The Untold Truth Of Gene Hackman

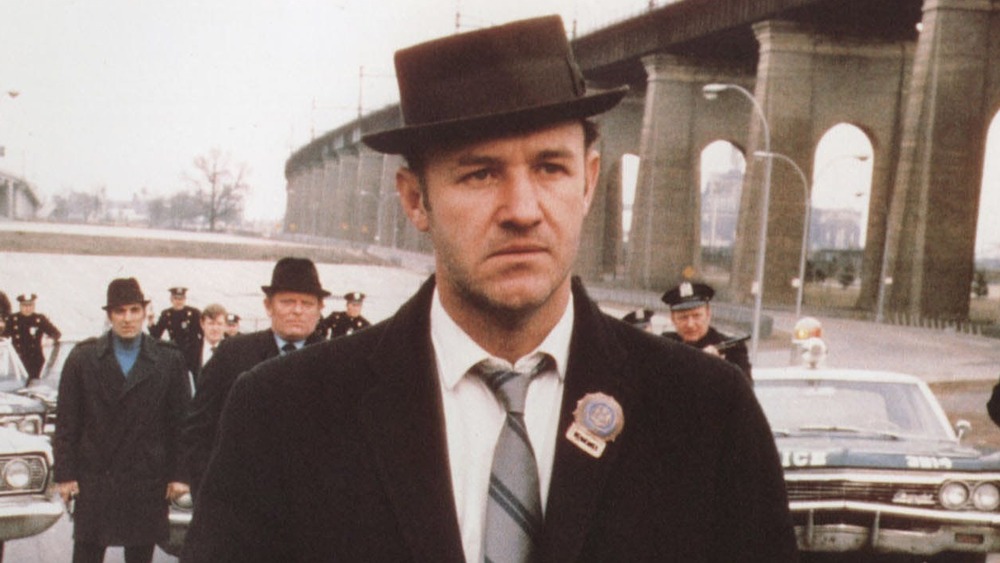

Gene Hackman's last feature film was 2004's Welcome to Mooseport, but all these years of retirement haven't dimmed his cultural presence. He's as iconic as ever. Whether he's playing a gleefully villainous Lex Luthor, an introverted and buttoned-up surveillance expert, or a driven and vicious cop, he's always been convincing. When he's on the screen, it's hard to look away.

He's collected multiple Oscar nominations and two wins, and that's just the start of an impressive list of award recognition and critical acclaim. Alan Parker, the director of Mississippi Burning, summed up Hackman's appeal perfectly in a discussion with Film Comment: "He is incapable of bad work. Every director has a short list of actors he'd die to work with, and I'll bet Gene's on every one."

Hackman has often been reluctant to give interviews, however. While his screen presence is magnetic, the man behind it can be harder to spot. Here, we pull him a little further into the spotlight. This is the untold truth of Gene Hackman.

Hackman's love of acting started out as escapism

Gene Hackman grew up during the Great Depression, when movies were a cheap and easy escape from a gray day-to-day life. They distracted him from a sometimes tumultuous childhood. His father left his family behind without even a real goodbye. All Hackman got, he said in an interview with Vanity Fair, was a wave. It instilled in him a real understanding of "what one small gesture can mean."

He and his mother soon moved in with his grandmother, who didn't have a high opinion of him. There was never a lot of money — he once spent a night in jail for shoplifting candy and soda.

But when he went to places like the historic Fischer Theatre, he could step into another world. The movies gave him screen heroes like his favorite stars Jimmy Cagney and Edward G. Robinson — and sometimes knocked him back to reality with more dashing favorites like Errol Flynn. "I would come out of the theater and see myself in the mirror of the lobby," Hackman said, "and be stunned that I didn't look like him." But in his daydreams, he could have just as many swashbuckling adventures.

Seeing his first movie convinced him he wanted to be an actor, one who would maybe be more Cagney than Flynn. And his mother believed in him. As Hackman confirmed in an interview with GQ, she told him that someday she hoped to see him up on the big screen.

