The Untold Truth Of Citizen Kane

Everybody has their own idea of the greatest movie ever made, but few have been as universally agreed on as Citizen Kane. The classic story of a reporter trying to piece together the story of a multimillionaire after his death — and the meaning of his last words — has endured over the years since its release in 1941. It topped a survey of hundreds of critics and filmmakers by the British Film Institute's magazine Sight and Sound for decades until Vertigo finally knocked it out in 2012. And it's still number one on They Shoot Pictures Don't They's survey of even more sources. As Netflix and David Fincher's Citizen Kane-inspired film Mank shows, the stories behind the scenes of a classic film can be just as exciting as the ones we see onscreen. Even if you're a fan, Citizen Kane's backstory is so rich that there's always more to discover. Here's just a few examples.

Orson Welles did the impossible because he didn't know it was impossible

Citizen Kane became a classic not just for its story but also for the way director/star Orson Welles told it. He shot the action from angles few directors had thought to use before. And he revolutionized "deep focus" photography, which allowed both the foreground and the background to appear clearly.

All that technical wizardry is even more incredible when you consider Orson Welles had never made a movie before — his background was in theater and on the radio. When talk show host Dick Cavett asked how he knew he could achieve deep focus, Welles answered, "Because I didn't know any better. It comes from sheer dumbness!" He said that was exactly what allowed him to innovate the way he did. He wasn't used to the limitations of the era's cameras, so he simply didn't understand why everything couldn't be in focus at once.

Welles told Peter Bogdanovich that Gregg Toland, one of the most in-demand cinematographers in Hollywood, volunteered to shoot Citizen Kane because he knew working with an outsider would give him an opportunity to look at filmmaking in a new way, and he was skilled enough to deliver on Welles' impossible demands. Welles was so impressed that he made sure Toland's name was just as prominent as his in the credits.

Citizen Kane brought ceilings to film sets

One of Welles and Toland's biggest innovations was their frequent use of low angles that made the actors loom above the camera. Many critics have observed that you never saw a ceiling in the movies before Citizen Kane. There's a reason for that. Most movie sets at the time were built without ceilings. Studios used the space where they would have been to set up lighting, microphones, and other filmmaking equipment.

But ceilings were important to Welles: He told Bogdanovich he wanted to show them in Kane because "The simple thing is that movies still go on telling lies... they pretend there's no ceiling — a big lie in order to get all those terrible lights up there. You can hardly go into a room without seeing a ceiling, and I believe a camera ought to show what the eyes see normally looking at something."

Welles also said he needed to shoot from below to keep the movie interesting: "I had more low angles in Kane just because I became fascinated with the way it looked... there are an awful lot of dull interiors — Kane is full of them — which are by their nature not very interesting and look better when the camera is low."

But Welles still needed all that equipment that would normally be hidden above the actors. In order for them and the ceiling to coexist, Citizen Kane didn't use real building materials that would block light and sound. Instead, it used muslin fabric, which was thick enough to hide the instruments but thin enough that they could still work.

Not everything you see is actually there

Citizen Kane had a relatively low budget — $800,000, or about $15 million in 2020 money. And yet its sets are just as impressive as any big-budget blockbuster, even though only $5000 (about $90,000 today) was set aside to build them. For instance, there's Xanadu, Kane's lavish Florida estate, an awe-inspiringly cavernous space full of expensive artifacts Kane's collected from around the world. The sets aren't just impressive, there are plenty of them: Set designer Perry Ferguson said in the premiere program there were over a hundred, twice as many as he'd ever built before. He was able to deliver all these locations through cinematic trickery. He explained to American Cinematographer that "We [made] a foreground piece, a background piece, and imaginative lighting suggests a great deal more on the screen than actually exists on the stage... Sets like this will be planned just for those angles and no others." So while you might think you see a whole room between these two set pieces, there's nothing there but movie magic. Is it any wonder Orson Welles later became a magician himself?

Dorothy Comingore quit acting for years because she couldn't find a script this good

Inside the great tragedy of a great man, Citizen Kane also includes the equally powerful small tragedy of an ordinary woman with Dorothy Comingore as Kane's second wife, Susan Alexander. Kane falls in love with her when he meets her on the street and she doesn't recognize him. But instead of embracing the ordinariness that drew him to her, Kane tries to raise her to a level of greatness she can't achieve and doesn't want, forcing her against her will to become an opera diva, driving her into anxiety and finally a suicide attempt.

