The One Comic You'll Never See On The Big Screen

Saga is a hard comic to describe. One of the best short explanations is "Game of Thrones meets Romeo and Juliet meets Star Wars," and even then it falls short. It's the story of two lovers, Marko and Alana, from opposite sides of a galactic war. Their home worlds, the technological planet of Landfall and the magic-using moon of Wreath, want them dead as the very existence of their relationship (and worse, their lovechild, Hazel) is a political nightmare for both sides. The story follows their struggle to find a safe place in the galaxy to raise their daughter while being pursued by both of their home worlds, dangerous mercenaries, and Marko's furious ex-fiancée Gwendolyn, as well as vicious aristocratic robots with televisions for heads.

It's a masterpiece in terms of world building, character development, plot, themes, and artwork. It has a large and growing fanbase and a growing list of accolades. But don't hold your breath for seeing it on the big screen: Saga's writer, Brian K. Vaughan, has gone on record as saying he wanted to develop a comic series that could never be adapted to film or television. Illustrator Fiona Staples has suggested he was burned out from working in television, having been a writer on Lost and Under the Dome. Both of these artists have made full use of the medium to tell a story unfettered by the constraints of the screen, making it a nightmare for anyone who might want to adapt it in the future.

The visuals would be too expensive to do justice to

One of the advantages of comics is the freedom to indulge an artist's imagination without worrying about special effects budgets or technological capabilities. The budget for CGI and practical effects on a Saga movie would be simply gargantuan. Thanks to Fiona Staples, the comic looks really good. But to adapt the universe into live action would be extremely expensive. There would also be so many ways it could go wrong and end up looking ridiculous.

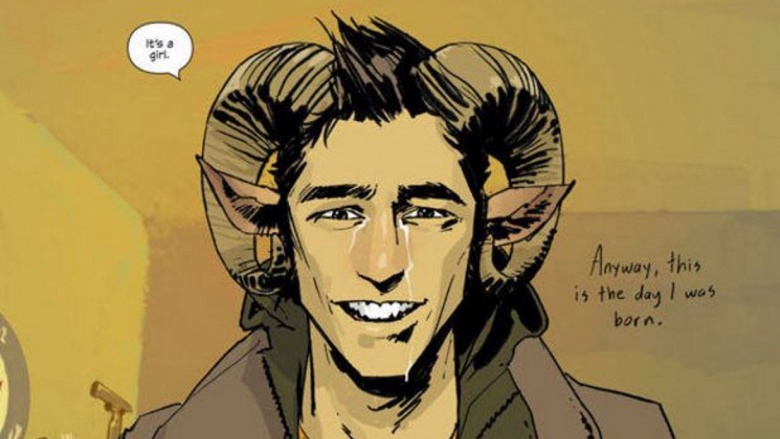

The Saga universe looks unique, combining elements of science fiction with fantasy as well as plenty of perfectly mundane imagery. Staples can bring it all together seamlessly on the page, but translating it into live action would be a challenge. They have taken full advantage of the freedom comics allow to explore character designs, and while Marko with his horns and Alana with her wings might not be difficult, things will become more challenging when expanded to the full range of side characters, from the ghost babysitter to the mermen tabloid reporters and the grasshopper-like teacher.

That's not even getting to the monsters, which are frequently huge and hugely freaky, as well as the variety in the environments. The story takes place on various planets, moons, planetoids, deep space, a comet and in one case a giant egg, as well as various space vehicles including a rocket tree.

Of course, it could all be done. Avatar and Guardians of the Galaxy were just as challenging. But it couldn't be done right now without spending a lot of money—and there's also the danger that much of the soul of the series would be ripped out in the process.

The art is an integral part of the story

In a 2016 interview with Vulture, Vaughan explained, "This is a weird book. There's a lot of bizarre, tough-to-swallow s—, and Fiona makes it so accessible and inviting. So many people have come up and said, 'I saw that first cover for the first issue of the first collection, and said, 'I have to see what's going on.'" You turn to that first page and Fiona just sucks you in."

