The Worst Movies By The Best Directors

Country singer Johnny Cash once said "You build on failure. You use it as a stepping stone." It's a truism that applies to all walks of life...even the careers of great filmmakers. The likes of Steven Spielberg, Spike Lee and The Wachowski Sisters are beloved around the world for their cinematic triumphs and understandably so. But their films that missed the mark can be just as important to examine and not just for the sake of contrarianism. Looking over the less-acclaimed efforts of great artists can provide valuable insight into their artistic process. Did these weaker movies come about because the filmmakers were just starting out and were honing their craft? Were they later efforts that come up short because they were too busy imitating the past?

These less-beloved titles are not the defining works for people like Francis Ford Coppola. They are, as Johnny Cash put it, "stepping stones," smaller pieces in a larger career. There's still value in these projects, just as there is value in examining what went wrong in the worst-reviewed movies from some of the best directors of all time.

Spike Lee and Miracle at St. Anna

With 2008's Miracle at St. Anna, director Spike Lee aimed to make a war movie like no other. Based on a book of the same name by James McBride (who also wrote the screenplay), it told the tale of four Buffalo Soldiers becoming detached from their unit and finding shelter in a Tuscany village. It was an ambitious project, much like all movies from Spike Lee. However, whereas other ambitious projects from Lee have yielded acclaim, the critical reception for Miracle at St. Anna was far more negative and widely directed at Lee's expansive canvas.

To be fair, reviews for Miracle at St. Anna were at least more mixed than outright toxic, with many observing that the feature did have its share of successful moments. However, glimpses of potential were largely overlooked in favor of Miracle at St. Anna's most widely noticed flaw: excess. Whether it was in regards to its runtime or the presence of a widely-disparaged framing device, critics found Miracle at St. Anna to be too much movie for too little of a rewarding experience. "There's a perfectly fine, Sam Fuller-ish, 90-minute war movie on a worthy subject trapped somewhere in the self-indulgences of Miracle at St. Anna," opined Lou Lumenick. Clearly, the kind of rave reviews that have greeted Spike Lee movies both old (Do the Right Thing) and new (Da 5 Bloods) were in short supply for Miracle at St. Anna.

The Coen Brothers and The Ladykillers

Through their respective careers, Joel & Ethan Coen and Tom Hanks have both been widely praised for their creative efforts. While they may follow different creative visions individually, putting them together for a dark comedy would still seem to be a recipe for a guaranteed critical smash. Such a conceptually foolproof collaboration emerged with the 2004 film The Ladykillers. A remake of the 1955 British dark comedy of the same name, the pairing of the Coens with Hanks did not yield the critically acclaimed results one would expect.

To be certain, The Ladykillers did not receive universally negative marks. David Edelstein of Slate, for instance, called it "a very pleasant cartoon for grown-ups" while reserving special praise for the casting and the use of music. However, the majority of reviews for the movie were mixed and echoed the sentiments of Nev Daniels of BBC, who remarked that "you'll have a hard time caring about any of the stereotypes strolling through this exaggerated, insincere world." While in many instances the stylized humor of the Coen Brothers has elicited as much praise as it has laughs, their approach in the case of The Ladykillers just didn't slay critics. With these sort of complaints, The Ladykillers earned a reputation as a movie that was less than the sum of its iconic parts.

Stanley Kubrick with Fear and Desire

Fear and Desire is the ultra-low-budget directorial debut of Stanley Kubrick and much of its reputation has been built around how the film was hard to get hold of for decades before being rediscovered in the 1990s. The fact that Kubrick himself wasn't a fan of Fear and Desire, to the point that he labeled it "a bumbling amateur film exercise", hasn't helped its reputation either. However, that shouldn't overshadow the film entirely. Though Fear and Desire's critical reception is handily the weakest of any of Kubrick's movies, it has generated some positive remarks in the years since its rediscovery.

