The End Of The Talented Mr. Ripley Explained

Thrillers, dramas, dark comedies, and character studies about queer people engaging in various forms of cons, deception, and other charismatic criminal activities have become especially popular in recent years. From social media hits like "Saltburn," "Do Revenge," and "I Care a Lot," to acclaimed indie and international flicks like "Kajillionaire," "Can You Ever Forgive Me?," and "The Handmaiden," it seems like the satirical countercultural motto of "Be gay, do crimes" has never been more cinematically en vogue than it is now. And one of the forebears of that wave was "The Talented Mr. Ripley."

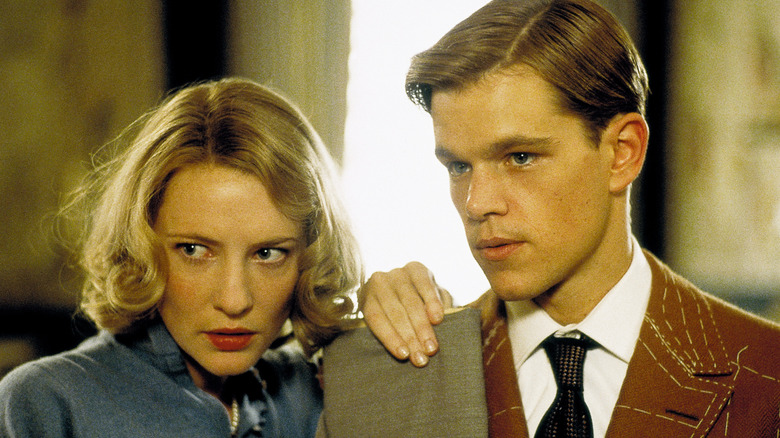

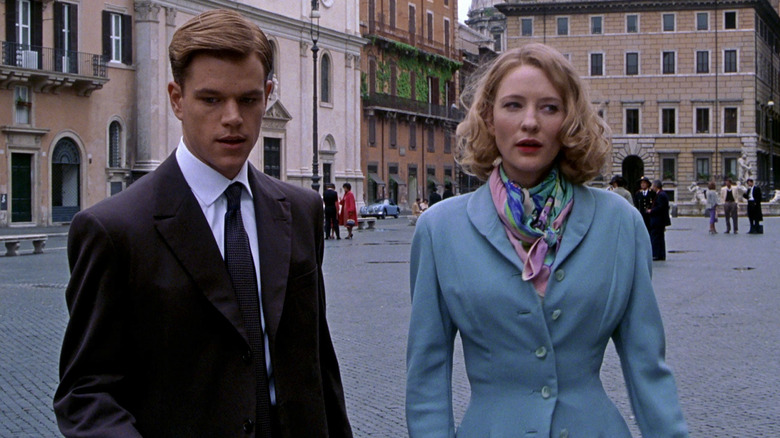

The 1999 Anthony Minghella film is remembered, of course, for introducing mainstream audiences to Jude Law, and arguably giving Matt Damon the role of his career. But it is also remembered for introducing a whole new generation to Tom Ripley, the most iconic creation of novelist Patricia Highsmith. Adapted from her 1955 novel of the same name, the film captivated audiences around the world with its vivid rendering of Highsmith's slippery queer con artist, constantly caught between crafty scheming and frantic despair amid a series of dazzling Italian seaside vistas.

To this day, it remains a cornerstone of all queer-criminal cinema — and its open, profoundly tragic ending remains a particularly fruitful discussion prompt among movie buffs. A significant deviation from the ending of Highsmith's novel, the denouement concocted by Minghella is fascinating to pick apart in terms of basic plot functionality, and even more so on a character level.

What you need to remember about the plot of The Talented Mr. Ripley

Set in 1958, "The Talented Mr. Ripley" follows working-class New Yorker Tom Ripley (Matt Damon), who's hired by shipping mogul Herbert Greenleaf (James Rebhorn) to travel to Mongibello, Italy. He's sent there to persuade Herbert's playboy son Dickie (Jude Law), whom Herbert mistakenly believes Ripley went to Princeton with, to abandon his blissful Mediterranean life and come back to the United States.

