Things You Get Wrong About James Bond

Long before audiences packed cinema seats to witness Thanos disappear half of existence in Avengers: Endgame, they gathered to watch one of the other longest-running cinematic franchises: James Bond. With its intrigue, slick '60s wardrobes, deadly bowler hats, piranha drawbridges, and stylish opening credits so inspired, they pull in musical cameos from the likes of Paul McCartney, Alicia Keys, Jack White, and Adele, it's no wonder the James Bond franchise has endured for decades. James Bond is plainly, classically cool, in a way that spans generations. Really, who doesn't dream of taking a spin in his Aston Martin? Haven't we all imagined asking, cool as a cucumber, for a martini shaken, not stirred?

Not all Bond movies are created equal, however: Many of them drift dramatically away from some of the source material's key characteristics, while others add in some of the franchise's most beloved features. As a result, even the most diehard fan can get a bit confused when it comes to the truths of the Bond mythos. Said fans are faithful enough to deliver the series a gross box office of over $7 billion worldwide, however, so we're thinking they're more than deserving of some demystification. These are some of the things even devout disciples of James Bond get wrong about his complex world, from the super spy's real-world roots to his favorite roadsters.

The reboot that got back to James Bond's roots

In 1962, the late and larger than life Sean Connery set the bar for all Bond performances to come. His Scottish bravado, penchant for over-the-shoulder judo throws, and quips sharper than his white tuxedos defined the character for multiple generations of viewers. Yet his performance isn't actually by-the-book — by which we mean Ian Fleming's James Bond novels. In the films, from the 1960s through the 2000s, Bond is played more as an idea than as an individual man. There's nothing wrong with shooting first and quipping later, but this all-suave, all-the-time spy isn't exactly what Fleming had in mind.

It wasn't until Daniel Craig took up the mantle for 2006's Casino Royale that Fleming's Bond's mix of steely cool and the internal turmoil, caused by a job that comes with a license to kill, appeared on the big screen. Craig takes a different approach than Connery and his followers, and colors in Bond's interior. His Bond reads like he's almost reluctant to do the job, and the Vesper martinis are the only thing that keep him hanging on. Craig's turn gives the character something he doesn't have in previous movies — a character arc. In so doing, he gives the audience brief, potent glimpses into the world's most dangerous spy. This is much closer to the man Fleming presents in his novels, and it makes for some killer movies.

SMERSH vs. SPECTRE

The Special Executive for Counter-Intelligence, Terrorism, Revenge, and Extortion, or SPECTRE, plagues Bond throughout his cinematic history. However, Fleming didn't introduce the organization into his own series until after he sold the film rights. Pre-sale, Bond's exploits were rooted firmly in Cold War espionage. These novels follow 007's conflict with KGB knock-off Spetsyalnye Metody Razoblacheniya Shpyonov, or Special Methods of Spy Detection in English. They are more commonly known as SMERSH.