He enlisted in the Marines when he was only 16

He had to lie about his age, but Gene Hackman managed to enlist in the Marines in 1947, when he was still 16. He wanted to change his life.

Being young didn't make him more obedient: leaving his post without permission got him demoted three times. "I have trouble with authority," Hackman said in an interview with Larry King. "I was not a good Marine."

It took a convincing performance to get him into the Marines. In a way, it was one of his first acting jobs. The service went on to give him experience as a volunteer disc jockey and radio reporter, and most of his military service was spent working as a field radio operator. It all added up to a kind of training in communications, so when Hackman left the Marines, he used the GI Bill to continue his studies. He enrolled at the University of Illinois, where he studied TV production and journalism, leaning into his military experience, and then went to the School of Radio Technique in New York.

Hackman's USMC service has stayed with him, and he even narrated a 2017 documentary — We, the Marines — about the Corps.

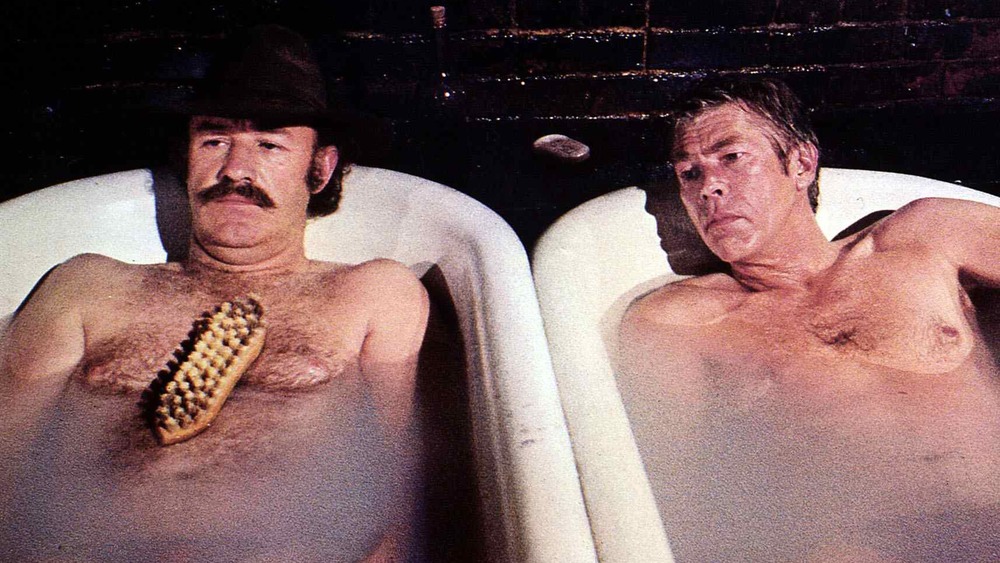

Along with Dustin Hoffman, he was voted 'Least Likely to Succeed' by his acting classmates

Gene Hackman and Dustin Hoffman both studied at the Pasadena Playhouse in 1952. In many ways, Hackman told Film Comment, they were the two odd men out. Hackman's Marine Corps years made him an unconventional acting student, and he had a life milestone most of his classmates didn't: He was already married. Meanwhile, Hoffman's unconventional fashion sense got him dubbed a beatnik, and his shortness seemed to put him out of the running for traditional stardom.

Hackman was taller, but he still faced many of the same criticisms his friend did. He simply didn't look like a movie star was supposed to, and everyone in the business, from casting directors to his acting teachers, defined him as a character actor. "I accepted the limitation," Hackman said, "of always being the third or fourth guy down, and my goals were tiny. But I still wanted to be an actor."

But his classmates didn't see that in his future, and they voted Hackman and Hoffman as that year's "least likely to succeed." Unsurprisingly, Hackman didn't stick around the Playhouse very long after that. He and Hoffman, of course, have both had storied careers that have since proven their detractors wrong. It's harder to say what happened to the rest of the class.