Dickie takes a shine to Ripley, sweeping him into his wealthy and carefree lifestyle; Ripley, in turn, becomes infatuated and obsessed with Dickie. Eventually, just as Herbert is giving up on his endeavor and cutting off Ripley's travel funds, Dickie grows weary of his new friend. On their final trip together to Sanremo before parting ways, they have a heated argument aboard a two-person boat, which culminates in Ripley murdering Dickie.

Ripley sinks the boat with Dickie's body in it, and — making use of his uncanny skills for forgery and impersonation — assumes Dickie's identity, convincing his long-suffering girlfriend Marge Sherwood (Gwyneth Paltrow) that he has left her and moved to Rome. While living off Dickie's allowance in Rome, Ripley draws the attention of Dickie's fellow rich friend Freddie Miles (Philip Seymour Hoffman), who shows up at "Dickie's" new house demanding answers. Once there, Freddie finds out the truth — prompting Ripley to kill him, dispose of the body, and enter into a cat-and-mouse game with Rome police officers, who believe him to be Dickie.

What happens at the end of the film?

As the investigation closes in on "Dickie," he's forced to abandon his new identity and become Ripley again. He forges a suicide note from Dickie that owns up to Freddie's murder, then slithers away to Venice in the middle of the night, where he becomes reacquainted with Margo and her friend Peter Smith-Kingsley (Jack Davenport). He's almost caught when Marge finds Dickie's rings in his possession, and then again when law enforcement from Rome arrives in Venice to interview him about his relationship with Dickie, but manages to evade incrimination by the skin of his teeth each time.

Finally, Herbert arrives in Venice with private detective Alvin MacCarron (Philip Baker Hall), who informs Ripley that the Italian police are convinced Dickie killed Freddie and then committed suicide. Even after uncovering that Ripley never went to Princeton, it never occurs to MacCarron or Herbert that he could have killed Dickie, despite Margo's furious insistence that he did. As if that weren't enough of a freebie, Herbert then bequeaths a significant amount of Dickie's trust fund to Ripley, believing that's what his son wanted.

Somehow, it seems like Ripley is in the clear after everything he's done. He then boards a cruise ship to Greece with Peter, with whom he has become close. Aboard the ship, however, Ripley runs into the only remaining loose end: Meredith Logue (Cate Blanchett), an unsuspecting American socialite with whom he had a brief tryst as Dickie.

Why does Ripley kill Peter instead of Meredith?

Once Ripley runs into Meredith on the boat, forcing him to assume his old Dickie persona, he learns that she's there with her whole family. Once again, Ripley overplays his hand and gives Meredith a tender kiss — perhaps imagining that's what Dickie would do. This time, the consequence is immediate: Peter has quietly witnessed the kiss, knows Meredith, and wants to know what the heck is going on.

We know by that point that Ripley isn't above killing people to throw off his scent; just a few scenes ago, he was on the verge of murdering Marge with a razor blade after she found Dickie's rings. Even so, why does he kill Peter, the first person in his life to have ever shown him true love, instead of Meredith, who has never known him as Ripley and means nothing to him?

On a plot level, of course, the answer is that killing Meredith would be unworkable. Her whole family is there, they saw him with Ripley, and they're unlikely to leave her alone and unseen for long. Peter, meanwhile, is all alone with Ripley; he saw Meredith aboard the boat, but she didn't see him. No one will miss him, and Ripley will have plenty of time to escape by the time his body is found. It's a no-brainer, logically speaking. Emotionally, meanwhile, it paints Ripley as exactly what he is: a resourceful, unscrupulous, yet deeply tortured hustler.

What is the nature of Ripley and Peter's relationship?

The great irony of the film's ending is that, after getting himself into the ruse of the century out of his sheer unreciprocated obsession with Dickie Greenleaf, Tom Ripley suddenly finds himself in a genuinely loving, caring, and understanding romantic relationship — in other words, his greatest fear.

Throughout the whole film, Ripley has repeatedly pretended to be someone else, in a constant effort to meet people's expectations and ingratiate himself with them. He does it because, as he reveals to Peter, he has a deep-seated fear that anyone who truly knew him — who truly saw the darkness of his soul and past deeds — would be horrified and turn away.

