Must-See Fantasy Movies For People Who Hate Fantasy

Fantasy isn't for everyone. Suspension of disbelief itself is a pretty big demand to place on an audience, and if a film cannot convince the viewer to entertain the impossible, the entire effect is lost. Like their sister genre, sci-fi, fantasies are something of an experiment, in which the laboratory is our own minds. They lay down a specific set of parameters, like laboratory conditions, creating a path of least resistance for the answers to "what if?" And like many scientific studies, these endeavors rely on internal validity: They do not promise replicability outside the confines of their own universe. They only show you what's possible under a specific set of assumptions.

But one concern about making such assumptions is that they eventually reach a height that sacrifices the plot, for example through the idea of deus ex machina, or in this case deus ex magicae, that there is a trump card inherent in fantasy: Theoretically, one entity could be so unrealistically powerful as to achieve victory as if there was never any real danger. The constraints of reality create a struggle for survival, that struggle creates conflict, and that conflict drives plot. This is a big reason it can be hard for many to "get into" fantasy, among others such as disapproving of escapism or preferring storylines that could actually happen in the present or future, a story you can actually approximate to your own life. If these are your objections, then the following may be the stories for you.

The Science of Sleep

Many people find themselves averse to fantasy because they may have a narrower view of what the genre actually is. Sometimes, the most fantastical world is only about 140 millimeters wide: the one inside someone's head.

The Science of Sleep is bemusing, to say the least, one of the most innocent-but-perturbing, whimsical, and tragic movies out there. The 2006 film blurs the line between reality and imagination in a sensitive, meandering love story, which begins when the main character, a demure man named Stéphane, moves to Paris from Mexico to be with his newly widowed mother. He meets Stéphanie, who lives in the apartment next to him, and initially forms an attraction to her roommate, Zoé, while suspecting anyway that it is Stéphanie who is interested in him. Over time, he begins to realize his greater compatibility with the latter, but his vivid imaginary and dream life interferes with his ability to perform socially (and in general), leaving him, and the audience, confused as to which is which.

This sense of fantasy, rather than making the conflicts too grand and unbelievable, simply exacerbates the tension that inherently exists in each character's personality. Like the little inventions Stéphane builds (including the One-Second Time Machine), the elements of fantasy are tools of his own creation as well, highlighting his neuroses and lending a ginger genuineness to the way the main characters hurt and heal each other.

Zathura

Can't get into undead dragons like on Game of Thrones? There's no definite opposite to that level of unreality, but a children's board game is a pretty far cry, to say the least, seemingly about as mundane a premise as they come. But the commonplace ends there in 2005's Zathura.

The space adventure is dramatic and a little morbid, with the undercurrent of tense family dynamics taken to the extreme under the warped conditions of the magical board game. Walter, his younger brother Danny, and his older sister Lisa are an antagonistic set of siblings left home alone to entertain themselves when their divorced father leaves for business. The dusty board game they find in the basement leaps right past being entertaining and into the realm of downright terrifying. Young boys may hate their sisters, but they'll probably stop short of wanting to see them frozen to death.

Using children as protagonists can help put us in a susceptible frame of mind, while it remains nostalgic for older adults who have childhood board games stashed in their attics. The movie doesn't get too epic in scope: Yes, there may be holes ripped in the fabric of time and space, but the entire movie essentially takes place inside in a suburban home.

Princess Mononoke

Princess Mononoke, from 1997, is not only incredibly beautiful in terms of aesthetics, but it explores deep themes with a splash of gore, resulting in something a little more intense than typical folklore or fantasy. For those worried about the god in the machine threatening the integrity of the story, this cinematic machine offers a demon instead.

While the film absolutely does explore the well-trodden ground of the good-vs.-evil formula, it does so in a subtle and moving way. When the last Emishi prince protects the village from a demon boar attack and is corrupted himself through his wounds, he seeks the help of the Great Forest Spirit. Along the way, he encounters a human girl who was raised by wolves and who exposes him to the corruption of Irontown, which was built by clear-cutting forests to produce iron from ironsand. It was an iron bullet made by the firearm manufacturers of this town that wounded and corrupted the boar god from the beginning of the tale.

