Things Only Adults Notice In X-Men: The Animated Series

With its serious, long-running story arcs, X-Men: the Animated Series was different from almost every other cartoon of its day. It helped to reinvigorate Saturday morning cartoons, as well as pave the way for Mighty Morphin' Power Rangers and the X-Men films. What made this version of the X-Men stand out? Chiefly, its powerful mutants, whose depth stands out to this day. Our mutant heroes lend themselves well to interpersonal stories, tales of bigotry, and even political sagas. The show's storylines are dense, continuously building from previous episodes — and in many cases, pulled straight from the pages of classic X-Men comics. This level of storytelling endeared the show to the previously established fan base, and also got younger viewers interested.

Being a Saturday morning cartoon, building up a franchise that was new to television, and being entertaining to older audiences is a balancing act. The show's staff fought against producers trying to demolish their budgets, ridiculous merchandising integration, as well as the trouble of having its writers in California, voice talent in Canada, and animators in South Korea. But the series managed to work through all of these things while treating its audience, no matter what age, as intelligent and eager. We're here to explore those details aimed straight at the older X-Men audience the series fought so hard (and successfully) to establish and entertain.

A show for the unsung

Disenfranchised people have long seen themselves in the X-Men — and the animated series knows it. According to writer Julia Lewald, Fox was "very conscious of making the show inclusive without being intrusive about it." This resulted in the introduction of Bishop, one of the more memorable guest characters in the show. Racism is also handled head-on, as when someone is upset seeing Storm and Wolverine hold hands. The series also doesn't shy away from powerful women, allowing Rogue, Storm, Jean Grey, and others to dazzle on screen. This was accomplished in part by deliberately hiring more female writers. Though producer Eric Lewald has noted that toys of the female characters may not have sold as well as their male counterparts, no toys were selling well back then, and so the team was free to write the X-women as true heroes.

X-Men is even progressive where gender identity is concerned. Consider the actions of shapeshifters such as Morph and Mystique, who often change gender to flirt with others. As there are several articles and podcasts discussing this subtext, it appears to have stuck.

Mutant politics

It might seem smart to keep politics out of a Saturday morning cartoon, but there is no way to completely eliminate the political nature of the X-Men. One of the series' main antagonists in the first few episodes is Senator Robert Kelly, who declares his intentions to run for president. Kelly is playing to his base, which means that his policies are heavily anti-mutant. Later on, Professor X takes center stage when he meets with politicians, and even goes to Washington, to speak on the behalf of mutants everywhere. Russian politics come up in an episode in which Colossus' past is explored and Omega Red attempts to overthrow the government. Not even the Canadian government looks clean, once Wolverine's past is covered in a searing episode.

X-Men also explores intra-mutant politics, like those of the Morlocks, a band of mutants who dwell underground. Storm ultimately challenges Callisto, their leader, in an effort to save the team. Her victory makes Ororo the technical leader of the sewer-dwellers, though she doesn't stick around to abuse that power and later relinquishes it back to Callisto. In the series finale, we further learn about the Mutant Containment Bill. This nods to the "Days of Future Past" episodes, which show a dark timeline where the Mutant Control Law rules over an anti-mutant dystopia.

The birds, the bees, and the mutants

Superhero comics focus on individuals drawn at peak physical condition, who are poured into tight spandex. The X-Men and many of their foes are no exception, and their cartoon gets positively risque at times. Consider Rogue, who is one of the more flirtatious characters in the show — next to Gambit and Wolverine, of course. She deals with the fact that she can't touch anyone by delivering flirty lines: When Rogue first sees Colossus, she muses, "Now that is a shame, locking up a big good looking hunk of mutant like that." Rogue's voice actress, Lenore Zann, has said that creators were looking for a "husky female voice with a Southern accent." Clearly, they got what they asked for.

Flirty interactions between unexpected characters often make the most impact in X-Men. Sabretooth asks Wolverine if he wants to "kiss and make up," while in the same episode, Rogue urges Cyclops to "make a girl feel welcome" before giving him CPR. She assures the team leader that he shouldn't worry, because she won't tell Jean — but follows this up once their powers return to normal by saying, "We'll have to do it again sometime."

Things get really overt when Cyclops is kidnapped by the Morlocks for the purpose of giving Callisto an heir. Another episode sees Morph trick Gambit into kissing Rogue, thus knocking himself out. Kissing, however, is not exactly what Morph-as-Rogue implies they might do.

