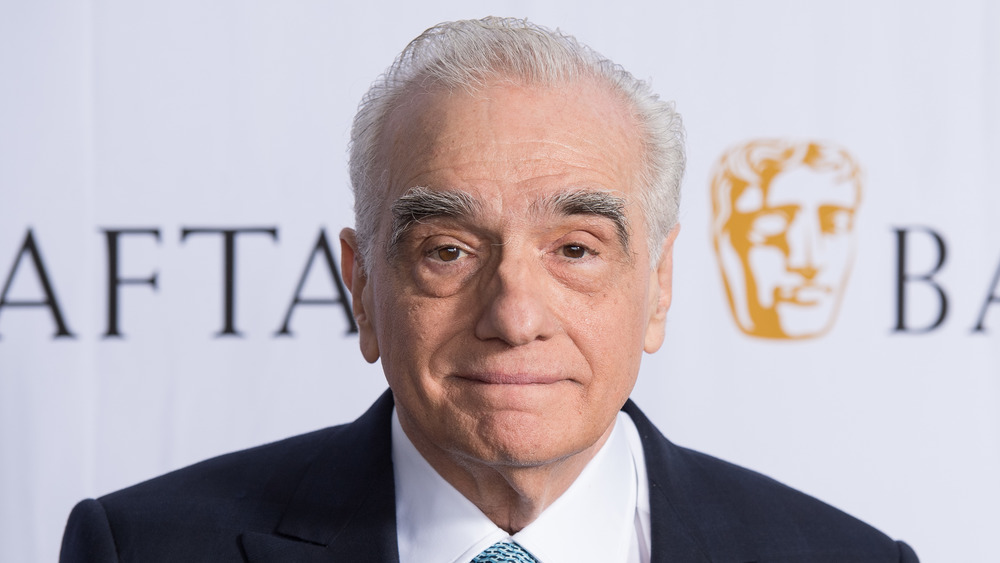

Rules Actors Have To Follow In Martin Scorsese Movies

How does Martin Scorsese manage to pull off such high-caliber films decade after decade, pumping out "instant classics" like The Irishman in 2019 even as he lives to see his earlier work age gracefully into the truly time-honored canon?

While there's reportedly a lot of room for improvisation on the sets of his films, this doesn't mean there are no rules (or that a reliance on improvisation isn't one of them!). In fact, it's precisely Scorsese's unique habitual directing style that allows him to accomplish feats of cinematic genius so regularly.

From cast to crew, there are certain particularities that everyone working on a Scorsese set learns to adapt to, but they differ greatly from the strictures of Alfred Hitchcock, for example, who maintained a far more rigorous and controlling regime in order to achieve his masterpieces. Scorsese believes that actors are a most prized resource, and the expectations he places on them help guarantee iconic performances, expertly crafted films, and even lasting personal and professional relationships. Scorsese stands alone in the way he brings his values to his sets, and he shares them not only through directing people but connecting with them.

Expect to get vulnerable in a Martin Scorsese movie

Scorsese has been described as more actor-focused than plot- or even character-focused, known for having heart-to-hearts with his actors and really getting at who they are and how he can help them bring their best to the piece. He looks for "the heart of the story through the actors that he works with," Leonardo DiCaprio told The New York Times, with plot as a secondary concern.

This is surprising to learn given the engaging and elaborate storylines that often decorate Scorsese films. By choosing to focus on the actor rather than the plot or even the characters, the director builds a foundation from which both plot and character can spring. But in order to build that foundation, you have to open yourself to the particular intimacy that can only be found, DiCaprio assures us, on a Scorsese set, as he structures the entire film around what his nurturing can bring out in his actors.