Nick Schager of Slant complimented Fear and Desire's evocative atmosphere, even while noting that "the constraints of Kubrick's $50,000 micro budget and sparse, skeleton crew are all too apparent as the film begins to wander, adrift like its own marooned GIs." Janet Maslin of The New York Times expressed similarly mixed but admiring emotions in her assessment that Fear and Desire was "uneven and sometimes reveals an experimental rather than a polished exterior [but] its overall effect is entirely worthy of the sincere effort put into it." While it's apparent that Kubrick's later directorial efforts would be much more consistent in quality, these reviews also highlight the moments in Fear and Desire that show glimmers of the qualities that would make Kubrick a cinematic titan.

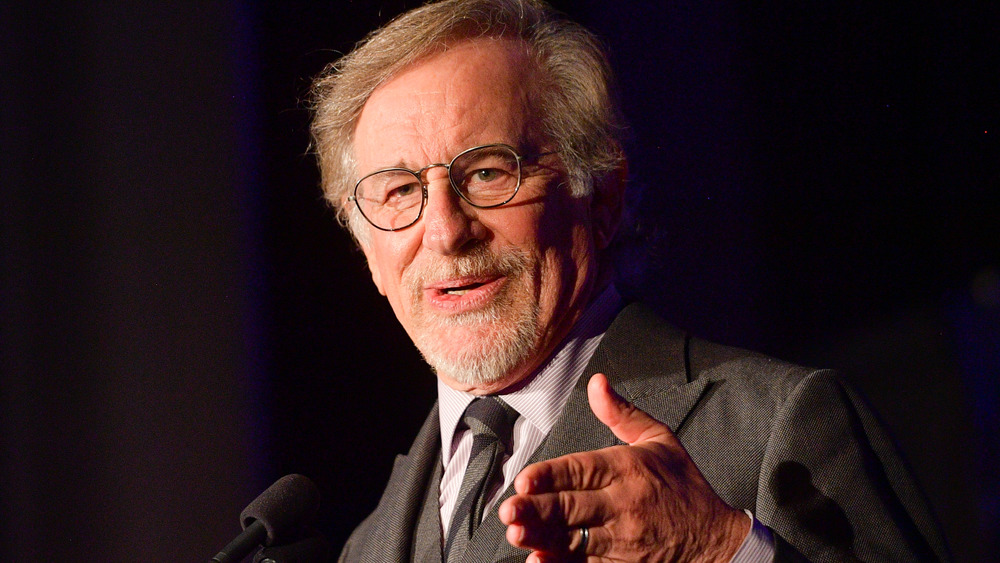

Steven Spielberg and 1941

Having just come off Jaws and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Steven Spielberg was riding high. Spielberg decided to use his clout to get a comedy about World War II entitled 1941 off the ground. Armed with an all-star cast that included John Belushi and Toshiro Mifune, not to mention a $35 million budget, Spielberg set out to prove he could execute comedy as well as a visual effects-driven spectacle. The results were a movie that remains Spielberg's worst-reviewed project to this day.

Across the board, 1941 was widely criticized for simply not being funny. "Billed as a comedy spectacle, Steven Spielberg's 1941 is long on spectacle, but short on comedy," declared Variety. Vincent Canby of The New York Times, meanwhile, observed that all the visual effects ended up working against the comedy. "The huge, profligate scale on which Mr. Spielberg has constructed 1941 works against the intended hilarity," said Canby. Such sentiments helped to give 1941 a reputation for being a critical dud.

In the years since, 1941, per The Los Angeles Times, has "gained a cult following" while the initial critical drubbing didn't slow down its director. Having directed Jurassic Park, Schindler's List and Lincoln (just to name a few) since 1941, it's fair to say Spielberg rebounded just fine from 1941's mixed reception.

Martin Scorsese and Boxcar Bertha

Today, Martin Scorsese is known for making some of the most thoughtfully crafted and sophisticated adult dramas of all time. The Irishman. Taxi Driver. Goodfellas. The list goes on and on. However, these aren't the only films to bear Scorsese's name as a director. In fact, in the earliest part of his career, Scorsese, like many noteworthy filmmakers of the '60s and '70s, was making features for B-movie maestro Roger Corman. The biggest collaboration between Corman and Scorsese was the 1972 crime drama Boxcar Bertha, which was headlined by Barbara Hershey and David Carradine.

