19 Mind-Bending Movies Like Inception

Christopher Nolan's 2010 sci-fi noir Inception is a dream movie (literally) for film buffs who love to have their minds bent by what they watch. But Inception will bend more than just your mind: It's famous for its topsy-turvy visuals, in which entire cityscapes twist and turn upside down before our eyes in a world of manipulated dreams whose outcomes affect reality.

Films like Inception bring up all kinds of questions — not just with their often confusing endings, innovative premises, and unconventional plot structures, but with the concerns they raise about how the mind (and even the universe) work. Fans of Inception will have a blast with the many films that have a lot of the same features as Nolan's instant classic. Because just about all of Nolan's other features also fit the bill and could secure a monopoly on this list, they aren't included. But suffice it to say that his entire filmography, from The Prestige to Memento, Interstellar to Tenet, is worth watching if you enjoyed Inception.

All of the following non-Nolan films poke at the nature of reality, especially to what extent it's manufactured by our own minds or worse, by forces outside of our control. And like Inception, there are action, sci-fi, and noir elements to most of them, while a few are more abstract, just like the world of dreams. So whatever you loved about Nolan's dreamscape, you just might find it in one of these films as well.

Do you dream in Upstream Color?

In 2004, Shane Carruth bewildered audiences with his debut Primer, a micro-budget sci-fi film with a dizzyingly, almost infuriatingly complex time-travel plot that has spawned countless discussions and diagrams across the internet. Carruth, a mathematics major, didn't spare the audience any of the technical jargon used by the characters around physics and time travel, which only elevates the confusion — and the authenticity.

For his second film, Carruth went in nearly the opposite direction: Many of the scenes in 2013's Upstream Color don't have much dialogue at all, relying instead on an "absorbing" sound design that won the Grand Jury Prize at the Sundance Film Festival for its "incredible aural inventiveness." Because of the immersive sound and ethereal visuals, much of this film feels like a dream.

Its plot only contributes to this effect by meandering through the lives of people and animals who appear to be linked across time and space by an unknown force that pulls the strings. If one of the things you liked about Inception was the tickle of your mind trying to solve a puzzle in a world that doesn't seem quite real, this is definitely a film for you.

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind is a timeless take on romance

Memory, a central theme of 2004's Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (written by surrealist legend Charlie Kaufman and directed by Michel Gondry), sometimes occupies a space between reality and unreality. And all of that gets even blurrier when you start meddling with someone's memories, like the protagonists of the film, Joel and Clementine, a couple who has decided to erase their memories of each other.

Anyone who's ever dealt with a failed relationship can probably identify with the desire to just delete that experience from memory. By erasing their memories, though, Joel and Clementine create their own sort of false reality: A lie by omission is still a lie, as countless parents have warned.

But Eternal Sunshine's plot gets more complicated still when Joel, in the midst of his procedure, decides he doesn't want to forget Clementine. In order to preserve her memory, he begins modifying his own memories by "hiding her" in past experiences that didn't actually involve her. (It would be great if this worked for car keys.)

Like Inception, this cult classic teaches us how difficult it is to attempt to control the subconscious, or to separate it from the physical, conscious world. The best way to do this is not by trying to change or undermine what we experience, but to accept it — good, bad, and ugly.

Gattaca is a true case of mind over matter

In the dystopian future of 1997's Gattaca, "be your own man," as the dream projection of Cobb's father instructs him in Inception, isn't really an option. With the advent of commonplace genetic selection, any traditionally conceived individual is viewed as defective, more prone to disorder and disease and "in-valid" for advanced positions in career and society. The main character, Vincent, makes it into an upper-echelon space program by the skin of his teeth — or more accurately, by someone else's skin entirely.

It's stressful enough that in order to pass for valid, Vincent must meticulously scrub off evidence of his own DNA every day in order to pass for the genetically superior man whose DNA he's actually using. But that level of tangled tension is only the beginning. Vincent must navigate everything from class discrimination to murder in order to cling to the life he's built.

