There Are 12 Near-Perfect Horror Movies According To Metacritic

These days, horror fans are truly living in an age of abundance.

You can barely throw a rock without hitting six different streaming services, each with their own ghastly library of ghoulish delights. So naturally, it can be difficult to prioritize.

What's a fiendish film fan to do? Well, luckily, Metacritic has you covered. With a weighted average (a.k.a. "Metascore") of aggregated critical reviews, Metacritic is one of the web's most trusted authorities when it comes to sussing out what's worth watching. If you're fanatical about a particular genre, the site features a helpful genre filter, so horror fans can peruse the best of the best in one convenient list. Per the site's point breakdown, any film that scores above an 81 has achieved "universal acclaim," making films with a score of 90 and above as close to perfect as you can get.

Below you'll find twelve terrifying flicks with unimpeachable Metacritic scores. While they all share a horrific streak, together, they make for a pretty diverse sample of what the genre has to offer, from body horror classics to quintessential slashers to poetic nightmare fuel. So read on (if you dare!) and explore the titles Metacritic has crowned as the perfect horror flicks.

Eyes Without a Face (1960)

Let's face it, France really loves its body horror. But long before the transgressive bloodbath of French Extremity, there was Georges Franju's 1960 film Eyes Without a Face, a hauntingly tactile tale of guilt, obsession and facial mutilation.

Based on Jean Redon's novel of the same name, the film follows Dr. Génessier (Pierre Brasseur), a plastic surgeon who feels responsible for the role he played in the accident that disfigured his daughter Christine (Édith Scob). With the help of his laboratory assistant Louise (Alida Valli), Dr. Génessier's desperation drives him to abduct and peel the faces off young women so he can relieve his infantilized daughter and her creepy, featureless plastic mask.

According to the booklet included in Eyes Without a Face's 2004 Criterion Collection release, when the film premiered in France the audience "dropped like flies" during the infamously graphic surgical scene. After its queasy debut, the film enjoyed an enthusiastic critical re-evaluation during its 1986 theatrical re-release, and has since claimed a spot in cinema history as a masterful, and even poetic, piece of body horror cinema, heralded by Slate's David Edelstein as "among the most disturbing horror films ever made ... [Bela] Lugosi by way of [Jean] Cocteau."

Eyes Without a Face enjoys an average 98% fresh rating on Rotten Tomatoes, and came in at number 34 in Time Out's list of the 100 best horror films. It enjoys a 90 Metascore.

King Kong (1930)

Is King Kong a horror movie? Well, it depends on who you ask. But Metacritic has firmly come down on the opinion that yes, the monstrous, terrifying god-gorilla is, indeed, a card-carrying member of the horror genre.

Co-directed by Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack, the 1933 pre-code movie tells of an adventurous film crew discovering the "eighth wonder of the world": a giant prehistoric ape who falls head over heels for the beautiful Ann Darrow (Fay Wray). Kong's romantic aspirations are foiled, however, when the crew drag him kicking and screaming to New York City, where the monstrous monkey promptly wreaks havoc.

Sporting a weighted average Metascore of 90 and a 98% approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes, Kong was a technical marvel for its time, boasting groundbreaking examples of everything from stop-motion animation to matte paintings. While the film's special effects may feel dated to the modern viewer, as Roger Ebert puts it in his "Great Movies" write-up: "in the very artificiality of some of the special effects, there is a creepiness that isn't there in today's slick, flawless, computer-aided images." Indeed, there's something unnervingly tactile about Kong's stuttering movement; something primeval and ancient that rhymes nicely with the film's mystique as one of the true milestones of movie-making.

The Birds (1963)

It may be a truism that more of something is always scarier. One pigeon? Not a problem. Hundreds and hundreds of pigeons? That's a different story.

Sitting pretty with a 90 Metacritic score, Alfred Hitchcock's "The Birds" did for our fine feathered friends what "Jaws" would do for sharks a decade later. A sub-genre defining creature feature, the film's swarms of avian adversaries aren't so much individual animals as they are a force of nature; a furious storm of beating wings and pecking beaks with unknown motivations but a clear, murderous, objective.

When the film first premiered in 1963, it was met with mixed reviews, rejected, in part, for its overt allegiance to the lowly trappings of exploitation cinema (The New Yorker's Brendan Gill declared it "a sorry failure"). And yet the passage of time won out and the critical tide turned in Hitch's favor.

