How Accurate Is Bohemian Rhapsody?

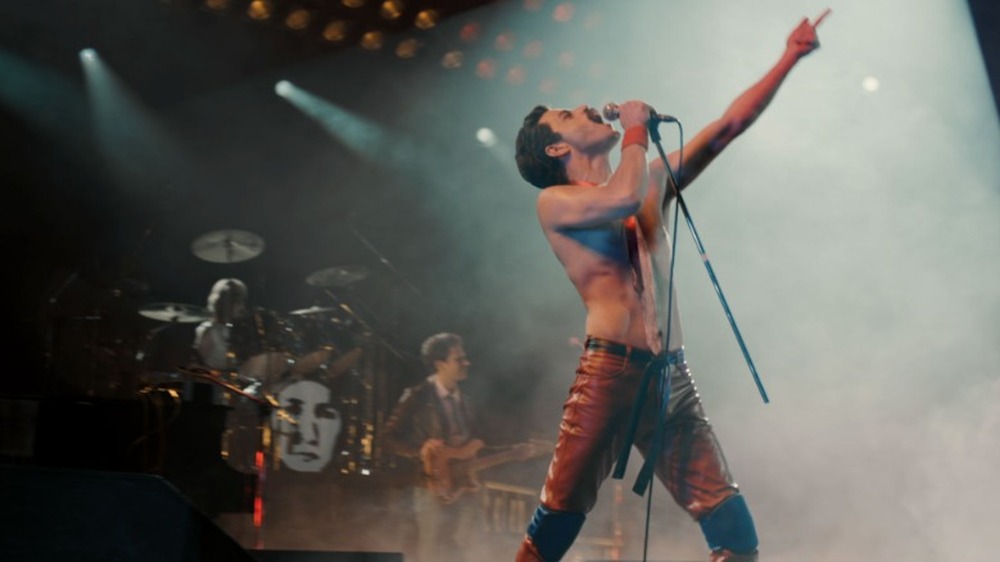

When Bohemian Rhapsody came out in 2018, it had Queen fans all over the world singing, clapping, and stomping along to the band's incredible songbook. For many, it scarcely mattered what movie those triumphant musical sequences were attached to — the plot of Bohemian Rhapsody functioned mainly as a way to get from one meticulously recreated Queen performance to the next.

Still, there was a plot. And a lot of it, too – Bohemian Rhapsody comprises a period of 15 years in total, from the genesis of Queen as we know it to the legendary Live Aid concert at the twilight of Freddie Mercury's career. Splitting its focus between Mercury's turbulent personal life and the ins and outs of the rock music industry, the movie has so much historical ground to cover that some measure of artistic license to fit everything into a cohesive narrative would be a given.

But just how much artistic license was there, exactly? With drummer Roger Taylor and guitarist Brian May on hand as consultants, we can imagine that the movie is authentic about the nitty-gritty of their famously weird writing and recording sessions, at least. But when you look at the broader picture, the timestamps, and the depiction of Mercury's life, things get a little more complicated.

The film liberally rejiggers Queen's historical timeline

For a music history nerd, watching Bohemian Rhapsody might be something of an endurance test. Details and cause-effect relations pertaining to Queen's formation and evolution, as well as the how/why/when of the writing of some songs, are way off in the movie.

For starters, the sequence in which Freddie Mercury meets Mary Austin, watches Roger Taylor and Brian May's band Smile for the first time, then introduces himself and joins the band — all in one night — is pretty much a work of fiction. In reality, Mercury had known Smile's original lead singer, Tim Staffell, for years, and constantly pestered them about joining even before Staffell left, per Ultimate Classic Rock. He also didn't meet Austin until some time afterward.

Then there's the question of dates. Among the movie's many inaccuracies in that department, we have the fact that "Seven Seas of Rhye" wasn't written for their debut, but for Queen II. "Fat Bottomed Girls" couldn't have been played during their first U.S. tour in 1974 because it came out four years later, as explained by DVHN. and "We Will Rock You" wasn't exactly a Hail Mary effort to get the group back in sync in the '80s, as it was released in 1977. Plus, the Rock in Rio concert, which serves as the screenplay's "peak before the fall" moment, actually happened at the end of the movie's timeline in 1985 — that was a few months before Live Aid.

