The Untold Truth Of Calvin And Hobbes

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Calvin and Hobbes, that mischievous, spiky-haired blond boy and his anthropomorphic tiger best friend, are essential, authoritative, and indispensable for a huge number of reasons. For one thing, the cartoon pair and their creator went out on top. Often, comic strips overstay their welcome, and over time, the "funnies" in the newspaper just don't live up to their name anymore. Not so for Calvin and Hobbies: The strip stayed golden for years on end, and has only gained more and more of a following as time has gone by.

Fans might long for more adventures starring the indefatigable duo, but when Bill Watterson was finished, he was truly finished. He took a lot of secrets with him, as he's never been one to reveal more than he wants to. The legendary cartoonist constantly (but respectfully) turns down interviews and declines merchandising opportunities: He is quite frank in telling the public that he "enjoys the isolation" of his life. Watterson's fiercely private attitude has given his iconic strip no small amount of mystique — there are a lot of things about Calvin and Hobbes that aren't necessarily common knowledge, even among diehard fans. We're here to uncover those secrets, one monstrous snowman at a time.

Going once, going twice ...

While you can get various collections of Calvin and Hobbes for the typical price of a book, an original strip is a pretty rare thing to see for sale. Ratcheting up their worth is the fact that the approved collections are missing a few of the originally published strips. The Complete Calvin and Hobbes, for example, does not include a strip that jokes about climbing into the washing machine (don't try that at home, kids), and contains a couple of strips that have had their original joke, which hinged on adoption, changed.

So, there's not really any such thing as the "complete" Calvin and Hobbes. Therefore, there is a rarefied air that comes with the territory of owning originals. But an actual, original piece of Calvin artwork from Watterson is so uncommon that people are willing to pay obscene prices for it. At one point, a Calvin and Hobbes original held the record for most money paid for an original comic strip at an auction, at $203,000 ... beating the previous record, held by a Peanuts original, at almost $90,000.

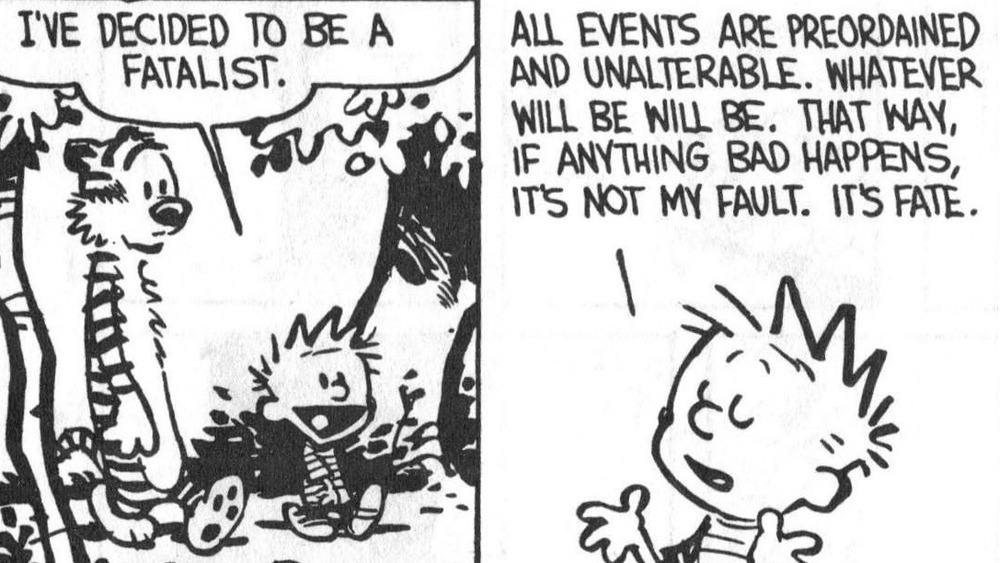

Calvin and Hobbes, theologian and philosopher

If you think that Calvin and Hobbes seem a little bit too intellectual for their age, you might be onto something. The pair are named after a theologian and a philosopher, respectively, whose ideas are centuries old. John Calvin believed in predestination, while Thomas Hobbes once observed that life is "nasty, brutish, and short." In fact, journalist Horace White once asserted that the Constitution of the United States is "based upon the philosophy of Hobbes and the religion of Calvin. It assumes that the natural state of mankind is a state of war, and that the carnal mind is at enmity with God."

