The Weird Old West: Horror And Fantasy-Themed Westerns

At its heart, the Western is about bringing "civilization" to uncharted and untamed territory. Most movies that fall under that genre show us that strength, determination, and a strong moral code turned the frontier into a paradise for white settlers (superior firepower certainly helped, too). What's not addressed (or rarely addressed, especially in classic Hollywood Westerns) is that the rush for Manifest Destiny and its promised opportunities also forced pioneers to face brutal conditions and people with very different ideas about turning over their ancestral lands.

Revisionist Westerns like Little Big Man and modern efforts like Dances With Wolves show the ugly and unjust sides of how the West was won. There's also a subgenre of Western films with horror and fantasy trimmings (as well as a few defying any classification) that graphically illustrate the perils that awaited the unwary cowboy or ambitious settler putting down roots in a wild territory. Following are some of the weirdest, wildest Westerns on film. Saddle up, partner –- the trail gets dark from here.

This list doesn't include horror or fantasy films with a Western "feel," like John Carpenter's Vampires and Near Dark, or ones that take place in Western settings, like The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and The Hills Have Eyes. The movies discussed are mostly traditional Westerns that take place in the American West during the late 19th or early 20th century. Expect horses, six-guns, and ten-gallon hats.

Note: Spoilers will follow.

A vampire stalks the West in Curse of the Undead

Think of the term "vampire Western," and chances are, your mind will either turn to B-grade horror movies set in the Old West (the ridiculous Billy the Kid vs. Dracula) or modern-day chillers with Western trappings, like Quentin Tarantino's From Dusk to Dawn. Somewhere between those two poles is 1959's Curse of the Undead, a supernatural Western from Universal's budget subsidiary, Universal-International.

The premise is textbook for both genres: Strange deaths in a small Western town are traced back to a mysterious stranger, Drake Robey (played by Australian actor Michael Pate). Once the black sheep of a wealthy Mexican family, Robey long ago murdered his brother and committed suicide before turning undead. Robey's vampire origin story is the most unique thing about this modest black-and-white creepshow. It's suicide, not another vampire, that causes his transformation –- a variation taken directly from English folklore. Since Robey isn't a traditional bloodsucker, other established vampire tropes don't apply to him. He can't be destroyed by sunlight, so veteran low-budget movie writers Edward and Mildred Dein have him killed with a bullet, a thorn, and a cross.

Django Kill: the spaghetti Western on acid

There are two things to know about 1967's Italian-Spanish Western Django Kill... If You Live, Shoot! First, not one of the characters is named Django –- the mention is a bait-and-switch reference to Sergio Corbucci's Django, designed to lure in ticket buyers. Second, you've probably never seen anything like it.

Tomas Milian (Traffic) stars as the Stranger, a former bandit who may or may not be undead (he's first seen crawling out of a mass grave). The Stranger sets out to get even with his double-crossing ex-partner and runs afoul of "The Unhappy Place," a town seemingly populated by lunatics and overseen by a sadistic boss and his jackbooted henchmen. Director Giulio Questi pitches his film somewhere between a surrealist exercise and a splatter film. Villains are shot with gold bullets, corpses are torn apart by the deranged townspeople, and a horse is blown up. There's a mass lynching, a crucifixion, torture with lizards and bats, and two people are burnt alive after being covered with molten gold. Add to that unholy mix a barrage of flashbacks and frenzied edits, and you have what's most likely the first psychedelic spaghetti Western.

Cowboys vs. dinosaurs in The Valley of Gwangi

Special effects legend Willis O'Brien, who created the stop-motion animation for 1933's King Kong, originally conceived the story for 1969's The Valley of Gwangi, about cowboys who travel to Mexico to capture a living Allosaurus for their Wild West rodeo show. Seven years after O'Brien's death in 1962, another FX pioneer, Ray Harryhausen, brought Gwangi to life in his final animation effort featuring dinosaurs (his other show-stopping Jurassic work can be seen in Mysterious Island and One Million, B.C.).

