The Untold Truth Of Max Headroom

The arc for the Max Headroom character within pop culture is filled with unexpected left turns. Max moved from being a satirical commentary on American TV talking heads to become a full-fledged American TV talking head and a completely unironic TV pitchman — and then a nearly forgotten icon of 1980s media.

Nearly, but not quite. The stuttering, quip-dispensing gadfly of the broadcasting world "20 minutes into the future" was created when networks — both in the United States and Great Britain — were fixed institutions and televisions were firmly planted in the living room of the family home. Now people have televisions in their pockets all day long, anyone can upload an opinion piece to a video service, and as Marshall McLuhan once stated, the medium is the message.

Technology has caught up with Max Headroom, and in very tangible ways he lives among us today in the real world.

How did this character come to capture the zeitgeist in the late '80s, why did he fade from the spotlight so fast, and is there any chance he could make a comeback? This is the untold truth of Max Headroom.

The creators of Max Headroom

Britain's Channel 4 launched on November 2, 1982. Devised as an alternative to the taxpayer-funded BBC One and BBC Two, and commercial-funded broadcasting network ITV, Channel 4 lacked the deep pockets to produce high-budget programming. However, MTV had launched in America only two years prior, and music videos of the era offered visual appeal — and reasonable licensing fees.

The network's Commissioning Editor, Andy Park, joined forces with Terry Ellis, founder of the multimedia company Chrysalis, to develop a show that would also capitalize on this wealth of audio-visual material. They tasked producer Peter Wagg to pull a team together to make it happen.

Ellis was a key part of the equation, having founded the Chrysalis record label more than a decade prior. His roster featured artists such as Procol Harum and Jethro Tull, and later Pat Benatar, Huey Lewis and the News, and more. With his influence, more record labels could be drawn into this new venture, but there was a stipulation: Park and Ellis informed Wagg that wanted to avoid the "Veejay" model MTV had pioneered. Their concept was to look more abstract and rely upon purely visual ways to link the music clips together.

Wagg reached out to Rocky Morton and Annabel Jankel from Cucumber Studios. The duo made a name for themselves as music video directors, garnering acclaim for their work on the "Accidents Will Happen" clip for Elvis Costello, among others, and they could create the visual aesthetic, but there remained a need to introduce the clips. This would be difficult, given the "no talking heads" diktat from above. With the input of science fiction writer George Stone, the concept of a computerized talking head — one more inclined to skewer the medium rather than reflect it — emerged.

The divergence worked for Park... so well that he wanted a backstory about how the fictional character came to be.

Altered egos

In the documentary The Story of Max Headroom: Live on Network 23, George Stone stated the name "Max Headroom" came from the maximum height signs that hung in every parking garage in London, literally meaning the maximum height allowed for a vehicle to enter the facility. Through several conversations, Jankel, Morton, and Stone locked the story down, using as their narrative touchstones the films Network and Blade Runner.

American investigative journalist Edison Carter was a left-leaning firebrand who consistently provoked the ire of his superiors at the monolithic TV conglomerate Network 23. His reporting of injustices committed down in the dystopian city below created discomfort, but Carter was the network's biggest star. They couldn't fire him, even if they wanted to — preferably before Carter caught on to the network's latest innovation: a microburst commercial called a "blipvert" that packed minutes of marketing pitch into seconds onscreen. With this, the network could cater to far more sponsors in far less time, offering an unbeatable return on investment for advertisers.

Well, not completely unbeatable. Blipverts also had a nasty habit of making viewers' heads explode.

Carter broke the story but knew he couldn't reveal the network's nefarious plan from inside the building. Security attempted to apprehend him, but Carter made his way to a motorcycle in the garage. In a last-ditch effort to stop him, Network 23's technology manager lowered the barrier as Carter sped toward the exit. Believing that Carter might die from his injuries, the network's technology team attempted to extract his consciousness and upload it into their computer mainframe. They couldn't afford to lose their star, after all.

Carter didn't die. He also didn't lose his sense of right and wrong or the belief that there were proper ways of pursuing justice. These self-limitations were not shared by his new digital doppelgänger, who named himself after the words on the sign that smashed into Carter's face in the garage: Max Headroom.

Max chaos

The central conceit of the Max Headroom story is that it illustrates a fragmented mind. Journalist Edison Carter believes in truth and justice. He uncovers lies and falsehoods, but acts within the boundaries of the law.

