The Untold Truth Of Wallace And Gromit

Wallace and Gromit is one of the unlikeliest movie success stories there is. Everything about it is profoundly specific to England — really, to Lancashire County — and yet it's beloved all over the world. Its humor is dry and subtle, and its stories are much slower-paced than its cartoon cousins, and yet it's mesmerized generations of kids. It's profoundly old-fashioned in both its setting and its low-tech stop-motion animation, but it's held up against all the space-age CGI its competitors pull out. What began as a no-budget student film is now a global media empire.

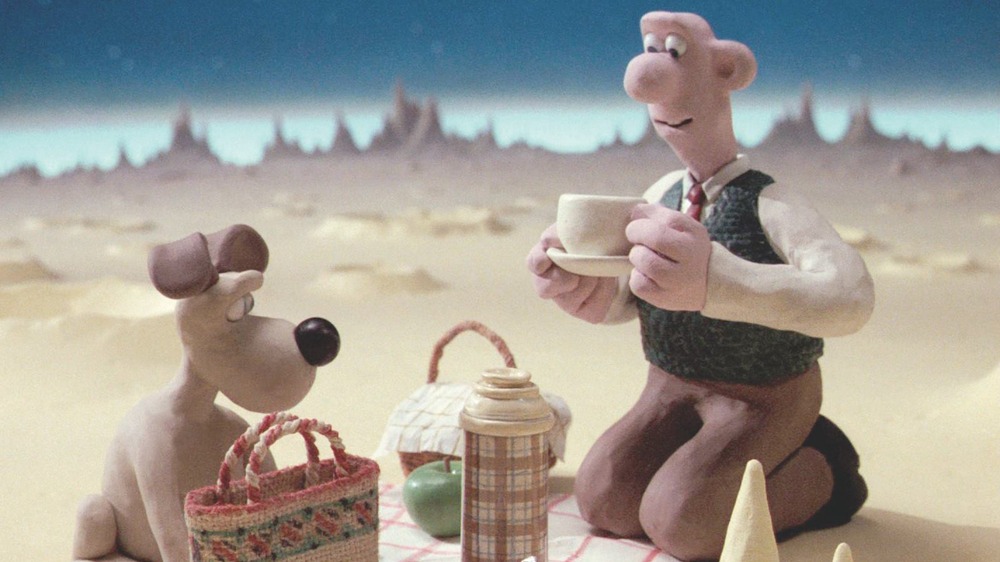

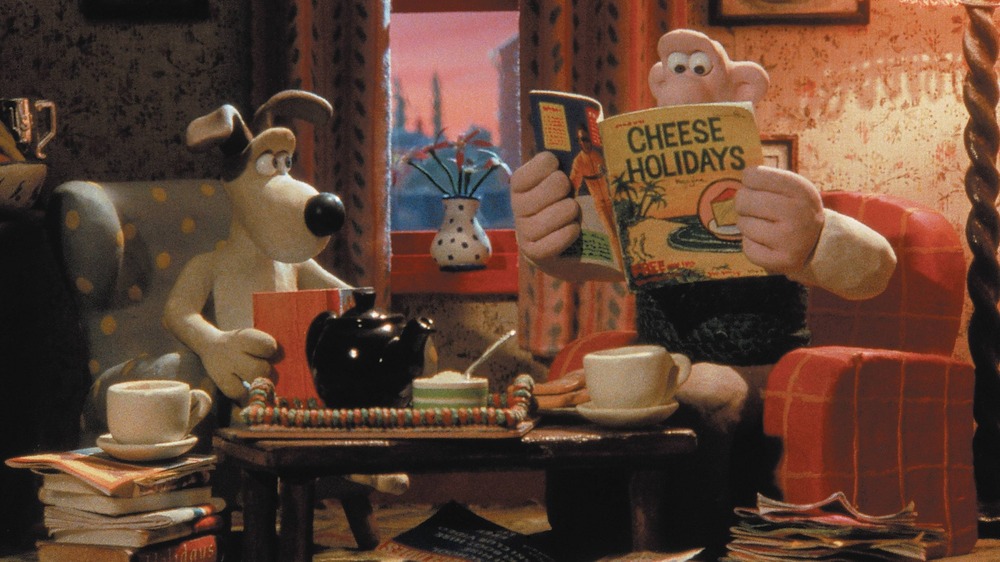

And through it all, Wallace and Gromit has never lost the heart of its title characters — Wallace, an addle-brained, amateur inventor, and his silent, longsuffering dog, Gromit, who says more with his eyebrows than most human actors can with the entire contents of the Oxford English Dictionary. Across four shorts (A Grand Day Out, The Wrong Trousers, A Close Shave, and A Matter of Loaf and Death) and a feature film (Curse of the Were-Rabbit), this comedy duo has built a body of work that most living, breathing stars could only dream of. But what went into the process of giving these little lumps of clay life and breath? Here's what we found out.

A Grand Day Out is based on a true story

There could be no Wallace and Gromit without Nick Park. In the early '80s, he had no idea he was creating a new multimedia franchise. He was just an art student working on his thesis film. That short eventually evolved into A Grand Day Out, where Wallace — stumped on a vacation destination — decides to build a rocket in his basement that takes him and Gromit to the moon. That sounds pretty out there, but Park says on his audio commentary for A Grand Day Out that he found inspiration close to home.

His father was a committed tinkerer who inspired much of Wallace's personality, and when Park was seven, his dad decided to build a caravan (what Yanks would call a trailer or camper). He bought an old one that was on the verge of disintegrating and built a whole new caravan on top of the chassis that Park describes as uncannily like Wallace's rocket, right down to the homey, kitschy wallpaper. "While animating [Wallace]," he says, "quite often, I could see my dad's face." On his commentary for The Wrong Trousers, Park is asked how his dad feels about being the inspiration for Wallace. Park says his old man loves it, but he makes sure to clarify that his real father is much smarter than Wallace.

