Why The Abyss Is James Cameron's Best Movie

You read the headline right: We're naming 1989's The Abyss as James Cameron's very best movie. It's not an easy claim to make. The Abyss? Better than either Terminator 1 or 2? Better than Aliens? Better, even, than Titanic and Avatar, two movies that changed the face of cinema forever?

Sure, The Abyss treads some familiar Cameron footsteps: Militarism at odds with the natural world, blue collar workers versus insidious outside interests, and a basic human drama beneath fantastical trappings. Yet in The Abyss, each of these tropes carries a different demeanor that differentiates the film from the rest of Cameron's work. These details also set the film apart from several other underwater movies that dropped the same year.

The Abyss wears its ambitions on its sleeve. It's a deep-sea feature that was truly shot underwater, not on a smoke-filled soundstage before over-cranked cameras. It shocked the world with its next-level effects. It would, ultimately, underperform at the box office, yet still become a high-water mark (pardon the pun) in Cameron's career. Did it get there because of Cameron or in spite of him? We'll never truly know. But one thing is clear: The Abyss is Cameron's best film, and we're here to tell you why.

The Abyss centers around a domestic drama

At the center of The Abyss is a story about a broken marriage. Deep sea oil rigger Bud (Ed Harris) and his estranged engineer wife Lindsey (Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio) are forced to work together under extraordinary circumstances when a Navy SEAL team requires the transportable oil platform Bud captains. Their aim is to go to the deepest part of the ocean to retrieve lost nuclear missiles. Lindsey comes along, as she developed the vessel and knows it best.

Bud holds intense antipathy for his soon-to-be ex-wife, and, knowingly or not, has poisoned the crew against her. It's seen from the start, as Lindsey embarks with the SEAL team: A topside coordinator, played by Chris Elliott, moans, "Look who's with them ... queen b**** of the universe." The statement is also a bit of an Easter egg for Cameron fans, given Ellen Ripley's epithet against the Xenomorph queen in Aliens.

This conflict might have real-life origins: Producer Gale Anne Hurd was married to James Cameron from 1985 to 1989, with their divorce occurring the same year of the release of The Abyss. Regardless, this subplot avoids easy cliches: Lindsey is more than just an angry wife, and Bud is less than a saintly victim. Both characters arrive as flawed but relatable people, before they are literally plunged into life-or-death drama.

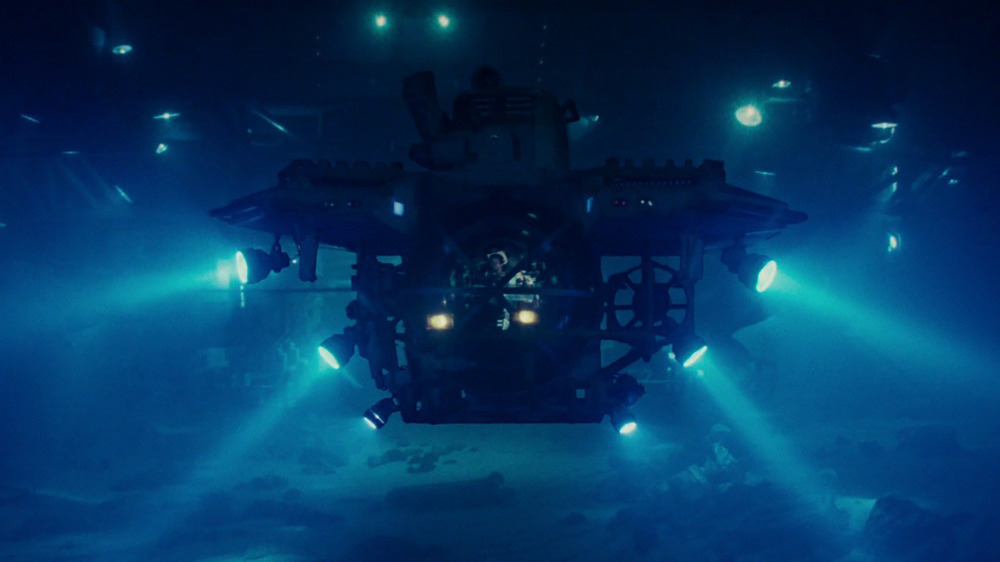

The Abyss' legendary set

Unlike most underwater movies, The Abyss was shot in actual, massive water tanks. Specifically, it was shot in two abandoned nuclear tanks in Gaffney, South Carolina. The light of the sky was blotted out via millions of floating black beads. The actors had to train to become certified divers. All of this required a massive amount of research and development.

