Why RoboCop Is The Sci-Fi Film Most Representative Of The 1980s

The 1980s was a golden age for cinematic science fiction. George Lucas had whetted the appetite of a new generation with the visual extravaganza of Star Wars and its sequels, while showing Hollywood that sci-fi could headline a new era of studio blockbusters. Steven Spielberg got in on the act with his brand of warm and fuzzy sci-fi — epitomized by E.T. (1982), which paved the way for heartwarming sci-fi such as Back to the Future (1985) and Cocoon (1985). Even gross-out sci-fi-horror master John Carpenter got in on the trend with 1984's endearing Starman.

'80s cinema also featured a dark strain of R-rated science fiction that dramatized serious themes of the era, such as transhumanism, artificial intelligence, first contact, dystopia, and technology run amok. These movies took advantage of advancements in prosthetic makeup and practical effects to render their bleak visions with gore and ultraviolence. Examples include Blade Runner (1982), The Thing (1982), The Terminator (1984), and The Fly (1986).

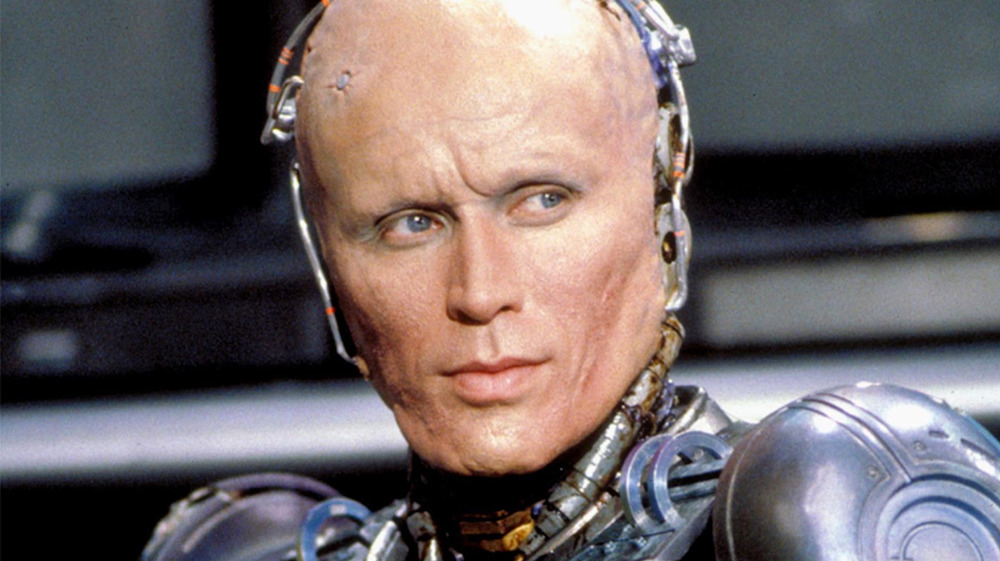

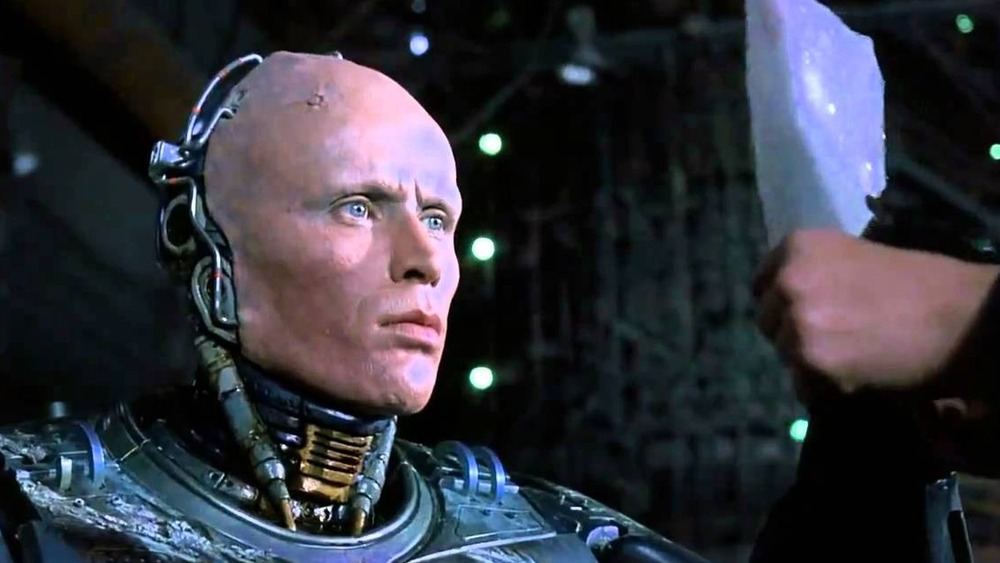

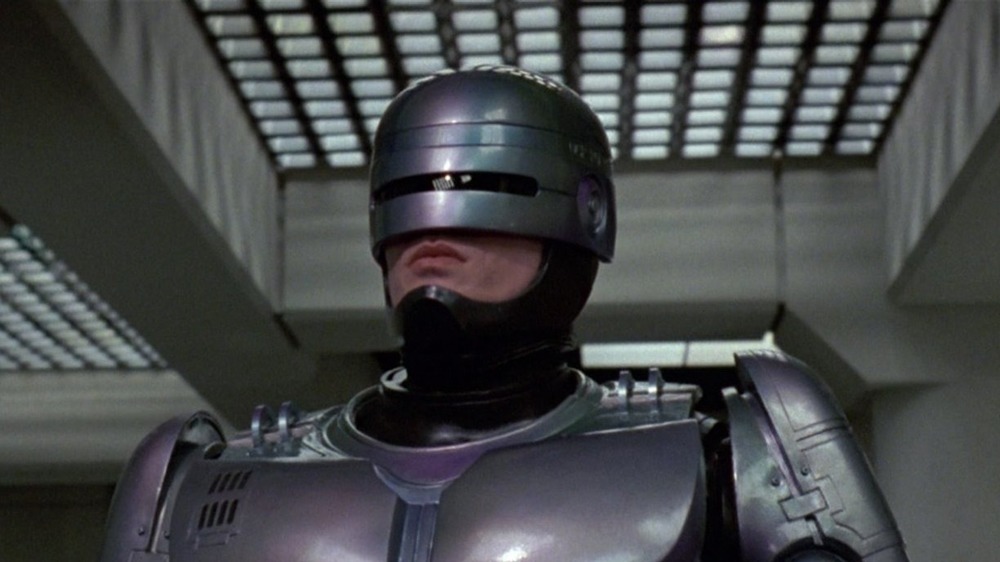

Paul Verhoeven's 1987 classic RoboCop exemplifies '80s sci-fi by fusing these approaches. Its vision is dark and hyperviolent, but also tenderhearted. Like many of its contemporaries, the movie — about a cyborg cop struggling to remember his identity as he takes down a network of nasty criminals — is a cautionary tale of the excesses and obsessions of its era. It's also a wickedly funny satire of the Reagan decade. Here's a closer look at the ways in which RoboCop is the most representative sci-fi film of the 1980s.

It's a buddy cop movie

One of the most popular subgenres of '80s movies was the buddy cop film. Two partners are thrown together, bicker and clash, learn to trust each other, and finally become a formidable team. Audiences couldn't seem to get enough of all the wisecracks, shoot-outs, and car chases in Beverly Hills Cop (1984), Lethal Weapon (1987), Red Heat (1988), Dragnet (1987), Stakeout (1987), Tango and Cash (1989), and many others.

