The Truth About The BAU That Only Hardcore Criminal Minds Fans Know

Why would a man kill ten people by viciously strangling them? That's the sort of question that drives the crime solving on the CBS procedural Criminal Minds. The series sets itself apart from other case-of-the-week detective shows by taking inspiration from the FBI's Behavioral Analysis Unit — a real department that's gained renown thanks to several pop culture interpretations. The BAU uses criminal profiling to look at why a crime was committed, and in the hopes it will lead them to who actually did it.

Criminal Minds is far from the first on-screen depiction of the BAU, though it is the most prolific. Back in the '80s, writer Thomas Harris took inspiration from FBI agent and early criminal profiler John E. Douglas to write the novels that spawned the classic horror film The Silence of the Lambs, the critically acclaimed Hannibal, and the newest series, Clarice. However, each of those adaptations focuses on the fictional killer Hannibal Lecter and the handful of FBI agents that know him. Criminal Minds approaches the BAU as a team of characters, bringing viewers into its inner workings and cultivating an intimacy with the organization.

Yet even after spending over 13,000 hours with the BAU — for those who've seen all 15 seasons — there are a few things about the real BAU that even the most dedicated Criminal Minds fan might not know.

The BAU started with interviewing convicted serial killers

The roots of the BAU — originally called the Behavioral Science Unit — date back to the '70s. FBI agents John E. Douglas and Robert Ressler set out to understand what makes a serial killer tick in the hopes of finding a pattern that could help future cases.

They interviewed 36 imprisoned murderers and rapists, including the infamous Charles Manson and the Son of Sam, in an attempt to understand what compelled them to ruthlessly hurt people. The interviews consisted of questions such as: What was your childhood like? What's your relationship with your parents? Do you have any traumas to share? To build trust and encourage the conversation, Douglas and Ressler essentially became actors, showing empathy toward the killers where they had none (via Vulture). Netflix's Mindhunter brings this uncomfortable project to life in a somewhat fictionalized adaptation of Douglas' nonfiction book Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit.

There was no scientific methodology to their interviews. The project helped grow the department, spawning the National Center for the Analysis of Violent Crime (NCAVC), which houses the BAU today, but it's now seen as somewhat useless by the BAU itself (via the FBI) because it can't be applied to other cases. Plus, all those details about the history of abuse in a serial killer's past don't mean much to a police department when there is no Penelope Garcia (Kirsten Vangsness) to magically find them on a database that doesn't exist.

Profiling doesn't have a great track record in BAU

In its very first episode, Criminal Minds introduces Jason Gideon (Mandy Patinkin) as he's giving a profile that his real-world inspiration, John E. Douglas, actually formed for a serial murder case in the early '80s. In a daring assumption, Gideon says the killer they're looking for has a speech impediment. In real life, Douglas said as much about California's Trailside Killer and, as it turned out, he did have a stutter.

For a New Yorker piece on profiling, Malcolm Gladwell wrote that criminal profiles often get just as much wrong as they get right when it comes to details like the killer's race or social life. Out of 184 cases in the '90s, he wrote, the British Home Office found the criminal's behavioral profile helped solve only five. Gladwell took a grim look at profiling, citing studies and evidence to argue that profilers give plentiful, vague descriptions that can match any number of suspects.

There's little scientific evidence to support the basics of profiling, partially because there simply haven't been many studies on it (via Psychological Bulletin). Even the BAU acknowledges this in their study Serial Murder: Pathways for Investigations, published in 2014, though they're still gung-ho about profiling. Others doubt whether a victim's body can truly describe the personality of their killer, but luckily for Criminal Minds, TV doesn't have to abide by science.

Retired profiler Douglas won't watch Criminal Minds because of BAU's procedural inaccuracies

Anyone who's seen their profession on TV has undoubtedly found it wildly misrepresented, and Criminal Minds is no exception. It's all about the drama, not the realism. Real life as a BAU agent involves doing a heck of a lot more paperwork than barging into creepy basements guns a-blazing. In an interview with Vulture, retired FBI agent John E. Douglas said he doesn't watch Criminal Minds because "procedurally it's all wrong." To The Philadelphia Inquirer, he commented on series and movies in general, saying, "They have the profilers taking over investigations, knocking down doors, pulling their gun, breaking the rules in an investigation, not Mirandizing [suspects], and it's just over the top and aggravates me."