On some level, of course, he's still performing for Peter by the time they've fallen in love and gone on a romantic trip to Greece together. But it's clear from their interactions that Peter is the one person with whom Ripley feels remotely comfortable being himself. He may keep a wall around his dark secrets, but Peter accepts and gets to love Ripley for who he is now. The tenderness and simplicity of their budding relationship in the film's last third makes for a sharp contrast with the intense, performative, brittle connection between Ripley and Dickie. As viewers accustomed to that raucous rhythm, we almost don't notice it when Ripley and Peter are becoming an item — which is very much intentional.

How did Ripley manage to get away with it?

Before Meredith's appearance jeopardizes Ripley's entire plan, forcing him to murder the one person who loves him, he actually gets a taste of impunity — an impunity that he could have easily maintained if he'd simply managed to avoid Meredith. How do things almost work out so completely in his favor even after everything he's done?

The answer is a combination of factors, some carefully leveraged by Ripley, some fortuitous. His ability to identically forge signatures and handwriting makes it impossible for the police to catch on to the fact that it wasn't Dickie himself drawing from his bank account. His scratching off of Dickie's picture on his ID — interpreted by Herbert as a sign of Dickie's mental instability prior to (supposedly) killing himself — ensures that Rome police will likely never know Ripley doesn't look like the real Dickie. Dickie's history of violence and irresponsible behavior — including his affair with Silvania (Stefania Rocca) that ends with her getting pregnant and committing suicide — makes it easy for the police to believe that he could have murdered Freddie and then killed himself in a guilty stupor.

Most importantly of all, the Greenleaf family's eagerness to sweep their son's troubled history and possible crimes under the rug supersedes whatever suspicion they might have about Ripley. At the film's end, the Greenleafs are also behaving like cornered animals intent on evading capture, which makes it impossible for them to consider that a different, true culprit might be out there in the same situation.

What the ending of the film says about Tom Ripley

Why, after almost having his deception exposed, does Tom Ripley make the decision to keep parading around Europe as though there were no menace at all hanging over his head? Why isn't his instinct to lie low and wait for the dust to settle, or else travel as discreetly as possible to make sure he'll never run into Meredith or any other liabilities?

The answer, simply put, is that Ripley is not a machine. Even as he perfectly calibrates his behavior and calculates his every move to ensure his plans' success, a part of him can't help giving in to a desire for something discordant. Just look at his completely senseless decision to hang on to Dickie's rings — which very nearly ruins him — rather than simply dispose of them. More than that, consider his momentary decision to invite Marge into "Dickie's" apartment and confess everything; consider his immense relief at the idea before coming into his senses.

For all his suaveness, Ripley's game is killing him; something in him wants to get it all over with, to get caught, to stop living a lie. Even the guilt-free part of him still longs to live a "normal" life, and insists upon it as if it were possible, refusing to make any concessions or change any plans; on some level, it's like he's testing the limits of the lucky break the world has given him, assessing just how much freedom and impunity it actually affords him.

The film ends differently from the novel

Although the bulk of Anthony Minghella's "The Talented Mr. Ripley," including most of the film's denouement, tracks closely to the Patricia Highsmith novel, there is a significant difference in the way that the film ends. In the novel, following Ripley's visitation with the private detective in Venice, he travels to Greece alone, convinced that he will inevitably get caught at some point. It's only then that he learns the Greenleafs have accepted the police's theory and bequeathed part of Dickie's inheritance to him. The novel ends with Ripley seemingly free from any and all consequences, at least for the foreseeable future.

Even so, when we leave the novel's Ripley, he's consumed by paranoia, wondering upon every arrival to every pier if maybe this is the day in which he'll finally be accosted by police officers and exposed as a murderer. In other words, although the film's ending is significantly more tragic and more legally cumbersome for Ripley, it reaches the same conclusion: No matter how well things shake out for him, he'll never truly be able to outrun what he did. The weight of his actions is too great to be simply shrugged off; whether in the form of constant anxiety (as in the novel) or concrete material threats to his impunity (as in the film), Dickie, Freddie, and Peter's murders will always come back to haunt him and soil his seemingly perfect new life.

The final scene is deeply significant

In the very last scene of "The Talented Mr. Ripley," Anthony Minghella crucially cuts away from the image of Ripley killing Peter, leaving only the sound of their final interaction. We watch Ripley return to his own room, sit on the bed, and stare blankly into nothing, while merely hearing the noise of Peter choking as Ripley wails in despair at what he's doing.