So, what does this mean for a six-year-old and his stuffed tiger? "It's an inside joke for poli-sci majors," said Watterson in 1987, who graduated from Kenyon College with a political science degree. Peering at the characters through this lens is worth anyone's time, however, regardless of degree. Thomas Hobbes had a dim view of humanity, which we can see on display in his feline counterpart when he plays devil's advocate with Calvin, or comments on the failings of human nature and how proud he is to be a tiger instead. But where the real Hobbes would call life poor and solitary, in addition to his other choice adjectives, Hobbes proves the opposite, providing companionship and excitement to his best friend.

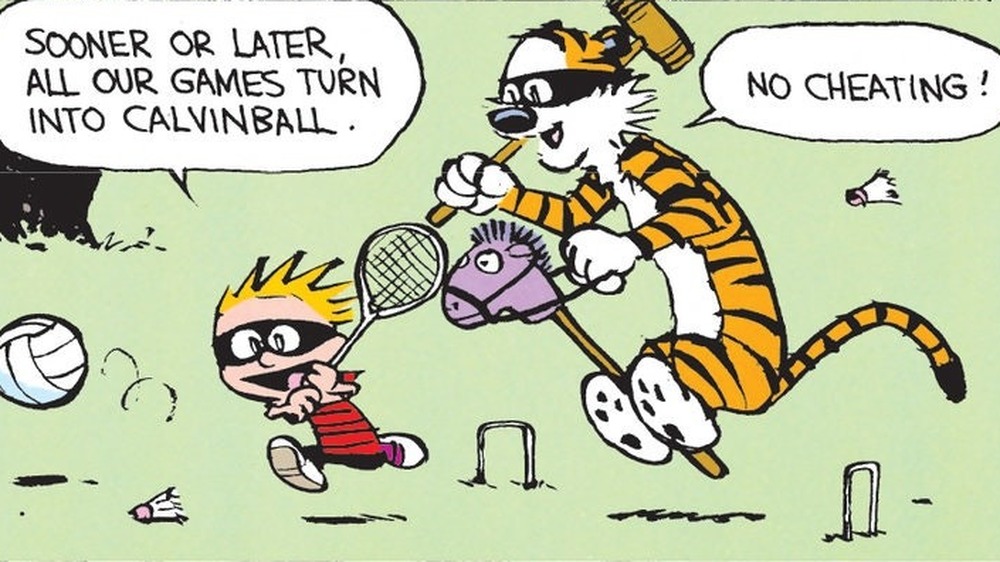

Calvinball goes to college

Fictional sports often find their way into the real world. Fans of Harry Potter, for example, discover the canon in their youth, then end up at college, where, surrounded by like-minded friends, they make the sporty element of their fandom into reality. Thus, students on many college campuses have also formed their own Quidditch leagues, bringing the wizarding world's sport of flying broomsticks into the real world via dozens of teams across the country.

So it goes with Calvin and Hobbes' Calvinball. In Watterson's original conception of Calvinball, the only permanent rule is that you can't play it the same way twice. Calvin further remarks that sooner or later, all of his and Hobbes' games turn into Calvinball. It makes sense that such contagious fun would take hold in the real world: There was once a real Calvinball league at Washington University in St. Louis that intentionally "[strove] for a certain level of confusion" in gameplay. This truly honors the original inspiration: A game that begins as Calvin's revolt against playing baseball.

Spaced out with Spaceman Spiff

Calvin made his debut not in Calvin and Hobbes, but as a side character in an earlier, less successful Watterson comic, The Doghouse. In it, he takes on the role of the bothersome younger brother. As one Redditor pointed out in response to an unearthed Doghouse strip, Hobbes eventually took over that role. But that's not the only connection between the two strips. The new and improved Calvin, king of his own comic (when Hobbes isn't giving him too much trouble, anyway), ended up using the joke from that Doghouse strip in a one of his own.

