Things Only Adults Notice In 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea

Disney released Richard Fleischer's 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea in 1954, and the film has had a following ever since. It was critically acclaimed at the time, with its underwater photography, special effects, and art design singled out for particular praise and two Academy Awards. Those technological elements still hold up, and the performances hold up even better.

Fleischer assembled an all-star cast, including James Mason, Kirk Douglas, Paul Lukas, and Peter Lorre. The charismatic ensemble is full of both sparks and gravitas. Literary pedigree, powerful performances, and technical wizardry all combine to make for a lasting legacy. And none of us, not even Kirk Douglas, are immune to getting "A Whale of a Tale" stuck in our heads.

But even though 20,000 Leagues is a family film with a fun adventure plot, grown-ups might spot a lot of stuff that would go above a kid's head. From ironies and real-life implications to historical bonuses and technical sophistication, here are things only adults notice in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea briefly becomes a Western

Disney's 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea ultimately lives up to its title, offering audiences both submarine adventure and breathtaking underwater photography. But before it sets out to sea, it isn't just in a different setting — it's in a different genre.

The scene that introduces Ned Land (Kirk Douglas) is straight out of a Western. Filmed on a borrowed Universal Studios backlot that's all dusty streets and wooden storefronts, the San Francisco sequence stands out like a sore thumb. The scene is full of frontier chaos. And in the middle of all the shouting is Ned Land, sauntering down the street with — in a risqué touch for Disney — a woman on each arm, both of them in the kind of colorful and low-cut dresses that older Westerns often used to signify members of the oldest profession.

When his swagger and skepticism lead him to heckle a man sharing stories of a "monster," he provokes a fight that gets him shoved in the mud. It quickly turns into an all-out comedic mob brawl that's like nothing else in the movie. This mini-Western is the good and bad of Ned in a nutshell, like the Nautilus is the good and bad of Nemo (James Mason). He's lively and clear-headed, but he's also impulsive and often driven by his baser instincts. It sets him up as the film's flawed protagonist and Nemo's true opposite, like they really are from two different worlds — or at least from two different movies.

It's cynical about sensationalized news stories

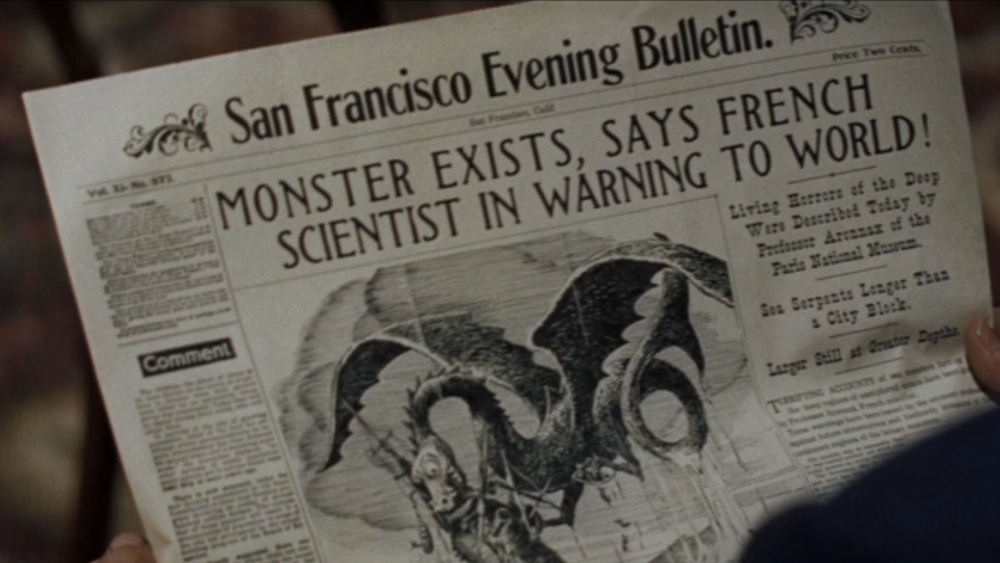

Tabloid-style journalism — as exaggerated and splashy as possible, never mind the facts — has been around forever, and 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea takes aim at sensationalist reporters by inflicting some crazy headlines on poor Professor Aronnax (Paul Lukas).