But even though the people and leadership of Irontown cause so much chaos, they are themselves the victims of oppression and alienation by others: Lady Eboshi created the town as a haven for social outcasts, like lepers. Thus, the film explores the tenuous space between the interests of vulnerable areas of society. In this way, at the very least, Princess Mononoke is much more relevant to "real" life than we typically give fantasy credit for.

Doctor Strange

Superhero movies can often be said to fall under their own generic umbrella and can alienate audiences for a similar laundry list of reasons to fantasy or even err closer to the side of science fiction. (Marvel's Iron Man is a prime example from 2008.) But 2016's Doctor Strange uses enchantment and magic to tell the story of a rough-around-the-edges character who brings realism, if not to our conception of the universe, to our idea of a hero.

This hero is an arrogant surgeon who suffers a hubristic accident that leaves him with no hope of returning to his former life. He searches for an easy way out, a miraculous cure found in some expensive experimental procedure. What he is searching for is a fantasy, is escapism: What he finds is magic, but it is the opposite of an escape. Nothing could more powerfully force him to confront the reality of his own arrogance, and on top of that, he sort of becomes responsible for the fate of the world(s). If you don't like traditional fantasy, the superhero-style action, predicated on the survival of the real world, may be up your alley.

Maleficent

The good-vs.-evil paradigm might seem a bit predictable by now, but the evil-vs.-good premise still has some mileage left on it. This 2014 film, Maleficent, is about the villain, not the whimsical princess heroine. The most impressive piece of magic in this movie, though, is that it separates the villain from the villainous: Yes, Maleficent is guilty of vengefulness and destruction as in the classic fairy tale, but these issues arise from a protective nature, fear, and a broken heart.

Maleficent was the protector of the Moors and had her wings severed in an invasion, causing her to turn the land into an evil kingdom and swear vengeance (the familiar finger-prick curse of eternal sleep) on the daughter of the man who took her wings. As she surveils Aurora in anticipation of her 16th birthday, when the curse will be realized, she begins to care for her maternally and attempts to undo what she has done.

In a way, the evil queen is actually the hero, taking on the mammoth task of protecting someone else against herself – and in the process, letting go of the resentment of the past in order to open the future to true love. This kind of personal growth is something we'd all like to believe is real.

Pan's Labyrinth

The 2006 dark fantasy Pan's Labyrinth, by Oscar-winning director Guillermo del Toro, takes place in a magical-realist timeline after the Spanish Civil War, where the lives of characters from an old fairy tale are intertwined with those of humans. In the fairy tale, the daughter of the king of the underworld visits the surface, becomes mortal, and dies: In postwar Spain, a ten-year-old girl named Ofelia is believed by various magical creatures to be the reincarnation of the king's daughter, Moanna, while in her real life, her mother marries a ruthless captain assigned to hunt down the republican rebels left over from the Spanish Civil War.

Pan's Labyrinth deals with immortal underworld rulers and cosmic tests but remains tethered to the real world by the bonds of family and the seriousness of a country torn apart by war. Ofelia must confront death and danger at every turn, both as she fights to reclaim her immortality as Moanna and as she fights to preserve her family and navigate the violent influences close to her in the midst of war. The fantastical concept of eternal life is the film's way of expressing the responsibility of each generation to navigate their mazes and battles and leave the world more moral for those who will tread the path next.

Dogma

Kevin Smith's irreverent 1999 comedy Dogma is about fallen angels, human prophets, and indulgences. These things aren't just the stuff of religion, legend, or history in this film: Smith brings to life the classic elements of religious tradition in a satirical, no-holds-barred way.

The fallen angels in question, Bartleby and Loki, are trying to make it back into heaven, but Bethany, a counselor at an abortion clinic and the last, distant living relative of Jesus Christ, learns that if the two are allowed to re-enter the pearly gates, it will throw God's omnipotence into question and threaten all of existence.