Bohemian Rhapsody also isn't very accurate about who comes into the band's lives and when. Though John Reid really did become their manager in 1975, he left in 1978 under amicable circumstances; he was not fired impulsively by Mercury in the early 1980s. Additionally, Mercury didn't meet his personal assistant Paul Prenter via Reid. The two men actually met at a bar, and Prenter didn't become involved in Queen activities until much later than he did in the movie, as noted by Bustle.

The biggest dramatic inaccuracy in the movie, though, is that Live Aid was in no way a last-ditch Queen "reunion." They were still touring and rehearsing together normally in the lead-up to the event.

Bohemian Rhapsody favors Roger Taylor and Brian May's point of view

As one of rock's most famously bickering bands, Queen's story might be different depending on who you ask. The writers of Bohemian Rhapsody asked Roger Taylor and Brian May. The drummer and guitarist's involvement in the movie was so hands-on, it prompted originally-attached star Sacha Baron Cohen to quit. According to Cohen (via The Guardian), there was even an original plan for Mercury's death to happen halfway through the movie, with the rest of it charting the way the remaining band members went "from strength to strength."

Taylor and May's proximity to the project might explain why, for example, it glosses over the fact that both members were already well into solo careers of their own by the time Mercury released his first solo album. And while Paul Prenter is by no means a beloved figure among Queen fans, the depiction of him as a villainous leech who corrupts Mercury and leads him astray seems highly indebted to May and Taylor's own opinions, as observed by Ultimate Classic Rock. Prenter's family has disputed this depiction, stating that he and Mercury were simply good friends who enjoyed the London gay nightlife together, that Mercury was already partying hard and taking drugs long before they met, and that Prenter never did such a thing as concealing the Live Aid invitation to keep Mercury away from Queen.

Cohen himself has stated that he understands Taylor and May's reticence about how to depict certain things, as "they wanted to protect their legacy as a band." This legitimate concern also seems to have factored into the scene where the band agrees, just before Live Aid, to put an end to writing disputes and always credit their songs simply to "Queen" going forward — in reality, they didn't start doing that until 1989's The Miracle.

Bohemian Rhapsody makes a mess of Freddie Mercury's personal life

For an ostensible Freddie Mercury biopic, Bohemian Rhapsody is seemingly unconcerned about being truthful to his life outside the tours and recording sessions. Although Mercury's family did indeed migrate to the U.K. to avoid the brunt of the Zanzibar Revolution, they didn't so much flee with just their clothes on their backs as relocate more-or-less comfortably with English passports and everything, per the Sunday Times.

In addition to exaggerating details of Mercury's relationship with Paul Prenter, the movie straight-up rewrites his relationship with eventual partner Jim Hutton. In the movie they become acquainted when Hutton is working as a waiter at one of Mercury's parties and the singer sexually harasses him, but the real-life Hutton was a hairdresser who met Mercury casually at a gay bar, according to Vanity Fair. He did rebuff Mercury's advances at first — simply because he wasn't interested, rather than because he wanted Mercury to "clean up his act" — but then they met again by chance at another gay bar a year later, and immediately started dating.

Finally, the movie drew a lot of controversy for fumbling Mercury's battle with AIDS. In Bohemian Rhapsody, Mercury begins to feel seriously ill while deep in the party life during the band's "split," and gets an official diagnosis as preparations for Live Aid are commencing, upon which he immediately tells Taylor, May, and bassist John Deacon. In reality, he wasn't aware he had AIDS until 1987, which was two years after Live Aid, and the rest of the band wasn't made aware of it until 1989, via E! Online.

Therefore, it would have been impossible for the disease to serve as a motivation for Queen's spectacular Live Aid performance, as it does in the film. Per Salon, this particular bit of revisionism has been called "flippant and cruel," "an insult," and "inexplicably perverse" by critics, who felt it advanced negative stereotypes and erased Mercury's true legacy in the global fight against AIDS.