Whereas modern Scorsese movies reliably get some of the best reviews of the year, Boxcar Bertha received mixed marks, though they were better than average by the critical standards of typical Corman-produced fare. The Chicago Reader dismissed the whole production as "Scorsese obliquely sketching out a few of his basic themes in a Bonnie and Clyde knock-off" while Consequence of Sound's rundown of Scorsese's filmography labeled Boxcar Bertha as "a little dated, cheap and sleazy." To the movie's credit, other critics like Roger Ebert and Keith Phipps praised Boxcar Bertha, with Phipps noting that the film provided a fascinating glimpse into Scorsese honing the themes and filmmaking traits that would come to define his career. Such an observation demonstrates that, even in the confines of a low-budget B-movie, Scorsese couldn't help but be the artist we all know and love today.

Francis Ford Coppola and Jack

The Godfather. Apocalypse Now. The Conversation. Throw a stone and you're bound to hit an all-time classic movie helmed by Francis Ford Coppola. But the iconic director's career was in a troubled place at the start of the 1990s. By 1992, Coppola had filed for bankruptcy three times, while his own The Godfather: Part III had become a go-to reference for underwhelming sequels. Worse yet, his directorial career would hit its critical nadir with the 1996 family drama Jack, the story of a child (played by Robin Williams) who physically ages at an accelerated rate while maintaining the intellect of a child.

The premise was meant to tug at the heartstrings, but critics were not moved. "Williams works hard at seeming to be a kid inside an adult body," wrote Roger Ebert. "But he has been ill-served by a screenplay that isn't curious about what his life would really be like." Nathan Rabin of The Dissolve, meanwhile, declared that with Jack, Coppola "didn't make a family film so much as a film destined to insult the intelligence of anyone old enough to read." On and on the criticisms went, with much of the vitriol directed at the film's cloying sentimentality and its inability to tackle its central story with any depth. Despite the viciously negative reviews, Coppola has stood by Jack and expressed befuddlement over the extreme hate it received.

James Cameron and Piranha II: The Spawning

James Cameron is a filmmaker known today for many things, including expansive spectacle, a fixation on digital 3D, and a love for deep-sea voyages. But there was a time when Cameron was a new filmmaker making his directorial debut with Piranha II: The Spawning. An infamously troubled production on which Cameron had no control over the final cut resulted in a fragmented and messy movie. Unsurprisingly, critics tore it to pieces like they were the film's flying piranhas attacking an unsuspecting beachgoer.

A frequent criticism in many of the reviews was that the story was poorly conceived even by the standards of B-movie trash. Meanwhile, in contrast to the groundbreaking visual effects deployed in future Cameron movies, the techniques used to render flying piranhas were widely disparaged. "If not for the brief involvement of mega-director James Cameron, Piranha II: The Spawning would be little more than a footnote in the annals of infamous Italian horror sequels," Dread Central succinctly noted. Such negative responses were a far cry from the mostly positive marks that would greet subsequent Cameron features. For his part, Cameron has taken a light-hearted attitude toward the film, including a declaration during a 60 Minutes interview that Piranha II was "the best flying piranha movie ever made." Now there's a quote you can put on a DVD cover!

Jonathan Demme and Last Embrace

Upon his passing in early 2017, The Guardian observed that director Jonathan Demme "was an artist as well as a craftsman, with a flair for grabbing the audience and not letting go." It was one of many distinct elements of Demme's highly acclaimed body of work, which included directing the Best Picture-winning feature The Silence of the Lambs. However, one of the more forgotten entries in Demme's filmography was his 1979 thriller Last Embrace, which starred Roy Scheider and Janet Margolin. Whereas many of his best movies blazed new trails and delivered unique imagery, Demme's Last Embrace was widely critiqued for being formulaic rather than suspenseful.