Not only is Calvin himself based on an earlier prototype, but one of his "alter ego" characters, Spaceman Spiff, also had an earlier iteration. Spiff began as the star of Spaceman Spiff, a spoof of the space fantasy genre, a la Star Wars. The comic "was so bad," Watterson admitted, that he used Spiff in Calvin and Hobbes to poke a little necessary fun at it. Watterson wanted to be an astronaut or a cartoonist as a child, though the astronaut idea was eliminated early on when he "stopped understanding math and science."

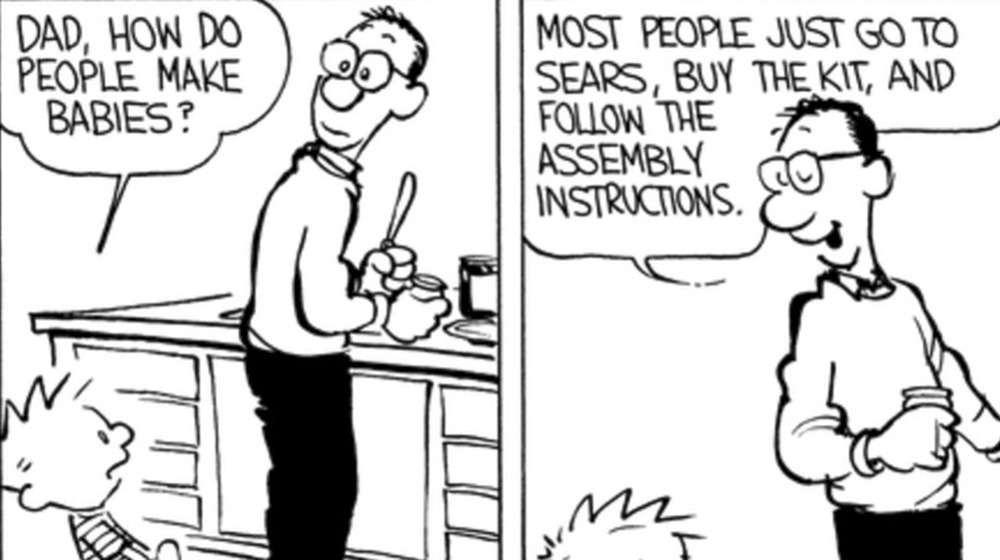

What's in a name?

As the ever-vigilant Reddit community has pointed out, Hobbes almost never refers to Calvin by name. You could interpret this a lot of different ways. It could simply be evidence of how intimate the pair are: Names are superfluous and conversations can simply begin mid-sentence between them. Or you could call into question the nature of imagination, as the strip so often does with cavalier innocence. If Hobbes is completely imaginary and simply an invention of Calvin's own mind, then his perspective on Calvin is probably more congruent with Calvin's own than with an outside observer. We think of ourselves in the first person, of course. So if Calvin wouldn't call himself by name, why should Hobbes, if Hobbes is just another part of his own mind?

Speaking of the significance of names and salutations, Calvin's parents are never named at all. They are certainly important characters in the strip, acting as foils to Calvin and his worldview. As their significance is derived from their relationship to Calvin, it makes sense that we aren't given their names. Little kids don't typically think of or call their parents by their first names. Thus, the fact that we don't know Calvin's parents' names further serves the idea of the narrative as completely beholden to Calvin's own subjective point of view.