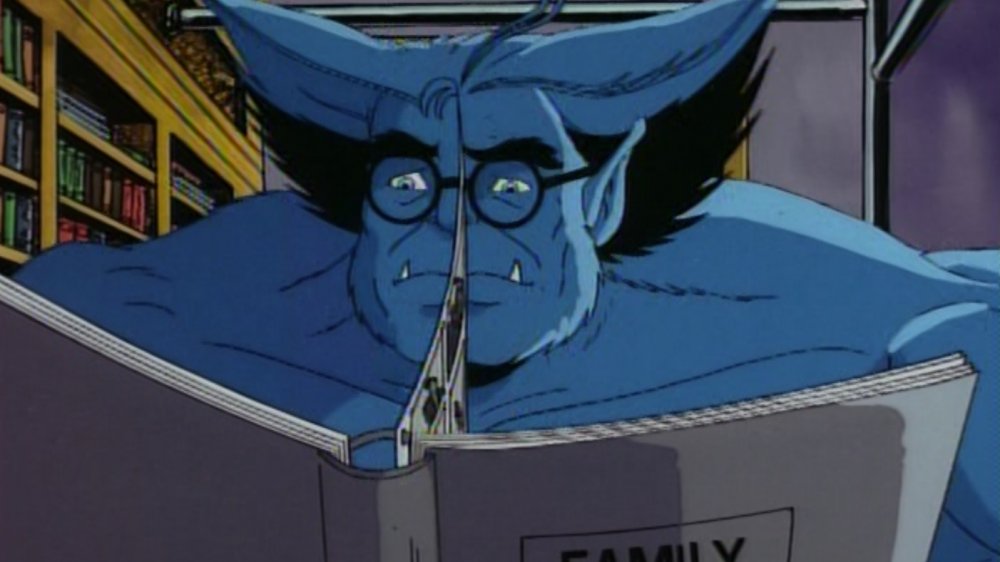

The intellectual Beast

Though the character spends the majority of the first season in jail, Beast is, in fact, lucky to be there, since he was almost not included in the show at all. George Buza's performance and the writers' passion for the character made sure Beast became a bigger part of season two. Audiences see Beast's big brain at work all the time, and are regaled with his many musings, philosophical answers, and overly verbose intellectual statements. Younger viewers are most likely confused by this blue-haired genius, as when, in episode one, he discusses a teammate's "nom de guerre." Adults, however, get a good chuckle out of it. Beast is often seen reading, especially while in prison. It pays off: He readily cites the works of Shakespeare, Lord Tennyson, and John Donne.

Beast isn't the only one who gets to deploy references kids won't grasp, however. Morph gets some stolen Robert Frost lines in. Wolverine quotes Dirty Harry and The Shining to terrifying effect. Rogue makes an obscure golf reference. Then there are the large number of scientific terms used throughout the series, as when the team learns about temporal displacement and Darwinism. No one can accuse X-Men of not being educational!

Slavery, bigotry, and imprisonment

Slavery infests some of the darkest parts of human history, and depicting it, even in a Saturday morning cartoon, can leave quite an impression. In the episode "Slave Island," several members of the X-Men are sent to investigate the tropical vacation spot and mutant utopia known as Genosha — but everything about the island is a lie. The heroes are soon captured and thrown into cells with other mutants, who are being kept alive to be used as slave labor. Each of them is forced to wear a collar that dampens their powers, except when their powers are necessary to do manual labor. It's brutal, but it makes sense that if mutants were real, they would not only be exploited, but enslaved as well.

Other forms of extreme bigotry are explored within the series. Storm and other X-Men help free a group of alien slaves who are controlled by armbands. When exploring Magneto's past, the Holocaust is alluded to. Mutants are rounded up and imprisoned (especially in episodes exploring the future), and Senator Kelly even talks about putting them in internment camps before he is saved by the X-Men and turned into an ally. Mutants always seem one step away from being banished, segregated, or losing all of their rights.

Bigotry has a face

The X-Men deal with hatred and persecution constantly. It's a theme that is explored throughout the majority of their comics, and the cartoon captures it excellently. Mutants are hated, hunted, and attacked. Their most active human enemies are soon given a name: The Friends of Humanity. It isn't hard to see that this collective is meant to mirror modern-day white supremacist groups, down to their symbolism, rallies, and mob-like mentality.

The best example of this comes in "Beauty and the Beast." Beast and a colleague have developed a treatment to restore a young woman's sight, but her father hates Beast and wants him away from his daughter. It's a touching story, as Beast is in love with the young woman, who is later kidnapped by the hate group. It is also one in which children learn the word "bigot," and receive a clear example of what bigotry is. The episode ends with the revelation that the leader of the F.O.H., Graydon Creed, hates mutants because his father and mother are notorious mutant figures Sabretooth and Mystique. Creed takes his hatred to a whole new level when he tries to eradicate his entire mutant family in a later episode, just to get back on the F.O.H.'s good side.

AIDS and the Legacy Virus

The AIDS epidemic was a major part of the '80s and '90s, one which led to the stigmatization of the gay community. As the X-Men are often seen as a reflection of the gay community, among other marginalized groups, it isn't a surprise that an arc about a virus that excels at killing mutants has drawn some comparisons to AIDS. Granted, the Legacy Virus storyline is a bit convoluted, what with its time travel and the whole plague being a plot by the villain Apocalypse. But there are still some poignant moments, and the comparison holds.

The manufactured Legacy Virus is used to falsely frame mutants in a bad light and generate more hatred toward them: Anti-mutant bigots claim mutants infect humans with the sickness. Graydon Creed, leader of the F.O.H., accidentally infects himself with it and blames this on Bishop, who was actually attempting to stop him from injecting the virus into someone else. In the future that Bishop is trying to prevent, many mutants are shown to be locked up in quarantine out of societal fear, and even more have died from the Legacy Virus. It's all part of Apocalypse's evil scheme, concocted in the far future. Though the X-Men do eventually save the day, the image of stigmatized, suffering mutants lingers.

