The Untold Truth Of The Wizard Of Oz

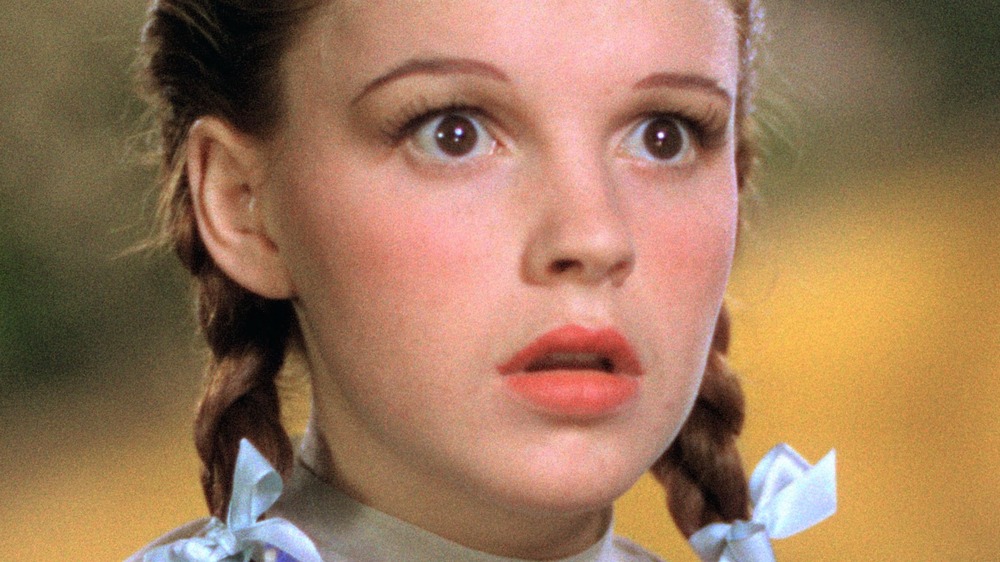

There's no place like home, and there's no movie like The Wizard of Oz. From its delightful cast and eye-popping Technicolor to memorable songs like "Somewhere Over the Rainbow," nearly everything in this film is perfect. Over 80 years later, many of the special effects still hold up. Sure, the vultures in the haunted forest may look like the kind of thing you'd see at a modern Spirit Halloween, but The Wizard of Oz will still make you believe a sock is a tornado and Ray Bolger is really made of straw. The comedy is razor-sharp, the dramatic moments can make grown men cry, and the script as a whole is the most quotable one ever written.

The classic story of a Kansas farm girl dropped off in the magical land of Oz is an inseparable part of American culture and the earliest memories of over four generations of children. Everything in The Wizard of Oz works so smoothly that it's hard to believe it had anything but an easy — possibly yellow brick — road to theaters. But the movie barely came together at all. Here are just a few of the strange stories from the The Wizard of Oz's difficult path to completion.

There's plenty more where the book came from

Even before The Wizard of Oz became a movie classic, it was already a huge part of the American cultural landscape. For that, you can thank L. Frank Baum, the author of the original novel. And if you watched Dorothy leave Oz and wished you could stay, we've got good news. Baum wrote 14 Oz books that he tied into the Oz universe.

In addition to Dorothy and her famous friends, Baum's sequels feature all sort of colorful characters and locations, many of them based on suggestions from his young readers. There's a sawhorse that comes to life so the heroes can ride him like a real horse. Then we've got the Nome King, an evil monarch who looks and acts like jolly old St. Nick. Plus, there's Fuddlecumjig, a town of jigsaw puzzle people. That's not even mentioning Princess Langwidere, who keeps a collection of spare heads, or Quox, a bug-eyed dragon with rows of seats on his back. If some of these characters sound familiar, it may be because they appeared in the cult classic Return to Oz.

Even after Baum's death, the series continued under the pens of Ruth Plumly Thompson and others. Altogether, there are 40 "official" Oz books — and even that barely scratches the surface — with even more being written after Baum's creation entered the public domain in 1956.

The Tin Man met a man made of his old body parts

Baum's introduction to The Wonderful Wizard of Oz says, "The time has come for a series of newer 'wonder tales' ... with all the horrible and blood-curdling incidents ... eliminated." But it's debatable whether or not Baum succeeded in defanging his fairy tales. Oz and its sequels are so violent they're barely kid-friendly at all by modern standards, and as Baum let his surreal imagination loose, he came up with some truly blood-curdling nightmare fuel.

