What You Need To Know About The Lord Of The Rings Spinoff

The Lord of the Rings is a big deal. J.R.R. Tolkien's epic fantasy created a genre, inspired three hit movies, and singlehandedly altered the economy of New Zealand. So you can imagine the excitement when HarperCollins announced that Tolkien's spinoff story about lovers Beren and Lúthien was to be published as a standalone novel in 2017 — exactly a century after Tolkien started writing it.

Beren and Lúthien is one of J. R. R. Tolkien's best stories. It's also not an easy read. Oh, sure, there's a lot of good stuff tucked into its 250-plus pages, but in order to find it you'll have to wade through a mishmash of different writing styles, numerous editorial notes, and a whole mountain's worth of Middle-earth lore.

In other words, Beren and Lúthien is not a straightforward adventure story like The Lord of the Rings, and if you approach it like one you'll be severely disappointed. That doesn't mean it's not worth reading — you just need to be prepared. What follows is everything that you need to know to enjoy one of Tolkien's biggest, most exciting, and most intimate tales. Read on, and you should be well-prepared for anything your journey through Beren and Lúthien throws your way.

It's J.R.R. Tolkien's most personal story

Beren and Lúthien is a dense and complex text, but if you take out all of the references to Middle-earth's history and sort through Tolkien's archaic language (more on that later), you'll find a simple love story lurking underneath. Beren, a mortal man, falls in love with a beautiful elf maiden named Lúthien. Lúthien's father disapproves and forces Beren to go on a suicide mission in order to prove his devotion. He does.

While John Ronald Reuel Tolkien Tolkien didn't fight monsters to win the hand of his beloved, Beren and Lúthien clearly draws on Tolkien's real-life relationship with his wife. Young Ronald met his future bride, a fellow orphan named Edith Bratt, when he was just 16. Tolkien's guardian, however, thought Edith was distracting Ronald from his schoolwork, and forbid Tolkien from corresponding with the woman until he turned 21.

Remarkably, Tolkien waited. As soon as his 21st birthday arrived, Tolkien wrote to Edith and proposed. They married three years later. Tolkien said he never actually called Edith Lúthien, but admitted that the character is based on her — he came up with Beren and Lúthien in 1916 after watching Edith dance in a grove of hemlock trees.