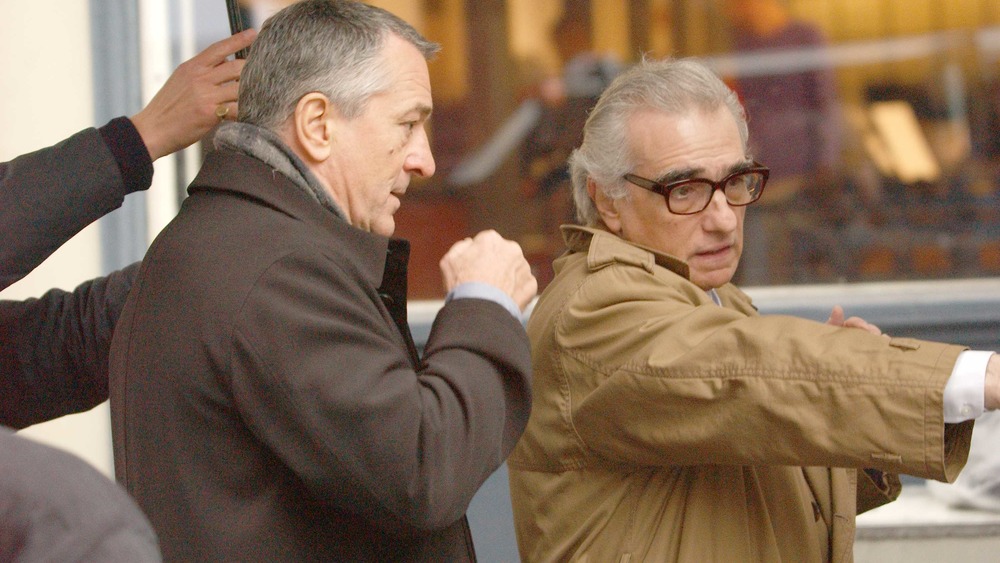

Perhaps Scorsese has developed this pattern because of how meaningful his own background is to his work and his collaborations. He feels a marked kinship with Robert De Niro that's unspoken, a relic of growing up around the same neighborhood in Manhattan that to this day informs his conceptions of everything from comedy to communication. If his film genius comes from inside him, that's where he's going to search for it in his actors, too.

You've got to adapt to his singular focus

Whether it's honing in on an actor relationship or on the emerging dynamics of a scene, when Martin Scorsese engages his focus, it's impossible to interrupt. When a take is rolling, you'll always find the director glued to his monitor at video village, singularly attentive to the performance going on in front of him. The monitor's "video assist" that allows directors to see what's in frame is one of Scorsese's favorite cinematic inventions.

This ties into the fact that he often shoots with a single camera, a tactic that's responsible for one of his most iconic scenes, shot not only with a single camera but in a single take — the Copacabana scene in Goodfellas. Here, Scorsese uses his camera to develop characters' idiosyncrasies and vulnerabilities, treating both his monitor and his actors with the obsessive quality that characterizes his films themselves.

Of course, his singular focus is in fact the "unifying vision of an individual artist" (via The New York Times) that he describes as integral to true film art. Scorsese himself touts the individual artist as a risky phenomenon, and in that role, he strikes an ineffable balance. It's one that emphasizes unity as much as vision and doesn't exclude anyone, but rather, it enhances what everyone brings to the table. Under his watchful eye and video feed, expect to leave no stone unturned.

What makes a Martin Scorsese movie marvelous

For all his collaborative energy, Scorsese has a specific idea of what qualifies as true cinema. Remember his infamous rebuke of Marvel films? While it drew the ire of both moviegoers and moviemakers, it makes sense that someone who's studied and practiced cinema as meticulously as Scorsese would have a very particular idea of what it is and isn't.

Like much of Scorsese's film philosophy, he credits his personal disinterest in Marvel films to the circumstances of his childhood. Growing up on the Lower East Side was where Scorsese says he learned about acting, storytelling, joke-telling, and timing. His great admiration for film was something he grew up with and grew into. And because he grew up when he did, as he writes in his opinion for The New York Times, he "developed a sense of movies — of what they were and what they could be — that was as far from the Marvel Universe as we on Earth are from Alpha Centauri."