Both Inception and Gattaca observe the meticulous undertaking of creating your own reality and identity, with all of the moving pieces involved. But what appeals most to fans about both is probably the combination of science fiction and action that forces us to question how sure we really are of our place in the world.

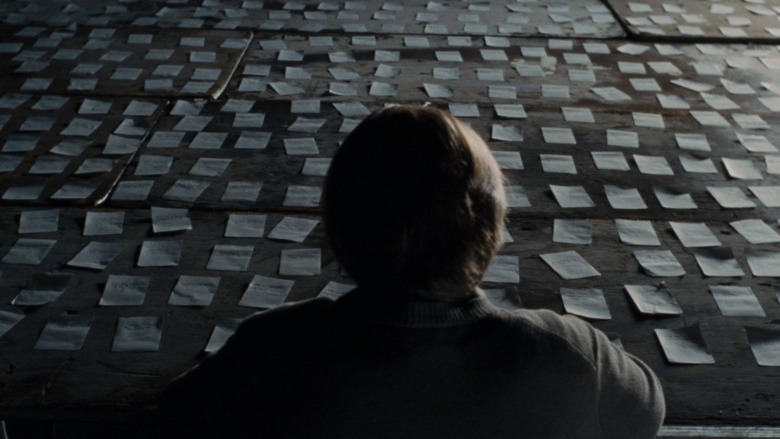

Under the Silver Lake takes a deep dive into urban legend

While on one hand Inception has become something of the mainstream vanguard of "confusing movies," Under the Silver Lake had all the makings of an underrated cult classic when it came out in 2018, complete with polarized critical reviews that either lauded its originality or wrote it off as too cryptic (which, a true fan might argue, is a testament to originality in itself).

Plausibly very much like the film's target audience, its protagonist Sam, portrayed by Andrew Garfield, is a shiftless early-thirty-something who is more interested in the hidden meaning behind everyday occurrences than in meeting adult obligations. But a directionless protagonist couldn't be a more perfect fit for the plot of Under the Silver Lake, which soon takes off in all kinds of directions. Down these roads, Sam meets a series of seemingly interconnected characters that appear to be straight out of urban legend.

The film is abundant with conspiracy fodder, making it engaging (and amusing, in its own darkly humorous way) whether or not you're inclined to analyze it any deeper. If you choose to take the dive, you might resurface anywhere from the halls of the Hollywood elite to a cult's underground bunker.

Donnie Darko illuminates a mad world

As famously confusing as Inception is, pretty much all the puzzle pieces are right there in front of you — you just have to assemble them in the right order. This is much less the case in the infamously cerebral 2001 film Donnie Darko, which requires some pretty extensive background knowledge (and probably multiple viewings) to begin to understand what's really going on.

For example, it might not even be apparent at first blush that in addition to being another time travel movie (this premise operates much more on a subsurface level than in films like Looper), Donnie Darko is also a superhero movie. In order to understand any of that, you'll need to get yourself a copy of The Philosophy of Time Travel, offered to Donnie by his science teacher. The book doesn't exist in our world, really, but you can find it on the director's cut DVD.

Once you understand the intricate rules of the parallel universes that operate in Donnie Darko, what seem like a bunch of random occurrences actually make a ton of sense. Every single character and event serves a purpose, even — especially — a jet engine falling from the sky. So how is it a superhero movie? Because at the center of these parallel universes is Donnie Darko, the only one who can prevent cosmic annihilation. If you liked the layers of Inception, you've got to watch Donnie Darko — then watch it again.

The Matrix is everywhere

If you were so inclined, you could think of the Matrix trilogy as a "reverse" Inception (down to its strikingly similar visuals): Instead of going into dreams, the trilogy begins with removing us from a non-reality and exposing it for what it is.