RoboCop both follows and subverts the formula. Alex Murphy (Peter Weller) gets transferred from his cushy uptown station to the urban hell of Old Detroit. He partners with the veteran Anne Lewis (Nancy Allen), who is initially put off by Murphy's cockiness — standard buddy cop stuff. RoboCop departs from the formula by making one of the partners female. Another major difference is that Murphy is shot to death on their first day of work together. Lewis disappears for a stretch while Murphy's consciousness is implanted into RoboCop, but once she recognizes him, they reunite to take down the bad guys that killed him.

Buddy cop movies of the era had little use for female characters, who served as background to the bromance between the male partners. Lewis' competence and professionalism as a police officer, as well as the fact that she is never sexualized or made into a love interest, is one of the many ways that RoboCop was forward-looking while still embracing '80s conventions.

It features ultraviolence

The Motion Picture Production code, which forbade the presentation of graphic violence, was lifted in 1968 in favor of the movie rating system. Hollywood — which had long chafed at the restrictions, pushing the boundaries with films like Bonnie and Clyde (1967) — responded immediately. No longer did the shooting victim simply clutch his chest and fall from his horse. Now films like The Godfather (1972) showed the bloody damage those bullets could do. But it was the sci-fi and horror films of the late '70s and '80s that took full advantage of this new freedom (along with major advancements in visual effects makeup and prosthetics) to shock and horrify audiences with graphic violence and gore.

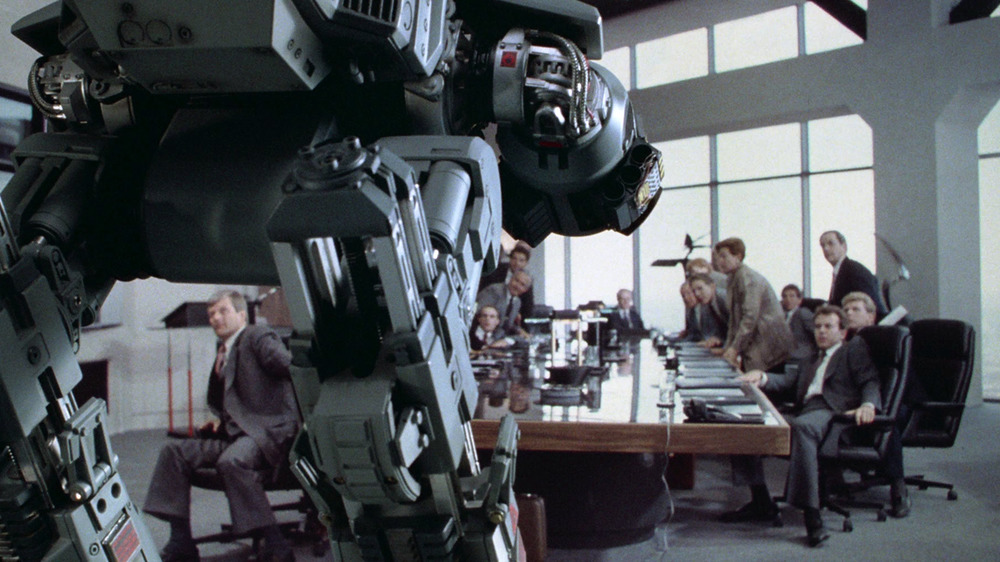

RoboCop was fully on board, but not just for exploitation or titillation. The extreme violence conveys a brutal future in which human life isn't valued. For example, Omni Consumer Products (OCP), the corporation that builds RoboCop, hopes to use mortally wounded cops in its Frankenstein-like experiments. Early in the film, when prototype robot ED 209 malfunctions during a demonstration and guns down a junior executive, the CEO says only, "I'm very disappointed." The dead man is an afterthought. The scene became famous partly because Verhoeven originally wanted the character shredded into hamburger (using 200 squibs, a record at the time) to show the thoughtless cruelty of weapons technology unguided by human judgment. The filmmakers were forced to cut the scene to achieve an R rating, but you can find Verhoeven's original vision in all its bloody glory on Blu-ray.