When preparing new arcs for the series, Vaughan will ask Staples what kind of environments or creatures she'd like to see, and she'll usually give a vague answer like "ruins" or "golems." He'll often work them into the writing process, as well as specific suggestions ("How about we make these characters mermen?") and entire characters, like Ghus the seal guy and his land-walrus Friendo.

Staples' art is just as important to Saga as Vaughan's writing, in terms of character development as well as making seriously loopy ideas accessible and beautiful at the same time. Some have suggested trying to have the best of both worlds by adapting the comic into an animated series which would help to maintain Staples' style while avoiding the costs and potential failures of making a live-action movie with CGI. It's a great idea in theory, but in practice has to confront a very serious obstacle.

The animation ghetto still exists

Animation (and, indeed, comics) have long been considered to be only for kids, with most exceptions to the rule being outright subversive works like Fritz the Cat. In recent decades, the animation ghetto has eroded somewhat, thanks to the mainstream success of The Simpsons and South Park as well as groundbreaking cartoons for adult viewers broadcast by Cartoon Network and Adult Swim.

The problem? They're almost all subversive comedies with tasteless humor. Not that there's anything wrong with that, but today the Western view divides animated works into two broad categories: children's fare and adult humor. There's certainly cross-pollination going on: some children's cartoons are enjoyed by stoners or men who identify strongly with cartoon ponies. Sure, there are more serious cartoons enjoyed by both older kids and adults, such as Avatar: The Last Airbender. But most animation rarely delves into dramatic works aimed solely at adult viewers, a category into which Saga would fit neatly.

In Japan, this isn't a problem, as animated works are more diverse in tone and intended audience. Looking at series like Cowboy Bebop, Samurai Champloo, and Attack on Titan, it's totally conceivable for a Japanese animation studio to produce a worthy Saga adaptation—but it'd be a relatively obscure foreign product facing stiff competition from indigenous comics with local established fanbases. A Saga adaptation would be much more likely to be a project for an American studio, and few would be willing to take the risk due to the adult themes and relative lack of jokes.

And besides, an animated series might be possible. But an animated movie? No way.

Too diverse for Hollywood

Hollywood has a history of "whitewashing"—casting white actors as main characters even when it doesn't make sense in terms of story. From John Wayne playing Genghis Khan to Scarlett Johansson starring in the anime adaptation Ghost in the Shell, there are countless examples of films adding a white protagonist to a plot so the audience "has someone to identify with." While there's sometimes an outcry from certain quarters when an ostensibly white character is played by a non-white actor, the problem of whitewashing and token diversity is a much more pernicious problem in Hollywood movies.

Neither Marko nor Alana are white. Sure, they're aren't exactly human either, but their features are modeled after actual human races. Marko is Asian, designed by Staples on the basis of Japanese actors and models. While he is sometimes mistaken as white by readers, this is only due to the fact Staples avoided using the sort of exaggerated racial features used by many Western artists when depicting Asians. Alana is dark-skinned and intended to be mixed-race; Staples modeled her father as an Indian male. While Hollywood is willing to feature actresses of color, usually alongside a white protagonist, studios have been clearly reluctant to cast an Asian male lead.

Again, they're aliens, and in the Saga universe it's clear that racism is either totally or nearly nonexistent, with the main focus of prejudice on whether people have horns and use magic or have wings and use technology. Still, the themes of prejudice are so crucial to the story. The fact Marko and Alana aren't white may be completely unremarkable within the Saga universe, but it plays an important thematic role in our relation to the work as an audience.

Casting an Asian male lead and a mixed-race female lead wouldn't be impossible for Hollywood, but studios would be... let's say wary. And if the filmmakers got skittish and tried to whitewash the main characters, the negative reaction from the creators and the fans would be intense.

And also too sexy (in the wrong way)

There's more than enough graphic content and adult themes to earn a Saga movie an R rating—and that's not even getting into the violence. Sure, the success of Deadpool has some expecting a new wave of R-rated comic book movies, but there are those who argue this isn't all that likely. Besides, we would argue the explicit content in Saga simply isn't the type studios want to film.

We're not talking titillation and sex appeal, wherein a heroine pouts in a low-cut costume or we get get a butt shot of the hero coming out of the shower. We're talking a human-looking man making love to a spider woman. We're talking realistic depictions of childbirth. We're talking a robot displaying graphic sex on his television head because he's been injured in combat. It's not really gratuitous so much as unflinching and occasionally disturbing.