Famed Italian director Federico Fellini cited the flick among his top ten films of all-time, and the "The Birds" holds the number seven spot on the American Film Institute's list of the greatest American thrillers. All told, "The Birds" remains a creepy, high-flying benchmark when it comes to killer animal flicks. So here's to never going outside ever again.

Repulsion (1965)

A controversial, gothic tale of psychosis and personal horror, Roman Polanski's first English-language film is widely praised as one of cinema's most unsettling portraits of mental and emotional disintegration.

A fragile young Belgian manicurist named Carol (Catherine Deneuve) suffers from a debilitating fear of men. A ... repulsion, as it were. When her sister and roommate Helen leaves their shabby apartment for an Italian getaway with a married man, Carol retreats deeper into her own fractured mind, where visitations (real and imaginary) have feverish and ultimately violent consequences.

Following its premiere at the 1965 Cannes Film Festival, Repulsion was met with sizable critical acclaim as "a small but piercing human tragedy," per a 1965 review in The New York Times. The film enjoys a near-perfect 95% approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes and clocks in at number 55 on Time Out's assessment of the 100 best horror movies. An impressive sophomore effort that will surely intrigue fans of squirmy, claustrophobic terror trips, Repulsion is a classic chiller well deserving of its 91 Metacritic score.

Frankenstein (1931)

There are few images more upsetting than the devastated father in Frankenstein, cradling his dead child's limp body through the streets, begging for revenge.

Don't let its age fool you. Despite being the oldest film on this list, James Whale's 1931 adaptation of Mary Shelley's novel packs an enormous, harrowing punch. Boasting a legendary and alarmingly sympathetic performance by Boris Karloff as The Monster, Frankenstein tells of an obsessive doctor driven to restore life to a creature assembled out of scraps of rotting flesh. When Dr. Frankenstein's experiment proves successful the piecemeal creature is confused, traumatized, and unable to move peacefully through the world of the living as a member of the undead.

Ingrained in the pop culture consciousness and saddled with the burden of historical relevance, it's tempting to hold Frankenstein at arm's length (ideally, palms outstretched with a shambling gait). But its reputation as a masterpiece is fully deserved. Frankenstein holds a 100% "Fresh" rating on Rotten Tomatoes and frequently places on both genre-specific lists like Bravo's "100 Scariest Movie Moments" and broader gauntlets like The New York Times' Best 1000 Movies Ever. In 2010, the American Film Institute ranked Dr. Frankenstein's joyfully morbid exclamation "It's alive! It's alive!" as the 49th greatest movie quote in American cinema. The film claims an outstanding Metascore of 91.

Son of Saul (2015)

Seeing a film about the all-too-real horrors of the Holocaust shoulder to shoulder with slashers, undead monsters, and gigantic apes feels a little strange. But in the end, if people stumble across László Nemes' necessarily-harrowing historical drama while searching for top-tier genre fare, so be it.

Son of Saul takes place almost entirely in Auschwitz-Birkenau, a complex of concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany during World War II. There, a Jewish-Hungarian prisoner named Saul (Géza Röhrig) serves as a member of the Sonderkommando, a unit of Jewish inmates forced to assist in the disposal of gas chamber victims. The plot follows Saul's dangerous and desperate attempt to provide a proper Jewish burial for a young boy he adopts posthumously as his son.

As Christy Lemire, writing for Roger Ebert, astutely notes, Son of Saul tackles the ungraspable horrors of the Holocaust by placing its horrific elements in the periphery, to the end that "the suggestion of suffering is more unsettling than wallowing in it." Likewise, The Film Stage's Giovanni Marchini Camia lauds the film as "a towering landmark for filmic fictionalizations of the Holocaust." When it debuted at Cannes in 2015, the film was awarded the Grand Prix and the prestigious FIPRESCI Prize. Later, at the 88th Academy Awards, the film won the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film. On Metacritic, Son of Saul holds an impressive score of 91.

Werckmeister Harmonies (2000)

Even without directly invoking the obvious trappings of the genre, Hungarian directors Béla Tarr and Ágnes Hranitzky expertly craft an atmosphere that is unmistakably, and oppressively, horrific.