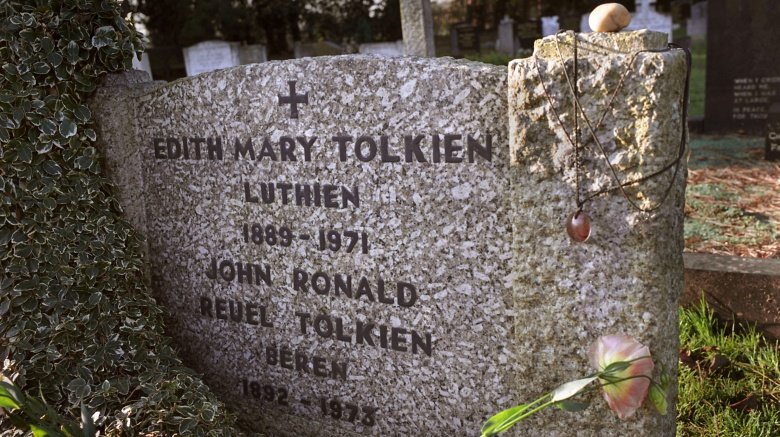

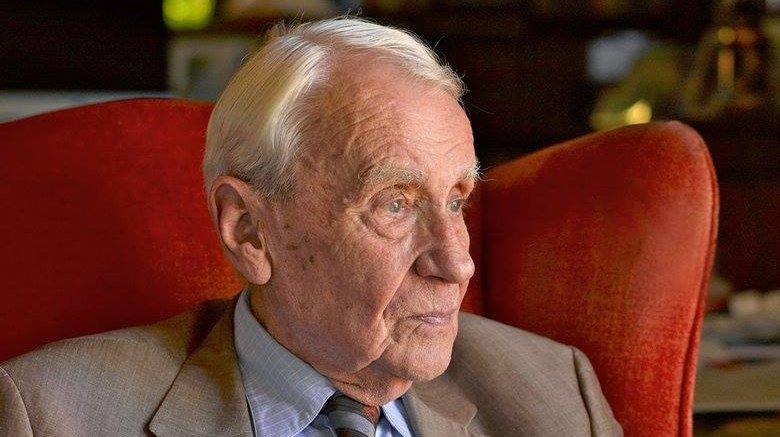

Tolkien's love for Edith never faded, and their shared tombstone contains the names Beren and Lúthien, which were added at Tolkien's request. The personal connection is why Christopher Tolkien, J. R. R.'s son, decided to close out his decades-long career of preserving his dad's work by publishing this story. "In my ninety-third year this is (presumptively) my last book in the long series of editions of my father's writings," Christopher writes in Beren and Lúthien's preface. "This tale is chosen in memoriam because of its deeply-rooted presence in his life."

It's a prequel

If you're looking to catch up with Gandalf, Aragorn, Bilbo, Gollum, Legolas, and the rest of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings crew, you won't find any of them here. The War of the Ring takes place in Middle-earth's Third Age. Beren and Lúthien is set during the First Age, a full 5,568 years before Frodo travelled to Mount Doom.

During this time period, hobbits don't exist yet, and the One Ring won't be forged for over a thousand years. In fact, the only familiar face that pops up during Beren and Lúthien is Sauron, The Lord of the Rings' big bad, and at that time he's going by the name Thû.

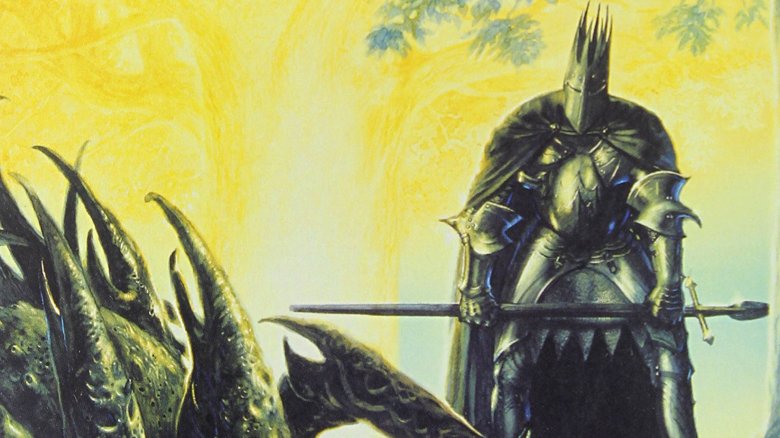

He's not the all-powerful force that you remember, either. In the First Age, Sauron was a lackey of Morgoth, the most powerful of the Ainur (i.e. Middle-earth's second most-powerful tier of gods), and the first living being made by the world's all-powerful creator, Ilúvatar. If you think Sauron is bad, Morgoth is infinitely worse. He made the orcs by capturing and torturing elves, and he destroyed the gods' magical Two Trees, which provided the world with light before the sun was created.

Other than Sauron and Elrond, who appears at the very end of Beren and Lúthien (Beren and Lúthien are Elrond's great-grandparents), the cast is all new (Galadriel is alive during the story, but doesn't appear). So is the location where all the action happens. Beleriand, where Beren and Lúthien takes place, doesn't exist by the time The Lord of the Rings rolls around. It was flooded and destroyed when the other gods stepped in and took care of Morgoth for good, ending Middle-earth's First Age.

