Why 12 Monkeys Is Terry Gilliam's Best Film

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

The phrase "directed by Terry Gilliam" instantly lets you know what kind of movie you're getting into. His surreal visions, seen even before his film career began in the interstitial cartoons he created for Monty Python's Flying Circus, imagine dead-eyed bureaucrats, brilliant heroes revealed to be feckless and stupid, and commoners stretched into garish totems, giving their lives away in envy of those same bureaucrats and heroes. Gilliam's movies are darkly comic and filled with claustrophobic framing captured in tense Dutch angles. Should a deus ex machina come into play, it arrives as the foot of God, appearing from heaven to squash you.

Even knowing all of this long before a second of footage has rolled, Gilliam's 1995 movie, 12 Monkeys, still has the ability to shock and stun. Even today, fans debate its peculiar last-second plot twist, which examines the viewer's psychology as much as its own story. All these elements and many more confirm that 12 Monkeys is Terry Gilliam's best film. Still need convincing? Read on for the proof.

Dystopias and time travel

Why are people drawn to dystopias? Well, dystopian futures depict how bad things could be, versus how bad things are in the present. In this, dystopian stories offer comfort: Things are terrible now, but they could be infinitely worse. Time-travel stories are similarly popular as escapist "grass is greener" parables. 12 Monkeys merges these two staples of science fiction to tell a potent story about obsession and possibility. Jeffrey Goines believes corporate powers like his father have built a metaphorical cage around humanity. Dr. Peters believes the Earth is a self-regulating system, which humanity threatens to destabilize. These dystopian visions are harrowing, but remain abstract and exaggerated enough that the viewer can say, "Things are bad, but not as bad as that."

As for time travel, James Cole's journey through time similarly compares the flaws of the present to the miseries of other eras. It also tells a story about man's hubris, and the eternal struggle for self-definition and change. For all its convolution, Cole's journey ultimately takes him to the airport, where he witnesses his own death. His future is written for him by unseen hands, and will continually knock him back onto a path that is beyond his control. His free will is, in short, a total illusion. In blending two sci-fi concepts to examine just how bad things can get and just how small we really are, Gilliam offers a fresh take on thought-provoking ideas.

Inspired by film history

12 Monkeys was inspired by Chris Marker's 1962 short film, La Jetée. It tells the story of a survivor of World War III who is sent through time to stop the crisis. He too has visions of a child witnessing a man's death. By the end, he thinks he has succeeded ... until he sees the child and knows he has walked right into his worst visions.

12 Monkeys fills in the open spaces of this story with commentary about capitalism, environmentalism, masochism, and extremism. Gilliam's departures from La Jetée are intriguing: Jeffrey Goines may look and act like the most obvious suspect, but the crime at the movie's core is actually committed by Dr. Peters, a scientist who has rationalized genocide as a moral good. It all comes down to the arrogance of the few making terrible decisions for the many.

12 Monkeys is far more kinetic than La Jetée, as one would expect from Gilliam. Nonetheless, the premise is consistent across the two presentations. The key element of 12 Monkeys' success, however, is that it never gets ham-fisted. All of these heady ideas run wild just below the surface, while the relationship between Cole and Dr. Railly drives the story to its fateful conclusion. The audience doesn't have time to think too hard about the philosophies being tossed around in the film until after it's over.