The movie itself is a minor mix of Western action and fantasy material with a dash of romance, but Harryhausen's creatures are, as always, top-notch. In addition to the titular Gwangi (which looks more like a T-rex than an Allosaurus), he also crafted and animated a Pteranodon, a horned Styracosaurus, and a delicate, horse-like animal known as an Eohippus. The scenes of the cowpokes lassoing Gwangi are impressive feats of editing live-action and animation footage. Harryhausen brings down the house — literally –- in a finale that pits the creature against the film's heroes in a burning cathedral.

The Western gets mystical in El Topo

El Topo is a Western in the same way that, say, Donnie Darko is a coming-of-age story and Eraserhead is a horror flick. These movies borrow a few of the genre's trappings and tropes, but they are wholly original creatures.

El Topo is about a gunman (played by the film's writer/director, Alejandro Jodorowsky) who defeats a trio of master gunfighters before undergoing a sort of death and rebirth. Describing the film that way paves over the sometimes impenetrable layers of religion and mysticism woven into the film, which portrays El Topo as a sort of hippie Christ. It also ignores the barrage of strange and disturbing imagery that Jodorowsky hurls at the viewer, from people with extreme physical disabilities to whip battles, rivers of blood in the streets, children playing a game of Russian roulette, rabbits, and swarms of bees (lots of bees).

El Topo's sensory overload and spiritual/magical elements made it a favorite among the hippest members of the counterculture, including John Lennon and Yoko Ono, who convinced The Beatles' manager, Allen Klein, to buy the rights for theatrical release. A lengthy run at New York's Elgin Theater in 1970 helped create the "midnight movie" phenomenon.

Bikers meet witches in Hex

Arguably the most obscure film on this list, 1973's Hex is also one of the strangest. A hazy mix of folk horror (before such a thing existed), Western, biker film, and hippie mysticism, Hex stars Keith Carradine, Scott Glenn, and Gary Busey as motorcyclists crossing the U.S. after World War I. A detour into a small Nebraskan town puts them literally in the crosshairs of the locals. They find refuge on a farm owned by two orphaned sisters (Hilarie Thompson and Cristina Raines, here billed with her real name, Tina Herazo). The siblings' late father, a Native American shaman, appears to have passed down his supernatural abilities to his children, which spells doom for some of the motorcyclists and a new lease on life for others.

The film's free-wheeling approach to genre –- it careens from suspense to off-kilter humor, from romance to trippy mysticism –- appears to have baffled everyone, including distributor 20th Century Fox, which waited two years before briefly releasing it. But Hex does have some eerie atmosphere, most notably at the girls' farm, which was filmed at the Cheyenne River Indian Reservation in South Dakota.

Clint Eastwood returns from the grave in High Plains Drifter and Pale Rider

Though the horror element in both films is muted, Clint Eastwood's High Plains Drifter, from 1973, and 1985's Pale Rider both involve a supernatural figure handing down vengeance upon the corrupt citizens who caused their deaths.

Eastwood, who directed both films (and also produced Pale Rider), stars in High Plains Drifter as a nameless stranger who deals out death and destruction to the residents of a small town under the thumb of a vicious outlaw (Eastwood regular Geoffrey Lewis). In Pale Rider, he's again nameless, but his clerical collar earns him the name "Preacher" from the downtrodden prospectors working for a cruel mining boss played by Richard Dysart.

The supernatural elements emerge in both films when the villains discover Eastwood's true identity far too late: The stranger and the Preacher are both spirits of murdered men who have returned to avenge their deaths. Both Drifter and Rider are short on dialogue and long on violence, though Rider is a statelier affair and less vicious than Drifter (Eastwood's stranger is as bad, if not worse, than the bandits who killed him). The latter film, with its whippings, lynchings, and high body count, is as close to grindhouse fare as Eastwood ever got.