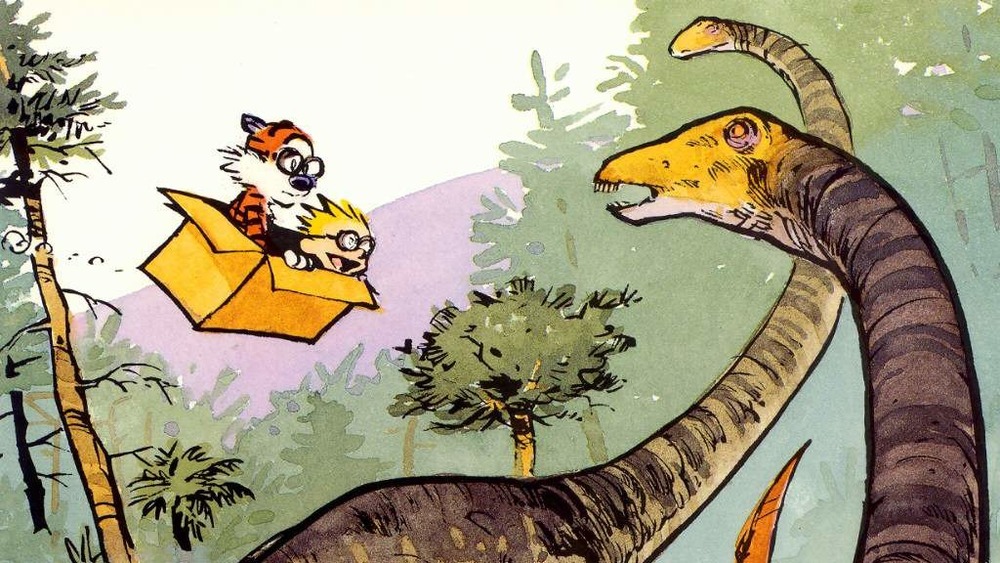

Imagine-era friends

Calvin and Hobbes' depictions of dinosaurs as imagined by Calvin have been praised by actual scientists for their accuracy. When you think of this in terms of the internal congruency of Calvin's perspective, this becomes all the more remarkable. These depictions blur lines between Calvin's imagination and the outside world. They suggest that Calvin has done what kids often do, and developed a fixation on his latest topic of interest: in this case, awesome prehistoric beasts. He's set about drinking up every ounce of content he can get his hands on in libraries and on television. Maybe, through this obsession, he has developed a pretty accurate view of the Mesozoic era — or more simply, perhaps Watterson's accuracy is just a way of portraying the richness of Calvin's imagination. The level of detail present in these panels immerses the audience in a six-year-old's brain.

Calvin's imagination is, however, impacted by the real world. After Jurassic Park debuted and gave the world a whopping case of dinosaur fever, Watterson kept dinosaurs out of Calvin and Hobbes for half a year. Best not to compete with a blockbuster.

