate murders to look like a serial killer was on the loose, they could force City Hall to refund the police, and use that money to hunt rising drug lord Marlo Stanfield. The scheme eventually unwound (although not before Stanfield and his lieutenants were charged), and the two were pressured to resign. They barely escaped worse consequences, purely because their firing or arrest would embarrass the mayor in an election year.

They weren't the only cops unhappy with the status quo. Jimmy's on-again, off-again partner, Bunk Moreland, also valued honest detective work over playing games and juking stats. But he was able to work better within the system. Then there was Kima Greggs, who by the end of the show had effectively replaced the retired Jimmy as the department's resident insubordinate time bomb.

Roland Pryzbylewski

"Prez" was never meant to be a cop. Before we meet him, he'd shot up his own car and filed a false report. One of the first things he does onscreen is discharge his firearm by mistake, and he later blinds a kid by clocking him in the face with his service weapon. His relation to Major Stan Valchek (his father-in-law) prevents him from being fired, but not from being stuffed away in the back office where his dangerous incompetence can't hurt anybody else.

Surprisingly, he proves to be a remarkably talented code cracker during this soft suspension. He may have been dumped on Cedric Daniels' various task forces because the departments he'd worked in had little use for him, but those task forces came to rely on and respect him. Unfortunately, his rash nature comes to the fore yet again when he punches his father-in-law for an insult. Later, his career in law enforcement ends, instantly and tragically, when he kills another officer by mistake.

It should've been the end for Prez, but he finds a new calling in public education. He initially struggles to reach and control his problematic inner city students. But he eventually becomes something of a rock for these kids, whose lives have been defined by neglect and abuse. But this show was never about happy endings. One of the last lessons Prez learns is one of the harshest: you can't save them all.

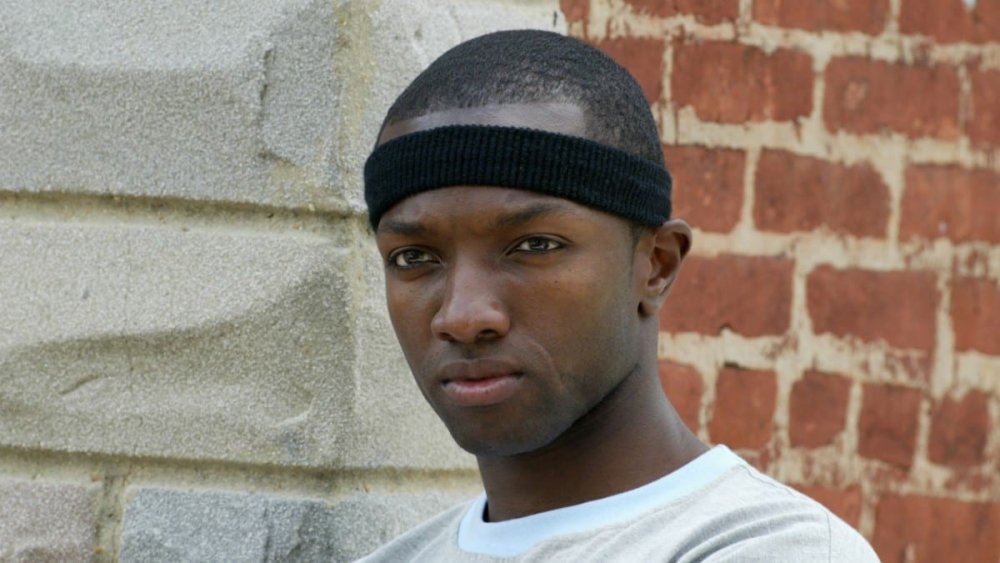

Michael Lee

When Marlo Stanfield tried to buy his and his friends' loyalty by giving them money for school clothes, only Michael turned him down. And yet Michael is the only one in the group who eventually joins Marlo's crew. Turns out the way to his heart isn't to buy him off, but to protect him and his little brother Bug, of whom he is fiercely protective, from his sexually abusive stepfather. Chris Partlow, Marlo's most trusted lieutenant, kills the man so violently it's likely he was abused himself as a child.

After this, he and Snoop, his equally violent partner, take Michael under their wing. For a time, it looks like the kid will eventually become one of them, but this isn't the case. Michael was always smarter and more inquisitive than the average corner boy or soldier. It was a trait that made him both promising and potentially problematic. When the cops finally make a move on Marlo and his boys, Michael is suspected as a snitch, and Snoop is tasked with killing him. He beats her to the punch.