Beren and Luthien isn't a complete text

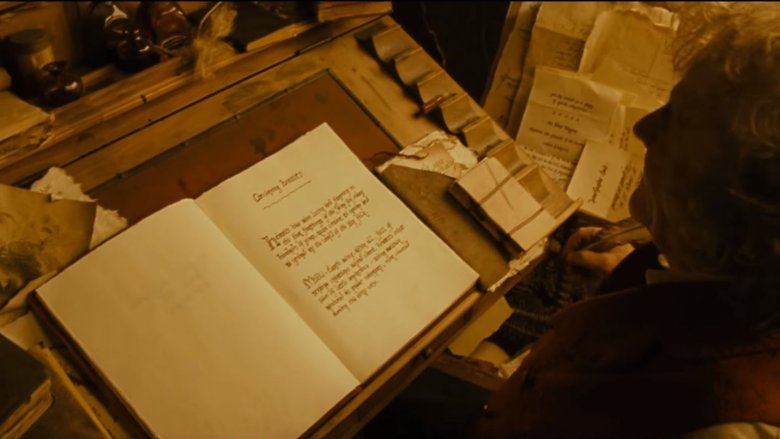

J. R. R. Tolkien was a notoriously fiddly writer — he revised The Hobbit 17 years after publication to make it sync better with The Lord of the Rings — and as a result, the history of Middle-earth changed constantly over his lifetime. He also had a hard time finishing things. While Tolkien spent his whole adult lifetime creating Middle-earth's mythology, The Silmarillion didn't come out until after his death, when his son Christopher pieced together a book from a number of different sources.

As a result, there isn't really a complete version of Beren and Lúthien, and the new book is a patchwork made up of pieces of different texts. It starts with a very early version of the story called "The Tale of Tinúviel" that trades Sauron for Tevildo, the Prince of Cats (and which, in a subplot, explains why dogs and cats hate each other). The more modern version of the story, which contains more ties to Middle-earth's broader history, is stitched together from the Qenta Noldorinwa (a condensed summary of Tolkien's overall mythology), an unfinished piece of epic poetry called The Lay of Leithian, and a couple of other sources.

Stylistically, The Qenta Noldorinwa and The Lay of Leithian don't go together at all, making for a very choppy and disorienting read. Thankfully, editor Christopher Tolkien provides plenty of notes and summaries to keep you oriented — after all, if anyone knows Middle-earth, it's him. When Christopher was a teen, Tolkien paid him two pence for every continuity error he found in The Hobbit. From the '70s onward, Christopher dedicated his life to documenting, editing, and publishing his father's writings.

By the way: if you're already a Tolkien expert, there's no new material here. If you've already read The Silmarillion and Christopher Tolkien's History of Middle-earth series, then you've seen everything that Beren and Lúthien has to offer. You just haven't seen it presented like this.

The Silmarils are the OG One Ring

In order to win Lúthien's hand in marriage, Beren has to bring her dad one of the three Silmarils embedded in Morgoth's crown. That's kind of like asking someone to travel to Hell and steal the devil's pitchfork, but Beren likes Lúthien a lot, so he agrees anyway. But what is a Silmaril, and why does everyone want one?

To understand, we need to leave Middle-earth and head west to Valinor, where the gods lived alongside a number of elves (y'know, where Frodo, Bilbo, and Gandalf were headed on that ship at the end of The Return of the King). Way, way back in the day, Valinor had two trees. One was silver, one was gold, and together they provided all the light for both Valinor and Middle-earth. One day, an extremely talented elf named Fëanor created a set of three jewels that contained actual light from those trees. These were called the Silmarils, and their beauty made them very, very popular. Even Morgoth wasn't immune to their charms.