A late starter, he didn't have his first film role until his thirties

At first, Gene Hackman thought of himself as being destined for a theater career. His lack of traditional leading man looks might be a disadvantage in the movies, but it was different on stage. "In the theater you can play characters totally different from your persona with the aid of make-up, costumes, and so on," Hackman explained. He worked steadily in theater and live television, and he could have made a career there. Eventually, he even won the Clarence Derwent Award ("Most Promising Male") and got a Broadway break.

His movie work, on the other hand, had been limited to an unnamed and uncredited part in 1961's Mad Dog Coll. But things were changing in the movies. A door was opened by Marlon Brando, whom Hackman credits with causing "something of a groundswell about men who didn't have conventionally handsome faces." More roles for guys like him were starting to appear.

In 1964, he had his first named movie part in the neo-noir Lilith, and then he was on a roll. Warren Beatty, the star of Lilith, pressed for Hackman to be cast in Bonnie and Clyde, where he was a hit. His performance as Buck Barrow netted him an Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actor — just three years after he played his first named character in the movies.

Gene Hackman almost starred in The Brady Bunch

It's an especially surreal casting might-have-been, but Gene Hackman was one of the top contenders for the role of amiable sitcom dad Mike Brady. Instead, he went on to become a major Hollywood career, often playing violent, hard-bitten men, like The French Connection's Popeye Doyle or Unforgiven's Little Bill, who would never have fit into a family sitcom. But if Brady Bunch creator Sherwood Schwartz had gotten his wish, Hackman could have been a familiar face in the grid of The Brady Bunch's opening credits.

Instead, the role went to Robert Reed. Network executives saw Gene Hackman as a nobody, even after the success of Bonnie and Clyde and his Oscar nomination. While it's common now for actors to move seamlessly between film and television roles, the line between the two industries used to be much thicker. Usually, though, you heard about TV actors trying — and often failing — to translate their success to the movies.

That wasn't the case here. Hackman now had the beginnings of movie success, but the network didn't think he had enough recognition with viewers. Robert Reed, on the other hand, had already co-starred in the popular legal drama series The Defenders. For this brief window of time, he was the more popular actor, and this gave both of their careers a major turning point.

Honesty is at the core of Gene Hackman's performances

In acting, Gene Hackman values honesty above all else. He has to find and convey the essential truth of his character's nature, without regard for how it makes him look or feel. He tries not to worry about how the audience will feel about him. It's one of the approaches he picked up from George Morrison, his most useful and most beloved acting teacher, who also taught him the relaxation exercises he made a habit of doing before every scene.

"I say to portray what is on the page, instead of what maybe people might think of me or what I would like them to think of me in terms of personality or charisma," Hackman said in an interview with GQ. It doesn't matter if he thinks the script is good or bad — he wants to work with what it gives him and find the truth in it.

And this isn't just Hackman's own self-assessment. His directors have seen this in him too. Arthur Penn, who worked with Hackman on several films, including Bonnie and Clyde and Night Moves, told Film Comment, "He is an extraordinarily truthful actor, and he has the skill to tap into hidden emotions that many of us cover over or hide — and it's not just skill but courage."

Hackman summed it up simply: "You cannot play a lie."

Looking back, he wishes could have done more comedic and romantic roles

The French Connection helped make Gene Hackman a star. But the kind of intensity behind that violent, aggressive performance was hard to summon time and time again. For a while, though, he didn't have much of a choice. "Unfortunately," Hackman explained to Film Comment, "in film one is cast so close to type, and I keep getting offered similar roles."

"I have regretted not letting more of my career go toward comedy, or toward romantic portrayals," Hackman told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. "I loved the Superman assignments, on account of the comic villainy I was allowed to do there, and the spoofing good humor in Young Frankenstein, and the idea of myself as a romantic leading man — well, let's just say Twice in a Lifetime was a very real pleasure." Luckily, some of Hackman's later films offered him more of those opportunities. This can make us all feel just a little better about Hackman's final performance being stuck in 2004's lackluster Welcome to Mooseport. Maybe it was a strange note to go out on, but it gave us an intriguing look at the comedy career Hackman never fully had.

