Slaxx Review: The Call Is Coming From Inside The Murder Pants

It's obviously not easy to make a watchable movie about a pair of designer jeans that kills people, but that doesn't mean it's impossible. Slaxx, the new, niche horror/comedy from Canadian filmmaker Elza Kephart, succeeds in pulling off this insane task by keeping things light on runtime, nimble in its storytelling, and heightened in its depiction of reality.

The result is a ridiculous premise crafted into an incisive little statement piece about the ills of capitalism and the exploitative toxicity of corporate retail culture. Just, you know, with people getting choked and exsanguinated by a sentient pair of jeans.

Slaxx, co-written by director Kephart and producer Patricia Gomez, is able to wring so much from its absurd setup partly due to the film's brisk length. At a lean 73 minutes, the movie has exactly enough time to establish a setting, a viable threat, some stylish kills, and a healthy amount of socioeconomic commentary without sticking around long enough for the viewer to begin to process that they are, in fact, watching a movie about a pair of jeans committing murder.

Obviously, the entire affair is a bit much. Despite how well executed the final product is, it does push the envelope right up to the razor's edge of credulity. But given the subject matter's inherent silliness, it's a testament to the storytellers' talent and drive that Slaxx is not, as it easily could have been, a bad joke taken too far.

The sisterhood of the murderous pants

Slaxx is principally concerned with two tethered entities: the trendy fast fashion brand Canadian Cotton Clothiers (CCC, for short) and one of its busiest location's newest hires, Libby (Romane Denis).

The viewer is introduced to the brand and its ensuing lifestyle cult through Libby, a naive believer whose general disposition at starting her first day for the store the night before a hectic new season launch could best be described as "stoked." Like many of its employees and customers, CCC represents more than a job or a product to Libby, but a calling, a commodity easily meant to replace a personality or a life.

Though CCC is meant, quite clearly, to evoke brands like Zara or H&M, the company is shaped with a healthy application of Apple's reality distortion field culture as well. When Libby and her colleagues stand at attention for an in-person pep rally from brand CEO Harold Lansgrove (Stephen Bogaert), it's impossible not to whiff the Steve Jobs TEDTalk energy wafting off his presence.

So when one of Libby's co-workers is seen stealing a pair of jeans from the new season launch, a product the store's sycophantic manager Craig (Brett Donahue) forbids staff from even looking at, the "new iPhone" aura of this particular piece of denim shines through. This article of clothing represents a breakthrough for the supposedly ethical boutique brand, a pair of jeans engineered to adapt to the shape and size of the customer wearing it.

