False Things You Believe About Why Shows Were Canceled

The truth is not always stranger than fiction — in fact, the truth is often quite boring. This, of course, Just Won't Do — human brains require reason, rhythm, and some kind of narrative. This often means constructing one when none are presented, or at least fabricating something that's more compelling. This is especially true when a beloved television series gets canceled. Surely there's a reason why this beloved show got the axe while so many less deserving shows are still running?

It's not just internal belief that propels this, thought: sometimes networks often get involved and make their own spin. Maybe the real reason is too embarrassing and they need a grand narrative, or maybe it's a death-by-a-thousand-cuts scenario where there's no obvious scapegoat. Other times, we all spin a reason years after a show's been off the air. Ratings are hard to come by for shows from certain eras and easy to overlook when we have them — sometimes people just want a reason why a show stopped besides "it was canceled after it hit the syndication threshold." Either way, there's a lot of false things people believe about show cancellations, and we're here to set the record straight.

Happy Days ran for years after Fonzie jumped the shark

It's hard to imagine TV without reruns of Happy Days, but if they ever stop running, the phrase "jump the shark" will remain. Named after an absurd stunt in season five episode "Hollywood: Part 3" where Fonzie straps on water skis and jumps over a shark, the idiom refers to the point where a show does something that marks a decline in quality.

Here's the thing: for Happy Days in particular, the shark jump wasn't even close to the beginning of the end. It wasn't even the beginning of the middle. It ran for years afterwards.

Happy Days was never a critical darling, so the idea that reviews went down afterwards is hard to substantiate. Also the phrase "jump the shark" was coined circa 1985 — at least one year after Happy Days ended and nearly a decade after the episode in question. Having such a moment marked in hindsight instead of contemporaneously shows this as more of a thought experiment than a hard and fast rule. The franchise also had a number of important events occur after the jump, including the introduction of Mork from Ork and a half dozen spinoffs.

Fred Fox Jr., who wrote the episode, made an airtight point in the L.A. Times: "It was the 91st episode and the fifth season. If this was really the beginning of a downward spiral, why did the show stay on the air for six more seasons and shoot an additional 164 episodes? Why did we rank among the Top 25 in five of those six seasons?" MeTV even offered their own list of more accurate alternatives, including Fonzie working as a teacher and kissing a nun.