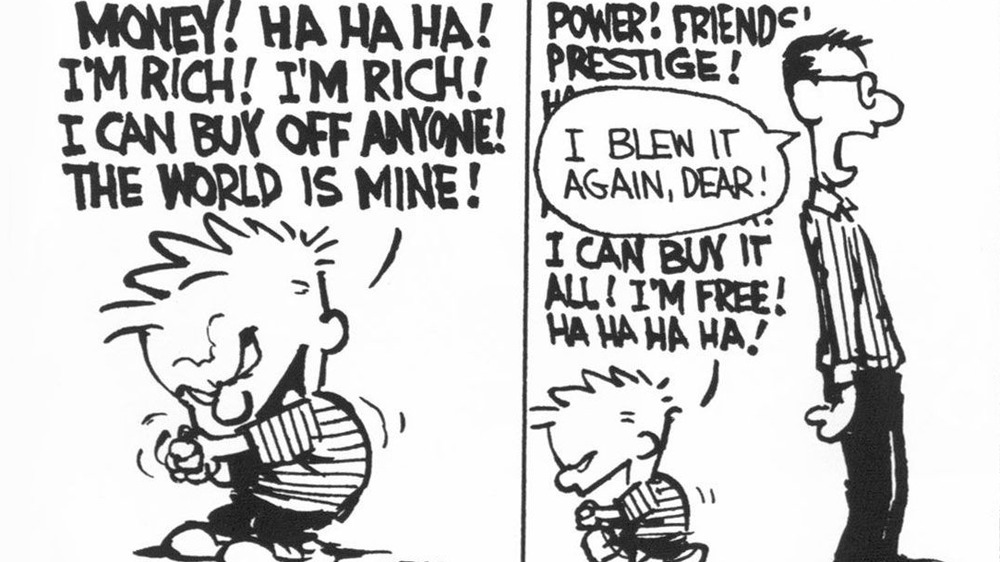

Watterson's license to kill

Bet that title caught your attention, eh? Let us clarify: Whenever there's been hope of a potential Calvin and Hobbes licensing agreement, it's been struck dead by Watterson's staunch opposition. In 1987, The Los Angeles Times reported that Watterson had withdrawn from discussions of Calvin and Hobbes greeting cards and that talks about a television series would not be moving forward. Watterson believed that there was no incentive, on the marketing side of things, toward "understanding what makes the strip work." Products like greeting cards would basically attempt to take upon themselves a storytelling, laugh-getting, character-developing task that Watterson believed should be reserved for the strip. Calvin, he commented, would ironically be more enterprising: "He's pretty much the capitalist."

This opposition to merchandising means that the few Watterson-approved items to have been made add up to an interestingly motley collection. It is comprised of two calendars, a postage stamp issued by the USPS in 2010, a language tutorial book, and a t-shirt from the Museum of Modern Art. No, none of those decals depicting Calvin peeing on something are legit.

Calvin and Hobbes won't be coming to a theater near you

There are no TV or movie adaptations of Calvin and Hobbes. Big names have tried to make one happen, including Steven Spielberg — multiple times, in fact. Watterson wasn't interested. Even more so than a greeting card or a sweatshirt, a film or television series would certainly have to "[try] to do the job" of the strip. In making its own jokes and creating its own narrative for characters purposely designed for the strip, any screen adaptation of Calvin and Hobbes would run a risk Watterson simply isn't willing to take.

But what about Pixar? Doesn't the philosophical pair of a feisty young kid and his stuffed tiger invoke the kind of wonder you expect from a Pixar project? As far as Pixar's animation capabilities go, Watterson has said he's "[blown] away," but he still has no interest in animating Calvin and Hobbes. His reasoning? There's simply "no upside." The characters and their world work exactly as he intends and desires in the strip, so there would be no benefit to putting them in a different medium.

In the end, Watterson has surmised, different forms of media are, well, different. In adapting across medium, it's the medium that gets served, not the material. Calvin and Hobbes is already a perfect union of medium and message, so why change it?

Calvin and Hobbes watch their language

Watterson has made a small number of exceptions to his merchandising rule. Two calendars came out right in the middle of the strip's run, in 1989 and 1990. One was listed on eBay in 2015 for the low price of $275, which, considering the hundreds of thousands of dollars paid for Watterson's original work, doesn't seem so bad. The shirt he licensed for a MoMA exhibit on comics has also continued to ignite fans' desires long after it hit shelves.

Another of Watterson's limited licensing agreements involved a book intended to help children learn language skills. The book, Teaching with Calvin and Hobbes, isn't really a new work, but rather a repurposing of a few dozen Calvin and Hobbes comic strips, organized into units. Each unit begins with a series of strips followed by comprehension questions. There were only a few thousand copies of this textbook made, and, like the other pieces of Calvin merchandise, they are worth a good deal. Prices don't dip below $1,000 on Amazon or eBay for this particular item — one is even listed for $4,999.

Supporting characters

Miss Wormwood, Calvin's long-suffering teacher, is named after an apprentice devil from C. S. Lewis' The Screwtape Letters. She's no apprentice herself, though — Miss Wormwood is world-weary and sour from many years of teaching. One can still interpret her nature as relating to her name, however: The plant known as common wormwood is intensely bitter. It is often used for digestive issues, which can also be seen as relating to the character — Miss Wormwood takes a fair amount of medication.

Wormwood is also an ingredient in absinthe, a high-proof alcoholic beverage with a mystical reputation for altering reality. But Miss Wormwood doesn't alter reality. Instead, she counters Calvin's frequent departures from the mundane and the practical. Though absinthe is sometimes also known as the "Green Fairy," Calvin and his alter egos certainly don't see Miss Wormwood that way: To Spaceman Spiff, she's an alien monster, and to Stupendous Man, she's his arch-nemesis, the Crab Teacher.