On the most basic level, that directorial decision evinces Ripley's increasing sense of dissociation from himself and his life. Then there's the irony of hearing the sound of the murder — the sound of an unsuspecting Peter verbally doting on Ripley, cooing "Tom has someone to love him," only to be brutally assaulted — over a moment of deep physical loneliness for Ripley, who processes what just happened while sitting all alone in his room. What that aural superimposition shows is that, in that moment, that gruesome episode is being sublimated in real time into a memory. And that memory ironically epitomizes both Peter's love for him, and his deep capacity for acts he himself considers evil.

Visually, the last couple of shots are key as well: Ripley is surrounded by mirrors that refract him into various different images of himself, yet his expression remains perfectly blank, emotionless, inaccessible. Tom Ripley has now played one too many characters; his nesting performances have transformed him into a shell of a person, devoid of anything but the intricate appearances he's sacrificed everything to maintain.

Tom Ripley is not your standard movie psychopath

If the film's last scene doesn't exactly solve the mystery of who Tom is and what makes him tick, it does clarify why poring over that mystery has proven so compelling.

Even though Ripley has murdered three people by the end of the film, he still doesn't come off as a standard movie psychopath. In fact, we end the movie unsure if he can even be said to be a psychopath at all. While killing Peter, he can't help sobbing, apologizing, and screaming his lover's name. Yet he still does it, and an attentive watch of the scene reveals that he's already discreetly reaching for his scarf as soon as Peter reveals that he saw the kiss. Ripley is at once deeply calculating and deeply disturbed — even disgusted — by his actions; he feels immense remorse and shame, but doesn't let that stop him.

His entire characterization is predicated on that kind of dichotomy; he's smooth yet awkward, arrogant yet insecure, admiring yet contemptuous. He plans carefully and follows through on his plans, yet always seems to be bumbling through them. In short, whether or not he's a psychopath, whether or not he's evil, he's profoundly human — a walking contradiction of a protagonist who we love watching both for his wins and for his failures. We may not know for sure who he is — each viewer will have a different answer — but we're irresistibly driven to try and find out.

Meredith's role in the denouement is deeply ironic

The character of Meredith Logue was specifically invented for the film by Anthony Minghella. As a matter of fact, she plays a crucial role in Minghella's personal vision for the story, and this is demonstrated by his choice to have Meredith — rather than any character from the novel — be the person responsible for causing Ripley's seeming victory to unravel.

Throughout the whole film, Meredith is the only major character who's kept entirely on the outside by Tom Ripley — the only person who knows him as Dickie Greenleaf with whom he forms a meaningful personal connection. Ripley believes that, by keeping Meredith entirely separate from and oblivious to his actual existence as Tom Ripley, he will be able to control their relationship to whatever extent he desires. He sees Meredith almost as a cipher, a mere character in a fiction of his own making, definitionally incapable of affecting his "real" life.

But it is Meredith's very separation from Tom Ripley's life as himself that makes it impossible for him to bend her to his will as he does everyone else. Ripley believes that he's at his most masterful and manipulative when playing Dickie Greenleaf, but it is in fact the character of Tom Ripley — the poor, shy, downtrodden, woe-is-me outsider — that he's able to really, consistently deploy in his own favor. Meredith has never met that character, so she's the only one who ultimately doesn't fall in line with his plans.

What will happen to Ripley after the end of the film?

It's likely that, since no one aboard the boat will miss Peter, Ripley has hidden the body somewhere, and will simply get off and flee the scene at the next pier. Even if he does, however, Peter's body will eventually be found. And then what? The police could still somehow fail to trace him back to Ripley, of course. But this will be the third mysterious death of someone in his social circle; at what point do suspicions become inevitable? Even if we assume that he's just buying time, and will try to disappear into the world before the police can even find him, was that really worth murdering the only man who ever loved him?

None of these questions have answers, alas. Although there have been film adaptations of Highsmith's subsequent Ripley novels, they aren't connected to the Minghella film — which ends differently from the novel anyway. The film's story is a one-and-done. But the mere fact that there remain so many questions is what makes that ending so powerful. There's a non-negligible possibility that Ripley's ultimate act of spiritual self-destruction will eventually be all for naught — but there's also a possibility that it was useful, and that it will allow him to get away once again. It's not so much a question of which will turn out to be the case, but which is worse. We don't know, and, judging by those closing blank stares, neither does Ripley.