In the movie, it seems the Tin Man is just another of Oz's unexplained magical phenomena, but the novel gives him a gruesome origin story. He used to be a flesh-and-blood woodsman named Nick Chopper until he fell in love with the Wicked Witch of the East's daughter. The Witch didn't want her to leave home, so she enchanted Nick's ax to chop off his body parts one by one, and he replaced them with tin until none of his original self was left.

That brings up some disturbing existential questions that only get more horrifying in The Tin Woodsman of Oz. In Chapter 18, "The Tin Woodsman Talks to Himself," he returns to the tinsmith who rebuilt him and finds his own head in the cupboard. Even more disturbing, the Tin Woodsman meets Chopfyt, the tinsmith's assistant made of spare parts — stuck together with "meat glue" — from Nick and another character named Captain Fyter who met the same fate.

The Wizard of Oz's first draft was a conflict between jazz and opera

One of the many kids who grew up with The Wizard of Oz was songwriter and future musical superproducer Arthur Freed, who both wrote "Singin' in the Rain" and produced the movie of the same name, along with Meet Me in St. Louis, Gigi, and many of the other classic musicals of the era. According to The Making of the Wizard of Oz, he pushed MGM to buy the rights for his first producing job on the classic Judy Garland film. The studio agreed, but for insurance, they put the more established Mervyn LeRoy in charge and let Reed work as his assistant.

Now that they had the book, MGM had to decide what to do with it. You'd think Baum's plot would be enough, but Hollywood loves to fix what ain't broke. The Wizard of Oz: The Official 50th Anniversary Pictorial History runs through the many drafts of the script, most of which gave a lot of page time to a totally new character — Sylvia, the princess of Oz — who would've had a romantic subplot with the Cowardly Lion, who was really an enchanted prince. The role was written for opera singer Betty Jaynes, with the idea of using her rivalry with jazzy Judy Garland to play out the conflict between old and new styles of music. That subplot went out by the time filming started, though Jaynes and Garland still faced off in another movie that year, Babes in Arms.

MGM considered using real and animated lions

On the page, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz was limited only by Baum and illustrator W.W. Denslow's imaginations. The movies, especially in that prehistoric age of special effects, created more challenges. One of the biggest ones was how to create a talking, singing Cowardly Lion.

Historian John Fricke's audio commentary for The Wizard of Oz details some of the odder solutions that producer Mervyn LeRoy contemplated. Maybe LeRoy was anticipating the current era of CGI when he suggested dropping an all-animated lion into his live-action movie. He also suggested using a live lion and dubbing in dialogue over it. And in The Wizard of Oz, even the big cat had to be a star, as the plan was to use Leo, the lion who appears in the MGM logo.

Fortunately, the studio went with vaudeville comedian Bert Lahr in his lion suit instead. The idea of going to the real thing didn't quite go away, though — that suit is made from genuine lion skin.

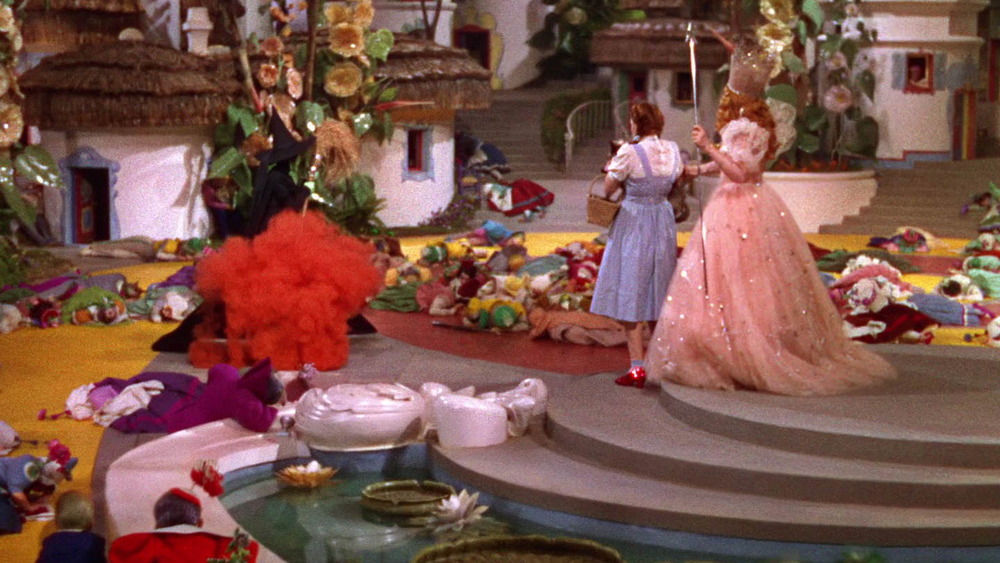

When Dorothy enters Oz, you're seeing some amazing movie magic

The Wizard of Oz was 1939's equivalent of the modern-day special effects spectacular, but the effect that's stuck most in the collective consciousness is also one of the simplest — when Dorothy leaves the sepia-colored world of Kansas and enters the Technicolor Land of Oz.