Now cut loose from the collapsed Stanfield Organization, Michael takes care of those who depend on him. He then briefly goes into hiding before re-emerging to rob drug dealers with a shotgun, thus taking up the mantle of stickup man recently vacated by the late Omar Little. It might've been hard to see coming during your first watch, but in hindsight, Michael's independent streak could hardly have produced a different outcome.

Bubbles

Few characters get happy endings during The Wire. Most are fired, killed, imprisoned, replaced, or otherwise left to fend for themselves in a system that's unforgiving and vicious. And nobody seems more destined for death and despair than Reginald "Bubbles" Cousins, a heroin addict and police informant. By season five he's been constantly neglected by the police he often helped, repeatedly rejected by his family that he'd hurt one too many times, brutally beaten, and is reeling from the loss of several friends to the opioid devil.

So it's surprising, after years of watching him try and fail to bootstrap himself out of addiction, to see him actually pull it off. Bubbs ultimately learns he can't rely on others to save him; he has to succeed where his friends failed and find the strength to survive within himself. And he does, despite years of setbacks and false starts. His journey remains quite possibly the most haunting, tragic, and authentic depiction of addiction in the history of television, and it ends triumphantly with Bubbs, rejected no more, joining his sister's family for dinner.

Sadly, his role as an addict isn't left unfilled when he cleans up. "Dukie" Weems, a local student, ultimately takes his place as the junkie. When the endless wheel of rot and despair examined by The Wire is nice enough to eject someone into a happy ending, it makes sure to exact payment from whichever poor soul fills the vacancy.

Bodie Broadus

Bodie Broadus, a low level Barksdale corner boy when we meet him, certainly doesn't seem promising. But The Wire is a master class in subverting expectations. Not in the obnoxious, gimmicky way you associate with that phrase, but by taking characters who would've been treated as one-dimensional in lesser shows and making them fully human.

Bodie is made of far tougher mettle than many other kids and corner boys he works alongside. The cops can't break him; he takes their beatings on the regular, never loses that smirk, and even earns their begrudging respect. Even Marlo Stanfield doesn't scare him. After the Barksdale organization collapses, Bodie is one of its last remaining loyal holdouts, resisting absorption into Marlo's crew until he has no other choice.

But Bodie can never bring himself to be truly loyal to Marlo, even after he starts working for him. The Barksdale organization was ruthless, sure, but there were rules and norms there that Bodie felt legitimized that behavior. He sees no reverence for those structures in Marlo; only sociopathic cruelty. His unwillingness to sign off on that is ultimately his undoing. He ultimately confides in an enemy of his enemy, detective McNulty, who's hunting Stanfield. He makes a doomed last stand when Chris and Snoop inevitably come to kill him for snitching.

Viewers might correctly see his death as tragic and avoidable. But to him, no other ending was acceptable for a soldier.

Tommy Carcetti

When we're first introduced to Councilman Carcetti, ripping then-police Commissioner Burrell a new one at City Council over the felony rate, it's natural to assume he's just another cutthroat politician who only pretends to care. After all, learning more about the characters of The Wire rarely makes us like them more, even if further examination does humanize them. But Tommy surprises us, pleasantly, over the course of the series. He's no saint — he has an infidelity problem, for starters — but he does genuinely care about cleaning up an ailing, broken city.

When he becomes Mayor, he starts off on a good foot, genuinely trying to get things moving in the right direction. But then reality sets in. The schools are in severe debt. The Republican governor is no help, and if Carcetti wants that job eventually (he does indeed), he can only embarrass himself so much asking for assistance. The police are then left hanging out to dry due to their funding being stripped for the schools, and yet crime remains a top political issue in Baltimore.

At this point, sadly, Carcetti does indeed become who we thought he originally was. Backed up against a wall politically, he begins tolerating, and then demanding, that the police "juke the stats," meaning massage them to make the crime rate seem more palatable than it is. It's this betrayal of his own ethics that forces out Commissioner Daniels after only days on the job.

