Why The Title Of Breaking Bad's 'Ozymandias' Episode Is So Important

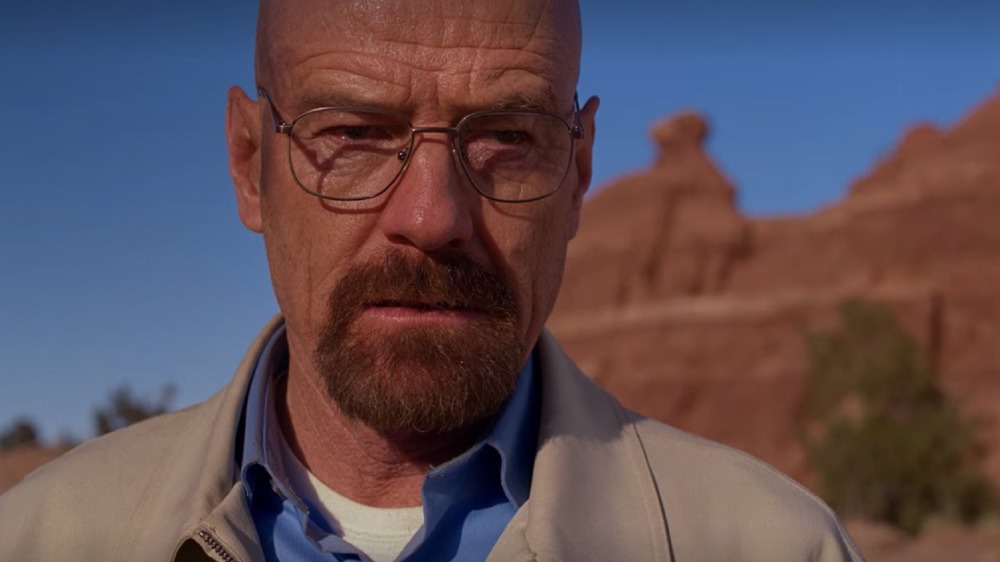

Indisputably one the best episodes — if not the best episode — of Breaking Bad is the series' third-to-last, "Ozymandias." In the course of its 47-minute runtime, we watch as nearly everything and everyone that means something to Walter White (Bryan Cranston) is either taken from him, destroyed by him, or abandons him in spectacular fashion.

The episode features a sequence of absolutely jaw-dropping moments, including: the merciless execution of Hank (Dean Norris) by Uncle Jack (Michael Bowen); Jack's crew stealing most of Walt's precious money; Walt's furious demand for Jesse's (Aaron Pinkman) demise; Marie (Betsy Brandt) and Skyler (Anna Gunn) finally revealing Walt's drug business to a gobsmacked Walt Jr./Flynn (RJ Mitte); Skyler pulling a knife on Walt and him kidnapping baby Holly as he flees; Walt calling to try and absolve Skyler of his crimes before turning the baby over to a firehouse; and, finally, Walt getting a ride from the Disappearer. By the end of the episode, it's clear that the only friend Walt has left in the world is one dust-covered barrel of cash and that he has failed at his prevailing mission to protect his family.

Like several other episodes of Breaking Bad, the title of "Ozymandias" has a deep metaphorical significance to the story of this installment, as it relates back to a very famous 19th Century poem of the same name and the much more ancient historical figure upon whom that piece of literature was based.

Look in a book

"Ozymandias" is a clear reference to the 1818 Percy Bysshe Shelley poem of the same name, which was also read in full by Walt in voiceover for a promo of Breaking Bad's final episodes. The brief poem centers on a traveler who comes across a fragment of a statue created to honor the great "king of kings," Egypt's Ramses II, but which is now just a lonely relic, broken and half hidden in an ocean of sand. The full text:

I met a traveller from an antique land

Who said: Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them and the heart that fed:

And on the pedestal these words appear:

'My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!'

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

Scholars have long interpreted that the poem speaks to the fragility of life and the inability for even the most accomplished and self-aggrandizing ruler to preserve himself from the inevitable erasure of time. Ramses II was known for engaging in several expansion and reclamation wars, launching a prolific building program for new temples and cities, and for putting his face on many, many statues, including one which was found toppled in ruins in 1817 and inspired Shelley's poem. And Shelley's version of "Ozymandias" isn't the only one that reflects upon the discovery of Ramses' broken legacy and thus bears some symbolism for the story in Breaking Bad.

There's more to the story

Shelley's friend Horace Smith also wrote a separate poem about the same topic as a bit of competition with Shelley. Both entries were published in The Examiner over a matter of weeks in early 1818 and each used anonymous bylines. Smith's version was also initially titled "Ozymandias" but was later renamed with the mouthful moniker, "On a Stupendous Leg of Granite, Discovered Standing by Itself in the Deserts of Egypt, with the Inscription Inserted Below." The full text:

IN Egypt's sandy silence, all alone,

Stands a gigantic Leg, which far off throws

The only shadow that the Desart knows:—

"I am great OZYMANDIAS," saith the stone,

"The King of Kings; this mighty City shows

"The wonders of my hand."— The City's gone,—

Nought but the Leg remaining to disclose

The site of this forgotten Babylon.