Werckmeister Harmonies takes place in an anonymous provincial town in the dead of winter. Despite the biting cold, townspeople gather to gape at the main attraction of the traveling circus that now occupies the town square: the massive, stuffed carcass of a whale. People come from far and wide to gape at the bloated, smelly monster. Over time, the tension between the townsfolk and the gawking visitors becomes unbearable and erupts in violence.

Like much of Tarr's work, Werckmeister Harmonies is the dictionary definition of "slow cinema," composed of thirty-nine long, dreamlike single-camera shots that play out languidly over the course of the film's 145-minute runtime. When the film was released in 2000, it was met with critical acclaim and praise for, as The Guardian's Richard Williams puts it: a "bleak vision of chaos and capitalism." According to a statistical breakdown from They Shoot Pictures, Don't They, the film is presently the 34th most critically acclaimed film of the 21st Century. Unsurprising, then, that it boasts a 92 score on Metacritic.

Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956)

In a chilling blend of science fiction and horror, Don Siegel's 1956 film about an interstellar onslaught of "pod people” is one of the most astute political allegories of 1950s America. Released at the height of the cold war, the film's acute vision of insidious conformity struck an anti-communist nerve while flirting with a more seditious critique of the tyranny of the McCarthy era.

Based on Jack Finney's serialized 1954 sci-fi novel, The Body Snatchers, the film follows a small-town doctor (Kevin McCarthy) as he slowly uncovers the truth about the recent unsettling changes in his sleepy community. Namely: the town is quietly being invaded by an alien presence who gestate in massive seeds and take over people's bodies as they sleep, producing emotionless, indistinguishable carbon copies of the original person.

Boasting a 92 Metascore and an impressive 98% approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes, in 2008 the American Film Institute recognized the film as the ninth best entry in the science-fiction genre. Steeped in unchecked paranoia and alienation, Invasion of the Body Snatchers is a taut and atmospherically tense horror film with very little horror on-screen. All the better to wreak horrific havoc on your imagination.

Forged in the fears of an infamously anxious era, Invasion of the Body Snatchers is one of the best amalgamations of three distinctly spine-tingling genres: film noir, horror, and sci-fi.

Bride of Frankenstein (1935)

"We belong dead": three immortal words that encapsulate the macabre heartache of Bride of Frankenstein, James Whale's crushing follow-up to his original gothic monster flick. That's right, a horror sequel boasts the fourth highest score on Metacritic. Amazingly, as Richard Corliss and Richard Schickel note in Time's round-up of the top 100 all-time greatest films, Bride is "one of those rare sequels that is infinitely superior to its source."

Picking up right where the first film left off, Bride of Frankenstein reconnects with the deranged doctor (Colin Clive) who has fallen back under the spell of his former mentor, Dr. Pretorius (Ernest Theiger). When Pretorius encourages his pupil to resume his experiments and create a mate for the Monster (Boris Karloff), the shattered Frankenstein finds that he cannot refuse.

Frequently identified as the crown jewel of Universal monster movies, Bride of Frankenstein's overarching theme about a relationship society doesn't deem natural retains its relevancy to this day (all the more heart-breaking considering Whale himself was openly gay, an element beautifully explored in the 1998 Oscar-winning film Gods and Monsters). With a fantastic 95 on Metacritic, Bride of Frankenstein is a must-watch for anyone looking to see what all the fuss is about when it comes to classic-era horror films.

Don't Look Now (1973)

Adapted from Daphne Du Maurier's short story of the same name, 1973's Don't Look Now laid the foundation for one of the most unsettling templates in horror: a family tragedy, the hope of healing, and the sharp descent into terrifying territory. It's a trauma-laced slow dive that feels, unavoidably, like the logical extension of the initial, unthinkable loss: a protracted grief-fuelled nightmare that muddles the line between a psychological break and the genuinely supernatural.

Don't Look Now follows a married couple (Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie) who move to Venice after the death of their young daughter Christine. Confined in the city's elegant decay, they both begin to experience a series of terrifying and increasingly dangerous occurrences that defy explanation. Tempted by the irrational notion that their daughter might still be alive, the couple form a disturbing friendship with two sisters, one of whom claims to be clairvoyant.