To quote Morpheus in the 1999 film that started it all, "The Matrix is everywhere." This statement is true in the world of the film, in which the Matrix constructs reality, and it's true in the modern entertainment industry, where its influence can be felt throughout TV and cinema, and reruns can be caught almost weekly on cable.

As in Inception, much of the action in The Matrix takes place in a shared subconscious world. However, it's not just the subconscious influences of each participant that Neo and his comrades have to contend with: the Matrix itself is defended by its own Agents, AI programs whose sole purpose is to take out anyone or anything who might threaten the simulation. Someone who knows it's a simulation, for example, presents an enormous threat to the system.

The conflict in The Matrix, then, much like Inception, is waged on two fronts, the subconscious and the real. But the consequences of actions in either realm can have direct effects on the other, creating the kind of intense sci-fi pressure that fans of either film will love.

Mulholland Drive is a 'crash course' in surreal noir

Though the intriguing psychological premise often takes center stage, Inception is definitely something of a noir, which means that fans of the film will certainly love David Lynch's trademark marriage of intrigue and surrealism in the 2001 film Mulholland Drive. Not the first film on this list to deal with the "memory" aspect of psychology, this mystery opens on a woman suffering from amnesia after surviving a car crash.

Right from the start, we're forced to accept that there's a lot of information being withheld from us and everything may not be what it seems. Indeed, according to the emcee at Club Silencio in the film, everything is an illusion. But rather than a sci-fi basis for such illusions as with Inception and many similar films, Mulholland Drive executes illusions (and delusions) with Lynch's convoluted storytelling style and the fragile psychology of the characters.

With Lynchian trademarks like ambiguity of identity, murder and mob ties, surreal connections, and the influence of dreams, Mulholland Drive — as different as it is from Nolan's film — is sure to entrance Inception fans.

Eyes Wide Shut will open yours

If you've ever had a night when you had one strange dream after another with the vague feeling that they were all connected somehow, then you have a clue of what you're in for with the mood of Eyes Wide Shut, which follows Bill, played by Tom Cruise, through a series of bizarre encounters around New York City. Like many of Stanley Kubrick's works, this 1999 film has the ethereal quality of a dream.

But even if you're prepared to drift from one vignette to another, nothing we could say will really prepare you for the strange things that happen in each one. It's an erotic psychological mystery, but that doesn't simply mean that everyone is walking around naked: Characters appear in costume (for various reasons) about as often as they appear nude. The continuous shots in these scenes makes each feel like a self-contained world.

From secret societies to costume shops, the most important character in this movie is the stranger — because there's a stranger in everyone you meet, from the spouse you've known for years to the anonymous allure of a masked sex worker or the vaguely familiar face in your dreams. The unknown is the basis of fantasy and eroticism, so the act of obscuring (metaphorically, closing your eyes) can actually be eye-opening. Following the thread of crime, mystery, and passion in Eyes Wide Shut is as enjoyable as it is in Inception.

Being John Malkovich is a 'heady' fantasy

With Inception, Christopher Nolan showed us what it's like to get inside someone's head. The 1999 film Being John Malkovich, another feature written by Charlie Kaufman, takes this premise a bit more literally. Instead of sneaking into their dreams while they're sleeping, in this fantastical comedy, characters actually inhabit, and in some cases control, another person's mind and body like a bizarre and invasive theme park ride.

The film isn't about John Malkovich just being himself, as you might first guess: It's about a series of other individuals being John Malkovich. The poor actor doesn't really get a lot of screen time "as" himself. Instead, he's a vehicle of fantasy. Much like our subconscious mind, whether awake or sleeping, can allow us to live out other, imagined realities, the grimy but supernaturally endowed tunnel that leads into John Malkovich's mind is an escape into another existence.

Characters use John Malkovich to escape from everything — their lackluster lives, their assigned genders, and even mortality itself. It's a step up from dreaming or fantasizing that shows us in absurd fashion why alternate realities are usually best left in our imaginations, and that no matter where we go, we can't escape our own minds (even inside someone else's head).