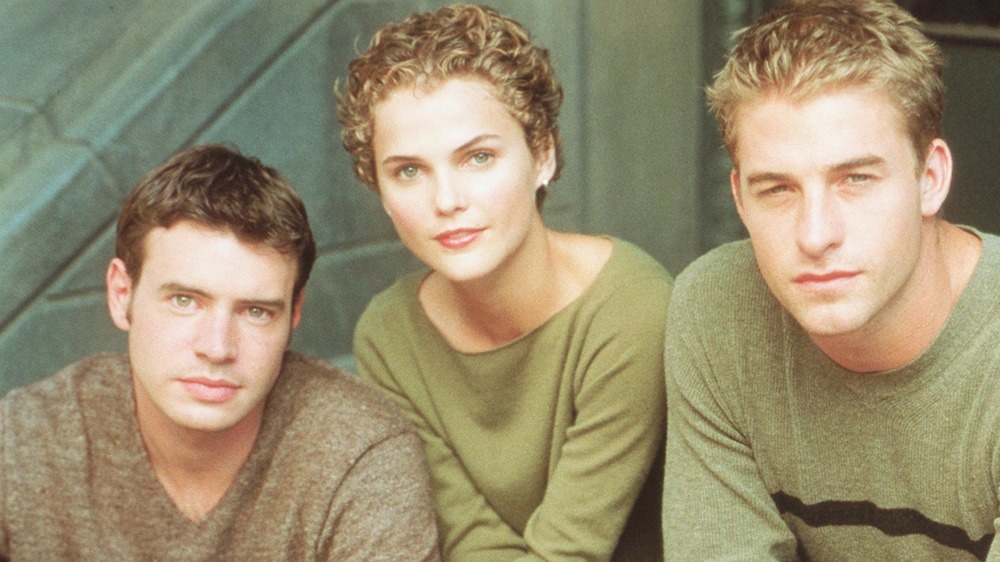

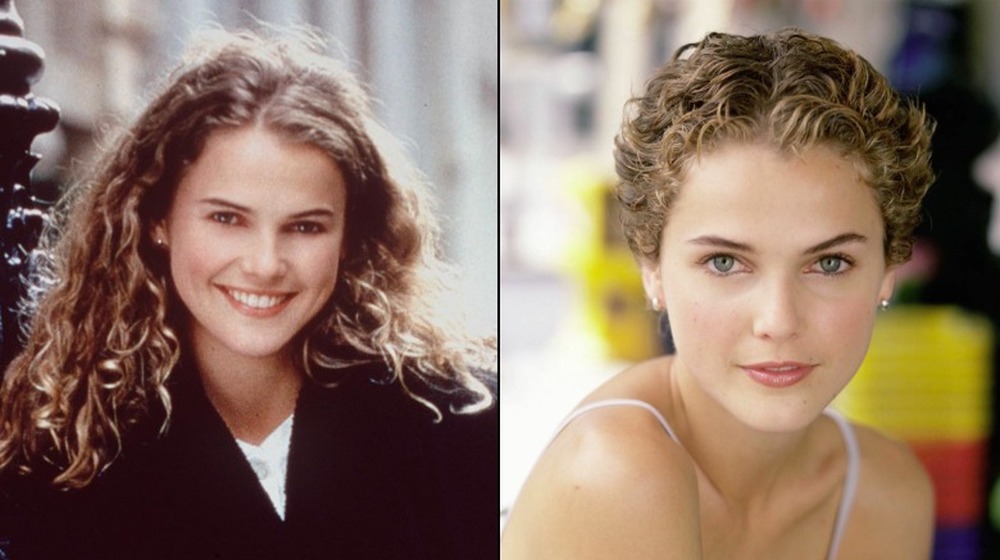

Felicity lost most of its viewers before the haircut

Years after Felicity left the airwaves and the WB turned into the CW, it's still remembered for one event: The Haircut. More than any character, plot point, or storyline, Felicity's iconic hair getting trimmed into a weird sort of pixie cut has defined the series. It's been a source of pop culture derision since, and it's popularly considered the moment that killed the show. There is a modicum of truth to this — there was enough fan backlash that executive producer J.J. Abrams took "full responsibility for the idea of cutting her hair" in the press. But only a modicum, and it's become a scapegoat for the real problems: changing time slots and weaker stories.

First, the time slot. Felicity was broadcast on Tuesday evenings during the first season, prime TV real estate for the late '90s. The second season saw the network move it to Sunday nights, a much weaker time slot. Second, the storylines were underwhelming, an opinion held by both fans and creatives working on the show. Abrams admitted this at the time to the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, saying that there was "a crucial period of four or five episodes where we told stories that were a little unfocused and it didn't feel as compelling as it should have."

That "four or five" is important, because the Haircut happened in episode five. It might have shocked some fans, but the show was already losing viewers — and it's easier to blame a single event than a series of bad decisions. What's also lost: that wasn't the end of the series. Felicity finished the season, saw a ratings bump the following season after moving to Wednesday, and wrapped after four seasons with a proper finale.

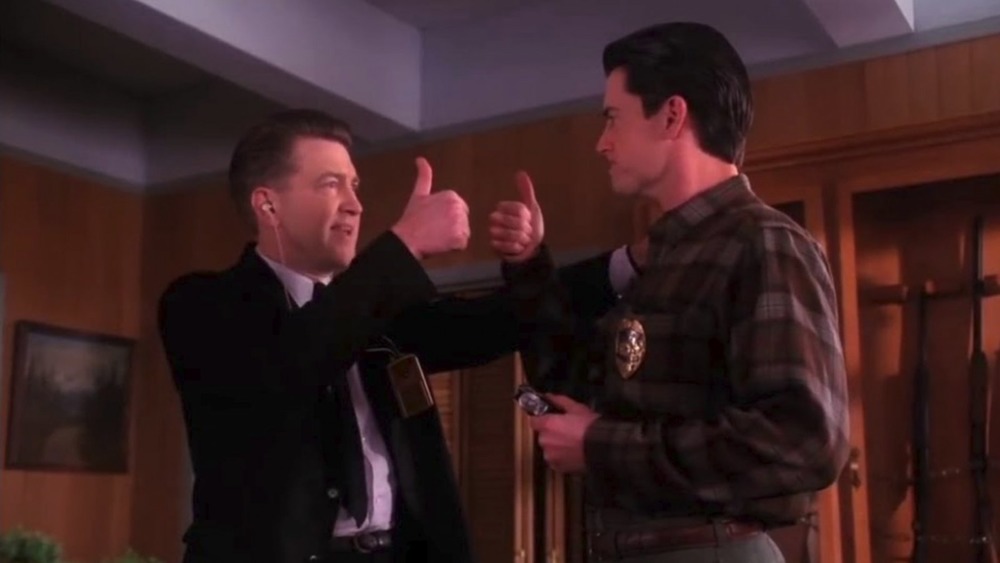

Twin Peaks lost ratings due to bad time slots and the Gulf War

The arc of Twin Peaks as a show, from debut to cancellation, is often summed up thusly: the first season was a smash hit, the network forced the show to reveal the killer early after dwindling interest, and the rest of season two just wasn't that good. Every part of this is at least partially true, and there were other factors that fed into it — such as a behind-the-scenes feud that killed the planned Audrey-Cooper storyline. But this all leaves out maybe the most important reason for the ratings drop: time slot shenanigans.