Scholarly and earnest, Aronnax repeatedly assures the circle of journalists hounding him that he knows nothing about the supposed monster that's attacking ships. The most he will do is engage in a tiny bit of wistful scientific speculation, musing on how the ocean's depths have some surprising creatures in them and conceding that, hypothetically, a big enough sea creature could destroy a ship.

The worldlier Conseil (Peter Lorre) knows immediately what all this could lead to. "Don't you print that," he snaps at one of the reporters. But it's a lost cause ... they've got their headlines.

In a particularly great touch, one of the reporters is already sketching the purported monster. His colleague inspects the drawing and advises him, "Put some wings on it." The next scene shows us — and an aghast Aronnax — a newspaper that features a winged sea serpent whose deadly presence Aronnax has apparently confirmed. Like Conseil, we're not surprised. Science news is especially vulnerable to getting jazzed up if headlines won't wait for all the evidence to be processed and triple-checked. Only adults can summon the right level of weary, rueful recognition for this one.

A picture of Abraham Lincoln is a key thematic touch

In the ward room aboard Captain Farragut's (Ted de Corsia) ship, there's a prominent portrait of Abraham Lincoln. This is a little bit of an Easter egg for fans of Jules Verne's original novel, where the frigate itself was called the Abraham Lincoln. And since the movie is set in 1868, just three years after Lincoln's assassination, it's also a nice historical detail.

But more than that, it's a subtle way of indicating the movie's principles. Most of the film is a battle of ideals and philosophies, with Nemo's cynicism about civilization — and his disregard for the lives of anyone other than his crew — squaring off against Aronnax's allegiance to science and honor, Conseil's loyalty and realism, and Ned Land's practicality and individualism. The latter three are all on the side that civilization is worth keeping and worth engaging with.

The movie is on that side, too. Nemo's hatred of the penal colonies is sympathetic and even admirable, but he lets it poison him. The portrait of Lincoln reminds us that it's possible to fight for ideals — and even wage a war for them — without descending into Nemo's bleak madness. But when Nemo decided that the world above was inherently degraded and corrupt, he fled from it. He missed that there were people up there who would have shared his values. As a result, he ignores the best parts of humanity instead of commemorating them, and that's part of his tragedy.