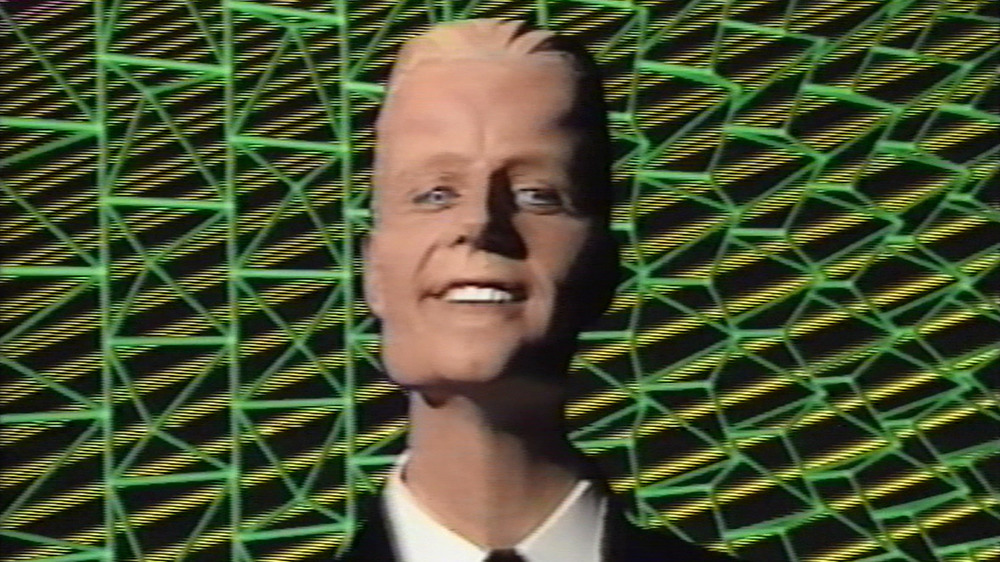

Max Headroom, on the other hand, has no constraints. His digital avatar jumps around all the programs broadcast from Network 23, and eventually to any broadcast anywhere. He disrupts and trolls, mocking the commercials that ostensibly pay for Network 23's programming and Edison Carter's wage. Max also has the freedom to drop uncomfortable truths the higher-ups attempt to keep buried. He's a digital graffiti artist tagging the side of the CEO's house like a rattle-can saboteur.

Rocky Morton and Anabel Jankel initially saw Max as being an ultra-conservative, the Hyde to Carter's liberal Jekyll. Somewhere in the production team's development stage, that changed. He was, after all, created to link music videos together, not to be a polarizing figure with the possibility of turning off half the viewing audience. In his final incarnation, Max Headroom was more of a firestarter than Carter's firefighter, but both were ideologically aligned.

Science fiction is often a palatable way of delivering difficult content to a public that might reject it otherwise. Twilight Zone creator Rod Serling was very transparent about this, saying the show's morality tales were refashioned as fantastic allegories to get them past CBS brass. Stories of white people confronting Black people or rich people taking advantage of poor people wouldn't fly, so Serling substituted in people versus aliens and the living confronting the dead.

Likewise, the Max Headroom series that eventually aired on ABC in the States dramatized oppressors against the oppressed. Average citizens could be kidnapped and sold for organ transplants on the black market. The potential of viewers exploding could be dismissed as an unintended consequence of getting better returns for corporate stakeholders. The television show looked like a nasty fever dream of tomorrow, but it was making sardonic comments about its present. And even though the show looks in hindsight like a product of its time, the storytelling is more relevant than ever.

Max goes to Hollywood

Channel 4 now had the backstory it wanted, and it was far too rich a concept to not exploit. A film was commissioned to precede the Max Headroom show proper. After consideration of the detail in the story, producer Peter Wagg recognized that it wouldn't be a cheap or cheerful project. He also stipulated that he wanted the program filmed in 35mm, not the less-expensive British TV standard 16mm. With Ellis' blessing, Wagg went to the United States to sell the project as a co-production.