Directed by Nicolas Roeg, a former cinematographer with an undeniable eye for color and composition, Don't Look Now is a breathtaking marriage of giallo tropes and pulpy intrigue. The film features one of the most memorable final scenes in genre film; a "shocking climax", as noted by The A.V. Club's A.A. Dowd, that cements the film's reputation as "an all-time creep-out." With a flawless 96 Metascore, Roeg's stylish examination of the maddening power of loss is essential viewing for genre fans.

Rosemary's Baby (1968)

As genre scholar Grady Hendrix notes in Paperbacks from Hell, 1967 was "a spark to the heart for horror fiction."

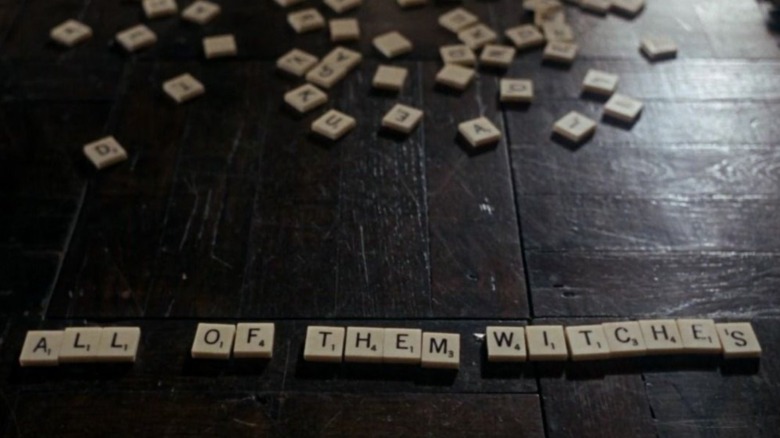

For the first time since Daphne du Maurier's Rebecca in 1934, a horror novel graced the annual best-seller list of Publishers Weekly: Ira Levin's Rosemary's Baby. A precision thriller about the devil impregnating a woman on the Upper West Side, Levin's novel was swiftly adapted into a film just one year after its publication. Starring Mia Farrow as the titular Rosemary and John Cassavetes as her fame-hungry husband Guy, Roman Polanski's satanic slow-burn frequently tops "best of" lists for a reason. After all, Satan has absolutely nothing on the blood-curdling terror of gaslighting, gender roles, and losing agency over your own body.

In 2014, Rosemary's Baby was selected by the Library of Congress for preservation in the National Film Registry. And in 2010, The Guardian ranked it as the second-greatest horror film of all time. Ruth Gordon's performance as Minnie Castevet, a nosy neighbor quite literally from hell, earned her an Academy Award for best supporting actress. It would be the last Oscar awarded to a horror movie until 1991's The Silence of the Lambs.

Every film ambling under the umbrella of "elevated horror" owes an immense, demonic debt to Rosemary's Baby and its revolutionary vision of satanists not as twisted fiends but the kind of recognizably modern folks you might pass in the street without sparing a second glance. With uncomfortably long takes, claustrophobic set design, and immersive trance-like pacing, this is a film that wheels and deals in pure psychological horror worthy of a 96 Metascore.

Psycho (1960)

Psycho's impact on genre cinema truly cannot be overstated. It challenged the censorious limits of the Production Code, pioneered marketing techniques that would ultimately define the "event film," and effectively laid the groundwork for a whole host of sub-genres from slashers to serial killer profiles. It makes perfect sense, then, that Alfred Hitchcock's enduring masterwork boasts a near-flawless 97 on Metacritic.

The film begins with a deceptively conventional set-up: Marion Crane (Janet Leigh), an underestimated real estate clerk, embezzles a sizeable chunk of change from her employer in the hope of starting a new life. When she's caught in a torrential downpour, she takes refuge at the Bates Motel, an isolated establishment run by Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins), a quirky mama's boy who probably wouldn't even hurt a fly. Probably.

Transitioning from a straight-forward noir to something altogether nasty, Psycho's unsettling portrait of a predatory Peeping Tom remains as forceful today as it was in 1960. While the film's devious rug pulls are now widely known, Psycho continues to function as one of the most gripping and suggestive entries in the horror-thriller sub-genre it largely helped define.

With a leering camera that often mirrors its predatory subject, Psycho actively revels in the sinful, voyeuristic allure of cinema itself, twisting the act of watching into something deviant and transgressive. As Rotten Tomatoes' critics consensus astutely states: with Psycho, "Hitchcock didn't just create modern horror, he validated it."