As far as other supporting characters go, Susie Derkins, Calvin's antagonist and crush, is named after Bill Watterson's wife's dog, Derkins. She is the only main character with a first and last name. Watterson describes her as the kind of girl he would have liked in high school and that he eventually married.

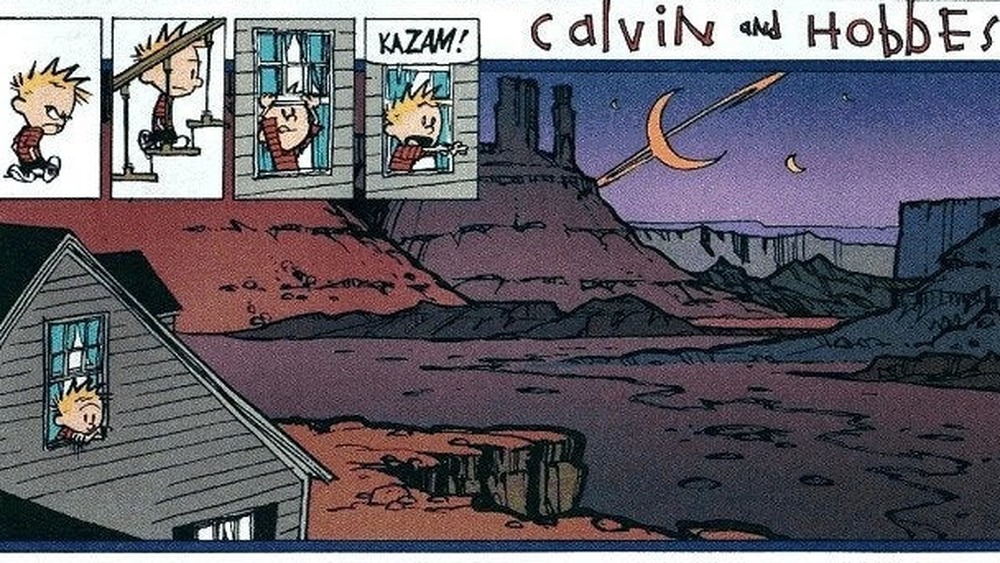

Imagination and reality

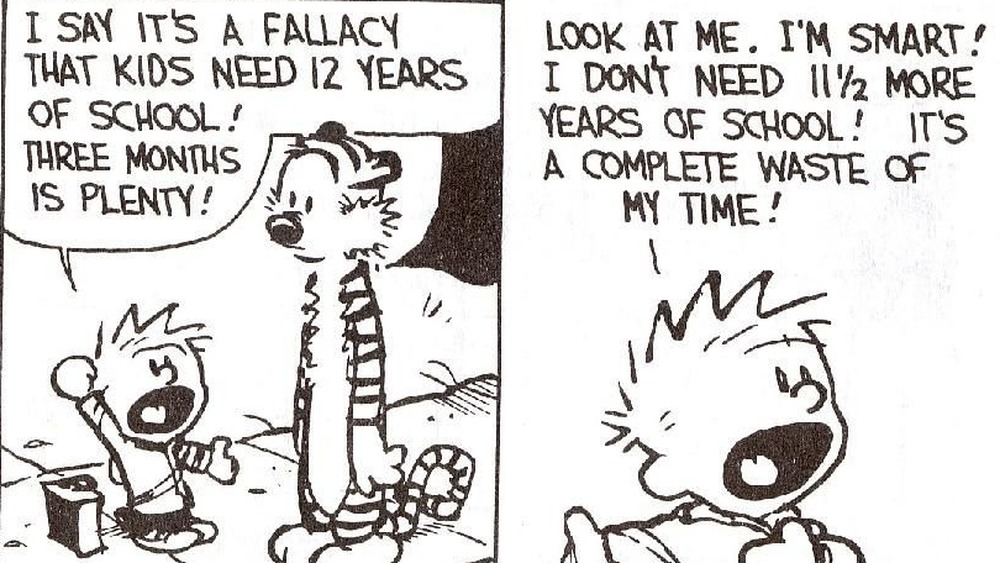

Watterson intentionally drew the products of Calvin's imagination in a more realistic fashion than he did the "real world." Subverting visual expectations gives us a unique window into Calvin's head. This is one of the things that's so genius about Calvin and Hobbes: It uses its medium in striking ways, conveying punchlines and meaning entirely without words. It certainly worked — when the strip began, it ran in roughly 35 newspapers, while at its height, it appeared in over 2,400.

Surprisingly, Watterson commented that the writing is what pushed his drawings into greater complexity. The reclusive and philosophical artist builds complex illustrations on a simple foundation, describing the simplicity of "cartoon shorthand" as what inspired him in Peanuts comics. In comics, a couple of dots and lines can convey unease and allow the audience an instant glimpse into the mind of the character. This brevity appeals to adults, as their lives move so much more quickly than