Marlo Stanfield

Marlo had no respect for the institutions of the drug game nor any of its players. He was powerful, sociopathic, and willing to dismiss norms and shed amounts of blood that shocked even the veteran gangbangers who'd survived his ascent. The Barksdale organization collapsed trying to stop him. The New Day Co-Op, an attempt by the city's many gangbangers and drug lords to peacefully coexist in the interest of profit maximization, couldn't contain him. Even Omar tried and failed to take him down, and then the police case against him hit a wall due to the misuse of wiretaps, allowing him to walk free (with the caveat that he retire from crime or face harsher consequences).

On paper, it seemed as if Marlo had won the game. But this wasn't the case, as Stanfield was never after freedom, or even money. Like Avon Barksdale before him, and unlike rivals Stringer Bell and "Prop Joe" Stewart, Marlo sought the "crown" of wielding the most feared name on the streets. He succeeded, but only temporarily; his name faded with his short-lived empire. He realized this after a street fight in which his opponents neither knew nor cared who he was. To make matters worse, the name of his supposedly vanquished arch-enemy, Omar Little, still rang out on the streets with reverence and awe. To Marlo, this was a fate worse than death or prison.

Omar Little

Omar's death is undoubtedly one of the most abrupt and unexpected moments of the show. He's shot dead so fast you might've had to rewind to make sure that it had actually just happened. Yep, it did. Omar Little, the stick-up man who struck fear into the hearts of even the hardest criminals in Baltimore, and made robbing them look easy, was indeed taken out by a little kid, in a dumpy corner store, while buying cereal. What?

On a lesser show, it would be infuriating to see such an iconic character flushed down like this. But The Wire earned the right, and the more you examine it, the more appropriate you realize it is.

Omar usually strolled around with body armor and a shotgun, but his name and reputation were so powerful he hardly needed either. Dealers he hadn't even known were there would often toss their stash at him when he went outside, unarmed and in his bathrobe, to run errands. Nobody who knew him wanted to be on his bad side.

So naturally, he isn't taken out by any of the ruthless kingpins he loved to antagonize, but by a kid too young to truly understand who he is. Youth disrespecting and upending the establishment is a common theme in The Wire, and not even Omar himself, to whom the rules rarely applied, is ultimately able to escape it. It's all in the game, yo.

Cedric Daniels

How does a noble man make heads or tails of a world that only pretends to be noble? Cedric Daniels is a career man with an eye on advancing through the ranks of the Baltimore City Police Department. However, his integrity handicaps him: good police work can only get you so far in a system that rewards political gamesmanship and cutthroat ambition above all else.

The rise of Mayor Tommy Carcetti, who also shunned corrupt institutions and sought to restore some integrity to the government, opens the door at last to Cedric's long-deserved promotion to Commissioner. But despite the Mayor's sincere promises to turn a new leaf and never put his subordinates in an unethical position, politics soon get in the way, as they're wont to do, and Commissioner Daniels finds himself on the receiving end of exactly the type of requests he was promised he wouldn't receive: those to juke the stats (manipulate numbers to make crime rates look less severe) to keep the mayor's head above political water. He's promised these are only temporary, election year measures, but Cedric has been around long enough to know that once you start excusing unacceptable behavior, you don't stop. Ultimately, unable to make the moral compromises his position demanded, he resigns in favor of a career as an attorney. Stan Valchek, whose cackling, gleeful corruption made him a much better fit to lead the police, replaces him at the head of the table.

Stringer Bell

"When I look at you, I see a man without a country. You ain't hard enough for this right here. And maybe, just maybe, you ain't smart enough for them out there."

Avon Barksdale, Stringer Bell's less educated but wiser partner, is correct in this assessment. Stringer long sought to legitimize both himself and the drug empire he helped run with the aesthetics and language of business, but this is a mirage. He wasn't above using force to resolve disputes when dialogue and compromise failed to produce a more respectable version of a drug game that was inherently violent and grotesque.

Stringer understands the streets, but not the world outside and above them, where criminal conspiracies are hatched over three martini lunches, not street corners. His misguided ambition ultimately brings him into contact with four people he can't control: Clay Davis, a corrupt state senator who promises to open all the doors of the corporate underworld to Stringer only to rob him blind; Marlo Stanfield, the newcomer with no respect for the "rules" of the drug game or any of its established players; Brother Mouzone, a hit man that doesn't take kindly to the hit Stringer put out on him; and Omar Little, the stickup man whose boyfriend he savagely murders. But it's Avon himself who set Stringer up to be taken down by the latter two, after realizing his old friend's grandiose delusions have imperiled everything they'd built.