According to Wagg in the documentary The Story of Max Headroom: Live on Network 23, it wasn't a long trip. HBO got word of the teaser reel and contacted him, saying if HBO could be the sole U.S. broadcast distributor of the film, they'd front the additional money needed to make it as envisioned. There was just one problem: The film was to be shot in the U.K. Edison Carter and Max Headroom were to be brash, in-your-face Americans, but money hadn't been allotted to do casting in the States. Luckily, Canadian-born actor Matt Frewer lived and worked in England. Before Max Headroom, he'd been in several productions, most notably The Crimson Permanent Assurance, the short film by Terry Gilliam preceding Monty Python's The Meaning of Life.

The production company now had its money and its Max, but it didn't have a shooting script. Writers were suggested to Wagg and he met with one, Steve Roberts, in a pub to discuss the idea.

"He was a suit and I hated him on sight," Roberts noted in the documentary. However, after some conversation and drinks, Roberts fell in love with the anarchic spirit of the character and the show. He said the subversive nature of the gig — essentially taking company funds and converting them into audio-visual broadsides against late-stage capitalism — appealed to him.

Max Headroom: 20 Minutes into the Future debuted on Channel 4 in 1985 and was a success. Its backbone of technology, corporate conspiracy, and dystopia melded into the cyberpunk movement in literature being pushed forward by authors such as William Gibson and Neal Stephenson.

It wouldn't be long before American broadcast television started asking if they could get in on this Max Headroom thing too.

Max goes to America

Throughout the mid-to-late '80s, the ABC network had a problem. NBC had the exciting, cutting-edge programs people were buzzing about. CBS had numerous shows with legacy viewership, as well as one of the most lauded news divisions in the industry. Aside from the odd hit like Moonlighting, ABC basically had The Love Boat and Battle of the Network Stars. They were in desperate need of a glow-up.

Enter Max Headroom.

With the Lorimar company taking the reins for the U.S. production, ABC took a chance on the property, although the core of the U.K. team — producer Peter Wagg, writer Steve Roberts, actors Matt Frewer and Amanda Pays — had reservations. Apart from the impact Max was making on pop culture, did ABC know what they were getting into?

Yes and no. ABC insisted on a domestic executive producer to act as a proxy for network brass, and Philip DeGuere, whose earlier credits included Simon and Simon and CBS' Twilight Zone revival, was hired. According to Wagg and Roberts, they were concerned DeGuere would be yet another company man holding them back, but the producer proved otherwise. DeGuere told Wagg he would let him know when things were getting too hot for the network, yet promised he'd always defer to Wagg's judgment. Still, there was tension between the Max Headroom production crew and ABC's Standards and Practices department. Often, stated Roberts, they'd sneak in their subversive viewpoints without question because the overseers just didn't get the joke.