Though it has elements of both, this film is not simply a fantasy movie or a religious movie. It is informed enough to be clever and offer creative takes on classic ideas of religion, such as the angels' resentment that humans were gifted with free will while angels were forced into servitude. No matter what your background, you can appreciate something about this film, from the satire to the creativity.

The Princess Bride

The Princess Bride rests on the very human struggles of love, loss, and revenge. The specter of mortality is never absent, and some of the most impressive feats are, if not realistic, at least conceivable on the upper end of human physical limitation, without a magical intervention. Take, for example, the poison immunity of Westley, bestowed upon him not by supernatural providence but by his own calculated inoculation: He has been poisoning himself for years so that, with his tolerance, he can best another man in a game of wits involving poisoned cups.

The fantastic elements of this 1987 film are nearer to the realm of the possible than in many other examples of the genre. Princess Buttercup fights to reunite with her once-thought-dead love and avoid a partnership with a warmongering prince who has her worst interests at heart. Along the way, there are giants, folk healers, pirates (which often show up in fantasy but also exist in real life), and Rodents Of Unusual Size, but that's about it: The rest of the story rests upon conspiracy, romance, desperation, and even torture. There are elements of Romeo and Juliet and typical damsel-in-distress narratives, all with an oddball, incredibly quotable twist.

Birdman

One of the most supernaturally gifted "characters" in 2014's Birdman is the camera. The film is presented as a single shot, set in a theater, and designed more as a comedy than the habitual drama and tragedy of award-winning director Alejandro G. Iñárritu (like his previous film, Biutiful, from 2010). The single-shot appearance of the production mirrors the nonstop stream-of-consciousness mockery and torment visited upon the main character, Riggan Thomson, by his former superhero alter ego, Birdman.

This is another film that blurs the line between identity, imagination, and reality while also exploring the intricacies of a mid-life crisis through its unique filming style. Ambiguity, then, is also a fantasy hero in this instance, mystically allowing each member of the audience to take something different from the film's climax. With all this talk of genre, the Birdman himself deplores labels. One reviewer uses this hatred of labels to call on the nature of Riggan's powers: No matter their degree of realism, they offer us, and him, the freedom to move beyond labels and expand our personal realm of the possible.

Fantastic Mr. Fox

Like the rotoscoping techniques of Richard Linklater's Waking Life, the animation style of 2009's Fantastic Mr. Fox also lends an air of imagination and surrealism to what would already be quite a curious production. The detail alone is incredible to watch, like an intricate diorama, and the wry Wes Anderson humor will draw in fans and film buffs to these sapient foxes and their lives of thievery and family ties.

Instead of incorporating talking animals into the human worldview, the creators of this film have incorporated human elements into the fantasy world: foxes who dress, walk on two legs, and talk. Of course, there are humans in the world of Fantastic Mr. Fox: They are the chief antagonists. But part of what makes them antagonists is how blissfully unaware they are of the rich mental, emotional, and social lives of the "pests" they so shamelessly attempt to entrap. Instead of a lofty, head-in-the-clouds fantasy, Fantastic Mr. Fox is a grounding adventure. (Because they live in burrows in the ground.)

Waking Life

An uncommon response to the qualms about fantasy's removal from anything that could actually happen to a human being, even in the distant future, is Richard Linklater's 2001 experimental film Waking Life. This film, according to many interpretations, shows us not something that couldn't happen, not something that might happen, but something that will happen to every single person: We will die. What the film leaves to fantasy is speculation about what that will look like.

Linklater didn't make the film until long after he had the idea because releasing it in live action would have been "too realistic." He needed to make an unreality based in the real world. In its final form, this unreality follows a protagonist through a series of seemingly unrelated interactions. These conversations center around themes of reality, lucid dreaming, identity, the collective unconscious...