A tight script anchors 12 Monkeys' big ideas

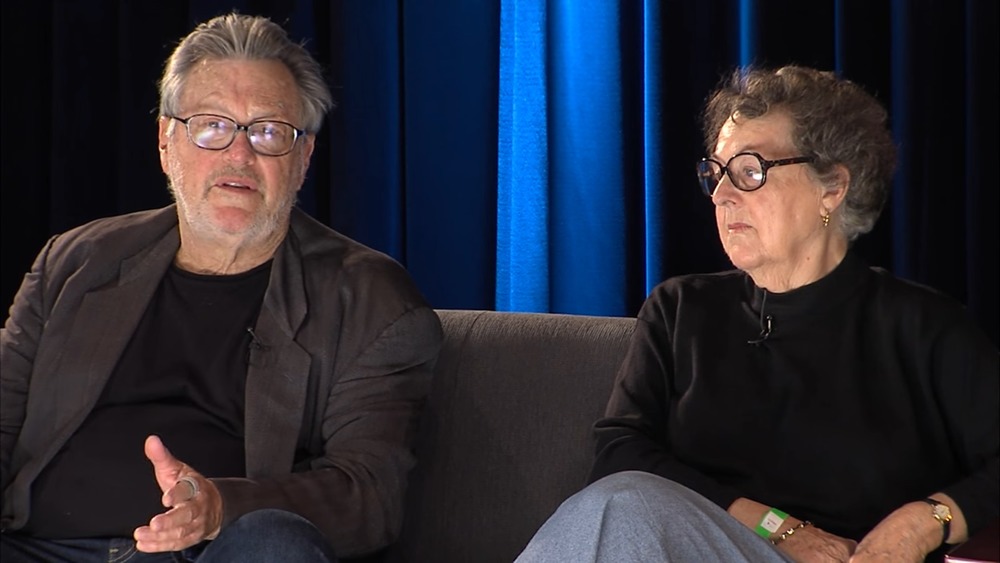

One of the primary reasons why 12 Monkeys works is its tight script. As James Cole is flip-flopped through time and space, he gets ever-closer to the moment of his paradoxical death. To pull that sort of climax off, you need to be sure all plot threads are at least addressed, if not conclusively answered. Screenwriting husband and wife team David and Janet Peoples managed to do just that.

Janet Peoples has only one pre-12 Monkeys writing credit, on the 1980 documentary The Day After Trinity. Taken by volume, David Peoples is not prolific either, but has made the most of his scripts that have gone to production. He came to public attention for his work on Blade Runner, following up script writer Hampton Fancher. He also wrote the screenplay for Clint Eastwood's Unforgiven, co-wrote the 1989 underwater monster flick Leviathan, and was prepped for an aborted adaptation of the 1960s cult classic television show The Prisoner for Christopher Nolan.

In 12 Monkeys, the Peoples keep the protagonists from feeling like props being battered by cruel fate. Although the audience knows subconsciously the relationship between Cole and Railly is doomed, the script manages to put the collective audience in a state of denial long enough to forget the inevitability of the third act. That takes serious skill.

Settings matter

12 Monkeys doesn't just feature a disturbing vision of the future, but also the seldom seen on-screen locations of Philadelphia and Baltimore. This decision amps up the feeling of anxiety, because a large number of viewers aren't familiar with these settings. Typically, there are three big cities represented in Hollywood films: New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago. Most people don't live in those places either, but they're filmed so often, they've become familiar.

Giving Philadelphia and Baltimore pride-of-place, in contrast, has multiple benefits. The age and architecture of these cities is balanced nicely with the film's ragged, almost steampunk-esque rendition of the future. That far-off era is dark, dripping, and hotwired together with cast-off technology. 12 Monkeys strengthens its messages by highlighting the differences between these settings.

The unfamiliarity of these cities to the majority of viewers also allows the storyline of the present to blend well with that of the future. Viewers know what New York and LA look like (even when they're actually Vancouver), but they're not as comfortable with Baltimore. Combined with a well-designed color palette, 12 Monkeys thus maintains visual consistency between the present and the future. This unique variety of scenery gave Terry Gilliam a chance to create a look both foreign and grounded at the same time.

Gilliam's demands were met

12 Monkeys successfully puts director Terry Gilliam's absurdist tendencies towards creating a twisted allegory denouncing man's hubris. Uniquely, the screenplay was already written: Gilliam had no influence on that process. He was a director-for-hire.

Even so, he had conditions that had to be met for him to make the picture. The film was to be a Universal Pictures production, and Gilliam's notorious 1985 fight with studio head Sid Sheinberg is legendary. Universal would not release Brazil until Gilliam made changes. Instead, Gilliam waged a public campaign against Universal, buying ads challenging Sheinberg to release the movie. If he was to make 12 Monkeys for the studio, he would have to have "final cut," meaning his vision would be maintained, and no studio interference would occur after final edit was "locked." Universal agreed, provided Gilliam deliver the movie at no stronger than an R rating, and no longer than two hours and 15 minutes in length.

This meant there were no incongruous happy endings tacked onto the film, the grit and grime of the set pieces remained in place, and the underlying anti-corporate tangents were not softened to assuage itchy investors. This is, in every sense, a Terry Gilliam film — and thank goodness for that.