As one can intuit, studios aren't very keen on dropping that level of coin. Prior to The Abyss, underwater movies used a soundstage lit to have a blue-green tint. Mild smoke was pumped in to fog the room and develop shafts of light to mimic underwater diffusion and focusing. The cameras would be over-cranked to run faster. When screened at normal speed, movement would seem slower and belabored, as if the actors were pushing against water currents.

Cameron, a devotee of the underwater world, as evidenced not only by Titanic but his many diving documentaries, sought out a degree of veracity not seen on film before. In the documentary Under Pressure: Making The Abyss, audiences learn that such an endeavor was dangerous: This film triumph could have ended tragically on multiple occasions. That risk led to enormous reward, however, which still manages to dazzle viewers many years later.

The Abyss enlivens old Cameron archetypes

James Cameron has a tendency toward specific character types. He favors blue collar people, thrust into extraordinary circumstances involving killer cyborgs, demonic alien creatures, and mindless capitalists. Typically, there will be a team of eight or nine of these people, complete with salty language and tough attitudes, but you'll only really get to know two or three of them. The rest usually end up as cannon fodder.

Somehow, Cameron made these well-worn archetypes work like never before in The Abyss. In large measure, the credit goes to the enclosed space in which our protagonist roughnecks live. Confinement means that you can't shoehorn in too many bodies who won't move the story forward in a meaningful way. Toss in some very good character performances from Todd Graff as Hippy, Leo Burmester as Catfish, Kimberly Scott (in her film debut) as One Night, and you've got movie gold.

Another Cameron archetype is the hard-bitten military man who mistakenly thinks his gun is going to get him out of his unusual situation. The twist this time is that the character of Lt. Coffey, played by Cameron regular Michael Biehn, isn't necessarily evil. He's definitely deep in a paranoid state due to high-pressure nervous syndrome, which drives him to ever-more-manic behavior. But he's not actually a rotten person. This situation makes him a very effective third leg of dramatic tension, as he potentially jeopardizes his mission to retrieve the nukes.

Technology versus the natural world

A common Cameron theme is technology versus nature. But seldom in his filmography is there a stronger case for them to coexist than there is in The Abyss. After all, the Terminator exists to terminate humanity. The space marines haven't a prayer against the Alien Queen and her brood. And the Na'vi? You get the picture. In each of these cases, there's a clear winner and loser.

The Abyss is different, but for many reasons, this was not initially clear to audiences. One thing that was certain is that the underwater creatures in this film are benevolent. They aren't snooping around Deep Core to kill crew members, but to communicate with them and attempt to find common ground. That much can be known from the theatrical cut, but many other aspects of the film were controversially left on the cutting room floor. This lead to extended edits arriving after the fact on home video.

In the extended edition of The Abyss, viewers learn that the "sea angels" are extremely powerful. Outraged by the nuclear missiles, yet moved by Bud's act of single-minded sacrifice, they churn massive stationary tidal waves off the coasts of each continent to send a message to humanity: We can live together peacefully, but if you refuse, we will stop you. It's an old theme made fascinatingly new again.

Ed Harris and Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio are spectacular in the lead

Ed Harris and Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio's performances make The Abyss the triumph it is. At the start of the film, Bud and Lindsey Brigman are an estranged husband and wife thrown into a high-stakes drama. They are not on friendly terms, they're stuck together on an underwater deep sea oil rig, they are in the company of a team of Navy SEALs who play by their own rules, and there's an unknown force down there with them. Oh, and one of those SEALs, tasked with locating lost nuclear weapons, is losing his mind.