"Mr. Demme's handling of [the story] is more conventional than need be," lamented The New York Times. "The material is the sort that might be liberated by the imagination of Alfred Hitchcock." A similar sentiment was expressed by Slant Magazine, which observed how Last Embrace "contains only sporadic moments of the filmmaker's eccentric personality." More positive assessments of Last Embrace have emerged through outlets like Time Out, but by and large, Last Embrace has taken on a reputation of being one of Demme's most disposable works, an outlier among the movies that earned Demme a reputation for being "an artist as well as a craftsman."

The Wachowski Sisters and Jupiter Ascending

The Wachowski Sisters have always shown such bold imagination in their assorted directorial efforts, with sci-fi movies like The Matrix, Cloud Atlas and Speed Racer pushing the envelope rather than adhering to the norm. Their 2015 film Jupiter Ascending was certainly not short on ambition, given that it was a completely original work that combined critiques of capitalism with winged dogmen aliens. Jupiter had the creative audacity of earlier Wachowski movies but generated far less praise than their prior directorial efforts. Whereas 1999's The Matrix was widely hailed as a breakthrough for American sci-fi cinema, Jupiter Ascending was largely treated as a big-budget misfire.

Most reviews touched on the movie's jam-packed, impenetrable script and the puzzling lack of agency for protagonist Jupiter Jones (Mila Kunis). Joe McGovern of Entertainment Weekly described the blockbuster as "just another incoherent sci-fi spectacle" while Monica Castillo noted that Jupiter Ascending suffered because "too many characters clutter the narrative, while the central figure lacks a compelling arc." While Jupiter Ascending was initially scorned, Eddie Redmayne's campy performance as the film's villain has found devotees, like Vanity Fair writer Laura Bradley. Meanwhile, the film as a whole has managed to find a cult following in the years since its release. "This movie may be garbage," wrote Donna Dickens of Uproxx. "But it's our garbage!"

Alfred Hitchcock with Juno and the Paycock

Over the 51 years that Alfred Hitchcock helmed feature-length movies, he delivered some of the most revered films ever to grace the silver screen. However, a much less positive reception greeted his second-ever film with sound, Juno and the Paycock. An adaptation of the Sean O'Casey play of the same name, the film explored what happens when sudden wealth (via an inheritance) falls upon the arrogant Captain Boyle (Edward Chapman).

Rather than being the kind of terse thrillers Hitchcock would become widely associated with, Juno and the Paycock was a comedy, albeit one with a dark streak (including a bleak ending). Perhaps there's a reason Hitchcock didn't regularly return to this genre, considering the dismal critical reception that greeted Juno and the Paycock. A recurring critique of the production was how it failed to properly adapt its source material into a viable film. TV Guide observed that Hitchcock did "little with it other than film the stage play" while Emanuel Levy despaired how Juno and the Paycock "has more pathos than humor or wit, two attributes of the director's later and better work." Hitchcock helmed a wide variety of movies during his career as a filmmaker but few them generated as much near-unanimous disdain as Juno and the Paycock.

Quentin Tarantino and Four Rooms

Quentin Tarantino has long said he'll only direct 10 feature-length movies before going into a self-imposed retirement. If one wants to get technical about it, however, Tarantino has already directed 10 movies if one wants to count his segment in the film Four Rooms. This production was a 1995 anthology feature comprised of a quartet of segments directed by Tarantino, Robert Rodriguez, Alexandre Rockwell and Allison Anders. Despite so much high-profile talent behind and in front of the camera (Tim Roth and Madonna were among the big-name actors in the cast), Four Rooms scored a poor response in its initial theatrical release.

Desson Howe of The Washington Post lamented that the film as a "whole ends up as strong as its weakest link," though he did reserve praise for how Tarantino's segment maintained the director's signature style of humor. James Berardinelli of Reelz View, meanwhile, put the blame for the underwhelming nature of Four Rooms on the running time of the individual segments. "Twenty minutes isn't enough time to develop much in the way of characters or story," observed Berardinelli. Tarantino has experienced constant praise for his directorial efforts over the last three decades but a glaring exception is his work behind the camera on Four Rooms.