Look closely next time you watch that scene. To make the effect as shocking as possible, Dorothy herself has to be sepia-colored as she opens the doorway, and she only turns Technicolor once she enters Munchkinland. You might think this was some complicated post-production effect with mattes and optical printers and whatever else passed for high tech in 1939. But in his audio commentary, historian John Fricke explains it was actually as simple as you could imagine. When Dorothy opens the door, that's actually Judy Garland's stand-in wearing gray makeup and a gray version of Dorothy's iconic blue dress. (Even the Kansas set is painted.) Then she ducks offscreen, and the real Garland comes back out in her colorful dress and walks into the colorful world outside.

Many of the Wizard of Oz actors are lucky to be alive

The Wizard of Oz is so joyful you have to imagine that was the mood behind the scenes ... but it was just the opposite. If anything, it sounds like it was an ordeal.

The Technicolor process required enormous incandescent lights that heated the studio hotter than the sun. And then there was a makeup mishap that led to an actor being replaced. According to The Wizard of Oz: The Official 50th Anniversary Pictorial History, former vaudeville and future TV star Buddy Ebsen was first in line for the Tin Man. The aluminum-dust based makeup coated his lungs and nearly killed him. As you'd imagine, he never wanted to do that again, so the role went to Jack Haley — with new, less deadly makeup.

Then, Margaret Hamilton's exit from Munchkinland as the Wicked Witch required her to descend in an elevator as smoke and flames shot out of the floor. But the elevator wasn't quite fast enough, and the copper-based makeup on her face and hands caught fire. Naturally, Hamilton wanted nothing to do with smoke or fire after that, so her stunt double covered for her when the Witch writes "surrender, Dorothy" in smoke in the sky. According to John Fricke's audio commentary, Hamilton was right to worry — the broom literally exploded under her stand-in. Then there are the flying monkeys ... two of them fell out of the air when their support wires snapped in mid-flight.

The Scarecrow was literally left hanging

Ray Bolger's song and dance for "I Only Had a Brain" is one of The Wizard of Oz's highlights, and there was originally even more of it. According to historian John Fricke, MGM brought in the legendary, revolutionary musical choreographer Busby Berkeley to add an even more elaborate dance solo to the sequence, including one moment where the Scarecrow flies through the air. Millions of dollars later, MGM decided to cut the scene.

But the stars of Oz suffered for their art, even if it never made it to the screen. Bolger was in the middle of said flying scene when the whistle blew for lunch. The whole crew promptly packed up and went on break — including the guy holding Bolger's rope, leaving him stuck in midair until the working day resumed. Then again, we can't really blame the stagehands. Any excuse to get out from under those scorching lights sounds like a good one.

The Scarecrow got attacked by a crane

Everything in The Wizard of Oz was filmed inside the MGM studios, but the filmmakers did what they could to make their stage-bound sets look real. According to Fricke in his Wizard of Oz commentary, that included filling the forest where Dorothy meets the talking apple trees and the Tin Man with live birds on loan from nearby Los Angeles Zoo Park. One of them chilling out indistinctly in the background inspired persistent rumors that if you looked closely, you could see a suicidal starlet, or possibly a Munchkin, hanging from one of the trees.

That Hollywood legend was years away, but the birds caused some more immediate problems on the set. A crane spotted the straw hanging from Ray Bolger's Scarecrow costume and, thinking it looked like good eating, chased him around the studio. Once he got away, Bolger had to keep out of sight, and shooting stopped dead while the animal wranglers calmed the bird down.

The voice of Snow White makes a cameo

According to The Wizard of Oz: The Official 50th Anniversary Pictorial History, a big reason MGM gave the green light to The Wizard of Oz was the enormous success of Walt Disney's 1937 musical fantasy, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. The filmmakers weren't shy about their inspiration either. Their first choice for the Wicked Witch was glamorous star Gale Sondergaard, and instead of the grotesque terror that made it to screen, they envisioned her as a beautiful witch like Snow White's stepmother, right down to the hair-covering head scarf.

That never happened, of course, but an even more concrete connection did make it to theaters. During his performance of "If I Only Had a Heart," the Tin Man imagines himself as Romeo, and the disembodied voice of Juliet pops in to ask, "Wherefore art thou, Romeo?" And as it turns out, that voice belongs to Adriana Caselotti, the voice of Snow White.