In lesser hands, the duo's transition from complete antipathy toward each other back to feelings of love, leading to self-sacrifice for the sake of each other's well-being, could feel forced. Yet these actors keep a measured approach throughout the movie, far beyond mere maintenance of continuity. Viewers truly see their affection for each other renew in a natural, realistic way.

Even more impressive is the fact that not only were Harris and Mastrantonio frequently acting off of visual effects that had yet to be completed, they were doing so against effects that had just been invented. The "pseudopod," a tentacle of water controlled by the "sea angels," represents the digital effects revolution then on the rise. It was up to the two primaries — and the rest of the cast — to make it feel real.

Anger and danger behind the scenes of The Abyss

It could be that the verisimilitude of Harris and Mastrantonio's performances is thanks to Cameron's direction — but perhaps not as one might expect. As detailed in the documentary Under Pressure: Making The Abyss, the director brought both actors to their breaking points, and not in a supportive way.

A key scene in which the drowned Lindsey is brought back to the Deep Core and Bud attempts to revive her was particularly grueling. Mastrantonio left the set justifiably furious, shouting, "We're not animals!" Moreover, Harris almost drowned during an underwater scene, wherein he had to go a long distance without an oxygen tank. The safety protocol was that if he gave a signal, a team would swim in to provide an oxygen regulator. Having held his breath too long, he signaled for someone to bring him oxygen. The crew member brought him a regulator, but it was upside down. Instead of pumping oxygen in and expelling water out, it did the reverse. The mistake was corrected quickly, but the potential of flooding Harris' lungs with water was real.

As Mastrantonio put it, "The Abyss was a lot of things. Fun to make is not one of them."

The Abyss is a milestone for effects filmmaking

Jaws dropped when audiences beheld the pseudopod, a tentacle made of water, controlled by the glowing underwater creatures at the heart of The Abyss. This was a milestone in the digital effects revolution. Primitive CGI showed up in Star Wars in the form of the Death Star plans. Later, Industrial Light and Magic (ILM) presented an extended scene in Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan depicting the power of the Genesis project. (A side note: the ILM team involved with said sequence formed a digital offshoot that would later go independent, thus bringing Pixar to the world.) In both cases, the graphics act as animations and illustrations, not as stand-ins for an object.

Thanks to new, more powerful technology, ILM was able to make the digital pseudopod shimmer and bounce light as a focused volume of water might in open air. The effect brought great acclaim to the production: It won the 1990 Oscar for Best Visual Effects, due to the efforts of John Bruno, Dennis Muren, Hoyt Yeatman, and Dennis Skotak.

Significantly, ILM's digital work fueled Cameron's vision of a "liquid Terminator," sparking the creation of Terminator 2: Judgment Day. By then, the floodgates were open. Taking what they'd accomplished further, ILM's digital department went on to change the face of effects forever in films like Jurassic Park, Jumanji, and The Mummy.

Alan Silvestri's well-scored silences

The Abyss is not a silent film by any measure, but important scenes underwater do not have the benefit of dialogue. Scoring such scenes presents a huge challenge for a film composer –good thing Alan Silvestri was hired to rise to it. Known for big, brassy fanfares (recall the iconic music of Predator and the Back To The Future trilogy), Silvestri deftly handles heightened cinematic moments.