Fight Club's wake-up call

Even though we're not supposed to talk about it, that's exactly what critics and audiences did with Fight Club long after its 1999 release. Many were afraid of the legacy it would have, like the copycat issues following the release of A Clockwork Orange in 1971. The film certainly had its fair share of cultural impact, but this mostly consisted of quotability and influence on the entertainment industry — much like Inception or The Matrix.

Unlike similar reality-bending films that leave things more ambiguous, however, Fight Club's twist relies on clearly drawing the line between what's real and what's not — but only after leading the viewer completely astray first. And there's no sci-fi involved in this misdirection, just the subjectivity of an unreliable Narrator (as the main character is known) who tells us the story of his volatile new "frenemy" Tyler Durden.

From the start, the Narrator reveals that he can't always be trusted, adopting different aliases and posing as a sufferer of various diseases in the hopes of getting support for his chronic insomnia. In a way, this early introduction gives us all the information we would need to guess at the ending — but we're in the Narrator's reality, not ours, so we have to wait to see it unfold.

Funnily enough, the Narrator is not misleading us on purpose: The crucial elements of the story happen when he believes he's sleeping. Hear that, Inception fans?

Looper closes the deal

In addition to a deftly layered premise, Inception shares another quality with the highly acclaimed 2012 time travel film Looper: A principal cast appearance by Joseph Gordon-Levitt. In Rian Johnson's high-test sci-fi thriller, the actor portrays a hit man named Joe working for a crime syndicate that uses time travel to dispose of its victims in a manner that's almost untraceable.

In 2070, time travel is invented (and immediately outlawed). Because the future society also uses impeccable tracking technology that makes it nearly impossible to dispose of bodies without detection, criminal organizations have developed a system of sending their victims into the past, where an assassin — a "looper," like Gordon-Levitt's character living in 2044 — waits to kill them at a pre-appointed location.

We know that one of the first rules of time travel is never to meet another version of yourself. It could create a multiverse or a rupture in the time-space continuum, or at the very least an awkward and confusing situation. But in Looper, the crime syndicates' system depends on bending that rule: A looper's last victim will be himself from the future, which is the criminals' way of closing the contract and tying up any loose ends.

Of course, if a "loop" were not neatly closed and your future self were left alive, it would really complicate things... and even with the strength of two versions of yourself, Looper shows us just how hard that situation is to untangle.

Synecdoche, New York sets a surreal stage

Though déjà vu is a common quality of dreams, Synecdoche, New York will seem familiar for a truly rational reason: It's another brainchild from the mind of Charlie Kaufman, but this time coming to us as his 2008 directorial debut. In his review for this film, the legendary critic Roger Ebert comments that Kaufman really has "only one plot, how the mind negotiates with reality, fantasy, hallucination, desire and dreams." If that doesn't scream the name of every Inception fan, what will?

But in case you're not convinced, the postmodern vibe of Synecdoche (one character lives in a house that is perpetually on fire) will change your mind in a heartbeat. "Meta" doesn't even begin to describe it. It's more than a dream within a dream or a film about a film: You can't resurface with a "kick." You'll be completely sucked in alongside central character Caden, brought to life in an aching performance by Philip Seymour Hoffman, as he dives deeper and deeper into his life's work: his life.

A theater director, Caden wants to create something as brutally honest as possible, and his quest for realism increasingly blurs the line between imagination and reality due to the crushing weight of his own personal struggles. As years go by, he adds layer upon layer to the model of reality he has built. Synecdoche is like being trapped in a hall of mirrors, something dream-within-a-dream enthusiasts will go nuts for (although hopefully not literally).

In Enemy, you are your own worst nightmare

What's better than one Jake Gyllenhaal? Infinite Jake Gyllenhaals, obviously, but we'll settle for the two we get in another surrealist neo-noir, 2013's Enemy. This film features Gyllenhaal in the two starring roles, one as a college history professor named Adam, and the other as this character's twin and opposite: They look identical, even down to a unique scar, but Adam's doppelgänger Anthony has a much more sadistic streak.