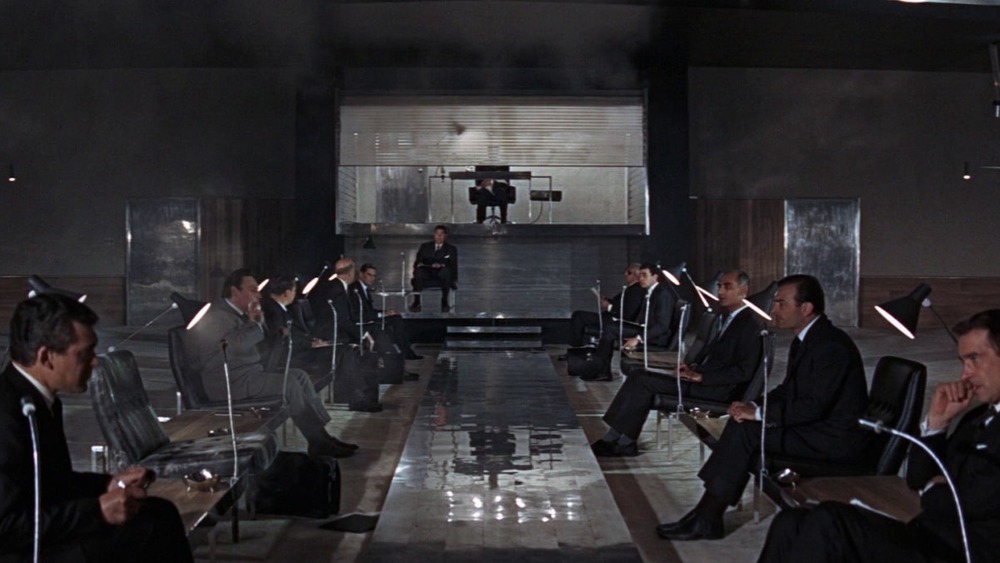

SMERSH backs Auric Goldfinger in the book bearing his name, and sets a honeypot for Bond in the original From Russia with Love. But when Fleming saw the Cold War starting to cool off, he decided to create a new organization, unaffiliated with any nation state. While it's a shame such a large part of Fleming's work never made it to the big screen, it's hard to argue that SPECTRE isn't more suited to film. With its numerically ranked members, schemes that often revolve around stealing or selling rockets, and its cat-stroking leader, SPECTRE sets the gold standard for privatized evil on the silver screen.

A fraternal twist

2015's Spectre delivers a fraternal twist to its audience. Spoiler alert: James Bond's arch-nemesis and the "author of all [his] pain," Ernest Stavro Blofled, is none other than Bond's own surrogate brother. In the books and the movies, Blofled is the enigmatic and megalomaniacal leader of SPECTRE. Unlike the books, however, the cinematic Blofled, played by the fiendishly polite Christoph Waltz, reveals himself to be the son of the man who took Bond in after Bond's parents died in an accident.

It's a surprising twist, as none of this material, except Bond's orphan status, is from the novels. Waltz's delivery of the familial gut punch comes mid-supervillain monologue, which is, of course, a necessary element of any Bond film. The twist shakes up the old-fashioned bad guy reveal — until Bond breaks out of his convoluted death machine, of course, which is a Bond trope as old as his trademark tuxedo. Some fans may have hoped Blofeld would stay true to his ex-spy roots from the page, or remain the rarely-seen presence delivered by the likes of Donald Pleasance in the '60s films. But Waltz's turn and Blofeld's retconned history brings something entirely new to recent Bond films, and that's a worthwhile choice. He's something totally unexpected from a very old part of Bond's past, and that makes him terrifying.

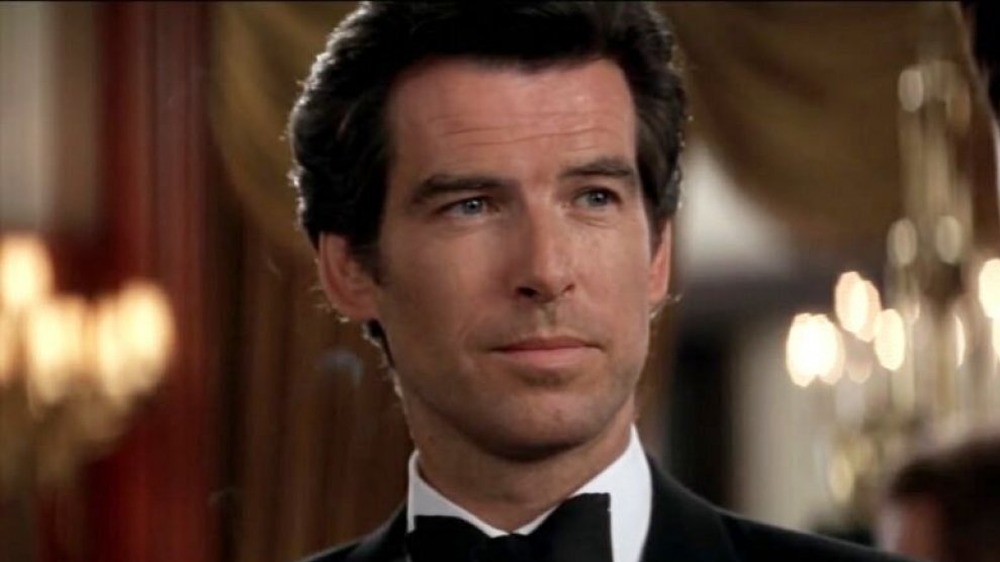

Pierce Brosnan brings Bond into the '90s -- and off the page

After Timothy Dalton exited the franchise in the '80s, there was major speculation as to who would pick up the mantle of James Bond, and where the series would go next. Enter Pierce Brosnan. In 1995, Goldeneye gave new life to the franchise and brought it back to its spy roots. While the Brosnan films, which include Goldeneye, Tomorrow Never Dies, Die Another Day, and The World is Not Enough, revel in peak '90s silliness — see Bond para-surfing a tidal wave in Die Another Day – they also introduced a whole new generation to James Bond.