Comingore didn't make many film appearances after Citizen Kane, and it's hard to believe the actor behind such a towering performance could disappear so completely. Welles explained why: "She turned down every offer she got for three years... She was waiting for another part like that." But there are other, sadder reasons Comingore's career never took off as well. The terms of her contract with RKO kept her from finding work with other studios. When she missed several days of work during a long illness, the studio suspended her, and she returned to work to find no other studio would hire her. Worst of all, her commitment to desegregation, unionization, and other progressive causes landed her on Hollywood's blacklist of suspected Communist sympathizers. Worse, her political positions were used as evidence against her in a trial for custody of her children, and possibly in her 1953 arrest for alleged prostitution as well.

Welles took the classic acting advice and broke a leg

One of the oldest acting traditions is that you should never wish another actor good luck, because then the opposite will happen. So to turn that around, you should wish for something terrible, and over the years that turned into the shorthand "Break a leg." Apparently, somebody must have wished Orson Welles good luck, because he actually did break a leg while filming Citizen Kane.

In one dramatic scene, Kane's political opponent, Boss Jim Gettys, arranges for Kane's wife to meet his secret lover and threatens to tell the press if Kane doesn't end his campaign for governor. Kane refuses, and as Gettys walks down the stairs, he leans over the bannister to shout back, "Don't worry about me, Gettys. Don't worry about me! I'm Charles Foster Kane!" and threatens to send Gettys to prison.

Welles really throws himself into this scene, and in one take, he threw himself all the way off the top of the stairs, falling ten feet to the ground and chipping his ankle bone in two places. Welles was able to return to work, but for the next two weeks, he directed from a wheelchair and needed metal braces to stand up for his scenes in front of the camera.

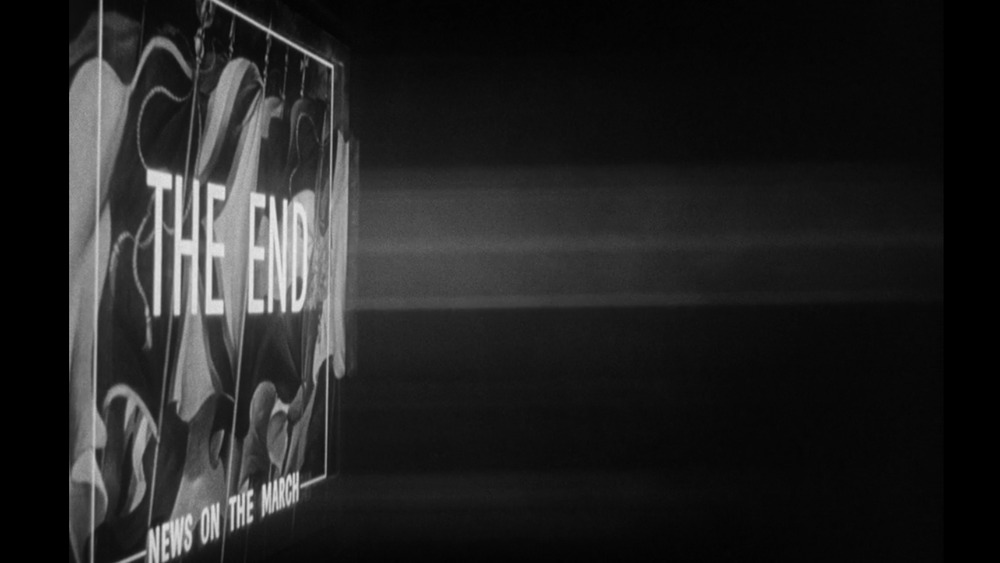

The Italian premiere audience booed the newsreel for looking too much like a newsreel

Another striking sequence from Citizen Kane is the news report that plays after the opening scene of Kane's death. Done in the style of the theatrical "newsreels" of the time, this sequence tells the story of the antihero's life more or less linearly, from the cradle to the grave, giving us all the background we need to follow the fragmented timeline the rest of the movie follows. And Welles' crew took great pains to make it look just like a real newsreel, scratching parts of it with sand and dragging others over concrete to artificially age it and using intentionally awkward edits and framing to make it look like it was created by journalists instead of filmmakers.