It shares — and satirizes — '80s gun obsession

The military-industrial complex and the ultraviolence that often accompanies it need plenty of firepower. '80s movies were obsessed with firearms — the bigger, the better. Some critics suggested that Americans were trying to regain a sense of national strength after losing the war in Vietnam by filling screens with beefed-up superheroes like Arnold Schwarzenegger, Sylvester Stallone, and Chuck Norris wielding massive military-grade weapons (often with one hand). Science fiction movies got in on the act as well. The Terminator, Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior (1981), Predator (1987), even Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (1982), were bloody affairs loaded with guns, while Aliens (1986) was basically a war movie set in space.

Like its contemporaries, RoboCop features wall-to-wall firearms. However, it's more conscientious and subtly critical of America's gun fetish than other films of the era. Early in the film, the pre-RoboCop Murphy practices spinning his gun into his holster because of a TV show he saw. Later, when the villainous Boddicker gang acquires assault cannons, they blow up half a city block, cackling with glee like 12-year-olds. RoboCop himself is equipped with a machine gun pistol that he uses in several firefights, including when he blows away dozens of goons at a cocaine processing factory. Later, cops use thousands of rounds trying to take him down. As Boddicker, quivering with excitement, exclaims in one meta moment, "Oooohhh, guns, guns, guns!" The obsession with guns is so extreme that it becomes satirical.

It condemns the military industrial complex

The way that the Vietnam War was covered in the press — especially on television — changed everything about the way Americans viewed the United States. The bloody images, the traumatized soldiers, and the bombing of civilians could no longer be concealed the way it had been in World War II. Americans were sick of war, and protested against it in record numbers in the 1970s. Even after the war in Vietnam ended in 1975, Americans held demonstrations against nuclear proliferation and war generally in the 1980s. Still, President Reagan doubled down on the military-industrial complex, increasing contracts with private corporations that charged taxpayers astronomical prices for elaborate weapons systems.

RoboCop condemns these giant corporations for fleecing taxpayers and operating without any meaningful public oversight. In the movie, OCP has privatized the Detroit police, but not to the advantage of the cops, who desperately need resources. As the opening scene shows with grim hilarity, whether expensive weapons systems like ED 209 function is beside the point. Says OCP corporate villain Dick Jones (Ronny Cox), "I had a guaranteed military sale with ED 209! Renovation program! Spare parts for 25 years! Who cares if it worked or not!" Later, when Jones enlists the movie's other bad guy, Clarence Boddicker (Kurtwood Smith), to destroy RoboCop, Boddicker asks Jones if OCP has access to military weaponry. With a smirk, Jones answers, "We practically are the military." (Sidenote: Cox and Smith give two of the all-time greatest bad guy performances in this movie.)

It's a savage critique of capitalism

RoboCop is such a blistering takedown of the hypocrisy and dehumanization of 1980s capitalism that it seems almost unbelievable that it even got made. Maybe because the other major anticapitalist flick that year, Oliver Stone's Wall Street (1987), got all the attention. Maybe it's because Verhoeven skillfully wove his themes within such a fast-paced and thrilling story that people were slow to notice. Or maybe the exploding heads (understandably) distracted from the deeper meaning. But esteem for the movie has grown in the intervening decades, with many critics and writers praising its scathing indictment of free enterprise.