However, none of the Brosnan films are based on any of Fleming's novels. That may have helped the franchise remain relevant to an audience that didn't recognize the tensions presented by the Cold War, when the novels are set, like their parents did. Brosnan's Bond goes after superpowered computer chips and satellites that can change the weather, rather than Soviet spies. These modern missions seamlessly integrated him into a popular culture that knew more about dial-up then it did about '60s world politics. Book fans might grumble, but that's part of what has kept Bond on the big screen.

Home again

2012's Skyfall is the highest-grossing Bond film to date. Upon its release, audiences were immediately and enthusiastically receptive to its blend of callbacks to series favorites, like the reintroduction of Q and the Aston Martin DB5, and its updated-for-the-21st-century computer-centric plot. Like the Brosnan films, none of Skyfall's story comes from Fleming's novels. Unlike the Brosnan films, however, Skyfall takes pleasure in blending '60s Bond beats with modern sensibilities.

Director Sam Mendes not only delivers exotic locations, Komodo dragon combat, and a series-standout villain in Javier Bardem's Silva, he also furthers the realistic and gritty aesthetic that characterizes the Daniel Craig Bond. Moreover, the film further develops Bond's character by delving into his backstory, while still making time for things like a headlight machine gun appearance. Skyfall signals to fans that the series has come home again, if in a slightly different form, and fans responded in kind. This is especially appropriate, because the only piece of the movie that comes from Fleming's work is the name of the film, which is also the name of Bond's childhood home.

Outside influences

Fleming's books aren't the only influence on the James Bond films — popular tropes and genres make their way into the franchise all the time. Sean Connery's Bond films stick close to Fleming's plots, with some changes and embellishments scattered here and there. However, when Roger Moore took over the franchise in 1973's Live and Let Die, Bond films began borrowing their aesthetic from popular genres and trends.

Live and Let Die is massively influenced by 1971's Shaft, 1972's Superfly, 1973's Trouble Man, and blaxploitation cinema in general. With its car chase in Harlem, fixation on voodoo, and the central villain's heroin smuggling, the movie wears its influences loudly on its sleeve. However, Live and Let Die ends up being an odd bit of blaxploitation in reverse. In the movie, Bond, a representation of the powerful establishment if ever there was one, is the hero — something very at odds with the genre the film borrows from.

Thus did Bond movies begin to reflect the changing views and interests of their audience. 1979's Moonraker – yes, the Bond movie featuring a space station battle between a nutty billionaire and the '70s equivalent of Space Force — came out just two years after Star Wars premiered. 1989's License to Kill sees Bond fight an international cocaine dealer, following the success of Scarface and Miami Vice. Thus, 007 stays hip — though today it's through a lot more computers and a lot less voodoo.