Gene Hackman has always struggled with being 'an angry young man'

Gene Hackman believed trouble usually found him, not the other way around. Regardless, his struggles with his temper are well-documented. Even in his eighties, he admitted to GQ, he still saw himself as an "angry young man." It depressed him a little: "I hate that idea," Hackman said, "because it's the antithesis of the creative spirit and what it takes to be a creative person. But you do, sometimes, what happens in the spur of the moment. I, unfortunately, kind of react."

Sometimes that reaction was physical. When he was 71, Hackman's heated argument over a fender-bender took a dramatic turn, and he punched the other driver several times. It also sometimes came out on set, even when he wasn't in character. At the New York Film Festival, his castmates on The Royal Tenenbaums remembered Hackman insulting director Wes Anderson and being generally intimidating, so much so that Bill Murray came in on his days off to act as a buffer between Anderson and the more volatile Hackman.

But there was always a pathos to Hackman's anger, maybe because he knew how destructive it was and wished he could get rid of it. Even if the Tenenbaums shooting was stormy, Gwyneth Paltrow still had fond memories of him: "He was a bear of a guy but I also found something very sweet and sad in there and I liked him a lot."

Gene Hackman almost turned down his role in Unforgiven because of the movie's violence

Clint Eastwood's gritty Western Unforgiven features one of Gene Hackman's most iconic roles. But it came at a time in his career where he wasn't sure he wanted it.

For one thing, he had his family to think of. His daughters didn't like how many of his movies had him playing violent men. (It's part of why he's not in The Silence of the Lambs.) And Hackman himself had some reservations: A medical scare in the '80s had changed his perspective, and by the time Unforgiven rolled around, Hackman had been turning down more violent scripts for years. It was well-trodden ground for him, and he just wasn't sure he wanted to do it anymore.

It took Eastwood himself to convince Hackman to give the movie a chance. He advocated for the script: While Unforgiven would have violence, it wasn't going to be mindless. The film would show the true weight of violent actions.

Little Bill wound up being one of Hackman's favorite parts. In a pre-release interview, he stated, "About every third or fourth movie I'll do is of really serious, personal interest to me ... [this] is one of those third or fourth pictures in the cycle. It has so much to say about the issue of violence, about the myth of heroism, that I found a lot of my own attitude toward violent entertainment articulated in the characters and their situations."

He's an amateur -- and award-winning -- race car driver

Gene Hackman has plenty of run-of-the-mill interests. He likes art — he even does some painting himself — and football (he roots for the Jacksonville Jaguars). But there was always an impressively physical, dangerous streak to how he spent his leisure time, too.

Most notably, in the 1970s and 1980s, he got behind the wheel of a race car. And when he was there, he was remarkably good: He won several races, often raced modified sports cars, and even briefly considered taking the sport more seriously and doing it at a higher level. It ultimately would have interfered too much with his acting career to be a real possibility, however.

And while he had some of the skills he needed on the track, he wasn't sure he was the right mental fit for the job. "I think you need a tougher personality than I have," he reflected. "You have to be harder than I'm capable of ... You have to be very competitive. You need to have that edge about you. The good ones all have that." It's a good thing for cinema that Hackman ultimately thought himself a better fit for acting than racing. Besides, it wasn't all or nothing. The choice to continue his sterling movie career also left him with one of the world's coolest hobbies.