The first episode of Twin Peaks, broadcast on a Sunday, nabbed monster ratings — partially due to America's Funniest Home Videos being the lead-in. Ratings stayed solid enough after it moved to Thursdays, but there was a clear decline in viewership after four episodes — a fact noted contemporaneously by the New York Times.This was due in part to ABC scheduling Twin Peaks against Cheers, a well-established powerhouse of a show. Cheers was also episodic instead of serialized like Twin Peaks, meaning that someone who missed an episode of Twin Peaks might be more willing to cut their losses in an era before DVR.

The situation was made worse in season two: the show was moved to Saturday nights, one of the worst time slots on all of TV. Series co-creator Mark Frost brought up another obstacle during an interview on WFDU: the show kept getting preempted by coverage of the Gulf War, a huge moneymaker and ratings getter for TV at the time. Between the bad time slot, the preemption, and the serialization in an era when that wasn't common, the show was going to lose viewers regardless of its content.

Cousin Oliver didn't kill the Brady Bunch

The mere phrase "Cousin Oliver" inspires snarled lips and looks of derision among sitcom aficionados. Brought in during the last season of The Brady Bunch, he was meant to replace some of the cute factor that was lost after the youngest kids aged up — but instead ended up a cloying presence. None of this is a knock on actor Robbie Rist, who was just a kid and went on to have a solid career in music and voice acting. Nonetheless, "Cousin Oliver" is now shorthand for when shows bring in something cute to liven up a dying show, and is often credited with killing a popular sitcom.

There's just one problem with that theory: The Brady Bunch was not popular during its original run, not by any meaningful metric.

That's not to say that the show didn't have fans or regular viewers, but those are harder to track. What's easy to track is Nielsen ratings, and at no point during its five-season run did it crack the Top 30, peaking at 31 in season three. The final season was rated 55th out of a possible 80 shows, and at that point no cast addition or subtraction is going to make a difference — and it's unfair to blame a kid, albeit an obnoxious one, who was only there for a handful of episodes. There's also a decent chance ABC wouldn't have wanted to continue anyway: not only were the kids getting older, they had enough episodes for syndication. If so, that plan worked beautifully: it became a monster hit and TV staple in reruns, never leaving the air and kickstarting a new franchise.

Dungeons & Dragons ended due to declining ratings, not protests

The 1980s Dungeons & Dragons cartoon came out at the height of the game's popularity — at least before every podcaster on planet earth decided they should record their own D&D game — and was a big hit for a few seasons. It also attracted controversy, almost entirely because D&D was one of the targets of the 1980s Satanic panic. The most prominent of these objections came from the National Coalition of Television Violence, who petitioned the Federal Trade Commission and Consumer Protection Agency to put a warning on all D&D properties — including the TV show — that they were linked to violent deaths. These requests were rejected. There were other concerns about the level of violence, and there was one script that was pulled in part because it was too violent for their liking.

Between the D&D panic and the concerns about violence, the fact that the show ended with an unresolved storyline after three seasons fed into two rumors about its cancellation, both of them false. First, that the missing episode showed the kids suffering an awful fate — often listed as being stuck in Hell after dying. Script writer Michael Reaves shot this down hard on his blog.

Second, that the show was canceled after protests. Mark Evanier, who developed the show for television, dismissed that on his blog, explaining "The Dungeons & Dragons series was cancelled due to declining ratings. I keep reading stories about it getting yanked off the air because it was too 'violent' or because protest groups thought it was Satanic or something of the sort. As far as I know, the protests were minimal and had no impact. The show simply began losing its audience, as all shows eventually do."

Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C. wasn't part of the Rural Purge

Television in the 1950s and 60s was defined by shows taking place in rural areas and small towns. Green Acres, Petticoat Junction, The Beverly Hillbillies, and more than a few shows about the town of Mayberry ruled the airwaves — and that's just scratching the surface. Then there was a sea change around 1970, when networks saw urban shows like All in the Family and Mary Tyler Moore draw great ratings and bring a new level of respectability and sophistication to the networks. By the end of the 1970-'71 TV season, most of these country-themed shows were unceremoniously canceled in what's been dubbed the Rural Purge.