Unfortunately, they did too good of a job for at least one audience. Citizen Kane took years to arrive in Italy due to World War II, and Orson Welles recalled attending its first screening there many years later, where the audience thought they'd gotten a worn-out old copy of the film and started booing.

Welles was the only one allowed to see it until it was finished

Even though Orson Welles had never made a movie before, RKO Pictures gave him a contract that made even the most veteran directors jealous (in no small part because, as Welles told the BBC, he wasn't really interested in movies and made outrageous demands to get the studio off his back). At a time when producers were at least as involved in their movies as directors, Welles had total artistic freedom on the set. That freedom extended even after Citizen Kane was completed. Welles had the right of "final cut," meaning nobody but Welles and editor Robert Wise could re-edit the finished film.

The right of final cut is legendary in the story of Citizen Kane, but it's actually even more unprecedented than it seems. Welles told Bogdanovich that, until the movie premiered, no one else could watch any footage from it. If they had, things might have gone very differently. When the film finally did open, it became the subject of a long legal battle with real-life publishing tycoon William Randolph Hearst, who called Citizen Kane a work of libel for its resemblance to his own life. The producers panicked, and they were scared to show the movie in more than a few venues. If they'd seen it in progress, it might never have gotten made at all.

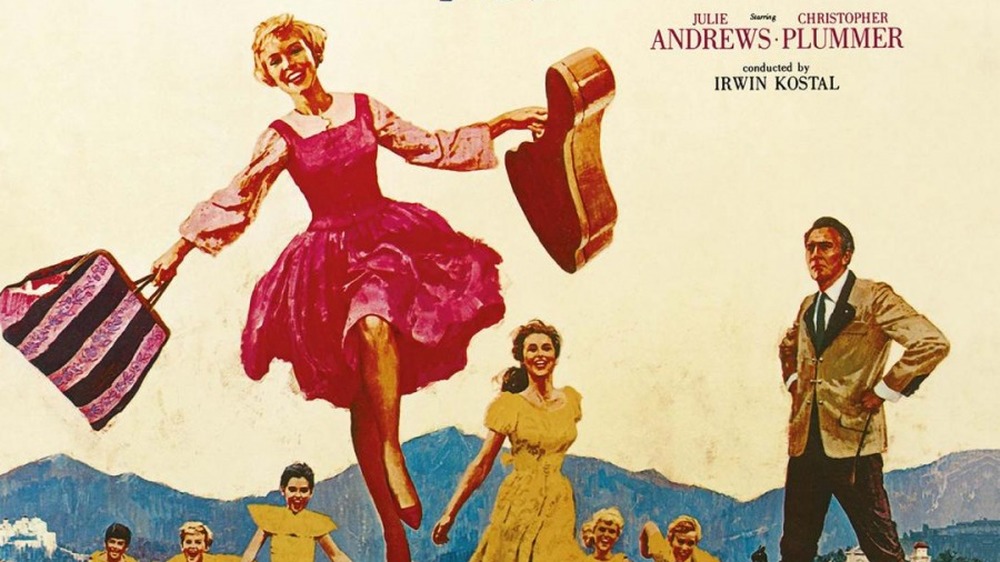

Citizen Kane is one degree of separation from The Sound of Music

Orson Welles had full control over his vision for the final edit of Citizen Kane, but the man in charge of executing that vision was Robert Wise. Like Welles, Wise was just starting out his career. He'd begun working in Hollywood doing odd jobs around the RKO studio before moving up to a position as sound editor, then assistant film editor. Wise had only been a lead editor for three years when Citizen Kane premiered, but his work on it was still recognized as some of the best to come out of Hollywood, making dizzyingly complex cuts that matched images and dialogue between scenes.

Wise worked with Welles on his next movie, The Magnificent Ambersons, and actually directed long sequences of it on his own when the studio demanded a happier ending. Wise began directing his own movies for legendary horror producer Val Lewton on the cult classic Curse of the Cat People, a sequel to Lewton's biggest hit. From there, Wise embarked on a long career as one of Hollywood's most versatile hitmakers, from the western Blood on the Moon to film noir like The Set-Up, returning to horror with The Haunting, and defining two very different eras of science fiction with The Day the Earth Stood Still and Star Trek: The Motion Picture. But Wise found his biggest success in musicals, directing two of the genre's defining hits with Sound of Music and West Side Story and earning himself a Best Director Oscar for each of them.