Much of what makes movies what they are comes from the actors, and this is critical for Scorsese collaborators to understand. Revelation and risk come from the complexities of people, and these are lost when the modern entertainment machine insists on fitting them into the franchise package. Scorsese will never lift the weight off an actor's shoulders and place it on flashy costumes, firefights, or CGI. Carrying that weight is the only superhuman feat he's really interested in.

You've got to trust the process

Scorsese loves in-the-moment discovery and experimentation. More important than acting is the ability of actors to "live in" the process of existing. They can be comfortable doing what feels right. Even if it feels "out there," Robert De Niro recalled to The New York Times, Scorsese may just tell you to try it anyway — you can always cut it out!

This has worked both to the director's benefit and detriment over the course of his career. The former is usually the case, but occasionally, something happens like it did in 1977 with New York, New York, where Scorsese permitted much of the dialogue to be improvised, resulting in difficulty putting it all together. But a penchant for improvisation also gave us De Niro as Travis Bickle delivering his iconic "you talkin' to me?" line.

Whatever improvisation has done for Scorsese's individual films, it's definitely been pivotal to the development of his sacred yet familiar reputation among the actors that he works with. For example, Leonardo DiCaprio has expressed confidence that without an incredibly high level of understanding and trust between everyone involved in 2013's The Wolf of Wall Street, the film — with all its raunchy subject matter — would never have come to fruition.

The massive trust Scorsese's actors place in him, and the level of enjoyment they get out of working with him, is a result of the director offering them his own trust and creating an environment where they can trust themselves.

You might get cut out of a Martin Scorsese movie

One rule that actors must indirectly learn to live by if they want to be involved with Scorsese is that you can't get too attached to certain moments or scenes of your performance. The director, who's been making lengthy films since long before The Irishman, likes to get a lot of footage, at least by industry standards, which means that there's also a lot that will end up left on the cutting room floor.

Though you may not guess it from the final runtimes of many of his classics, Scorsese has often butted heads with studio executives who invariably want to keep the features shorter. The double-edged sword of offering freedom to actors is that it also necessarily offers more material for the chopping block, a constant frustration to the filmmaker already.

In the end, this don't-get-attached rule is the same for just about all movies, regardless of director. But on a Scorsese film, there's an important difference. Whether it makes it into the movie or not, you can be sure the director is rooting for you during every second the camera is rolling. In a weird way, if you end up with what seems like a mountain of unused footage, it's actually a monument to how strongly Scorsese believed in what you were doing in those moments.

Get ready to learn (or make up) a new language

Martin Scorsese uses a lot of nonverbal messages, a communication style that's a built-in benefit of the depth he aspires to in his actor relationships. It's also a side effect of his comings and goings on set, which Shutter Island crew member Michael Nie told StoryFirst were very cloistered, with Scorsese arriving for a take once everything else was in place, retiring to his trailer when he'd gotten the perfect shot, and beginning the process again.

This compartmentalization means he can devote his full attention to whoever he's communicating with at the time, and this seems to be how he likes it. And Scorsese's ability to communicate unspoken sentiments with both cast and crew is evident, particularly in his interactions with cinematographer Robert Richardson, a recurring collaborator on films like The Aviator and Casino. "Because Scorsese is glued to his monitor and Richardson is glued to his camera," Nie explained, "the assistant director is the go-between."

The development of a nonverbal "shorthand" isn't an experience restricted solely to Scorsese's seasoned collaborators. Al Pacino, a relative newcomer to Scorsese productions, was able to reach a high level of communication with the director based on honesty, mutual respect, and very few words. But being able to reliably send and receive messages with Scorsese made Pacino feel seen, as if he weren't alone. The notion of speaking the same language is a common refrain among the director and those who've had the pleasure of working, speaking, and not speaking with him.

Stop, collaborate, and listen!

Multiple actors and critics have described Scorsese's style as intensely collaborative, which ties back into his oft-displayed affinity for connecting with his performers. Roger Ebert even commented in Scorsese by Ebert that the director brings this energy to his relationships with the wider film culture, as well. As Ebert wrote, "What Scorsese's camera says to me is not, 'look how I see this,' but 'look with me at this.'"