One such show that wrapped during this era was Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C. – and, given its connection to Mayberry, is often incorrectly listed as getting canceled as part of the Rural Purge. This is false — star Jim Nabors left the show in 1969 after five wildly successful seasons simply because he wanted to do something else. Nabors saw himself as more of an entertainer than an actor, and as such he built a variety show after leaving his show. There was, however, one related show that got axed: Mayberry R.F.D., the last connection to The Andy Griffith Show remaining. It's likely Mayberry R.F.D. and Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C got conflated and a misconception was born.

Zoey 101 wrapped before Jamie Lynn Spears got pregnant, not because of it

The final season of Zoey 101 was shown under the spectre of one of Nickelodeon's biggest controversies: star Jamie Lynn Spears becoming pregnant at age 16. Given that she announced her pregnancy in December of 2007 and the fourth and final season began January 2008, many see the two events and assume one led to the finale of the other. This is false — the two events were independent of one another.

Series creator Dan Schneider gets asked "did Zoey 101 end because Spears got pregnant" a lot, so much so that he put the answer on his blog's FAQ page. He made it clear: they didn't even find out she was pregnant until later. "The last season was shot during the summer of 2007, and wrapped (ended) in August," wrote Schneider. "We had our final wrap party at the end of August. Everyone had a fun time, hugged, and we all said our goodbyes. That was the end of Zoey 101, in terms of production. It wasn't until several weeks later (in October) that anyone from our production heard about Jamie Lynn being pregnant." He also said the show ended because Nick had enough in the can for reruns and everyone was ready to move on.

Strangers with Candy wasn't canceled 'too soon' because it was never canceled

Strangers with Candy frequently appears on lists of shows canceled too soon. Running for 30 episodes between 1999 and 2000, the show had a murderers' row of comedic talent — Amy Sedaris, Stephen Colbert, Paul Dinello, and Janeane Garofalo — and a strong cult following. Fans rejoiced when a prequel film came out in 2005 starring all the original cast. During the press tour, Sedaris revealed something that didn't get much attention then, nor has it since: the show was never canceled at all.

In an interview with the Austin Chronicle, Sedaris unequivocally stated that at no point was the show ever canceled. "We wanted to go out; we wanted a final episode because usually Comedy Central does things in three seasons, so we kind of figured we had three seasons. We thought if we were going to do it again, yeah, we could write 10 episodes or not write 10 episodes." They just stopped making episodes, figuring that their time was up anyway.

The Wonder Years ended because of a lawsuit, not star aging out

The Wonder Years came to a natural conclusion, both in the show's continuity and with real life circumstances. In the show, Kevin and Winnie's relationship comes to a passionate close and everyone is ready to move on to their next chapter. In real life, all of the young actors were getting older and the show had to wrap up sooner rather than later. But according to at least one source, these aren't the true reasons the show ended: the blame lies with a lawsuit.

During the final season, the show's former costume designer Monique Long filed a sexual harassment suit against stars Fred Savage and Jason Hervey, claiming she was let go from the show after rebuffing their advances. Abbey Mills, who played Norma Arnold, revealed in a 2018 interview with Yahoo! Entertainment that the PR nightmare that would have resulted led the show to make the final episode of that season the series finale instead of hanging on for another year. Mills called the suit, which was later settled out of court, "completely ridiculous." Savage says he was "completely exonerated," but Long stands by her claims. Either way, there's credible reason to believe this legal action had more to do with the show getting axed than Savage turning 17.

Conan's Tonight Show couldn't have possibly been losing money

One of the central narratives NBC pushed in the wake of the 2010 Tonight Show conflict was that Conan O'Brien's run as the host of the show led to the long-running franchise losing money for the first time in its history. Somehow, despite all the public examination and re-litigation, this point has stood — often with the caveats of "O'Brien would have brought in more money if you gave him a chance" or "he had a bad lead-in." Here's the thing: even without those caveats, it's mathematically improbable — if not impossible — for the show to have lost money even in that small sample size.

For starters, television isn't about having the most viewers, it's about having the right viewers. While O'Brien's Tonight was drawing fewer overall viewers, he outperformed Leno's tenure in the lucrative 18-49 demographic — a surefire sign of better ad buys and high revenue. Speaking of revenue, lower revenue doesn't mean unprofitable: O'Brien's Tonight had similar ratings to The Late Show with David Letterman, a show that cost more and was still profitable. O'Brien's salary was also estimated to be much lower than Leno's — $12-$15 million compared to Leno's $30 million. On top of all this, talk shows are so durable because they're among the cheapest television shows to produce, and the mere idea that the biggest name show in late night would lose money is laughable.

O'Brien told 60 Minutes that NBC's claim about Tonight losing money was "not possible," a sentiment echoed by late night experts and experts consulted by The Wrap. O'Brien reasoned in Bill Carter's book The War For Late Night that NBC could have only decided the show was unprofitable if they factored in construction of new offices and sets, which is a stretch to say the least.