kids'. Calvin's lavishly illustrated imagination, then, defines him as a child. One of the things Watterson loved most about his strip was its disregard for including adult perspectives. It makes sense that this space would hold less appeal for Calvin than the vividness of his spontaneous, imagined life.

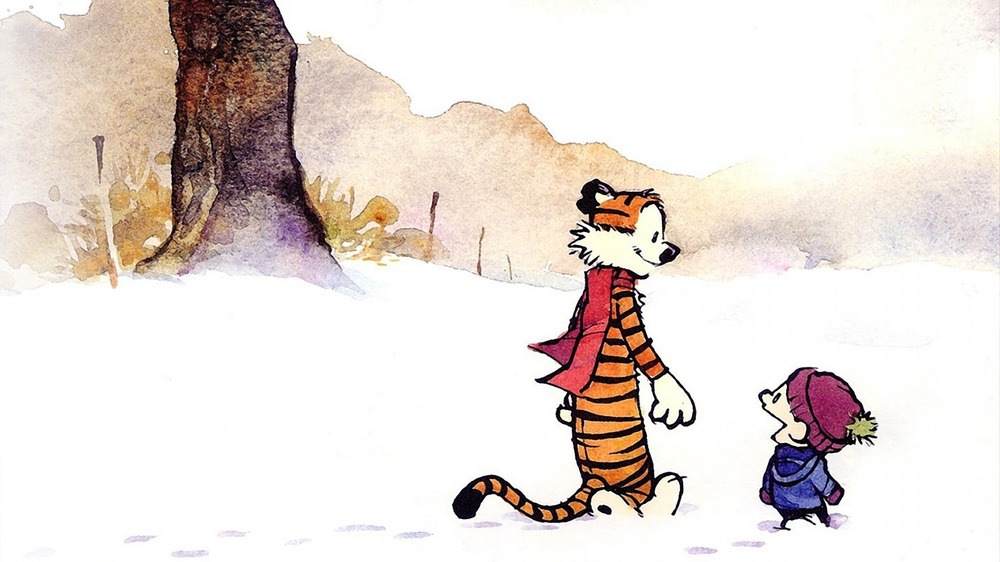

Not exactly imaginary, not exactly a friend

Speaking of reality and imagination, Hobbes is something more than imaginary, to hear Watterson describe it. He's not "a doll that miraculously comes to life when Calvin's around," yet neither is he a figment of Calvin's imagination. Calvin simply "sees Hobbes one way, and everyone else sees Hobbes another way." It's no different from how someone can be a friend to one person, but an enemy to another.

Everyone sees a different view of reality from everyone else. Hobbes simply inhabits two perspectives at once, right in front of us. Each makes as much sense as the other, the way Watterson draws it. He's an embodiment of the "subjective nature of reality," one of the most complex truths of human life. This is a heartwarming and fascinating revelation for fans who miss the character. Conceiving as Hobbes as a more independent being also makes sense: if you were going to create an imaginary friend for yourself, wouldn't you create one who agrees with you, rather than one who constantly bickers with you?