William Randolph Hearst tried to sink Citizen Kane with complex schemes and xenophobia

While Citizen Kane is recognized as a classic today, it premiered in very few theaters in 1941 to harsh reviews. That was all the work of one man, William Randolph Hearst, then the most powerful newspaper publisher in the country. Citizen Kane used him as inspiration for its title character, and he considered the whole film a feature-length attack on him personally. Orson Welles disagreed. If anything, he thought the film was too flattering, telling Peter Bogdanovich, "Kane was better than Hearst."

Either way, Hearst's attempts to attack and suppress Citizen Kane have become legendary. But if you do a little digging, you'll find some of Hearst's tactics were stranger than fiction. Some were so dirty even Kane would have been embarrassed of them, including preying on readers' xenophobia by smearing Hollywood for hiring immigrants and refugees and claiming Welles' production of the great Black writer Richard Wright's play Native Son proved he was a Communist.

But one story Welles tells would have been too sensational even for Citizen Kane: One night, a policeman warned him that a Hearst flunky had stashed an underaged girl in Welles' room along with a squadron of cops ready to arrest him for child molestation. All this scheming backfired for Hearst, forever tying him to Welles' movie. Once the most famous man in the United States, Hearst is now mostly remembered as the real-life Citizen Kane.

Welles tried to buy the movie himself

Hearst's vendetta against Citizen Kane kept it out of many theaters. The businessman owned many of them, and the rest were scared of his political influence. The major movie studios were panicking worse than anybody, and with Hearst threatening to topple the whole industry, they offered to pay RKO $800,000 to destroy every copy of the film.

Through it all, Orson Welles still believed in his movie, and he was willing to put up his own money to get it in front of the public. He told Peter Bogdanovich that if RKO wouldn't show Citizen Kane, he would buy the movie from them and show it himself. With so many theaters unwilling to book Kane, Welles even planned to set up tents to screen it in. But RKO refused, which Welles regretted even many years later, saying "I could have been independently wealthy for the rest of my life." He may be right: As new generations discovered Citizen Kane, its profitability went up, and at the same time, Welles' went down, and he spent most of his career in Europe barely scraping together enough money from odd places to make his movies. Who knows how many classics we missed out on because RKO wouldn't sell?

The US thought it was too communist and the USSR thought it was too capitalist

The smear campaign against Citizen Kane involved labelling Orson Welles a Communist, successfully enough that it got him on the FBI's watchlist. The Bureau dabbled in some amateur film criticism as a result, writing, "The evidence before us leads inevitably to the conclusion that the film Citizen Kane is nothing more than an extension of the Communist Party's campaign to smear one of its most effective and consistent opponents in the United States." One of William Randolph Hearst's underlings even sent his boss a memo claiming the filmmaker was "a front for the Communist Party!"

It's not a totally unfair reading of the film. After all, it's about a ruthless businessman who claims to support the common people but really just wants their devotion, who destroys the lives of everyone around him in the pursuit of material wealth, and dies realizing it was all futile. But apparently, nobody thought to ask the actual Communists what they thought of Citizen Kane. While Americans denounced the film for its negative portrayal of a successful capitalist, Welles told the BBC Citizen Kane had actually been banned in the Soviet Union because it wasn't negative enough.

The White Stripes wrote a whole song out of nothing but quotes from it

Whether you agree with critics' assessment of Citizen Kane as the greatest movie ever made, you'd have to look a long time to find one that's been more influential. It's been homaged, parodied, and written about more than you could read in a lifetime. Some of those tributes have come from some unexpected places. For instance, in 2001, the White Stripes released a bluesy rocker whose lyrics mostly come straight from Citizen Kane. Taking its name from the childhood flashback when little Charlie Kane shouts "The Union Forever" while playing Civil War, the track also includes singer/guitarist Jack White rapping the song from Kane's welcome party for his new reporters. White told Rolling Stone, "There's a song in the film, 'It Can't Be Love, Because There Is No True Love' at a party they have in the Everglades. I was trying to play it on guitar, and I went through the film and started writing down things that might rhyme and make sense together."

The Stripes never actually use Kane's name, replacing it with his initials in one line. That apparently wasn't enough to keep the copyright lawyers away, and Rolling Stone also reported that Kane's current owners at Warner Bros. threatened to sue. It's unclear whether that conflict ever made it to court. But if Orson Welles were still around to see it after all the legal battles he endured getting Kane to theaters, it's hard not to think he'd get kick out of it.