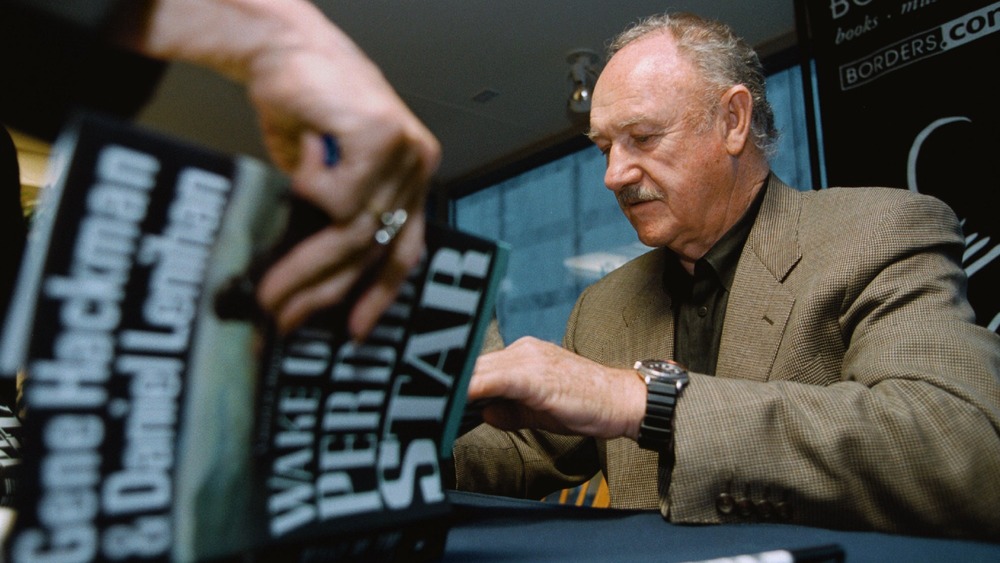

Gene Hackman's second career as a novelist

Gene Hackman retired from acting in 2004, when his doctor warned him that his heart wouldn't take too much more stress. But he hasn't completely stopped working. Instead, he's just changed his focus.

In 1999, he released first co-authored book — the historical Western The Wake of the Perdido Star, written with Daniel Lenihan. Retirement has let him concentrate on his writing. Hackman told Empire, "It's very relaxing for me. I don't picture myself as a great writer, but I really enjoy the process... it is stressful to some degree, but it's a different kind of stress. It's one you can manage, because you're sitting there by yourself, as opposed to having 90 people sitting around waiting for you to entertain them!" With writing, his first real audience is himself, and he has far more time to tweak his work to get it exactly where he wants it.

He co-wrote two more books with Lenihan and eventually branched out to writing on his own, publishing the thriller Pursuit and the Western Payback at Morning Peak.

Writing, Hackman said in an interview with Writer's Bone, helps keep him relevant: "My other job, that thing I did for 60 or so years, was getting tougher as the years slipped by. The characters bouncing around in my head had to play out."

Post-retirement, he'll still do the occasional documentary

Even though Gene Hackman has left most of his onscreen stardom behind him, there's one kind of film work he'll still do: documentaries.

He's provided narration for several, most notably ones that connect to his military service — The Unknown Flag Raiser of Iwo Jima in 2016 and the short film We, the Marines in 2017. His recent documentary work has often spotlighted someone else, which befits someone who's stepped away from the limelight. Hackman has made appearances in a documentary on Clint Eastwood, a short about the gone-too-soon actor John Cazale, who worked with him on The Conversation, and an American Film Institute tribute to Warren Beatty, who helped give him his first big break. Documentaries have also been a way to spend more time on his hobbies, and he narrated four episodes of America's Game: The Super Bowl Champions.

But his most surprising appearance was on Diners, Drive-ins, and Dives, where he was just enjoying his breakfast in a Santa Fe diner — Harry's Roadhouse — when Guy Fieri arrived.

Hackman did make one sly attempt at doing another kind of film work, he told The Independent, when he ran into a movie being shot near his home. "There was a young assistant director on a backstreet in Santa Fe, directing traffic," Hackman says. "I pulled up next to her and asked if they were hiring extras."

Her response? "No, I'm very sorry, sir." And Hackman drove on.