Collaboration can take many forms, from spontaneous experimentation to trusting one's actors as confidantes in the execution of the film itself. For example, the lifelong friendship and mutual artistic relationship between Robert De Niro and Joe Pesci began when De Niro saw Pesci in a low-budget 1976 thriller called The Death Collector and convinced Scorsese to cast him in his 1980 breakout role in Raging Bull. Not only has Scorsese encouraged collaboration on the set of his films, but he's also responsible, almost in the sense of a matchmaker, for facilitating collaboration between actors.

Half a dozen collaborations later between the two stars, in what seemed like an echo of that inaugural moment decades earlier, De Niro literally summoned Pesci from retirement (after 40 attempts) to appear in yet another Scorsese film alongside him. Now, we couldn't imagine The Irishman any other way. Only in Scorsese films could the input and relationships of actors have such profound results on final products like Raging Bull and The Irishman.

You talkin' to me?

Martin Scorsese spends time with actors in extended, closed-door rehearsals so that when they come to shoot the scene, they're beyond prepared. As an actor, one no-brainer rule is to be ready for these sessions and to try to make as much as possible of what essentially amounts to a personal masterclass.

Being on the same page from the moment the camera starts rolling is one of the cornerstones of Scorsese's prowess as a director and popularity among those he works with. It facilitates his nonverbal conversations and fosters a sense of trust and appreciation. During actual takes, then, Scorsese will offer minor adjustments to his actors because most of the major directing from their perspective has already happened one-on-one.

So as an actor, in addition to being prepared for those personal sessions, it's also critical to do away with your expectations of shooting the scenes themselves and be adept enough to tie the small critiques Scorsese gives in front of everyone to the core understanding of the character that he took the time to build up just with you.

On a Martin Scorsese movie, you've got to have a strong stomach

If you ever wind up in a Scorsese film, you can't shy away from the criminal and macabre, which have seemed glamorous to Scorsese since his youth and which he enthusiastically depicts down to the smallest details. Introduced to the somber culture of death early in childhood as an altar boy, as well as through some tragic losses as a teen, it's been something of a fixation for his entire career, even more so as he gets older. The influence of mortality as a concept is evident in almost every one of his stories, especially his many mob dramas where it's almost seen as a given.

Death, however, is more than "painting houses." It's present in every moral dilemma and moment of self-reflection, and it also appears in more and more of the aging director's thoughts in recent interviews. At the core of his films, Scorsese addresses human questions that play out in every person's mind, questions of identity and morality. But he depicts these questions, and how their stories play out, in what he himself describes (via Esquire) as a more "brutal" way because it's more direct. It's just one more manifestation of the intense communication philosophy Scorsese employs with actors and viewers alike.