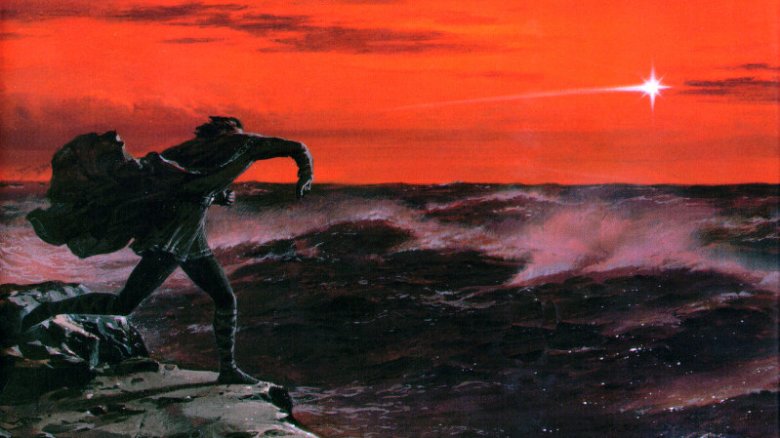

With help from a giant spider named Ungoliant (you might remember her daughter, Shelob, from the book The Two Towers and the movie The Return of the King), Morgoth attacked Valinor, stole the Silmarils, and destroyed the two trees, plunging Valinor into darkness. Then, he fled to Middle-earth and put the Silmarils in his crown. As you can imagine, Fëanor wasn't happy about Morgoth stealing his stuff — but we'll get to that in a minute.

Unlike the One Ring, the Silmarils don't have any real power (although they'll burn any mortal or evil creature who touches them), but since they contain the last remnants of the Two Trees' light, they're extremely valuable. Like the One Ring, the Silmarils are the objects everyone wants, and the struggle to control them is the source of numerous conflicts over the years.

The elves can be real jerks

The Lord of the Rings movies depict the elves as either noble warriors or mysterious wise men (and women), but actually, they're just people. They might be immortal, but in Tolkien's writings, the elves can still be as jealous, angry, short-sighted, and vindictive as the rest of us.

Naturally, when Morgoth steals the Silmarils, Fëanor (who's already a self-centered hothead) is pissed. Fëanor swears an oath that he and his seven sons will hunt down anyone who holds a Silmaril and keeps it from his family, and heads to Middle-earth to get the jewels back. If The Silmarillion has a main plot, it's Fëanor's family's quest to reclaim the Silmarils and the trouble that it causes (spoiler: it doesn't go well), and while Fëanor is dead by the time Beren and Lúthien takes place, two of his kids play small but important roles in their story.

When the elvish king Finrod abdicates his throne in order to help Beren steal a Silmaril, two of Fëanor's sons, Celegorm and Curufin, take over Finrod's kingdom in revenge. Beren and Lúthien doesn't do a great job of explaining why Celegorm and Curufin are so angry, but it all comes back to that oath. Celegorm and Curufin think the Silmarils are theirs, and don't take kindly to Beren and Finrod going after their personal property. Celegorm and Curufin function as secondary antagonists throughout Beren and Lúthien, and Celegorm's dog, Huan, ends up being pretty important as well.

The language can be difficult

Tolkien is best known as a fantasy author, but writing was really just his hobby. He was a trained linguist who contributed to the Oxford English Dictionary (allegedly, he worked on the w's) and enjoyed a long tenure as a Professor of Anglo-Saxon at Oxford University. As a result, Tolkien's poetry often mimics the structure and cadence of Old Norse epics, which can be daunting to new readers, and he often relies on antiquated or obsolete definitions of words.

When Tolkien talks about "gnomes," for example, Tolkien's actually referring to a subset of particularly knowledgeable elves — the word "gnome" is similar to "gnosis," the Greek word for "wisdom" — and not bearded creatures with pointy hats. "Fairies" are just elves, too. Tolkien's use of the term "fey," which applies to Lúthien's mom, is a little more complicated, but he's basically referring to the powerful spirits in his mythology known as the Maia (Gandalf, Saruman, and the Balrog are Maiar, too).