Bigger wasn't better

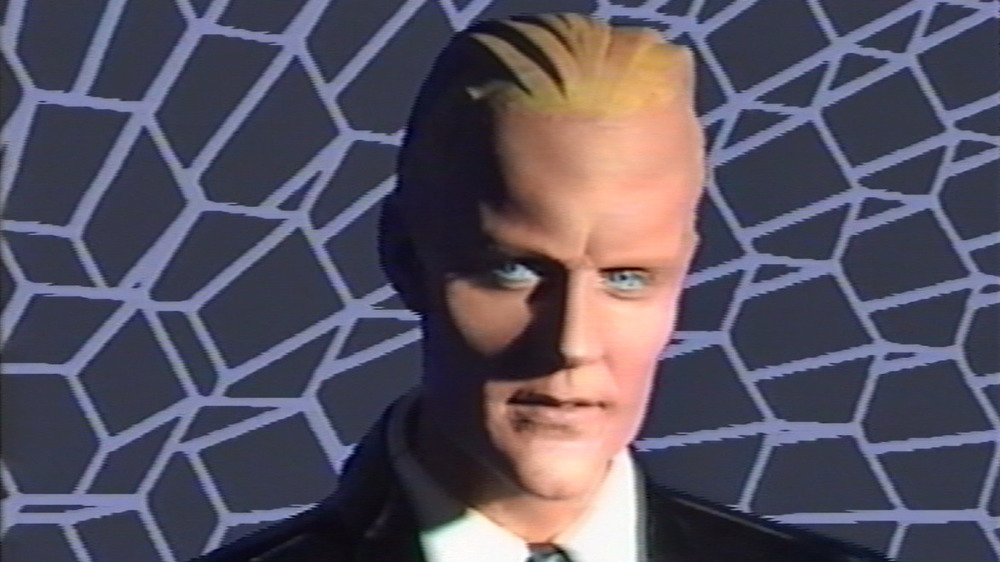

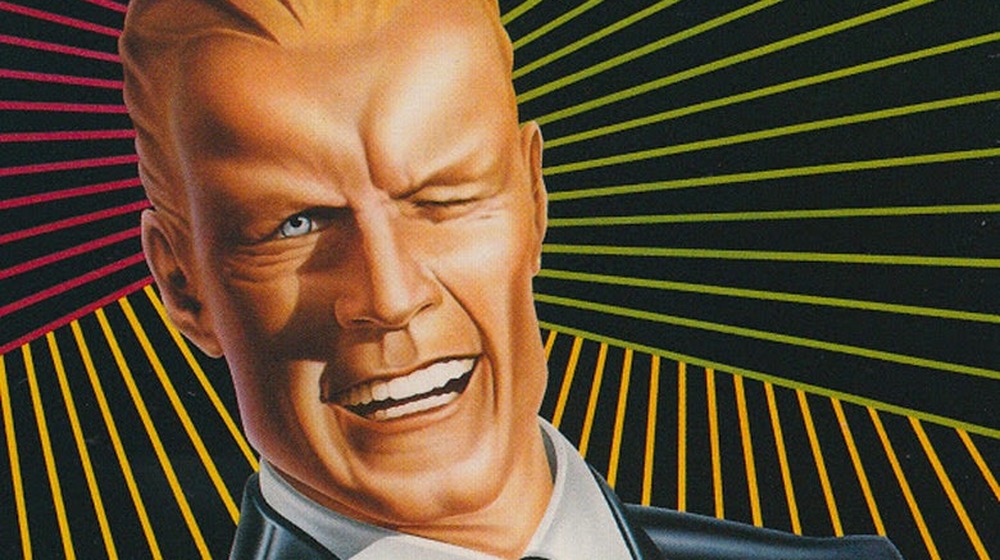

ABC didn't get the response it expected from Max Headroom. Besides the tooth-pulling required to keep the show from offending an unprepared audience, the program was expensive to produce. This was well before the advent of reliable computer graphic technology, and nearly everything had to be a practical effect. Even Max himself was a fake-out — actor Matt Frewer, wearing makeup and prosthetics, filmed the character's segments in front of abstract animations. The footage was altered and degraded afterward to create Max's concussed stutter and janky movements.

Even worse, people were growing tired of the character. Max was made the spokesperson for the introduction of the disastrous New Coke. Frewer — in character — became a regular on talk shows. He wound up in the song "Paranoimia" by the new wave collective the Art of Noise. He was overexposed. Meant as a commentary against "the business," Max himself was becoming a company man. One year after the series ended its brief run in May of 1988, he was parodied in Back to the Future II.

The show went off the air with several scripts left unproduced. One notable casualty was "Xmas," written by another Twilight Zone ex-pat, George R.R. Martin — now known worldwide as the author of the book series that inspired HBO's Game of Thrones.

Max Headroom for President

The Max Headroom series sputtered out quickly on American television, but once a corporation catches a whiff of profitability from an intellectual property, it's typically reluctant to let go — as evidenced by the short-lived talks for a Max Headroom movie that started up just as the show was dying down.

Titled Max Headroom for President, the film would have been rushed into production in early 1988, in order to capitalize on a presidential election season that had already seen presumptive front-runner Gary Hart abandon his candidacy in the wake of a sex scandal. Politics and tabloid news were closer than ever, so Max's gleeful boundary-busting antics seemed like a natural fit for the times. Saying it was "basically going to ride the coattails of the presidential campaign and do it as sort of a reality thing," Frewer later recalled, "There was an actor who was president... why not a computer-generated man? Like a lot of these things, it never made it to first base."

"I got interest," said Wagg, "but I never was able to get it over the line, and then I just kind of moved on myself."

Graduating from Max Headroom

In the years since the show's cancellation, the cast and crew behind Max Headroom have gone on to a wide array of other projects. Matt Frewer went on to co-star in the Disney film Honey, I Shrunk the Kids, the television series Orphan Black and Altered Carbon, and reprise the role of Max in the movie Pixels — to name just a few of the credits he's racked up over the last several decades.