It's cowboys and Vikings in Get Mean

American actor Tony Anthony brokered an American release for three Italian Westerns he produced and starred in through his friendship with the aforementioned Allen Klein, who, as a major shareholder with MGM, arranged for the studio to issue the films in the U.S. between 1966 and 1975. All three films concerned the Stranger, a spoof of sorts on Clint Eastwood's character from the Sergio Leone's Dollars Trilogy. Few Americans, if any, saw the fourth Stranger film, Get Mean, which slipped in and out of drive-ins in 1975 and didn't get a home video release until 2015.

Get Mean's obscurity is unfortunate because it's completely, hilariously, and deliberately out to lunch in every frame. In this flick, the Stranger appears to travel to an alternate reality, where he escorts a princess back to her castle in Spain, which is somehow under assault by both Vikings and Moors. As usual, much of the humor in Get Mean comes from watching the Stranger take his licks. He's hung upside down and roasted on a spit before deciding to (you guessed it) get mean, which entails single-handedly taking on both the Vikings and the Moors with the help of his four-barreled shotgun.

A film as outrageous as Get Mean is hard to beat, but Anthony certainly tried with his subsequent efforts, which included a 3D Western, Comin' at Ya!, and a berserk Raiders of the Lost Ark carbon copy called Treasure of the Four Crowns.

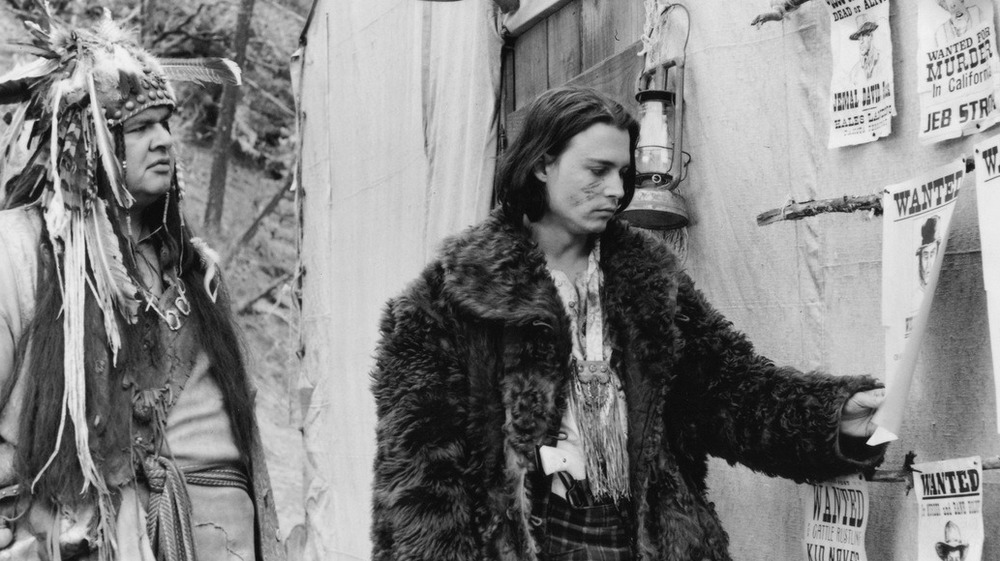

Johnny Depp is a reluctant Dead Man

Johnny Depp plays the title role in Jim Jarmusch's surreal and lyrical Western Dead Man, which offers meditations on spirituality, identity, and society; a haunting, semi-improvised score by Neil Young; and the sight of Iggy Pop in a dress. Depp plays a meek accountant whose job in the remote frontier town of Machine is upended by a series of random violent acts that leave him with a bullet dangerously close to his heart. He is, in a sense, a walking dead man.