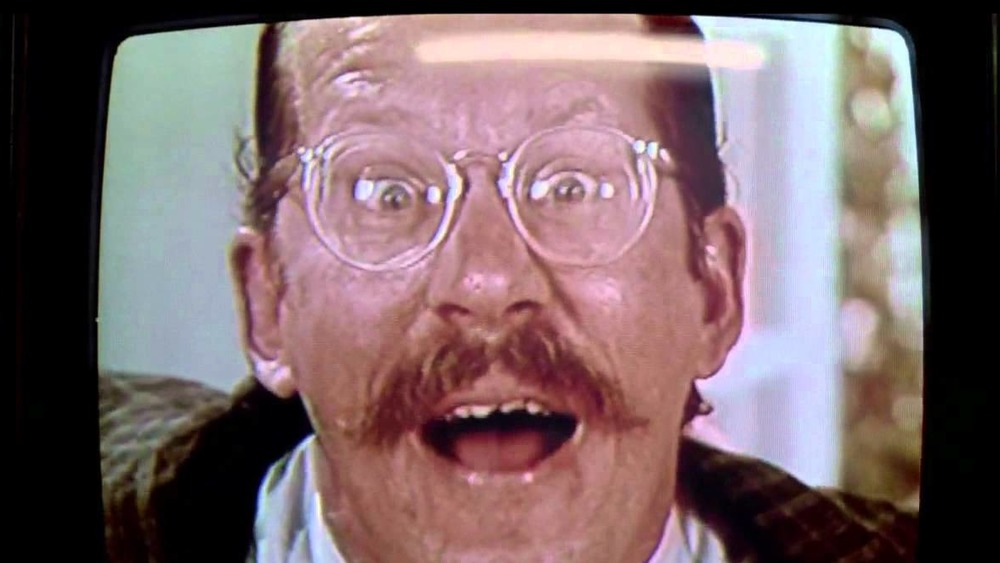

The fact that Verhoeven was Dutch and new to making American movies might have given him a more objective and distanced view of U.S. capitalism's excess and contradictions. Among his many targets is American television. RoboCop includes a series of fake commercials seen during Detroit newscasts. These ads feature such products as "Nuke 'em," a Battleship-style game in which family members annihilate each other's armies in poofs of mushroom clouds. People in Old Detroit also watch the idiotic TV program I'll Buy That for a Dollar, a cross between a game show and a Jerry Springer-type talk show with a leering host who paws scantily clad models. It's not exactly clear what is being sold for a dollar on the show. The commercials indict the shamelessness of American television, which makes everything for sale — even nuclear holocaust.

Cocaine!

The 1980s was the material decade. It was also a decade when Americans loved to party it up with cocaine. Unfortunately, drugs are bad (mkay), at least according to the U.S. government, which started a war on them. Hollywood has long used real U.S. enemies as fictional villains (Nazis, Soviets, etc.), and drug dealers were no different. Many '80s onscreen bad guys were coke dealers, including those in Scarface (1983), Beverly Hills Cop, License to Kill (1989), and TV's Miami Vice.

RoboCop embodies the tradition. Drugs are just one of the many rackets that Boddicker's gang is involved in. The shootout at the cocaine factory, with billowing clouds of white powder everywhere, lets the viewer vicariously experience the righteous fun of blowing scumbag dealers away. The higher-class crooks are coke enthusiasts, too. When OCP executive Bob Morton (Miguel Ferrer) entertains several guests, there's so much coke on the table it looks like a snow globe exploded. But while the movie associates drugs with villainy, it also considers illegal drugs to be just one more cog in the capitalist enterprise. When Jones asks Boddicker to kill RoboCop, one of the carrots he dangles is control of the drug trade in the soon-to-be constructed Delta City. It's "virgin territory for the man who knows how to open up new markets," Jones tells Boddicker, framing it as a business opportunity akin to military contracting. Showing that players in the capitalist system are willing to do anything to maximize profits illuminates the hypocrisy of the system.

Themes of transhumanism and artificial intelligence

Transhumanism — the idea that human beings can be "enhanced" by technology — and artificial intelligence have been staples of science fiction almost from the genre's beginning. But the quantum leap in computing in the 1980s led to renewed concern about how technology would transform and even eclipse man. WarGames (1983) presents an AI computer that threatens the world with thermonuclear war until it teaches itself that a war of that sort is unwinnable. The Terminator imagined a scenario when robots "wake up" and decide to dispense with humanity. Blade Runner featured replicants — "more human than human" androids — who can reason, feel, and develop their own goals and desires.