Gromit was almost a cat

Even more than Wallace, everyone loves Gromit, the loyal dog we all wish we could have on our side. But Park revealed in the documentary A Grand Night In: The Story of Aardman that Gromit owes his existence to laziness. "I was thinking [Wallace] may have a pet," he says, "probably a cat. ... But as soon as I started making the clay model, a dog just was easier to make."

Gromit has earned praise for the subtle expressiveness of his "performance," able to convey every possible emotion with facial expressions alone. And that's with only half a face since his mouth is never visible. That takes a lot of hard work and talent, but Gromit's silence also started as an easy out. Park confessed to The Telegraph, "I recorded [British voice actor Peter Hawkins] as Gromit for a morning ... but when I tried to animate this it was too difficult, so I actually found that I could use Gromit's eyebrows to do all the speaking instead."

And if it weren't for a camera position in one shot, Park may never have discovered the possibilities in those eyebrows. Park shot Gromit from above in the scene where he fills in for Wallace's broken sawhorse. His mouth was invisible from that angle, so the eyebrows had to fill in, which led to a revelation: "Gromit's character grew from that moment. The brow shows how less is more."

How Wallace and Gromit got their names

With the characters' roles all set, all they needed were some names. "Wallace" may seem like an odd name to American viewers, and "Gromit" probably sounds odd to just about everybody. But each name has a story behind it.

Gromit isn't traditionally a name — it's a piece of hardware (actually spelled "grommet"), a rubber or plastic ring used to connect or support other materials. Park picked up this little bit of vocabulary from his brother, who was studying to be an electrician, and he told the Sunday Times it stuck with him enough to bestow on his animated dog. Why? "For me, it's always the way a word feels or makes a mouth move."

As for Wallace, Park tells the story in the same interview: "In an early version, Wallace was a postman called Jerry. Jerry and Gromit just doesn't have the same ring. But then I remembered this old lady on a bus in [Park's hometown] Preston. She got on with a fat Labrador called Wallace, and it struck me as a funny name, a very Northern name to give a dog." Or an amateur animated inventor, it would seem.