The problem can be understood through reference to a loopy pseudo-controversy over an Saga promotional poster which showed Alana breastfeeding her daughter. Comics artist Dave Dorman decided this was offensive and railed on Twitter, "It seems that in today's desperate-for-sales comic book market, nothing is sacred. In the midst of world-saving adventures, today's modern heroine breastfeeds her child with zero modesty. Talk about work-life balance!"

But the psychology is the problem. The graphic imagery in Saga isn't really saleable in the traditional way. It's either too insane or entirely too down to earth, and either way would make studio executives and their advertising departments uncomfortable.

It's not connected to an established brand

Some might point to a movie like Guardians of the Galaxy as an example of an expensive and unapologetically high-concept science fantasy that still managed to get produced—and made a huge profit. This is true, but it ignores the fact that Guardians was a part of the established Marvel stable. The more expensive and elaborate films based on comics are almost invariably linked to an already established brand with the sort of mass appeal that Saga lacks.

Image doesn't have enough clout in the world of movies and television to have Saga adapted. Back in the '90s, there were adaptations for The Crow and Spawn, which did pretty well but not spectacularly. The 2000 TV movie Witchblade was well received and led to a television series. More recently, Robert Kirkman's success with The Walking Dead allowed him to push for his demon-possession series Outcast to be made into a series. But it's a lot cheaper to produce a film with vampires or zombies in a modern-day setting than it is to put a whole universe on the screen, particularly one as complex as Saga's. Studio executives generally don't read comics, even acclaimed ones, so it would be a hard sell at best.

It's not a superhero movie

It's not coincidence the most elaborate, most expensive movies these days are superhero films. There's a reason the most expensive comic book movie franchises are for Spider-Man, the X-Men, the Avengers, Iron Man, and Batman. For a non-superhero comic like Saga to get the funding necessary to work would require a budget equaling that of a Marvel franchise movie, and it's hard to imagine a studio willing to fund that.

There are film adaptations of comic series which aren't superhero-centric, of course. Most of the time they end up being relatively low-budget cult films like Scott Pilgrim vs. The World or Kick-Ass. There are the occasional blockbusters based on non-superhero comics, like 300. But they're few and far between. In the current Hollywood climate, there is almost no possibility of seeing a Saga film ever getting the green light.

We might be wrong?

Vaughan has gone on record as saying he doesn't believe there are the technological or financial means to make a Saga movie or series, but he's open to being proven wrong, "especially if Paul Thomas Anderson is looking to adapt a pervy space fantasy for his next project." Neither he nor Staples are particularly keen to see Saga adapted for the screen, in other words, but neither have they entirely rejected the possibility.

After all, stranger things have happened. George R.R. Martin spent over a decade rejecting movie proposals for A Song of Ice and Fire, exercising "the sexiest word in Hollywood: no." But when David Benioff and D.B. Weiss approached the author and proved their sincerity, Game of Thrones was born. Meanwhile, an earlier Vaughan series, Y: The Last Man, appears to be moving forward on the FX network. Vaughan has been joined as co-showrunner by Michael Green, who worked on the upcoming American Gods and Logan and wrote the criminally underrated series Kings.

Comics adaptations are making bank, and the studios are always looking out for new properties to adapt. It's certainly not impossible.

That might not be good either

All this being said, some studio could go and make a Saga film anyway—and mess it up completely. Bad CGI could reduce awesome environments to incoherence, and cool characters designs might end up looking outright goofy. The graphic elements could be carefully pruned out, while adding in scenes of unnecessary T&A. The diversity in the cast could end up limited to characters who are primary colored or otherwise obviously non-human. They could make a dark and gritty re-envisioning, or compose a score based on ironically dated pop music. They could grind the plots and subplots into a single two-hour experience, or intend a franchise but give up after the first film when earnings are too low and reviews too scathing.

There are so many ways it could go wrong, we're loathe to imagine the ways it could go right. It's probably best to just enjoy Saga in the medium for which it was intended. There are plenty of other worthy comics still waiting to be adapted anyway.