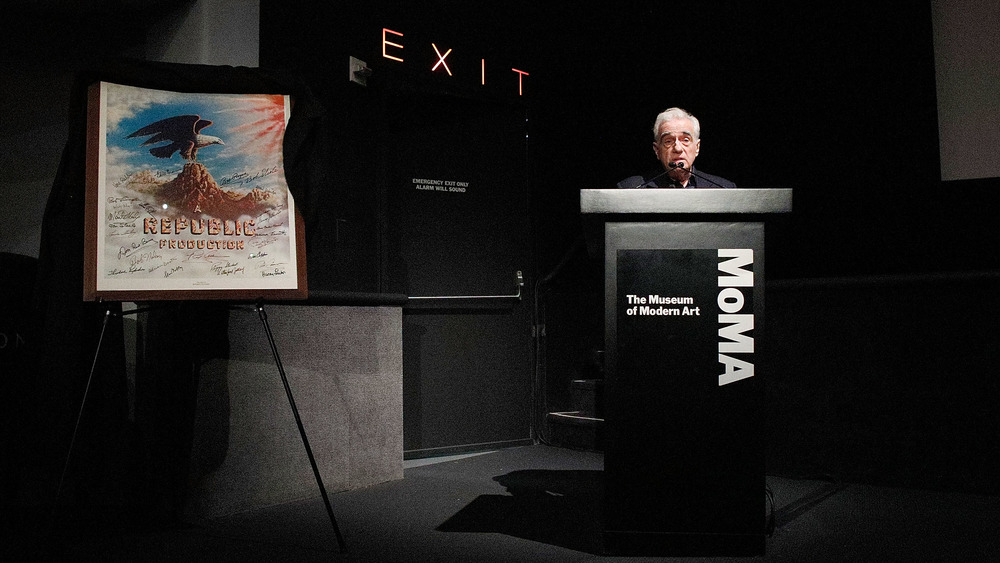

Be prepared to reminisce

Scorsese collaborators must remain conscious of the fact that they're actively contributing to a history their director has spent his life celebrating. Actors should be ready to get nostalgic and serious, not just about their own goals but the film industry as a whole. His collaborators should love the craft, as Scorsese has as a consumer and contributor, as well as an activist and pioneer in the film preservation sphere.

The way Scorsese relates so deeply to his actors and peers in the film industry is in fact directly related, DiCaprio told The New York Times, to his lifelong cinephilia. He has "learned as much as he can about the history of his art form" — arguably about as much as anyone can. And after everything he's learned, his focus is still the "one-on-one dynamic" between filmmaker and actor.

In addition to championing his actors, the acclaimed director also routinely supports other auteurs like Antoine Fuqua, Spike Lee, and many others by serving as an executive producer or promoter on their projects. He uses his platform to lift others up alongside him, remembering what it was like to learn cinema simply by loving it. This propensity for looking back with gratitude is a large part of what inspires him to pay it forward to countless members of his industry.

He wants to tell new stories

Despite his dogged loyalty to cinematic history, Scorsese wants each story to be a new one. After all, he's extremely cognizant of the limited time he has left to craft stories worth telling, as well as the fact that he has an incredibly recognizable style that he doesn't want to fall into the trap of constantly duplicating.

His legacy gives him and his collaborators the pressure and inspiration to innovate. How can you add meaningfully to a body of work and honor it without simply imitating it? A sense of sameness is a common ailment in today's entertainment industry, according to Scorsese, to the point that modern film franchises are lamentably "sequels in name but remakes in spirit."

Though we often find him working with the same actors, this conceivably means that he expects even more from those who are most familiar with his work. In The Irishman, for example, he sprung for expensive de-aging technology so that actors like De Niro, Pacino, and Pesci could play their characters over multiple decades.

Scorsese had initially thought that the only reason to do another mob drama like The Irishman was if it could confront new ideas. And his casting and de-aging decision truly captured the unique story of men whose lifespans force them to live with their decisions. Both exerting and exhilarating his distinguished cast with his approach, Scorsese invoked a fresh way to depict something new — watching the world change before the same set of eyes.

Don't expect a Hollywood set with a Martin Scorsese movie

Martin Scorsese has strong aversions to working with studios. At the end of post-production on The Aviator, the director was almost ready to quit the business of filmmaking due to the constant tension with the higher-ups in the studios involved. This kind of stress is especially frustrating for someone who recalls a healthier age of Hollywood in which the tension between the artistic and commercial sides of the industry was productive and forced innovation.

With that era of Hollywood ostensibly gone, Scorsese more and more prefers independent financiers, which in turn affects the type of experience that cast and crew have on set. Whereas many films today are, as Scorsese puts it, "perfect products manufactured for immediate consumption," Scorsese can take his time. On a Scorsese set, you more than likely will not have to worry about a controversial acting choice or how you will test with an audience, at least not in the same way that the incessantly focus-grouped projects in Hollywood might demand.

This may require an adjustment in how you see your own performance and film itself. It requires a greater vulnerability and the willingness to go to unexplored lengths of human complexity. As an actor, you aren't part of something "manufactured for immediate consumption," but rather, something meant to be savored.