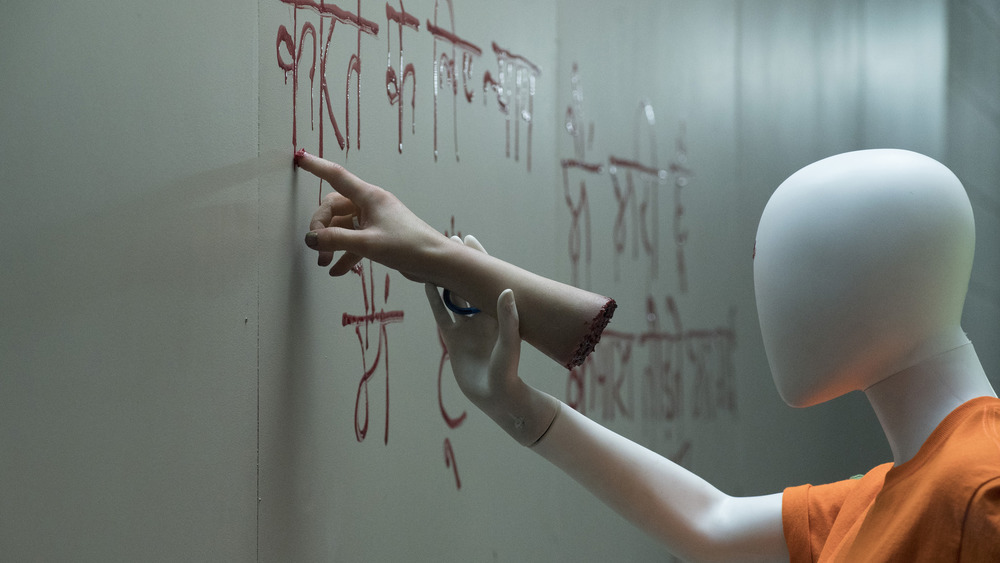

If it sounds like whatever R&D chicanery necessary to design something like this would be just as likely to turn said product into a living death machine, well, that's precisely what happens. The executioner jeans tear through the CCC staff, one illicit dressing room sneak at a time.

There's only but so many ways to film some jeans taking lives, but Kephart puts a great deal of care and consideration into each kill, ranging from a the first victim being squeezed to death by the denim's vice-like python grip to another casualty tripping on her own legs until her head is impaled on a nearby coat rack, proving a woman doesn't necessarily have to jump to feel Beyoncé's pain.

The verve in the kills matches the attention to detail elsewhere, like the hand-stitched font of the film's opening titles, or the CCC logo on the killer pants that fills with blood after each sacrifice. There's also a gut-busting sequence when Craig and another employee argue via their walkie headsets before the camera breaks from the split screen to reveal they've been standing a socially distanced six feet apart the entire exchange.

Like the marketing language of the insidious brand at the film's heart, Slaxx is a film that weaponizes the iconography of branding to produce a sharp and efficient thriller, one whose shrewd aesthetic sense feels like an extra twist of the knife relative to its thematic hangups.

Climbing the corporate ladder to hell

While its obvious stylistic counterparts would be Quentin Dupieux's Rubber or the more recent Bad Hair from writer/director Justin Simien, Slaxx has more in common ideologically with Boots Riley's Sorry to Bother You, another absurdist exploration of capitalism and wage slavery.

As this horror story unfolds, it transforms from a straight up slasher with satirical elements into a haunted house story. The mysterious origin behind the jeans isn't connected to any occult experimentation on CCC's behalf, but rather the blood-soaked cogs within the hungry corporate beast's perpetually grinding gears. For these companies to keep making year over year profit increases, its various workers become lambs to the slaughter, their exploited labor all the oil the machine needs to stay greased.

The tragedy at Slaxx's core is made literal when the jeans' motivation is revealed (a depressing narrative turn best revealed by the film itself and not spoiled by this reviewer), but the real horrifying figure isn't los pantalones de la muerte. It's the cannibalistic impulse retail culture fosters within its employees.

The more comedic elements of the film exist in the way this world's inhabitants are exaggerated. Sections of the CCC storefront are called "ecosystems." The lifer employees speak with the same gleeful irrationality the warmongers in Dr. Strangelove so comfortably spew. It all feels so cartoonish and scenery-chewing, but while the general tenor is heightened, it speaks to a truth at the center of how these businesses function.

It's no mistake that as the bodies pile up and the store is left with a small triangle of survivors, each potential victim represents the primary three levels of retail employee psychology. On one extreme, there's Shruti (Sehar Bhojani), a clothes-folding veteran possessed only of apathy and derision for her current vocation. Then, on the opposite end of the spectrum, there's Craig, who his staff call the "Robot King," a man so devoted to the brand and the nebulous promise of upward mobility he becomes a more villainous presence than a literal textile golem powered by the victims of capitalism.

In between, there's just Libby, a believer whose harrowing experience trying to not get choked to death by some jeans causes her to see the truth behind her new employer's convincing lies. Any viewer who has ever worked a dead-end job like this will relate to Libby's binary choice between sticking around and becoming Shruti or sticking around too long and becoming Craig.

So when she comes to her senses and tries to save the world from the fate that befell her colleagues, the realization that everyone else outside the storefront's locked doors is still under the same toxic and self-destructive spell has that much more impact. The film's caustic and brutal conclusion leaves the viewer with lingering thoughts, with questions about complicity, ethical consumption, and what it would truly take to finally kick the opiate known as consumerism.

Not bad for a movie about a pair of killer jeans.