Like most of the films that address these themes, RoboCop emphasizes the importance of the cyborg's human side, which has judgment, wisdom, intuition, and compassion. The film contrasts RoboCop — who possesses these qualities — with the intelligent but inhuman robot, ED 209, which is programmed to kill, but has no inherent mercy or reason that might prevent it from, say, obliterating an executive in a boardroom. During a showdown with RoboCop, ED 209 shows itself incapable of navigating a set of stairs. It tumbles down onto its back, immobilized, and starts to kick and scream like a toddler. This moment pointedly shows that artificial intelligence is still in its infancy.

It has fun with the '80s toxic waste obsession

The 1980s were characterized by excessive angst over the threat of nuclear war, dramatized in many movies of the era. Innovations in makeup and visual effects let filmmakers more realistically depict the hideous effects of nuclear winter and radiation poisoning in movies like The Day After (1983), Testament (1983), and even Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (Spock succumbs to radiation sickness and the Enterprise barely survives a nuclear-style explosion). This fear of nuclear power, as well new environmental threats such as acid rain and ozone depletion, manifested itself in '80s movies' obsession with toxic waste (invariably stored in vats, as seen in the instant classic Rick and Morty homage, The Vat of Acid Episode) and yielded some gnarly gross-out effects, usually in low-budget affairs such as The Being (1983) and cult classic The Toxic Avenger (1984).

RoboCop has fun with the tradition during the movie's climax, which is set at an abandoned industrial site in Old Detroit. During a chase, one of the bad guys crashes a van into a huge vat helpfully labeled "Danger: Toxic Waste," then emerges in a nasty, steaming soup. He survives the noxious deluge, but not without the flesh sloughing off his hands and face in slimy folds. The pièce de résistance comes a moment later, when he trundles his toxic zombie ass into the path of a speeding car and explodes like a bag of rotten cantaloupes.

Fading industrialism

Blue-collar jobs in industries like steel and manufacturing were disappearing by the 1980s. The Rust Belt was oxidizing, ending the days of high-wage, low-skill opportunities. Meanwhile, the popularity of Japanese cars in the United States was eclipsing the domestic auto industry, closing plants and forcing layoffs. Detroit was at the center of all this, so it made sense to set RoboCop in "Old Detroit" as a symbol for American decline. The decades since have been characterized by ever-widening wealth gaps. RoboCop — like Blade Runner a few years earlier — is unsparing in its grim vision of a future with a few haves and many have-nots.

Like the corporate titan Eldon Tyrell in Blade Runner, the OCP execs lord over their city from a 100-story glass and steel tower. They aim to replace Old Detroit with Delta City, an ostensibly utopian metropolis that will be entirely privatized (like much of America today). RoboCop, however, is born out of Old Detroit. Murphy is a cop who protects his city. The part of him that's still human and sympathetic to the denizens of Old Detroit resists becoming a corporate pawn and a private policeman for the rich. Maybe that's why the real Detroit commissioned a bronze statue of their fictional protector.

Special effects makeup

The 1980s were the last great years of practical visual effects, before Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991) and Jurassic Park (1993) demonstrated the power of CGI. There's no doubt that the best CGI effects can create seamless, elaborate, and lifelike worlds. But there's something incredibly charming about the practical effects and prosthetic makeup of the decade of cute aliens, scary robots, and gross monsters. These handmade effects possess more personality. That's certainly true of RoboCop, which features the terrific work of pioneering effects artists Rob Bottin and Phil Tippett.

A movie about robots and cyborgs ultimately lives and dies on the strength of its robots and cyborgs. They must be unique and feel integrated into the overall look of the movie. In this, RoboCop was a huge success. Bottin had done sophisticated makeup work in a number of notable films, including The Howling (1981) and The Thing before he designed and built RoboCop's suit. Tippet, meanwhile, had done stop motion and miniature and optical effects work on A New Hope (1977) and The Empire Strikes Back (1980) before being recruited to design and do stop-motion animation for ED 209.

'80s sci-fi was characterized by multitudes of monsters, aliens, robots, and cyborgs. RoboCop's additions to the pantheon proved to be among the most memorable. That's one of the many reasons the movie is the quintessential 1980s flick.