If the name Preston sounds familiar, it's because that inspired a Wallace and Gromit character too — the evil bulldog (or, as we learn in the last-act reveal, "cyberdog") who plays the villain in A Close Shave.

Wallace and Gromit changed from clay to cardboard for one shot

In case you're unfamiliar with the technique, Nick Park creates his Wallace and Gromit cartoons in stop motion (sometimes called claymation). This means he has to animate his clay models one frame at a time, and since the average film reel contains 24 frames every second, this means it takes a long time to painstakingly move and remold the clay characters one little bit at a time, snap a photo, and then move on to the next frame.

It's a long, difficult, and expensive process, so it may not surprise you to learn that penniless Park mixed it with a few other techniques for A Grand Day Out. He reveals on the audio commentary that one shot of the fuse burning for the rocket is a real fuse that's really burning, with Park snapping photos of it a couple times a second. He obviously couldn't use a real flame for a later shot of Wallace lighting a match, and clay wouldn't look quite right either. So if you look closely, you can see Park substituted cardboard instead.

You'd have to look very closely to catch it, but even Wallace and Gromit themselves turn to cardboard cutouts in one shot. After the rocket (also cardboard) lands, you can see Wallace and Gromit in the distance walking out of it along the moon's surface. Park explains he cycled through a series of five cardboard Wallaces and Gromits multiple times.

A Grand Day Out was a massive project

A Grand Day Out is still beloved over 30 years after its 1989 release for its small-scale, handmade charm. But while it's true that it's small compared to the titanic CGI cartoons coming out of Hollywood, it was still a massive undertaking. According to The Telegraph, a ton of clay went into A Grand Day Out. And when we say "ton," we mean "ton." Park placed an order for one imperial ton (2240 pounds) of non-drying plasticine.

But the material cost was nothing compared to the time it took: six years. It was only half done when Park graduated, but fortunately, it was rescued by the Aardman animation studio. Park remembers on the commentary how one line of the script — "There now follows a building sequence where Wallace and Gromit build a rocket" — took a year and a half to finish.

Fortunately, Park had friends in high places. He asked British sitcom star Peter Sallis to record some dialogue for Wallace, but he could only pay £50. The actor only thought of it as a favor to a struggling student and then forgot all about it until he got a phone call six years later, telling him the project was done. It was definitely worth the wait, as Wallace made him a bigger star than his TV series, Last of the Summer Wine, ever did, and he continued playing the lovable Northerner until his death in 2017.

Body parts littered the floor at the end of each day's shooting for The Wrong Trousers

