Why Prince Of Darkness Is John Carpenter's Best Movie

No one's getting out of here alive.

It is the crux of most horror movies featuring an ensemble cast, particularly those of John Carpenter. Even with his Halloween and The Thing embedded in the memories of horror movie fans, few films have filled audiences with dread and foreboding the way his 1987 feature Prince of Darkness does. Carpenter has taken every lesson he learned — both as a Hollywood outsider making renegade films and as someone who earned a place within the system — and put it on the screen.

It's a singular vision on display: directed, written (under a pseudonym), co-produced, and as always, featuring a score composed by Carpenter (with collaborator Alan Howarth). It is an effort that shakes off the big-money reliance of previous films. It shows its teeth at every opportunity, and will absolutely take a bite out of you.

But is it Carpenter's best? There's ample evidence to make the case, and it all comes down to the director's singular, gruesome vision of a hopeless world yet to come.

Back to basics

John Carpenter built his career on the foundation of "guerilla" filmmaking, keeping the productions as in-house as possible. That kept locations small, special effects practical, and budgets tight, but it also kept suspense high. Having a small stage kept everything in close range and tight, affording a sense of claustrophobia that promoted the right kind of tension.

Carpenter's fortune opened up in the early 1980s with a string of big-budget efforts: The Thing, Christine, and Starman. But the box office failure of the ambitious Big Trouble in Little China brought Carpenter back to his roots for his next effort, Prince of Darkness. The aim was to gain much more control over all aspects of the process, including writing the project under the pseudonym "Martin Quatermass."

The story takes place primarily in a single church. Inside the basement of the church is a large cylinder of green, swirling liquid, allegedly the essence of Satan himself. Outside, homeless people have been possessed by evil and converge upon the church to keep a small group of scientific researchers and a priest from escaping, while at the same time standing watch for when Satan emerges from containment.

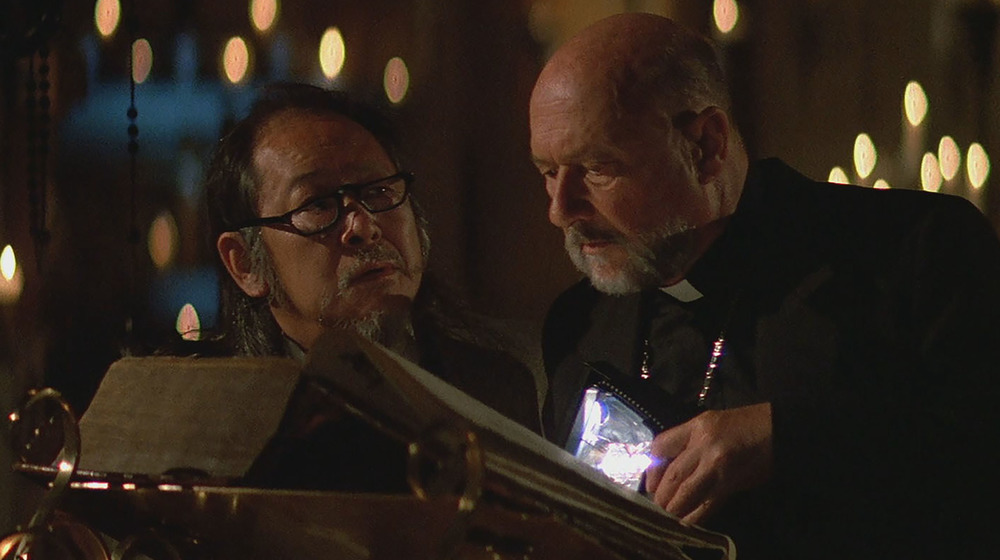

Carpenter used actors primarily from television — several from soap operas — and even cast crew members. Special effects coordinator Robert Grasmere played Frank Wyndham, who was stabbed to death by a homeless woman, reanimated, and then had his zombie corpse consumed by bugs.

What is the Apocalypse Trilogy?

Prince of Darkness is considered the second installment in what John Carpenter calls his "Apocalypse Trilogy," a loose collective which also include The Thing and In the Mouth of Madness. Each movie focuses on a scenario depicting how the end of the world begins, and in Carpenter's hands, it's not from a nuclear bomb blast, but from a smaller incursion of evil that spirals out of control.