Of course, many of the words in Beren and Lúthien are made up. Tolkien created a number of fictional languages, and only started writing stories because he needed people to speak them. That means that names change across drafts as both the languages and the stories evolve. In "The Tale of Tinúviel," Morgoth is called Melko, and Tinúviel (elvish for "Nightingale") is another name for Lúthien.

This all might sound overwhelming, but, thankfully, Christopher Tolkien included both a glossary and also a guide to names in Beren and Lúthien. If you don't know what "opes" or "spoor" means, don't panic. There answers are waiting in Beren and Lúthien's backmatter.

Luthien is Tolkien's most badass heroine

Women don't get much play in Peter Jackson's The Lord of the Rings movies, and it's even worse in the books. Eowyn, who and squares off against the king of the Ringwraiths, is pretty darn cool, but she also spends a lot of time pining after Aragorn. We know Galadriel has power, but we only get a glimpse of what she's capable of. Arwen, Aragorn's girlfriend, spends all three novels almost entirely off-screen, and the bulk of her story is relegated to The Lord of the Rings' dense appendices.

By contrast, Lúthien is front and center throughout Beren and Luthien. In the story, Lúthien is cunning, loyal, and exceptionally brave, and she doesn't have any qualms about facing down rogue elves, werewolves, Morgoth, and the god of death himself. When Beren gets in trouble (something he does a lot) she rushes to his rescue, and when he tries to send her home and away from danger, she stays defiantly by his side.

It's not a perfect representation, of course. Lúthien's unfathomable beauty is one of her most defining traits, and everyone from Fëanor's sons to Morgoth seems to have the hots for her. At times, she's treated more like a prize and less like a person. Still, if you're tired of seeing Middle-earth's men hog all the glory, Beren and Lúthien is a refreshing change of pace. At the end of the day, she's the story's real hero.

In Middle-earth, music is magic

Lúthien doesn't use weapons in her battles against the forces of darkness. She uses magic. For The Lord of the Rings fans, that can be jarring. While Frodo's story is full of bizarre creatures, enchanted artifacts, and prophecies, examples of actual spellcasting are relatively hard to find. Beren and Lúthien, meanwhile, is full of magic. From shapeshifting to spell-induced hair growth, almost nothing is off the table.

In Beren and Lúthien, Lúthien emerges as the story's main magician, although Finrod gets a moment to shine too. In both cases, magic is directly tied to song and dance. That might feel random, but it's actually an ongoing theme throughout Tolkien's work. In fact, the link between magic and music goes all the way back to the very beginning. When Ilúvatar created the Ainur, the first thing he did was teach them music. Their various harmonies came together and helped create the world (Morgoth, naturally, sang his own tune, which Tolkien describes as "loud, and vain, and endlessly repeated," and says was intended to "drown the other music by the violence of its voice").

Beren and Luthien is key to Aragorn and Arwen's story

Beren and Lúthien does have one big link to The Lord of the Rings: Beren and Lúthien's story provides the backstory for Aragorn and Arwen's romance, especially Arwen's biggest and most important sacrifice.

See, not only did Beren and Lúthien break social boundaries by becoming one of Middle-earth's few human-elf couples, but their love for each other was so strong that the gods gave Lúthien a choice: she could either move to Valinor and live forever, as all elves end up doing, or she could renounce her immortality and live out the rest of her natural life with Beren, her main squeeze. Because Beren and Lúthien's kids have mixed heritage, that decision applies to each one of them and all of their future descendants.

Elrond, Beren and Lúthien's great-grandson, chooses to remain immortal, as do most of Beren and Lúthien's line. Elrond's daughter, Arwen, faces a harder decision. Like Lúthien, she's in love with a mortal man. Now, Aragorn lives for a long, long time — according to The Lord of the Rings' appendices, he dies at a modest 210 years old — but that's a drop in the bucket compared to forever. Ultimately, Arwen chooses love over everlasting life, proving that she takes after her great-great-grandmother in more ways than one.