Despite each character representing fairly established, opposing personality tropes, they swap roles often enough to make your head spin. Each man's obsession with the other feeds his counterpart's, causing the film to escalate at a surreal pace until it reaches its intentionally confusing climax.

Fans of Inception probably can't help but wonder about the role of internal fantasizing in the reality of Enemy, considering that it is such an integral part of Nolan's character and plot development in his film. Director Denis Villeneuve says that this is purposely left ambiguous: The two men meeting could be a fantastic event, or simply a subconscious one. Maybe seeing ourselves as we truly are is just as scary either way. Seeing Enemy certainly is, no matter how you interpret its Inception-esque open ending.

The Truman Show is un-reality television

Almost everyone dreams about being a movie star as a kid, but no one wants to do it the way Truman Burbank did it in The Truman Show in 1998: Without even knowing it, essentially living as a specimen in a human zoo. (Though it would probably be awesome to be an avid viewer, because your favorite show would be on 24 hours a day!)

The Truman Show starring Truman Burbank presents a fascinating paradox: its "executive producer," Christof, wants to give audiences an everyman they can relate to, one whose personality and reactions are authentic... But every facet of Truman's life is determined by what will do well in the ratings, so how authentic can any of it be?

As Truman slowly begins to discover what's amiss in his life on Seahaven Island and thus jeopardize the show, ironically, this is the first time Truman's true personality and motivations begin to shine through.

The tug of war between the production's carefully constructed world and Truman's emerging will makes for suspense and laughs in equal measure. As with Inception, we're dealing with a manipulated version of reality that's as subjective as a single person's experience.

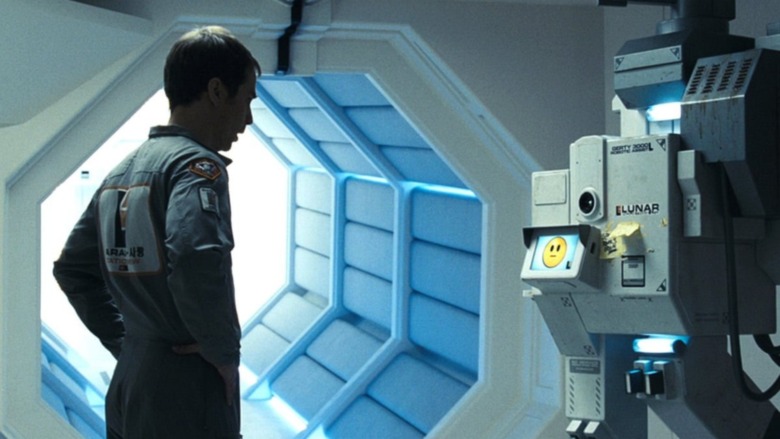

Moon is earth-shattering

One of the most compelling things about many of these films, despite how peculiar their premises might seem, is how not-so-far-in-the-future many of them are set. Based on a computer screen in the frame near the end of Moon, the relatively low-budget 2009 sci-fi film is set just a few years into the future, in 2035. (Though we have reason to believe that the year displayed on the screen may be a ruse designed to trick the protagonist — we can't give much more away than that.)

For a film with roughly one main human character whose sole company is a sole artificial intelligence voiced eerily by Kevin Spacey, Moon is utterly absorbing. Packed into a 95-minute runtime, we get a plot that upsets our notions of memory, time, and consciousness. Even the original crisis of identity experienced by the main character is far from what it seems — simply a side effect of a reality manipulated by unknown forces.

Shutter Island takes us inside DiCaprio's head again

Both Martin Scorsese's Shutter Island and Nolan's Inception were ranked among the top ten films of 2010 by the National Board of Review. Both of them starred Leonardo DiCaprio — and in both of his roles, his character is haunted by the loss of his wife, and the grip she has on him, even if only psychological, has palpable effects on the plot. And of course, both of these films deal with the subjectivity of the realities created by our minds.