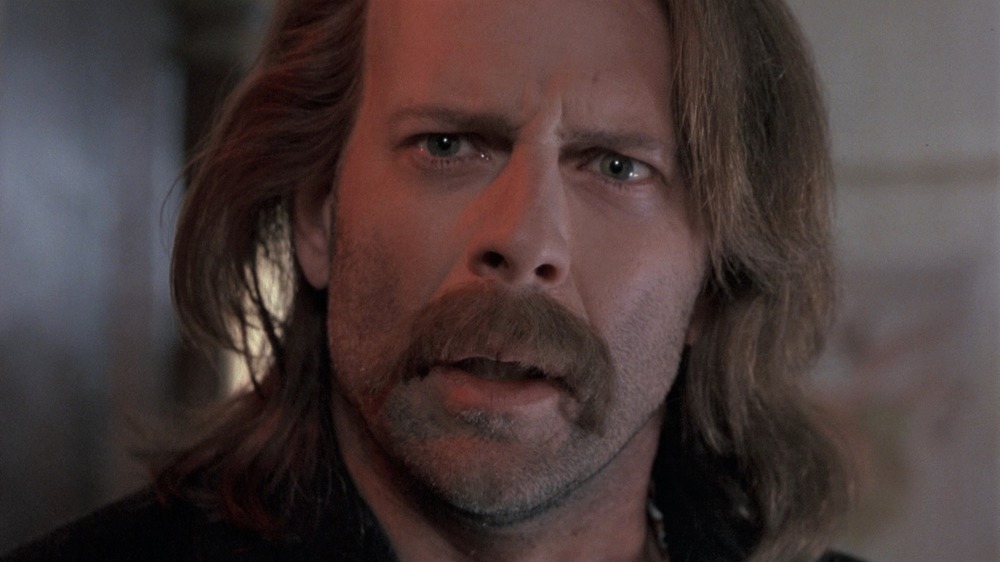

Bruce Willis stands out

To ensure he wouldn't miss out on the role of James Cole, Bruce Willis took a drastic pay cut – that's how badly he wanted to work with Terry Gilliam. Prior to 12 Monkeys, Willis was still getting roles that leaned on the smirking charm of Die Hard's John McClane, or his portrayal of David Addison, the goofball detective from the television series Moonlighting.

The character of James Cole is a far cry from Willis' action heroes. Cole is both completely internalized and totally exposed. He knows something that no one else does, and when he confides it in someone, he is diagnosed as insane. He arrives in the film's present day naked and drooling, muttering to himself, devoid of bravado. He is bald, cut and bruised, and hardly heroic.

"It was his idea to shave his head, and it changed him a lot," Gilliam said. "It makes him much stronger, much more dangerous. He looks like a prisoner from a Soviet gulag ... Bruce has got one of the great architectural craniums in the world! It's just a great, beautiful thing to photograph." In Bruce Willis, Terry Gilliam got a creative partner as much as a cast member. But that doesn't mean it wasn't work: Gilliam started off filming by presenting Willis with a list that detailed the actor's performance cliches, with the instruction to avoid all of them.

Brad Pitt breaks out

Previous to 12 Monkeys, Brad Pitt had begun to make a name for himself as a strong actor and a sex symbol. His breakout role in Ridley Scott's Thelma and Louise began his ascent in earnest, and his parts in A River Runs Through It and Legends of the Fall cemented his status. Another movie arrived in 1995 that confirmed his acting chops: David Fincher's Se7en.

Yet it was 12 Monkeys that allowed Pitt to blow up. His unhinged performance as Jeffrey Goines was unlike anything audiences had seen from him up to that point. Goines is funny and terrifying at the same time, and a brutally effective red herring. Pitt's dedicated, maniacal performance is key to the audience's (and the film's protagonists') belief that he must be the guilty party. Part of this success comes from the fact that Pitt did his homework: He sought out Dr. Laszlo Gyulai of the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine for help shaping Goines' mannerisms.

Optometrist Mitchell Cassel also played a role in the film by making the contact lenses that gave Goines his misdirected iris. Very often, such costume lenses are like any other type, and vision is not impaired. In this case, however, Cassel noted that Pitt "could not see out of that lens at all ... he played that role with one eye."

What does "insurance" mean?

12 Monkeys ends on a mystery the individual viewer must approach according to their own philosophy. Dr. Peters, now known to the audience as the true eco-terrorist, boards his plane with the virus in hand. He sits next to a woman the audience knows as the astrophysicist from Cole's future. After brief small talk, Peters asks the woman what her line of work is. She replies she's in "insurance."

This scene can be interpreted positively: Since Cole didn't kill Peters, the astrophysicist is here to enact Plan B and ensure the virus doesn't kill most of humankind. But in order for the future scientists to know that Dr. Peters is the terrorist, James Cole has to make his journey. In order for future James Cole to be haunted by visions of a man being shot in an airport, he has to witness the event as a child, which we see happen. The young Cole seeing the older Cole shot dead suggests that the loop of circumstances has not been broken.

Is the astrophysicist ensuring that the virus is never released, or is she ensuring her own future by making sure it is? Can the scientists learn how to deliver Cole to the past without errors? Is time stuck in a loop? 12 Monkeys doesn't hand you a concrete answer. Instead, it makes the daring move of leaving it in your hands.