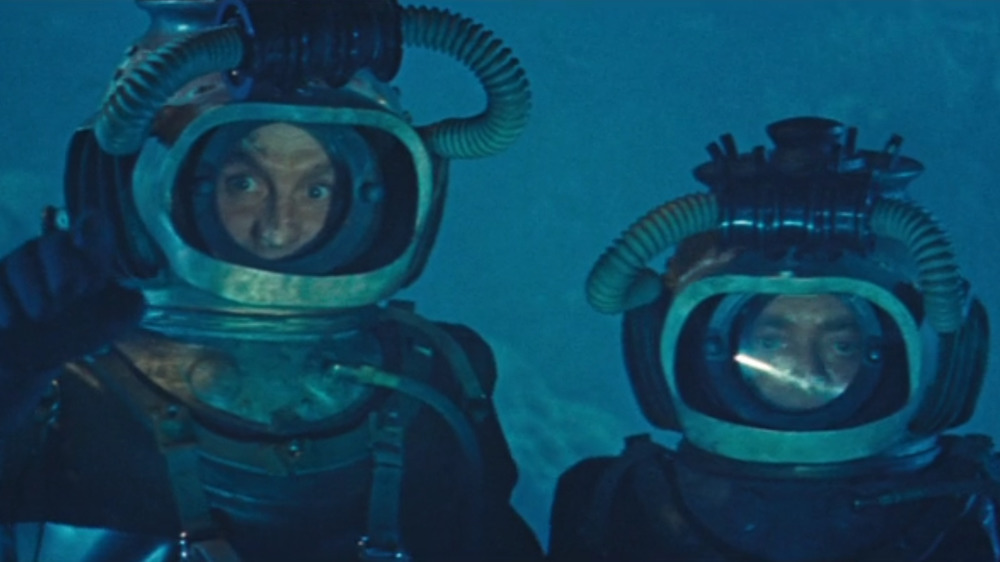

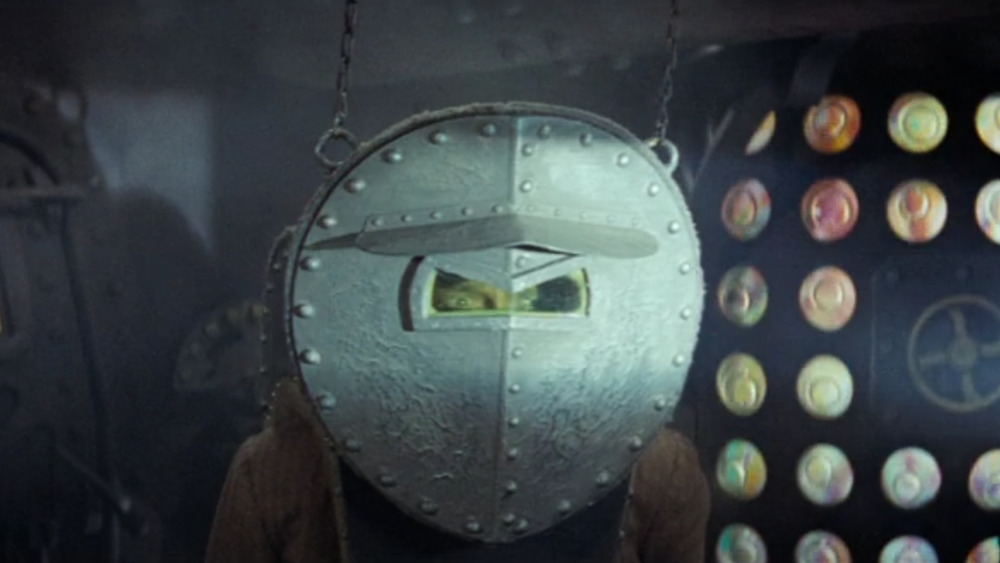

Adults will notice some of the origins of steampunk in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea

Steampunk is a sci-fi subgenre that imagines technological development skyrocketing in the Victorian era, leading to things like steam-powered robots in the 19th century. Part of the genre's appeal is purely aesthetic. Those retro designs just look cool. Seeing familiar technology — or at least familiar bits of speculation, like giant robots — done in an old-fashioned style makes it all feel new.

Discussion of the genre has been around since 1987, but it didn't spring out fully formed. There were obvious predecessors, and 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea is one. The Nautilus is a proto-steampunk delight, evoking our admiration at the marvels the sub can accomplish with technology that's styled like it's from the 1860s. Even something as simple as looking out the window comes with a flourish, as Nemo pulls a brass lever in order to make a protective metal screen dilate open.

It isn't all about the tech, either. Hidden islands, underwater farming, and the lost city of Atlantis are other bits of sci-fi and fantasy wonder that are grounded in a vanished era. We know none of this happened ... but it just looks so good. No wonder it helped spawn an entire subgenre and an aesthetic movement.

Nemo must have a very talented chef to disguise all that seafood

Nemo claims to scorn the outside world to the point that all his food comes from the ocean, and we see the Nautilus crew working an underwater farm and hunting fish and sea turtles, so it checks out ... right up until you think about the dinner scene where Nemo sets a lavish spread for Aronnax, Conseil, and Ned.

It's all seafood, but somehow, it's prepared in such a way that none of the men — including professional sailor Ned Land, who must've eaten his share of fish in his life — can recognize it. How exactly does Nemo's chef disguise "fillet of sea snake" as veal? And, for an even better question, how does blowfish, presumably a white meat, pass for lamb, which is definitely red meat?