His journey with a Native American (Gary Farmer) named Nobody becomes increasingly bizarre and gruesome. Among other unsettling encounters, Depp meets cannibal bounty hunter Lance Henriksen, mountain man Billy Bob Thornton, missionary Alfred Molina, gunman Gibby Haynes (of Butthole Surfers fame), and the aforementioned Iggy Pop. The film is oddly comforting as Depp sheds layers of his "civilized" persona and undergoes a transformation that is oddly beautiful, even if the audience doesn't entirely understand it.

Ravenous bites off more than it can chew

The Native American myth of the wendigo, a monstrous entity created by an act of cannibalism, informs Ravenous, a relentlessly dark and thoroughly unhinged gorefest from British director Antonia Bird (not to be confused with the French-Canadian zombie film of the same name). The plot boils down to a cat-and-mouse game between Guy Pearce and Robert Carlyle. The former plays a disgraced soldier dispatched to a wintry outpost brimming with weirdos (among them such scene-stealers as Jeffrey Jones, Jeremy Davies, and David Arquette), while the latter plays the self-professed sole survivor of a snowbound wagon train whose members resorted to cannibalism.

Carlyle is, of course, spinning a tall tale in order to catch Pearce and his fellow soldiers off guard and then consume them. Once Pearce gets caught up in the flesh-eating business, the picture descends into a grisly mess involving revived corpses, bloody fights, and a very big bear trap. Beloved in certain circles for its streak of dark humor and Carlyle's nuclear-strength overacting, Ravenous is a splatter film that falls short of its arthouse aspirations.

Dig deep into the terror of The Burrowers

You probably missed The Burrowers, a very effective indie creature feature from 2008.

In this flick, a motley band of Dakota Territory settlers goes after a family believed to have been kidnapped by a Native American tribe. The truth behind the disappearance is far more awful in this thriller from writer/director J.T. Petty, who invests as much time in atmosphere and character as he does in the gruesome special effects. A solid cast of character players delivers his spare and thoughtful dialogue, including the always-dependable Clancy Brown and William Mapother as two settlers unprepared for the horrors at the heart of their search.

The Burrowers gets the look and tone of a classic Western right, while also delivering a frightening monster movie and a pointed message about the perils of intruding on land owned by someone — or something — else.