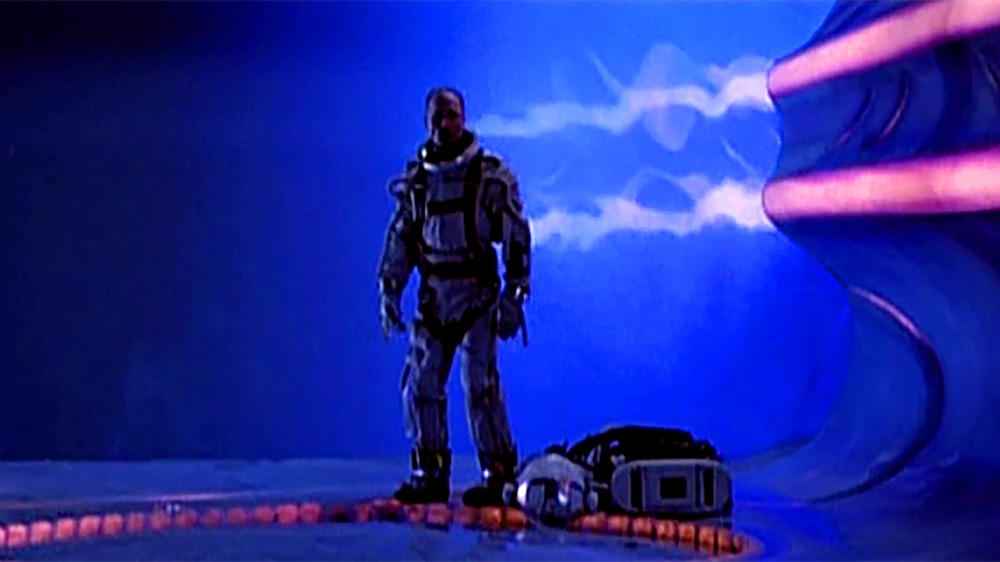

The Abyss demands a thread of tension during long periods of underwater action. In a key scene, the lost nuclear missiles have been located, but the last submersible unit is gone. Bud chooses to disarm them, meaning he will have to plummet solo into the deep-water trench where the missiles have fallen, suffering the effects of heavy pressure in a suit filled with liquified oxygen. He does it mainly to save his crew and his wife, but knows it's "a one-way trip."

Silvestri's music has to balance the suspense of Bud's plunge into the abyss with the intensity of the mission, all the while reinforcing that this is a suicidal act. Aside from intercuts of reactions from the monitoring crew, the music has to do all the talking here. Through a tightly-wound fusillade of strings, an ethereal, angelic choir, and a coda which brings in his trademark bombast, Silvestri delivers.

1989 was drowning in underwater movies

1989 had the bends aplenty with underwater movies like The Abyss, Leviathan, and DeepStar Six. That doesn't even count straight-to-video B-movies also looking to capitalize on the oceanic terror trend. Of these, The Abyss stands tallest. It is hard to know if the producers of Leviathan or DeepStar Six had details of James Cameron's production, but they must have speculated about what his next film would be.

Why is this the case? Because both of those movies have curious similarities to 1986's Aliens, only underwater. DeepStar Six and Leviathan focus on nasty creatures beneath the waves preying upon wholly unprepared humans. Both sets of blue collar crews exhibit a degree of laissez-faire arrogance that proves to be their undoing in 10 Little Indians pick-off fashion. Perhaps more damning, in terms of being judged a pastiche, Leviathan's creature absorbs its victims, leading to a grotesque conglomeration of faces and limbs very similar to the monster of John Carpenter's The Thing.

It's not a stretch to believe that other filmmakers heard that Cameron was doing something underwater, assumed it would be "Underwater Aliens," and proceeded on the basis of the assumption. The Abyss proved to be a more uplifting story than either of its competitors, and the all-around stronger work.

Diversity was not a death wish for The Abyss

Every one of 1989's many underwater movies features a reasonably diverse cast. Why does The Abyss stand above them? For that, we need to recall what the 1980s were like. If a movie of the era features a Black person within a mostly white group, he or she is probably going to die. This trope lives on, unfortunately, but it was particularly strong when The Abyss came out. In the first of 1989's underwater creature features, DeepStar Six, Captain Laidlaw (Taurean Blacque) gets crushed to death under an airlock door in the first half. He doesn't even get a heroic face-off against the beast. In Leviathan, Ernie Hudson's character Justin Jones survives the entire movie, only to be chomped unceremoniously by the return of the sea monster.

This environment is what makes The Abyss' Lisa "One Night" Standing special within this unintentional trilogy. Not only is she a Black woman with agency in the movie, she survives! Imagine that! This doesn't make The Abyss a bastion of cinematic inclusivity, as One Night is the only Black character and "literally just surviving" is a pretty low bar to clear. But she's there for a purpose, and it's not to die in a contrived moment of surprise.