And, for the question that finished off Ned's appetite for good, how do you make "pudding" out of "sauté of unborn octopus?" Maybe we don't want to know. Nemo does say the latter is his own recipe, and he is the man who somehow invented a nuclear reactor in the 19th century. Maybe he was on such a roll that he went ahead and developed molecular gastronomy, too, and all the food on the Nautilus has been altered on a chemical level.

Nemo's discovery of nuclear power could have huge ramifications

In Jules Verne's original novel, the Nautilus is powered by electricity. With a nod to updated scientific wonders — and horrors — the 1954 adaptation makes the submarine run on nuclear power, instead. Nemo even allows Professor Aronnax to see the otherworldly glow of the power source, at least once Aronnax takes shelter behind some shielding.

Only adults are really equipped to understand exactly what this change means for Nemo. Inventing a nuclear reactor in the 1860s isn't just the work of a scientific genius, it's the work of a scientific genius almost a full century ahead of his time. This adds pathos to Nemo's decision to bury his scientific knowledge with his death, knowing that humanity isn't yet ready to deal with what he's brought into the world.

The implications of his discovery are enormous, and they would've been fresh in the audience's minds in 1954. While the film focuses on the sheer wonder of the Nautilus as a scientific achievement, adults are probably going to immediately think about nuclear bombs. It lends an additional sense of danger to the movie if you think about how much destruction could really result from Nemo losing all control. When the Nautilus goes down at the end of the film, we all breathe a sigh of relief.

Those giant squid effects might remind you of something

The giant squid in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea is a famous creature effect, and its attack on the Nautilus is one of the biggest and most memorable scenes in the film.

The giant squid has an almost uncanny resemblance to its aquatic monster successor, the shark in Jaws. It's not just that both manage to make mechanized rubber terrifying or that they both leave a huge impact with relatively little actual screen time. It's that they were both designed by the same man, Robert A. Mattey, who designed the iconic but infamously malfunctioning "Bruce," the mechanical shark. While Bruce's unreliability helped lead to Jaws keeping its monster off-screen, heightening the suspense, 20,000 Leagues shows us how striking Mattey's effects could be under the right conditions. After all, a big problem with Bruce was that the saltwater kept eating away at him — not a problem with the squid attack, which was filmed in a freshwater tank on a Disney soundstage.

Both monsters get the benefit of a particular shot that uses Mattey's work to the utmost. The squid's body largely remains stationary, with its tentacles whipping around by wires and air hoses, but the real horror is its beak, which snaps open and shut hungrily as a hapless victim slides towards it. It's a horror tactic that shows up again in Jaws in the attack on Quint (Robert Shaw), and the similarity in the effects is unmistakable.

Sailors do like their grog

For a family movie, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea features a surprising amount of alcohol consumption. Some of it will probably slip under a child's radar, as when Ned razzes a speaker by saying he can smell his breath. "Boiled down for his oil, lads, there'd be free grog for all hands."

But a lot of it is right there on the screen. After he saves Captain Nemo's life — a principled act of heroism that he can't really explain — Ned announces that he'll deal with the decision by getting drunk, since "there's only one thing a fella can do when he's made a mistake as big as this." He even resorts to the very bad idea of drinking the extremely high-proof alcohol that's being used to preserve bottled specimens. Sure, in the movie, it's a problem partly because he accidentally gulps down one of the specimens in the process. In real life, it would be the near-equivalent of chugging a bottle of disinfectant, and it's hard to watch Ned do it without wanting to leap through the screen and stop him. No drunken party-of-one is worth that.

The characters in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea have names highlighting their roles

A little bit of language knowledge reveals some hidden significance to characters' names in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea ... and one of them needs no analysis at all.

The grandest symbolism goes to Captain Nemo, whose name, in Latin, translates to "no one." It highlights how alone he is — though he has his crew, none of them really stand out as individuals or close friends — and it also adds to his mystery. For the whole start of the film, the world mistakes his ship for a monster and doesn't even know that he exists. He's no one, and he believes in no one.