We wonder,—and some Hunter may express

Wonder like ours, when thro' the wilderness

Where London stood, holding the Wolf in chace,

He meets some fragment huge, and stops to guess

What powerful but unrecorded race

Once dwelt in that annihilated place.

Like Shelley's, Smith's poem also reflects on the finding of Ramses' ruins in the desert, with a boastful inscription that has outlasted the actual statue. However, Smith's second verse indicates universal deterioration, not just for the so-called king of kings, and thus drives home the poetic notion that Ramses' isn't the only kingdom that will fall and decay over time.

Look closely for clues

Breaking Bad's "Ozymandias" features several moments that appear to be visual homages to Ramses' story and the pair of poems that describe it. At the end of the flashback scene that begins the episode, Walt, Jesse, and the RV all slowly evaporate from the shot, leaving just the vast desert behind them. Their meth temple — the RV — has disappeared, and not even a boastful inscription remains to show for it.

Then, after Hank is shot by Jack, Walt falls to the ground in shock and lands head down in the sand. The sight of him lying there greatly resembles the posture of the fallen statue of Ramses, down to the color of Walt's jacket matching the shade of sand and the positioning of his hands behind his back, bound with cuffs, resembling the shape of the broken statue. At the risk of pointing out the obvious, they are also each surrounded by the jagged rocks, trees, and sand of the desert landscape. This visual parallel indicates that with the death of Hank, Walt's carefully crafted empire has finally begun to crumble.

Later, when Jack unearths and steals all but one of Walt's barrels of money and allows him to drive away, Walt looks back upon two pieces of disturbed sand in the rearview mirror. They are shaped somewhat like footprints as a potential nod to a separate finding of Ramses' feet, but more importantly, those spots contain the bodies of Hank and Gomez and thus a piece of Walt's kingdom that has been lost to the sand.

A new endgame

"Ozymandias" also echoes the theme of impermanence found in both poems. Like Ramses, Walter White has prided himself on being in the "empire business," and he has continued to boldly expand and build his wealth and dominance at all costs, including war. However, also like Ramses, neither Walt nor his kingdom are eternal. Following the death of Hank and the heist of most of his money, the rest of Walt's life begins to crumble very quickly. Skyler refuses to let herself or Walt Jr. join in on Walt's escape mission, the police are absolutely on his tail, and even after Walt tries to take Holly with him, the baby makes it very clear that she wants her "Mama." By the time the Disappearer's car arrives, Walt's throne has been thoroughly broken.

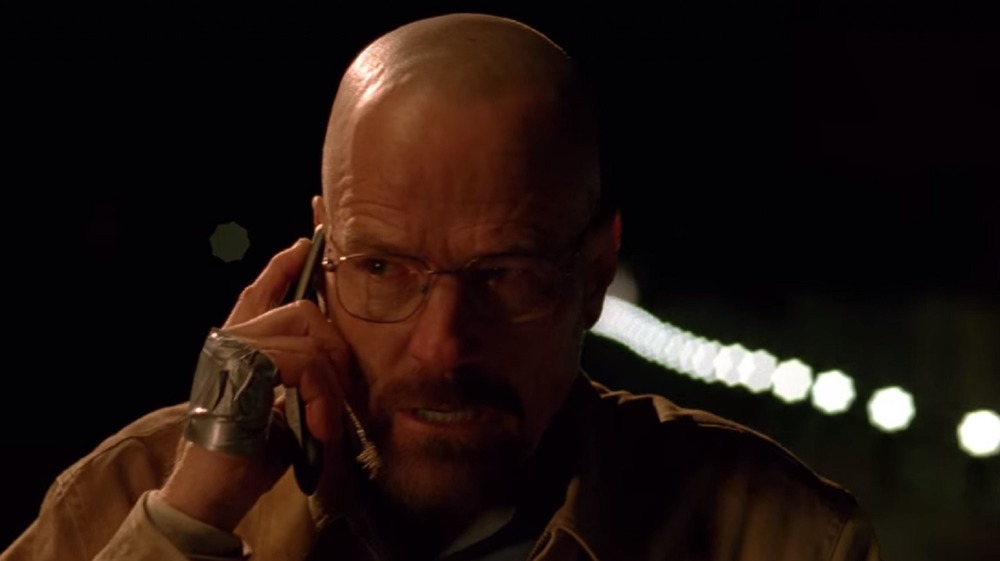

In the end, there is only one thing Walt can do for his family, and it is to become more Ramses-like than he has ever been before in a very specific way. In their poems, both Shelley and Smith incorporate parts of Ramses' statue's inscription as memorialized by Diodorus Siculus in his Bibliotheca historica, but the full quote is helpful here: "King of Kings Ozymandias am I. If any want to know how great I am and where I lie, let him outdo me in my work." This mirrors the moment when Walt makes a call to talk to Skyler at home, knowing the police are listening in, and he insists, "You have no right to discuss anything about what I do. Oh, what the hell do you know about it anyway? Nothing. I built this. Me. Me alone. Nobody else!" Not only does he sound like the fabled pharaoh bragging of his accomplishments, but this is also Walt's last-ditch effort to save his kingdom from the complete ruin of Skyler being taken down with him.