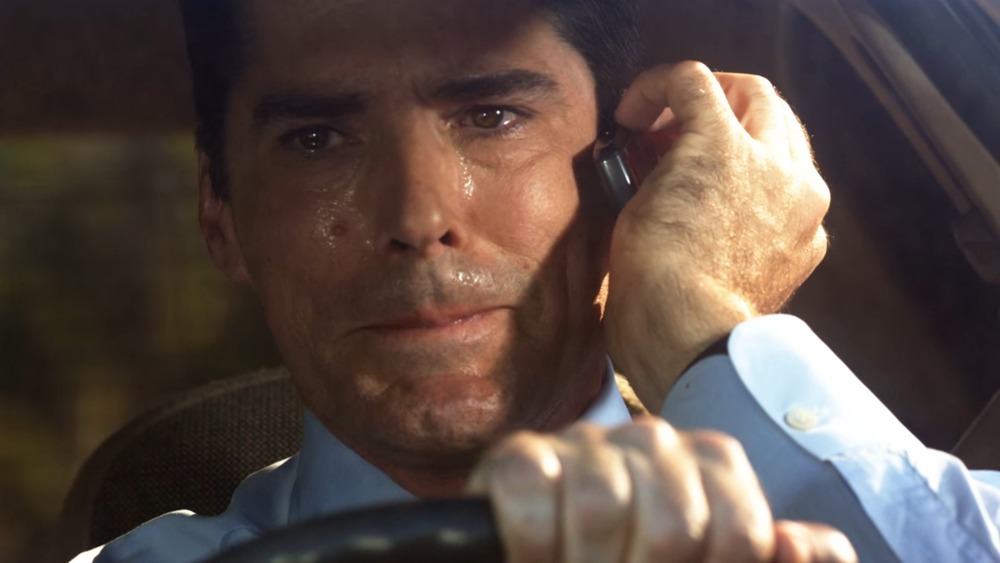

On the podcast Inside the FBI, BAU-2 Unit Chief Mark Hilts refuted another aspect of Criminal Minds: The BAU doesn't take over a case from the local authorities but instead provides assistance, staying a step removed from the investigation. Plus, the job is far less emotional than Criminal Minds makes it seem. Hilts said, "We are not dealing with what the front line detectives have to deal with, so we're kind of removed. And we kind of look at the cases clinically as much as we can and try not to get emotionally involved, which I suppose may sound somewhat cold, but if we get emotionally involved with every single case we work, we frankly wouldn't be very effective."

Actually, the BAU isn't all about serial murderers

Over the course of its long run on CBS, Criminal Minds had to get disturbingly creative to pump out a unique serial killer every week for 15 seasons. BTK's "bind, torture, kill" MO seems fairly straightforward compared to the identical twins taking murder inspiration from praying mantises in the season 9 episodes "The Inspiration" and "The Inspired." Serial killers just aren't as common in real life as they are on Criminal Minds. In fact, serial murders appear to be declining (via Rolling Stone), so the BAU has since expanded to work on other kinds of criminal cases.

There are actually four different BAU units split into different specialities: counterterrorism and counterintelligence; corruption, cyber, and white-collar crime; child victims; and adult victims. Plus, there are even local Behavioral Science Units, such as within the South Carolina Law Enforcement Division.

There is no BAU private jet

"Wheels up in 30," Hotch says, case after case. The team then boards their sweet private jet and flies as far away as California, or as short a distance as somewhere else in Virginia. It provides a nice little set for their personal conversations or emotional struggles, but it sure isn't reflective of the real BAU.

"I think people feel like the FBI does everything in an instant," retired FBI agent Joe Navarro told Business Insider. "Like we have all this aircraft available to us and we can just hop on a plane and go help out Jodie Foster in Silence of the Lambs at a moment's notice. No. We've got to go stand in line at national airports and we've got to buy a ticket and we've got to hope that there's a seat, just like everyone else."

Plus, the real BAU just doesn't travel nearly as much as they do on Criminal Minds. Often, they can do the job from their offices in Quantico. Still, the team on Criminal Minds would never be able to fully theorize about their cases on a crowded public plane — or have their quiet character moments next to dozens of complete strangers. Sometimes, reality just doesn't make for good TV.