Loss and death

Being a member of the X-Men isn't easy: The fighting is constant, and often leads to death. Kid viewers are exposed to this early on in the first story arc, when Morph is thought to have been killed. Later on, the "Dark Phoenix" storyline deals a devastating blow to the X-Men with Jean Grey's (temporary — but they don't know that) death. There is also the series finale, which sees the team deal with the loss of Charles Xavier, who narrowly avoids death but becomes lost to his mutant family, perhaps forever.

The show also explores several alternate worlds, which force viewers to confront the deaths of beloved characters. The "Days of Future Past" episodes follow Wolverine in the future, condemned to walk past the graves of all his fallen friends. Another world features a married Wolverine and Storm, who are recruited to help set time right again. Tragically, doing this means that their lives, and their love, are erased. The tears they shed when they realize that they have succeeded are deeply sad — though we do get a little flirting between the two back in the correct timeline, to suggest something could still happen. The most unique instance of loss on the show comes when the mansion is destroyed. Wolverine reminisces out loud about how it is one of the few homes he's ever known. Seeing someone so stoic lament a building is a moving moment.

As the mutant world turns

The X-Men have a lot of baggage. Relationship drama is constant: Classic love triangles proliferate, most prominently between Cyclops, Jean Grey, and Wolverine, as well as unrequited love and even divorce. Several mutants are disowned by their parents. The "Proteus" episodes reveal that one of the world's most powerful mutants just wants acceptance from his father. Jealousy flares up, as when Cyclops protects Dazzler, enraging Jean, then possessed by the Phoenix. Throw in several interrupted marriages (remember Storm and Arkon?), surprise announcements of parenthood, as well as a couple of shapeshifters, and things get crazy. Morph pretending to be Scott and Jean's priest to ensure their marriage's illegitimacy is perhaps the peak of this pettiness and drama.

Frankly, X-Men feels like a daytime soap at many points. But these ultra-emotional moments also make the characters feel very human. The series' writers wanted to showcase the characters battling their own inner demons as well as their physical enemies, which ultimately made for good depth of storytelling. Plus, as there isn't a lot of media for kids that discusses things like death, divorce, and how to deal with strong emotions, X-Men is downright helpful to little ones seeking guidance. The show knows kids aren't stupid, even if they don't grasp every single detail the way their parents do. Incorporating so many dramatic elements might make the show soapy, but it also makes it important.

Mutants of faith

Religion is very much a part of X-Men. Fictional religions exist, like those who worship Garokk in the Savage Lands. Moreover, Storm herself is sometimes referred to as a goddess. Christianity is also present on the show, explored in episodes like "Descent," which discusses the evolution of mutants, and episodes featuring Nightcrawler, whose Catholicism is a big part of his character.

Nightcrawler has a demonic and unsettling appearance, with blue skin, yellow eyes, fangs, oddly shaped extremities, pointy ears, and a tail. He even smells like sulfur when using his teleportation powers. It's no surprise, then, that a mob comes to destroy Nightcrawler, insisting that God is with them on their mission. This episode explores having faith, losing it, and renewing one's relationship with the divine, as well as bringing up the question of why God would create mutants in the first place. In an unexpected moment at the end, Nightcrawler gives Wolverine a Bible, with several marked passages. The episode ends on a scene of Wolverine reading passages out loud in a church. This is particularly striking, given Wolverine's cynicism, but Nightcrawler's kindness has reached him. The demon lookalike speaks often about forgiveness and compassion, even for those in his family who did horrible things to him. He always tries to live by God's words — and X-Men is interested in exploring what that means, with a depth only adults truly grasp.

Violence is omnipresent

X-Men is full of violence. But as is the case with many cartoons, few kicks and punches can actually connect, lest things get bloody. The inclusion of Sentinels and other robots as primary antagonists helps tremendously with this dilemma. These giant menaces are a godsend for simulated violence: As Julia Lewald remarked, "If action's going to be big, it's going to involve Sentinels getting bits torn off and thrown about. You couldn't do that with living things." Ripping cybernetic parts off of a human, as happens with Donald Pierce during the fight with the Hellfire Club, is also allowed, but skirts the line. These workarounds allow fans to see Wolverine and others decapitate, dismember, and eviscerate their enemies, using their powers to their fullest extent.

Violence is also present in the sheer amount of fighting the X-Men do with each other. It may be a bit odd to see these supposed teammates constantly at each other's throats, using their powers against one another, but that's the X-Men for you. Many characters also go out of their way to hurt innocents, or are obsessed with being cruel, like Sabretooth. Magneto swears revenge on quite a few people, Cable spends his life trying to destroy one person, and Archangel dedicates his wealth to tracking down and destroying Apocalypse, in an episode blatantly titled "Obsession." Violence is ingrained in the lives of these characters, and in the show itself.