In each of Carpenter's films, either in the trilogy or not, there are few traditional happy endings. Carpenter's finales are regularly downbeat and often suggest that evil wins in the end. This is even more true of the Apocalypse Trilogy, each of which ends on an ambiguous, ominous note.

In Prince of Darkness, researcher Brian Marsh (Jameson Parker) is haunted by nightmares of lo-fi video recordings purporting to be from the year 1999. They show the outside of the church the scientific study team is working in. The videos claim to capture the rise of the Anti-Christ (or in this film, the "Anti-God"), once trapped in the antimatter of quantum space, but now free to herald the end of humanity. Although it seemed the last surviving member of the research team succeeded in stopping the Anti-God's emergence, the last video transmission shows that the only change is whose body would be taken over as host for the literal "prince of darkness."

Making a silly premise terrifying

Prince of Darkness is built around a premise that, on paper, seems ridiculous. In short, there is a cylindrical vessel in the basement of a church that is purportedly a prison for the essence of ultimate evil. It's a giant jug of liquid Satan, looking like a backlit Ecto Cooler. But it becomes horrific through Carpenter's building of suspense.

Had the story dwelled on this, no one would think about the film at all more than 30 years later. The key to success is personification, making the story less about the liquid in the giant jug and more about the prevalent evil animating it, along with the zombified street people outside of the church. The evil is everywhere: in the minions outside keeping the protagonists trapped within; inside the church, dripping from the container and spraying onto the walls and ceiling in defiance of physics; and inside the researchers themselves as they are forced to ingest the devil-spray.

Mirrors become portals into a fluid quantum realm, the actual prison of the Anti-God. At every turn, Carpenter takes something you know from daily life and makes you question how safe it really is. That ability to subvert these norms and turn them into threats instills a dread across the entire film.

Building tension through containment

Prince of Darkness' tension is, at heart, based on claustrophobia. It is a long-utilized tool in haunted house stories, yet one that ends up being a difficult plot point to rationalize. Stuck in a haunted house? Why not just leave the house? End of story.

What John Carpenter achieves with this story is that the hope of escape is removed from the characters' options. Much like The Thing, there really is no escape.

Carpenter doesn't make scenery excessively tight or unnaturally dark, as so many other haunted-house-type stories do to achieve the same results. Instead, rooms are filled with cast members nearly tripping over each other. Narrow streets are ever more constricted by silent, lumbering zombies who, at a second's notice, break into murderous sprints. In fact, one starts to realize the most dangerous moments aren't when one is alone in the darkness of a tiny space, but when they're out in the open and fully exposed. It's no surprise that the dread-suffused story would have a profound (if temporary) psychological effect on those watching it.

A mix of old and new players

Actors in the United States have greater options now than they did in the 1980s. Back then, the divisions between "film actor," "stage actor," and "television actor" were clear, and so were the price tags for their services. Having a cast full of affordable, recognizable faces could only be a benefit for John Carpenter as he maniacally picked off characters during Prince of Darkness.