And slowly the protagonist realizes, through a series of tests like flicking the light switch (if it's unresponsive, that's a bad sign), that he is not living in the real world. At first, he is unnerved, thinking he is stuck in a dream and can only wake into another dream. Then the conversations take a turn. We start getting implications, and at one point, he himself muses aloud that he might actually be dead or in the final moments of his life, a time in which we don't really know what the mind does. Perhaps it creates a fantasy.

Bridge to Terabithia

Is it fantasy, or is 2007's Bridge to Terabithia all in the children's imagination? Those who grew up on the film or the 1977 novel it was based on know that Terabithia is real — if nothing else, its story possesses the very real ability to make us cry every time. And what brings us to tears is not a magical triumph or defeat. It is the brutal reawakening to the real world and the struggle to preserve and pass on the magic that outlives those who first illuminated it for us.

The story of Jess and his blooming friendship with new neighbor and fellow 12-year-old Leslie, who helps him build a treehouse fortress and shows him how to make imagined worlds real, is not just a fantasy itself but a study in the tradition of fantasy. Leslie's unbridled imagination whisks Jess along, and when she dies tragically, he uses fantasy to celebrate her life. But just as importantly, he shares the world they built together with his younger sister, Terabithia's new princess. This act mirrors the way we pass down the folklore of our various cultures. Our heritages and identities are some of the most real parts of us — and fantasy makes them immortal.

Being John Malkovich

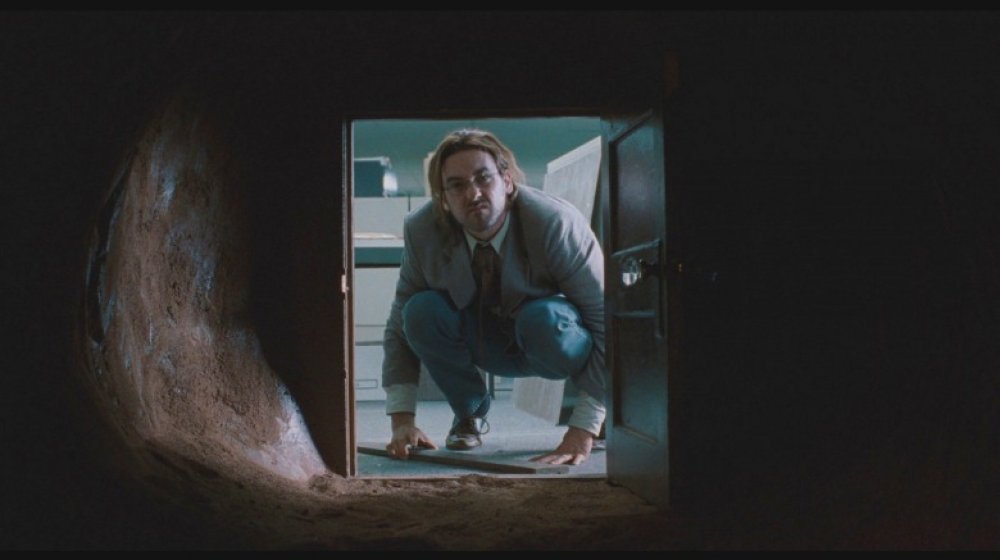

Premiering in 1999, Being John Malkovich was a fantasy comedy that went beyond weird, asking deep, dark questions about humanity, identity, and the universe, at once making you uncomfortable and full of laughter. When a dejected Craig finds work as a clerk on the seventh-and-a-half floor of a building and doesn't seem to question it as much as he should, the audience knows they should buckle in for a ride.

Craig's ride begins when he finds a small door in one of the filing rooms. Upon entering, he is sucked through a moist, unappetizing tube and lands, by all appearances, in the mind and body of actor John Malkovich. He becomes increasingly able to control the body because of his skills with puppeteering. After this, we watch many other characters take on the adventure of "being John Malkovich," including Craig's wife, Lotte, who awakens her transgender identity through the experience. The story escalates from there, through themes of cultism, eternal life, and hive minds. It's safe to say that the film doesn't play out like a typical fantasy. It originates in an office building, like many of our mundane days, but it's easy to forget that by the end.