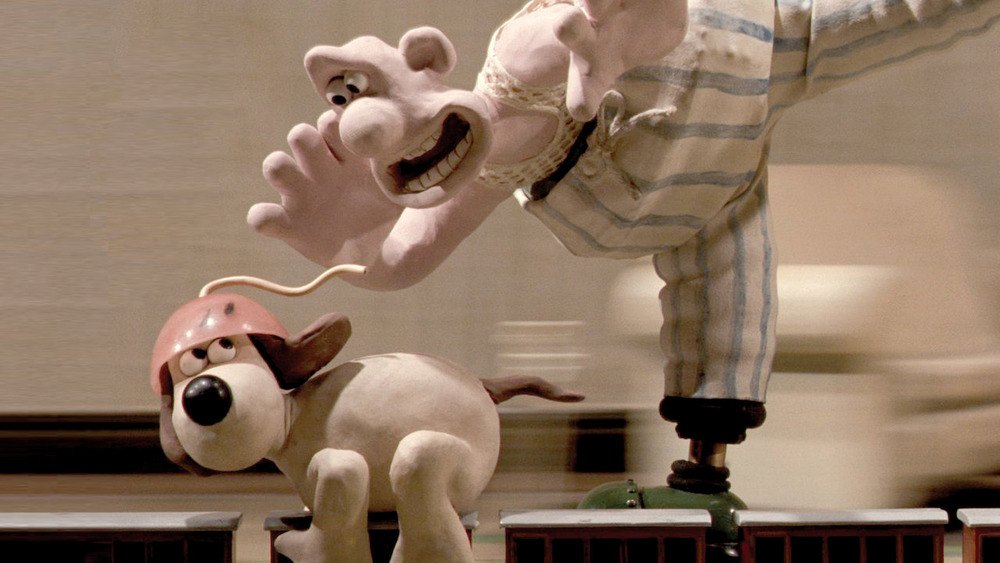

With the full power of the Aardman studio behind him, Nick Park went even more ambitious for his classic follow-up The Wrong Trousers. This short for BBC introduced Wallace's "techno trousers" and a crime-thriller plot involving his new lodger — a creepily silent, expressionless little penguin.

Things could get a little spooky in the studio too. To promote the film, Park appeared in the documentary Inside the Wrong Trousers. In this behind-the-scenes peak, viewers get to see the animator at work. Park starts getting Wallace to talk, but he finds that the model's teeth are too big to open the mouth wide enough, so he pries them out. Apparently, this is all part of the job, as Park explains, "I keep dropping tongues and eyelids down in front of the characters, under the table where it's inaccessible. So at the end of a day's shooting, you can find all the eyelids and stuff under the table."

Nick Park encouraged his animators to leave their fingerprints on their work — literally

Aardman gave Nick Park a whole team to work with at a big, professional studio, and as Wallace and Gromit's success grew, so did the resources available to him. But he understood that people love his shorts not for the flawless illusion of reality so much as the handmade charm he developed when he had fewer hands to work with. And he's been sure to keep that up no matter how big Wallace and Gromit gets.

Most studios would try to avoid the little imperfections that pile up working with clay to make the characters look as much like real people as possible. But that's not Wallace and Gromit's way. Park told the Los Angeles Times that he tried the more polished approach on his first feature, Chicken Run. "We were worried that stop-motion and the fingerprints we left on the clay would look too big on screen. We were worried that some of the action might look jerky. So we put a lot of attention toward smooth movements on the screen."

But that all changed when he returned to his first creations. ABC reported that Park regretted all the spit and polish he put into Chicken Run, and his producer, Peter Lord, explained why he went back to basics, saying, "You can see the fingerprints. It tells you that they are real. They are tangible." And in a time when most cartoons only exist behind a computer screen, that gives Wallace and Gromit an edge on their competition.

Dreamworks didn't totally get Wallace and Gromit

With their feature-length film, Curse of the Were-Rabbit, Wallace and Gromit went Hollywood, working once again with their Chicken Run distributors at Dreamworks. The result shows the team at their best, with a parody of horror films that's both hilarious and genuinely thrilling in its own right, maybe because its parody status lets it go over the top in ways more serious movies would be afraid to. Curse of the Were-Rabbit works like a well-oiled machine, which is all the more impressive because it was anything but behind the scenes.

The Aardman crew frequently found themselves butting heads with Dreamworks producer Jeffrey Katzenberg. He knew people loved Wallace and Gromit, but some of his suggestions make you wonder if he knew why. For example, Park told The Telegraph that Katzenberg couldn't understand why Wallace had to drive a clunky old car and asked the animators to give their icon of uncool a trendy new model.

Park had the clout to keep Wallace's car Wallace-y, but the studio won out on the title. According to The Guardian, Aardman originally pushed for the punnier title of The Great Vegetable Plot, but Dreamworks wasn't having it. "Market research didn't like it," Park says, "The verdict was that 'vegetables are a negative with kids."

The Mind-o-Matic originally came from the KGB

Curse of the Were-Rabbit pits out heroes against, well, a were-rabbit, which is ravaging the vegetables of their little village. It all turns out to be Wallace's own doing thanks to his latest bit of gadgetry, the Mind-o-Matic, which he uses for a "bit of harmless brain alteration" on some captured bunnies.