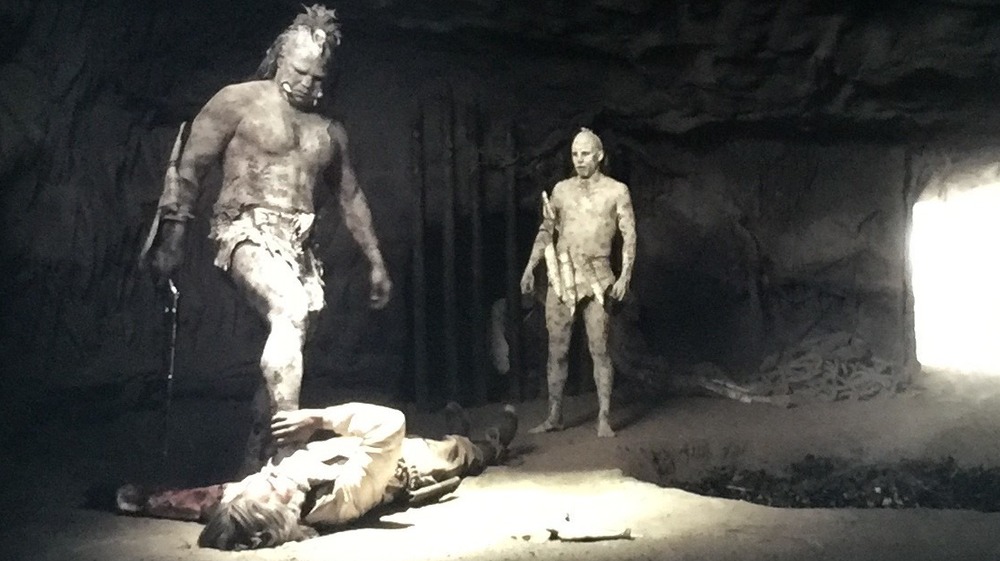

Six-guns and slaughter in Bone Tomahawk

Writer/director S. Craig Zahler surprised critics and audiences with Bone Tomahawk, his feature debut. On paper, the film looks like classic grindhouse fare — a posse pursues a brutal tribe of cannibals. But it's actually a taut Western with an impressive cast of high-profile actors, including Kurt Russell, Patrick Wilson (The Conjuring), and Richard Jenkins (and David Arquette, once again facing off against Old West flesh-eaters).

Such a mix of extremes shouldn't work, but Zahler –- a novelist and former metal musician –- delivers on both the horror and drama fronts. The dialogue is crisp and quotable, and the characters are memorable (Jenkins' eccentric philosopher-fool deputy is a standout). Plus, there are plenty of grisly deaths, including a ghastly sequence that should freeze the blood of even the most seasoned gorehound. Zahler skillfully weaves both genres together, pleasing fright fans and horse opera fanatics alike.

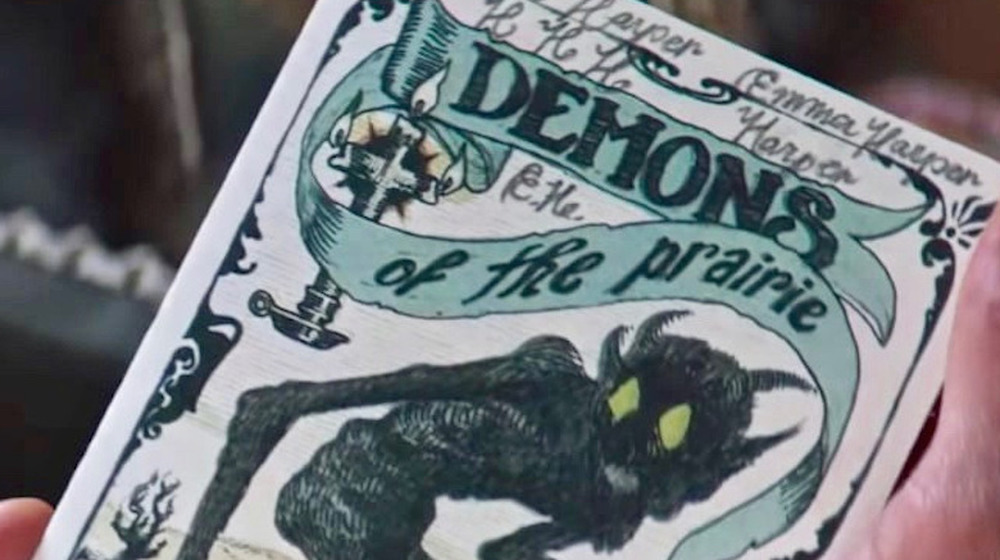

The subtle supernatural chills of The WInd

Horror movies and Westerns that focus on fully developed female characters are rarities. Written and directed by women (Emma Tammi, in her feature debut, and Teresa Sutherland), The Wind offers a refreshing perspective on both genres, as well as some very creepy moments that highlight the dark paths down which loneliness takes us.

Caitlin Gerard (Insidious: The Last Key) and Julia Goldani Telles play two women struggling with their new lives as homesteaders in a remote corner of New Mexico. Their living situation is extremely isolated; their homes are miles from any other people, and their husbands (Ashley Zukerman and Dylan McTee) are inconstant or combative. The prolonged seclusion unmoors both women. Telles goes completely and tragically unglued, and long-simmering tensions turn sinister and terrifying for Gerard.

The truth about who –- or what –- is haunting this homestead remains ambiguous, which only adds to the film's suffocating, eerie atmosphere. The Wind showcases all the hidden dangers of the dusty, lonely stretches of land that occupy huge portions of the U.S.