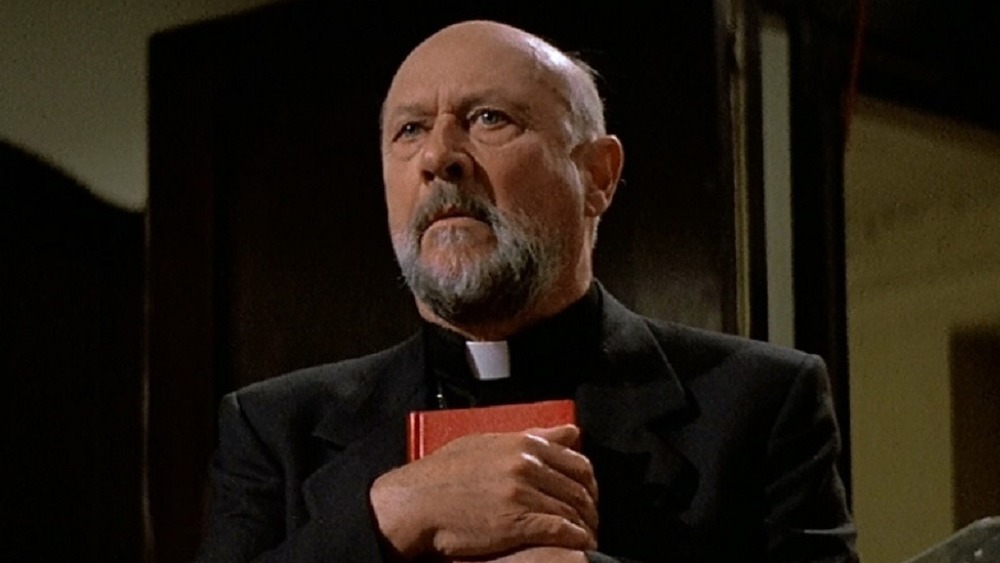

At the top of the credits are actors Jameson Parker (Simon & Simon), Susan Blanchard (All My Children), Anne Howard (Another World, Days of Our Lives), and Thom Bray (Riptide). Dirk Blocker, currently part of the cast of Brooklyn Nine-Nine, was also featured. Joining these actors — all new to the Carpenter stable — were old favorites such as Donald Pleasance (Halloween, Escape From New York), Victor Wong and Dennis Dun (both from Big Trouble in Little China). The film also included veteran shock rocker Alice Cooper in a memorable role as a silent, murderous street person.

Another benefit of having a large cast of television actors was that Carpenter was utilizing a roster well versed in working quickly, generating the most out of 30 days of shooting. Further, having recognizable faces that aren't marquee names meant one could never count on their character's survival. If you cast Bruce Willis, you can't justify his cost and also kill off his character midway through, not in the way Alice Cooper uses a broken bicycle to impale Thom Bray's character.

Live, undead, and in-camera

John Carpenter wanted all the gruesome, unsettling special effects of Prince of Darkness to be achieved "in-camera." There were two reasons: post-production effects cost a lot and Prince of Darkness was designed to be lean and mean. Plus, effects done for real give the actors something to react to, and given the horrific nature of the story, getting genuine responses was only going to benefit that deep, chilling dread Carpenter was aiming for.

In the documentary accompanying the film's Blu-ray release, special effects coordinator Robert Grasmere, who also played Frank Wyndham in the film, described how his character was consumed by bugs. Close-ups presented Grasmere with desiccated face makeup, black contact lenses, and dental veneers to mimic rot. Long shots had a dummy rigged with collapsing tubes so that, as fake limbs dropped away, bugs would spill out of now-empty sleeves, the body would crumple to the ground in stages, and would eventually be swarmed by even more bugs.

In another disturbing scene, the effects crew used a false frame filled with mercury to achieve the effect of hands reaching into the mirror-portals. Another scene has Donald Pleasance's priest swing an axe at Kelly (Susan Blanchard), now the host of a demonic force, cutting off her arm. Another one emerges to replace it. Then he beheads her and she simply picks the head up off the floor, leaving traces of gooey blood behind, and reattaches it.

A propulsive synthwave score

While iconic now, Carpenter's synthwave scores for his movies were strictly a cost-savings function. In most productions, the score is the last expense filmmakers focus on, so these are typically worked out when significant amounts of the budget have already been spent. Carpenter recounted for the website Screenrant how he made the decision to give Halloween its now classic score. Since then, his music has become synonymous with his features, and Carpenter lays it on for Prince of Darkness, with cacophonous key-punches to punctuate jump scares alongside chilly digital choirs.

To say Carpenter's music has been influential is an understatement. Synthetic, minimalistic music became a go-to for science fiction and horror films in the late '70s and '80s for the same reason that Carpenter described: it's cheaper that way. But in the effort to economize, the sound became an aesthetic. James Cameron might not have hired Brad Fiedel for both Terminator and Terminator 2: Judgment Day without this, nor might the Duffer Brothers have thought synthwave to be the right sound for the Stranger Things theme without his influence.

In recent years, Carpenter has left filmmaking behind and focused primarily on writing and recording music, releasing them as his series of Lost Themes albums on the Sacred Bones record label.

Who was that out on the street?

John Carpenter met Alice Cooper for the first time at Wrestlemania 3 in 1987. Cooper's manager Shep Gordon was getting into film production and would be behind not only Prince of Darkness, but Carpenter's next film, They Live, featuring WWE superstar "Rowdy" Roddy Piper.