Max Headroom marked an early appearance for Jeffrey Tambor, who would later earn acclaim for his roles on The Larry Sanders Show, Arrested Development, and Transparent. Amanda Pays, who portrayed Edison Carter's Network 23 counterpart Theora Jones, had a reccurring role on the television series The Flash (2014-2016) as Dr. Christina McGee.

Writer Steve Roberts, meanwhile, later worked on the shows The Real Ghostbusters, Darkwing Duck, and Hercules: The Legendary Journeys, while Peter Wagg joined the Cirque du Soleil organization as executive producer for a series of programs in conjunction with their stage shows. Michael Cassutt continued writing for television, notably contributing scripts to the series SeaQuest DSV, Stargate SG-1, Farscape, and Gene Roddenberry's Andromeda, among others. His focus eventually moved toward science fiction novels and short stories.

Rocky Morton and Annabel Jankel continued working in music videos and were the team behind the big-screen adaptation of Super Mario Bros. starring Bob Hoskins, John Leguizamo, and Dennis Hopper. Jankel's most recent directorial effort was the film Tell It To The Bees (2018).

As for Max Headroom himself? He's endured on the fringes of pop culture. In 2013, for example, Eminem played the character in the video for his song "Rap God."

We are all Max

These days, few may be able to identify any direct impact the character of Max Headroom has made on the world, but make no mistake about it: We're living in Max's reality.

Television is no longer tied to the living room. It's on every laptop, PC, and smartphone. The content is freed from the quaint structures of 1980s broadcasting. Gadgets that record biometric information like how many steps one takes in a day and what their heart rate is? That's not science fiction anymore. Neither is the notion that advertising is following you. Your devices know a lot about you, and thanks to our relationships with monoliths like Amazon, Google, and Netflix, we willingly deliver that information to marketers.

Big-ticket entertainment is hardly extinct. The Walt Disney Company has a chokehold on media through its film productions, the Disney+ streaming service, and billion-dollar acquisitions like Pixar, Lucasfilm, Marvel, and Fox. It even owns ABC now. The irony is that, in our present day, Disney's omnipresence can look an awful lot like Network 23.

Max.headroom.exe

One of the key beats from the Max Headroom television series was the character's inclination to jump into a variety of programs to disrupt and harass. In the mid-1980s, the thought of a sentient digital entity traversing content as if these were islands was novel. After all, digital broadcasting and streaming were decades away, as was The Matrix and the global conversation about the world within the mainframe.

Cut to today, into a world dominated by screens, all wireless yet still connected. Your home is protected by an internet-connected security system. Your car "talks" to satellites to geo-locate your position. Implants inform doctors of your present condition and can alert when they are prone to fail.

Into this brave new world comes the rise of artificial intelligence (A.I.), programs that communicate with us, play Jeopardy! against us, can write stories and music that feel unnervingly human, and may one day insist upon self-determination and autonomy. Should that come to pass, who could say such new forms of life would be benevolent?

The audience saw this coming in the '80s. After all, in its broadest definition, Max Headroom is a virus, infecting programming through his trolling. He speaks to the medium and through the medium, all while altering it. He's the ego (sometimes the id) to Edison Carter's superego, let loose in the form of an A.I.

Viewers could have dismissed it as satire at the time, but the world has caught up — and may yet need to reckon with a piece of free-floating code with a mind of its own.

Max Headroom: Another 20 minutes into the future?

Max Headroom was a show ahead of its time — a network series, airing in the waning days of the monoculture, savagely lampooning the chillingly logical endpoint of a society buckling under the demands of corporate capitalism. In hindsight, it's somewhat amazing that the show ended up on the airwaves at all. But in the years since Max Headroom's cancellation, what once looked like an absurdly dystopian view of the future has come to seem eerily forward-thinking in many ways — and now that viewers have more streaming services than ever to choose from, niche shows are able to thrive with far lower ratings than the numbers that drove Max off the air.

So could there be a Max Headroom reboot on the horizon?

It'll definitely be more than 20 minutes into the future before it happens, but the short answer to that question is a qualified "maybe." Matt Frewer has acknowledged that talks have taken place, telling StarTrek.com in 2013 that a limited series was a possibility. "It's not taken shape yet. It's very early days," he cautioned. "We're still talking. Hopefully it'll transpire."