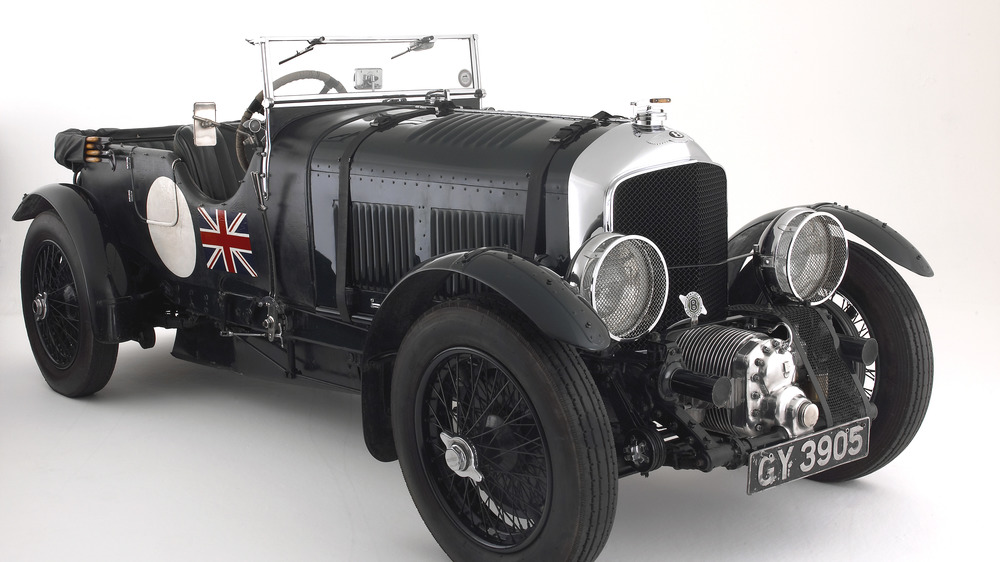

Bond's Bentley

Everybody knows the Bond cars. There's the submarine Lotus from The Spy Who Loved Me, the (mostly) BMW-heavy Brosnan years, the rocket-launching Aston Martin V12 Vanquish from Die Another Day, and, of course, the all-time iconic Aston Martin DB5, complete with ejector seats. While the DB5 is to Bond what the 1968 Mustang GT is to Steve McQueen's Bullitt, the original Bond of Fleming's novels actually drives a beloved Bentley. While a Bentley Mark IV does appear in 1963's From Russia with Love, it's not a book-accurate model.

When readers first meet Bond in Casino Royale, his ride of choice is, specifically, the 1931 4.5 Litre Blower Bentley. It's a classic British roadster, with a robust body and serious speed, relative to its time. Today, it has become a perfect metaphor for the transition Bond made from page to screen. On the page, Bond is all Blower Bentley: He's road ready, efficient, and a bit monstrous. On the screen, Connery established the character with a performance equivalent to a DB5: He's all class, until someone needs to be removed from the car via spring-loaded passenger seat.

Wedding day tragedy

With a new, one-time-only Bond performance from Australian George Lazenby and a byzantine SPECTRE plot involving bacteria-carrying sleeper agents, On Her Majesty's Secret Service is the black sheep of the Bond family. However, it does contain the first attempt to make Bond more sympathetic to his audience. In the movie, Bond romances and eventually — gasp! — marries Tracy Di Vincenzo. But the honeymoon is cut short when Bond's nemesis Blofeld kills Tracy in a drive-by shooting in Portugal.

The fact that a sentence that could describe a moment from The Godfather is the end of a Bond movie should explain why this was a step in a new direction for the franchise. It's a harrowing scene — it even ends with Bond cradling his lost love in tears — but it's also a blueprint for the steps the 2000s Bond would later take, to color in the man pulling the Walther PPK trigger.

A Q-worthy invention

Q, comedically portrayed as perpetually frustrated with 007 by the likes of Desmond Llewelyn and Monty Python member John Cleese, is always a shoe-in for fan favorite. The gadget scenes are a staple of the series, and whenever Q walks Bond through a deadly briefcase or a watch with a buzz saw, the audience knows it's getting its money's worth.

This is why Q serves as a great example of the upside of adaptational changes. In the Fleming novels, the Q branch is only mentioned — it was a stroke of genius by early franchise writers to turn Q in a full-fledged character with a dedicated appearance in most movies. Bond may flirt with secretary Moneypenny or subtly joke about his sexcapades with his boss, M, but when Q's on screen, Bond is treated like a schoolboy by the weary gadget master. The brief odd couple dynamic between the international man of mystery and his stern gadget clerk, who just wants his equipment returned in one piece, is a welcome dash of particularly British comedy, and a highlight of every film Q appears in.

A tragic end of tenure

1995's Goldeneye introduced audiences to Judi Dench's M. Dench arrives on scene and immediately puts Bond in his place, calling him a "sexist, misogynist dinosaur ... a relic of the Cold War." The scene not only adds some 1990s-style feminism to the series, but also redefines Bond's relationship with his superior. The 2000s Bond reboot films continue to flesh out this premise and make M both an active participant in the action and a surrogate parent to Bond.

Which — spoiler alert — is why her death at the end of Skyfall hits so hard. Dench's departure from the series is another great example of the power of adaptation: Fleming doesn't establish M's character as much as the films do, and Fleming never kills off the head of MI-6. However, the film's decision to do both makes the current incarnation of the 007 story stand apart from its predecessors. We miss you, ma'am.