Two other veteran Disney players make uncredited appearances of their own as singing voices for some of the Munchkins. That's Pinto Colvig, whose roles include Goofy and Snow White's Grumpy, and Billy Bletcher, with the deep, booming voice he used as the Big Bad Wolf and Peg-Leg Pete sped up all the way to the other side of the scale.

The story of L. Frank Baum's coat

MGM wanted an all-star cast, but they had trouble getting the big names they wanted for the small but pivotal role of the Wizard himself. Two of the biggest comedy stars of the time, W.C. Fields and Ed Wynn (Disney's Mad Hatter), turned it down because it was too small. Then the filmmakers hit on a solution — beef up the part with additional roles. That's how they got Frank Morgan to play the Wizard, along with the gatekeeper, the cabbie, the guard to the Wizard's inner sanctum, and Professor Marvel.

The Official 50th Anniversary Pictorial History quotes publicist Mary Mayer, who says, "For Professor Marvel's coat they wanted grandeur gone to seed. ... So the wardrobe department went down to an old second-hand store on Main Street and bought a whole rack of coats." Morgan sorted through them with the costume department and director Victor Fleming to pick just the right one. One day, Morgan noticed a name sewn into the pocket — L. Frank Baum, the Wizard's creator.

This story was dismissed for years as a lie dreamed up for publicity, but since then, both cinematographer Hal Rosson and his niece, Helene Bowman, have come out to confirm it. We think historian John Fricke sums it up best: "If it isn't true, it ought to be."

The final edit created some plot holes

Even when The Wizard of Oz was done, it still wasn't done. The rough cut ran just over two hours, which might seem short by today's standards, but it was much too long for 1939. So a whole lot of footage ended up on the chopping block.

Poor Margaret Hamilton got hit the worst — her performance was so effective that crying children had to be dragged out of the test screening, so she lost whole pages of child-traumatizing dialogue. But somehow, one puzzling line stayed in — "I sent along a little insect to take the fight out of them." She did? Well, yes, but only in the rough cut. That included a musical sequence where the Witch's Jitterbug bit Dorothy and friends, giving them "the jitters." The producers rightly predicted a long sequence based on a current dance fad would date the movie, so out it went after five whole weeks of rehearsal and shooting.

There's a subtler plot hole in the Emerald City. When the guard goes to see the Wizard, he has a long mustache that curls up. But when he comes back, his mustache hangs down. That's not a mistake. In his audio commentary, John Fricke says it was originally the setup to a joke about the changing of the guard. But since the punchline's missing, it's just another inconsistency for trivia-heads to point out.

TV made The Wizard of Oz a classic

It's strange to think now that it's become the most beloved movie of its time — maybe even all time — but The Wizard of Oz actually lost money on its initial release. True, by most standards, it was a huge success, ranking second in the year-end box office tallies. But the unprecedented cost of its making and marketing, as well as its appeal to children (who didn't pay full price for their tickets) put it in the red.

A classic like this was probably never going to be forgotten, but its afterlife on TV made it into a landmark. The Wizard of Oz: The Official 50th Anniversary Pictorial History records how, at first, MGM kept Oz and other prestigious properties out of the packages it sold to local TV stations. But in 1956, MGM finally caved and sold the rights to CBS, who went all out, filming a new introduction with the Cowardly Lion himself, Bert Lahr, and Judy Garland's little daughter and future musical superstar Liza Minnelli.

It was a huge success. While it was on, over half the TV viewers in America were tuned in. Soon, The Wizard of Oz became an annual event — even if many viewers didn't get what made going over the rainbow so special since they saw the whole thing in black and white. Still, it never got less than half the viewing audience throughout the '60s.

The US Navy tried to interrogate Dorothy

Everybody loves The Wizard of Oz, but no one loves it more than the gay community. The effusively campy story of a misfit teenager escaping her small-town home to find a new family of fellow outcasts on the other side of the rainbow resonated so strongly that "friend of Dorothy" has become synonymous with "gay."

Not everyone was hip to the lingo, though, at least not in the US Navy. According to Today I Found Out, in the 1980s, the brass was on a mission to hunt down and expel all its gay servicemen from their base in the Great Lakes. Noticing how many of these sailors identified themselves as friends of Dorothy, these geniuses decided they needed to find this mysterious woman so she could inform on all her "friends." Soon, the Navy was sending investigators to every gay bar in the area to find information on Dorothy, presumably while their interviewees tried very hard not to laugh their butts off. All these years and millions of taxpayer dollars later, they still haven't found her, but we have to hope they've at least found out they've been chasing a fictional character.