DiCaprio is no stranger to acting in movies that even he doesn't understand, and there's a lot about Shutter Island that encourages us to think twice. In Inception, much of the action revolves around the psychological state of DiCaprio's character, just like in Shutter Island. The difference is that in the former, DiCaprio's character has mostly full awareness and control of when and how he moves from reality to his mind, even if he can't always control how his memories and mental state will affect him. In general, we can tell which is which (even if it takes some deducing).

In Shutter Island, however... well, the less you know going in, the better. Suffice it to say that no one could have blamed DiCaprio if he spent some time questioning the nature of reality while he was filming Inception and Shutter Island.

The Science of Sleep is another dream world

Despite its title, the 2006 film The Science of Sleep errs more on the side of art and fantasy than science. Much of it takes place in the imagination of the protagonist Stéphane, whose dreams are so vivid that they get in the way of (or augment, depending on how you look at it) his everyday life and his budding romance with his neighbor, Stéphanie.

As Stéphane's dreams begin to creep across the boundary further into real life, both he and the viewer are left unsure of what is truly real. But the overlap between fantasy and reality never strays too far from reality itself — when it does, you know Stéphane is dreaming. The best moments are when you can't quite tell: You think you know better, but can't be sure.

Take Stéphane's "one-second time machine." This little piece of magic, most likely a product of his childlike imagination, would have little effect on the world even if it were real. One second is the difference between snapping back to attention from a daydream, or closing your eyes to sneeze. So when he "proves" that it works, and a character seems to witness it, we could easily chalk that up to a placebo or even "playing along."

Or, just as easily, we could believe it's real. If there is a "science" to sleep, it's not an exact science like in Inception. And there's something beautiful about that.

Vivarium is a masterpiece in manipulation

If you go by the most literal definition, 2019's Vivarium is about "a place for life." But in practice, it's closer to the opposite for the poor couple at the center of the film, who find themselves trapped in Number 9 of a creepy endless neighborhood of identical houses known as Yonder. But at least they've got their kid... the creepy humanoid child that they must raise in order to be released.

If you're a fan of Inception, chances are you like pieces of media that are left somewhat open to interpretation. Vivarium is absolutely one of them: Even the directors encourage people to filter the film through their own culture and experience. Depending on your background, it might say any number of things to you about desire, society, family, tradition, or life.

That's a pretty broad scope for a movie that primarily takes place in the claustrophobic confines of a single, absurdly sterile house. Everything that happens in this place is carefully controlled and calculated, and there is no possibility for escape. For millennials especially, this could tap into a very specific and deep-rooted fear for their lives — not a fear of death, but a literal fear for how their lives might turn out.

You might leave this film questioning what you really want (like whether you want to watch a film like that ever again). For thrill-seeking filmgoers, it could be exactly the unnerving experience you're looking for.

Don't sleep on Waking Life

There were a number of impressive feats performed in Inception, in terms of both visual effects and the manipulation of dreams and reality. Richard Linklater's Waking Life earned renown in both of these areas back in 2001, but in a completely different manner all its own. Its unmistakable visual style was achieved with a technique called rotoscoping, which literally layers one reality on top of another: an animated one on top of a live-action one.

In contrast to Inception, there isn't a lot of action in Waking Life, which instead revolves primarily around the conversations that the main character has as he meanders through a series of dreamy vignettes. That's not to say there's no action, though, and it's all the more jarring when it happens in contrast with the wandering nature of the film.

The main character doesn't seem to have a purpose other than engaging in philosophical conversations with eccentric strangers, whose mannerisms are often exaggerated by the animation like caricatures. Many times, the question is raised of whether he is awake or dreaming — or even alive or dead. The evidence for this question mounts toward the end of the film, but if you're hoping for an explanation everyone agrees on, keep dreaming.