According to the documentary accompanying the film's Blu-ray edition, Carpenter asked Cooper to make a cameo in the film as one of the crowd of possessed street minions. This quickly changed from a wink at the audience — which in retrospect might have been a false note that could have negatively disrupted the film — to making Cooper the leader of the homeless damned. After all, if you are going to have a menacing stranger, possessed by evil, trapping doomed scientists inside a haunted church, who better to play that stranger than Alice Cooper?

Cooper praised the choice of having the mob be silent. They are puppets of demonic forces and are in place solely to keep the researchers trapped inside the besieged church. One of these, maybe more, will be the physical host for the Anti-God in this world and it is the zombie horde's mindless mission to keep them there. Cooper noted that having them be anything but deathly quiet would have broken the tension.

Was this the start of found footage horror?

A pivotal element of Prince of Darkness is the grainy videotape footage beamed back from the future, documenting the coming of the Anti-God and heralding mankind's doom. The videos remind the audience from time to time that the history has already been written and we are just witnesses to the downfall. This in turn fortifies the prevailing dread as the titular prince of darkness inches closer to its goal.

The videos further embed in the viewer's psyche the notion that while film can lie to you — through calculated cuts, special effects, and well-placed music — video doesn't. Video is documentary, especially when the shaky image clearly looks like it is shot by an amateur. The juxtaposition between this and the carefully composed film cinematography sets the viewer on edge. It's another subversion of norms.

In 1999, the makers of The Blair Witch Project would fully exploit the presumed veracity of video for thrills and chills. Later on, the almost accidental narratives of security cameras in the Saw and Paranormal Activity films would drain the found-footage trope of every last drop of blood.

Audiences might not have known how to process those clips in Prince of Darkness, watching what seemed like a disconnected storyline suddenly becoming the raison d'etre for the whole story. Nonetheless, its impact on future horror filmmakers can't be ignored.

A lasting impression

With its underdog status, audiences do not expect much from Prince of Darkness, which sets them up for a sense of dread that lingers long after the movie is over. After all, the film is caught in the shadow of its filmmaker's own iconic Halloween, and when the conversation swings around to "which Carpenter movie scares you most," people will reflexively think of that legendary movie. A sleeper movie like Prince of Darkness that hangs so low on the family tree can't possibly have much shock and horror to bear, right? That underestimation has only benefited the movie, especially in its era of home video where younger viewers could watch in the comfort of their own home.

In the documentary found on the Blu-ray, Carpenter cited Jean Cocteau as a major influence for the movie's feel. Not surprisingly, so did director Herk Harvey when discussing his Carnival of Souls (1962), also a horror film suffused with dark moodiness, and also a movie that creeps into the consciousness of the viewer when the last reel is done. Like Carnival of Souls, Prince of Darkness was made on a shoestring and couldn't cheat on tone with a multi-million dollar special effects budget. Both films had to latch onto the subconscious of the viewer, and both films succeed in disturbing the watcher.

How does it rank in Carpenter's filmography?

While not a box office barnstormer, Prince of Darkness has grown a considerable cult following thanks to home video. Among general movie fans, it often trails John Carpenter's more recognized titles, like Halloween, Escape From New York, and The Thing. Yet among his most ardent devotees, the movie occupies a special, rarified place.

Much of this comes from the realization that Prince of Darkness is a master thesis that could only have been made after The Thing. The lessons of how long a camera can linger on a character to reveal hidden motivation before cutting away have been internalized. Knowing how grotesque one can go before the moviegoer checks out is key. The spookiest thing isn't necessarily the giant vat of liquid Satan, but the secrets lurking behind one's own mirror or underneath one's own skin.

At the same time, this movie rejects lessons that big Hollywood productions regularly inflict on distinctive filmmakers. Carpenter must have known that if it couldn't be accomplished on-site and on budget, no amount of post-production effects, jump-cut edits, and sound-fixing would resurrect it. Prince of Darkness had to be made guerilla-style, lean and mean, with the spirit of an independent filmmaker without deep budgetary pockets to fall back on.

The movie exudes the fearlessness of a filmmaking newcomer while applying the deft hand of a veteran who knows what he wants and how to get it on the screen.