Conseil, on the other hand, has a name that ties him to other people. Conseil is French for "advice," and as Aronnax's loyal apprentice, that's what he gives. He's wiser about the world than the sometimes naïve professor, and he represents reason and rationality. When he and Aronnax start disagreeing more often, it's a sign Aronnax's thinking has been compromised by Nemo.

Then there's Ned Land, whose name is as straightforward as he is. Of the three prisoners, he's the most strongly opposed to Nemo, whom he sees as dangerously unstable. Even though Ned is the professional sailor, Nemo is the one who's really in love with the sea and everything it has to offer. It only makes sense for his opposite number to have the name "Land," emphasizing the fundamental differences between them.

Adults will notice that Nemo's approach to civilization is pretty hypocritical

After his horrific experience on a penal colony island, Nemo claims that he's rejected all human civilization. He insists time and time again that he has no use for anything on land and that he wants an underwater life away from human evils and complications.

But despite what he says, Nemo still holds onto civilization. His private rooms are lined with books and art, and it's not like they appear to be printed or painted on seaweed or made exclusively by members of his crew. They probably aren't the results of odd, coincidental salvage runs, either, since he's both a connoisseur and someone trying to keep up with contemporary scholarship. Apparently, human civilization is just fine when it's producing things Nemo himself wants.

He even replicates some of the problems of the world above. Life on a submarine might sometimes demand a chain of command, so maybe it makes sense that Nemo is the captain while the rest of his men are merely crew. But when he takes Aronnax, Conseil, and Ned as guests/prisoners, there's no need to keep any social separations between them. But he does it anyway. Even under the sea, class distinctions prevail. Nemo gives common sailor Ned Land a working man's uniform to wear while his clothes dry, but Aronnax and Conseil get jackets and neckcloths closer to Nemo's own. Ultimately, Nemo's independent world beneath the sea doesn't seem that far away from the society he claims he wants to escape.

At the end of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, the surviving characters' fates are far from certain

Captain Nemo is the only major character who gets an obviously tragic ending, although at least it's on his own terms. He goes down with his ship, destroying the Nautilus and the island of Vulcania to prevent the surrounding warships from misusing his scientific discoveries. Meanwhile, Aronnax, Conseil, and Ned Land have escaped on a skiff. Ned even manages to rescue Esmie, the friendly, dog-like seal. Sure, their happy ending is marred a little by Aronnax losing all his scientific notes, but even he concedes it might be for the best.

But from an adult perspective, their happy ending might not qualify as a happy ending at all. They've escaped the initial blast and the mass suicide of the Nautilus crew, but now they're in the middle of largely uncharted ocean. Vulcania was a secret island, so there probably isn't any land nearby. How far can they possibly row that skiff? And how will they know where to take it?

Getting to dry land might be the least of their worries, though. Nemo discovered nuclear power, and given the mushroom cloud that blooms over Vulcania, it's likely that he destroyed Vulcania with a nuclear bomb. Ned, Aronnax, and Conseil could be looking at a hefty — and probably deadly — dose of radiation poisoning, and they don't even know it.

We could be living in the future Nemo hoped for

Nemo believes that when humanity is ready — "in God's good time" — his scientific discoveries will somehow find their way back into the world, and other people will recreate his work. And since 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea makes nuclear power the cornerstone of Nemo's scientific development, the movie implies a question: "If we have this power now, does that mean that we're ready to use it?"

It was a question that was already meaningful in 1954, and it's stayed meaningful since then. The implications are simultaneously hopeful and foreboding. On the one hand, it suggests that we could be fulfilling Nemo's hopes. The time has come to embrace and celebrate all our scientific opportunities. This would've had particular real-life resonance when the movie first came out, as the actual USS Nautilus had just become the first submarine to run on nuclear power, literally fulfilling Nemo's prophecy.

On the other hand, it's hard to think about nuclear power without also thinking about nuclear weapons and nuclear meltdowns. The discoveries have come around again, but they haven't always been used safely or peaceably. This knowledge helps Nemo's pronouncement stay both hopeful and bittersweet, giving the movie a nicely complex final note.