The final film leaves it up to the audience to assume Wallace built the device himself, but according to the audio commentary by Park and co-director Steve Box, Aardman was considering a much more darkly funny origin story. Just as Wallace claimed the techno-trousers were the latest from NASA, an earlier draft of Were-Rabbit would've shown him playing both sides of the Cold War divide when he receives a package from Russia, one that contains some ex-KGB brainwashing equipment.

The visuals of the Mind-o-Matic went through multiple incarnations too. Park describes his original conception as "a huge centrifuge that spun around." The proto-Mind-o-Matic stuck around through a good part of the creative process, making it as far as storyboards. Aardman even built a model of it before it took the form that made it to the screen as a hilariously improbable cranium-mounted glass globe with lightbulbs on either side.

The church sequence took a year to film

Curse of the Were-Rabbit was far bigger than anything Wallace and Gromit had ever done before, not just in terms of stakes and running time but in cast too. The short films had only shown us bits and pieces of the characters' world. Up until Were-Rabbit, we only ever saw one human character besides Wallace. The movie expanded the characters' universe exponentially, now with a whole village full of zany characters, some with celebrity voices like Ralph Fiennes and Helena Bonham Carter.

That was a massive undertaking for a film that required Aardman to build each character by hand and move them one little bit at a time. And it was downright daunting for the town meeting in the church following the were-rabbit's rampage, which required nearly every character to be on-screen at once. The commentary recalls that this one four-minute sequence took an entire year to film across multiple sets. It was filmed out of sequence, with each of the characters ("50 or 60" by Box's count) constantly moving — he says the animators needed to keep charts just to keep them all in the right place. "It was quite a thing to keep tabs on them all," he says, and we have to imagine that's an understatement.

The Wallace and Gromit crew went to fine art for inspiration for the greenhouse scene

Curse of the Were-Rabbit is packed tight with references to some of the all-time great horror movies, from Jaws to King Kong to more generalized clichés of the genre like the skeptical policeman and the old priest with a knowledge of the occult. But sometimes the animators got a little more highbrow.

In one scene, local aristocrat Lady Tottington seduces Wallace by taking him into her rooftop greenhouse. During this scene, Park says on the commentary, "[Director of photography] Dave Riddett and I ... we looked at lots of postcards and prints of pre-Raphaelite paintings. You know, with these women in these fantastic silk dresses, playing flutes surrounded by plants with a sunset behind them."

He's referring to the 19th-century art movement founded by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais, and others, applying the principles of the literary Romantic movement to art. The artists took their name from their rejection of what they believed to be the decadent influence of the Renaissance painter Raphael, reviving the stylized compositions and bold colors of Medieval art. Those colors certainly come through in the movie, but Park can't resist bringing it back to a more lowbrow point of view: "It reminds me of The Empire Strikes Back as well!"

Aardman recreated Wallace and Gromit's world for visitors to London and Blackpool

Aardman has created such a cozy, welcoming world in the Wallace and Gromit movies that millions of viewers have probably wished they could enter into it in real life. That's not actually possible, but there are two locations in the UK that offer the next best thing. In 2009, the London Science Museum opened an exhibit called "A World of Cracking Ideas." Along with true stories of young inventors and offbeat inventions, the exhibit included a perfect recreation of Wallace and Gromit's home, a slide that takes little visitors into the garden, and working replicas of some of Wallace's wacky contraptions — to the extent anything Wallace builds can be said to "work."

"A World of Cracking Ideas" was, as the Muppets' Beaker might say, sadly temporary. But fans can still take a look around Wallace and Gromit's world at Blackpool Pleasure Beach, a seaside resort fittingly located in the characters' birthplace of Lancashire. In 2013, the park refurbished their Gold Mine ride as Wallace and Gromit's Thrill-o-Matic. Much like Disneyland's "dark rides" (Snow White's Scary Adventures, Peter Pan's Flight, etc.), this ride takes visitors on a tour through memorable scenes from all five Wallace and Gromit films in cars shaped like Wallace's cozy slippers. Highlights include a tunnel where bucktoothed rabbits peek down from the surface, an entrance featuring a gallery of the duo's family photos, and the exit, where riders are menaced by a giant were-rabbit.