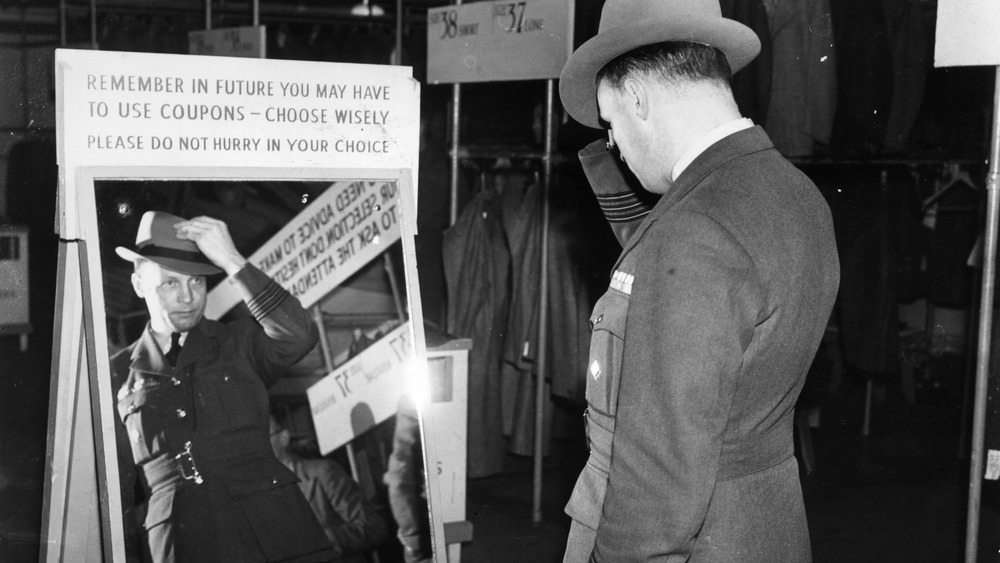

The real James Bond

With his constant sense of cool, anvil chin, and penchant for seducing beautiful women wherever he goes, Bond often registers as more of a fantasy than a full-fledged human being. However, there must be some truth to the character, because Fleming served in British Naval Intelligence during World War II, and reportedly based Bond's exploits on a contemporary named Forest Yeo-Thomas. The Telegraph's Jasper Copping explored the connection between Bond and Yeo-Thomas in a 2012 piece that reveals the truth about the man behind the myth — which, it turns out, is pretty spectacular on its own.

Copping details the parallels between 007 and Yeo-Thomas, which include a "tangled" love life, daring escapes from planes, trains, and camps, and notoriety for shooting first and asking questions later. While Yeo-Thomas, who was known by the Gestapo as "The White Rabbit," never thwarted a plot to cause a nuclear holocaust masterminded by a '70s sheik, his exploits are the stuff of legend. Yeo-Thomas escaped prison more than once, parachuted into occupied France, and persuaded Winston Churchill to lend more generous support to the French Resistance. It's amazing to think there's some fact behind what many consider to be the ultimate escapist fiction.

'60s camp sets the Bond standard

For viewers who've only seen the most recent run of Bond films, a deep dive into the series' archive might be shocking. In the Daniel Craig Bond films, the stakes are high, beloved characters can die, and no one is trying to found a master race by waiting out a global nerve gas attack in a custom space station filled with supermodels, a la Drax in Moonraker. The major difference between the films following Casino Royale and the rest of the series is camp. Until Daniel Craig's brooding agent came along, James Bond shamelessly dipped into the implausible — and sometimes, even the goofy.

Modern fans might balk, but some of the silliest features of the early Bond films — boombox bazookas, SPECTRE board meetings with death-trap furnishings — are the reason the films and the franchise are remembered so fondly today. Bond never shied away from going big, and even though the films' early plots invoke nuclear destruction when it was a highly-discussed possibility, characters with names like Pussy Galore kept the series firmly rooted in escapism. While Craig's turn as a battered and bruised man with a code reinvigorated the franchise for fans old and new, there's something special about Bond fighting a henchman named Jaws who kills with metal teeth. Camp gave Bond a license to entertain, no matter the cost. We'll raise a martini to that.