The Ending Of The Lobster Explained

The success story of Yorgos Lanthimos is an unlikely one. After years as a journeyman video and TV commercial director with forays into experimental film and theater (via Raindance), the Greek filmmaker finally managed to get his mainstream breakthrough in 2009 with his third feature, "Dogtooth," a grotesque psychological drama that left international audiences aghast and scored an unexpected Oscar nomination for Best Foreign Language Film. The last thing anyone expected at the point was for Lanthimos to break out into the U.S. mainstream, but that's just the path he took, culminating in the huge critical and commercial success of Fox Searchlight's "The Favourite" and the announcement of his new Frankenstein reimagining starring Emma Stone and Willem Dafoe (via Deadline).

Lanthimos' transition from European shock-art maverick to Hollywood auteur began with the attention grabbed by 2015's "The Lobster," his first English-language film. An off-kilter dystopian tale about a world in which single people are forced by the government to find romantic partners or else be turned into animals, "The Lobster" is utterly bizarre, with a sinuous screenplay that earned Lanthimos his second Oscar nod along with co-scribe Efthymis Filippou. But it's the unconventional direction that really makes the movie so singular: instead of emphasizing any of the many metaphors, dark jokes or satirical points about our matrimony-obsessed culture, Lanthimos shoots all the action at a clinical remove, leaving the audience to soak in the weirdness and figure things out.

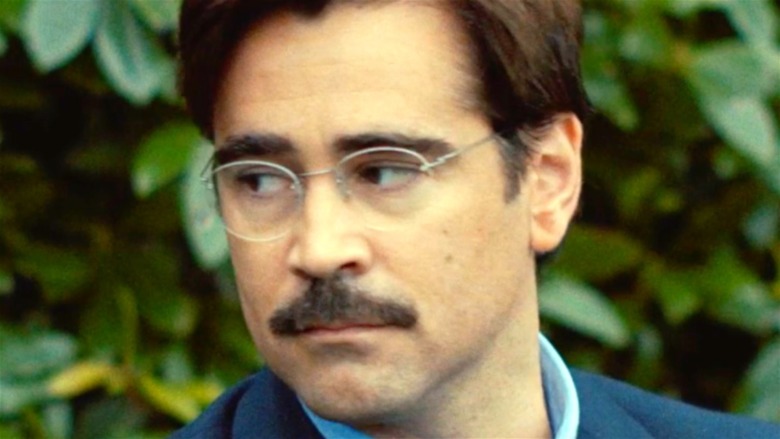

As a result, the story's turns can be tough to make sense of, all the more so when the movie quietly morphs into a sincere romance in its second half. And the ultimate fate of David (Colin Farrell) and the Short Sighted Woman (Rachel Weisz) arrives like a sudden pang, bereft of traditional catharsis, begging to be made sense of.

The ending of "The Lobster" illustrates the pervasiveness of social norms

The world of "The Lobster" can't be understood on the terms of a straightforward drama. Everything about it is heightened and metaphorical: The Hotel and its rules are a more overt expression of our own society's constant pressures on single people, while the chaste forest milieu of the Loners reflects some people's impulses to escape the "dictatorship of love" by disowning and vilifying intimacy at large. In either realm, whether by being senselessly bureaucratized or outright banned, "romantic relationships" are revealed as a rigid social rite, unrelated to the base facts of love, lust and human connection.

David and the Woman's story isn't just any old story of star-crossed lovers persecuted by the powerful. It's the story of love, as a concept, coming into conflict with our society's absurd preconceptions about it. While the characters of "The Lobster" hold the misguided belief that "love" means "finding someone with whom you share superficial characteristics and then forcing yourself to get together with them," the fact remains that love exists in human life, and they are capable of feeling it. David and the Woman may initially get together because they're both short-sighted and brought up to think that makes them "compatible," but they remain together, even under the Loners' prohibition, because they truly feel a connection to each other.

That's what makes the ending so heartbreaking. After finally escaping the Loner Leader (Léa Seydoux) and running away to live as they choose, you would think David and the Woman might also free themselves from society's preposterous ideas about love, seeing as there aren't any powerful figures left to dictate how they should relate with each other. But, as is often the case in real life, those ideas are so ingrained that they believe them even when they're not forced to. David truly thinks he needs to blind himself with a knife to remain with the Woman, ignoring the fact that they're simply free to be with each other. It's a particularly scary moment for a non-horror film, in keeping with Lanthimos' dark filmography. And yet, there is a hopeful undercurrent.

Ultimately, David and the Woman's love for each other is real

On one hand, yes, David and the Woman can just be together, her blind, him not, without needing "compatibility." However, there's a huge difference between this possible sacrifice and the concessions David had to make to the Heartless Woman (Angeliki Papoulia) earlier on. In the Hotel, David had to find a partner, to avoid being turned into a lobster. He was effectively forced into repressing his emotions and putting on a performance for his new match. With the Short Sighted Woman, meanwhile, there's nothing driving him, other than himself. He wants to do whatever it takes to be with her.

Moreover, the Hotel imposes strict rules on David from the outside: He knew the woman would call off their engagement and send him to the transformation chamber if he didn't follow orders. But David's thoughts about his relationship with the Short Sighted Woman are spontaneous, natural, and genuine. And, while there's indoctrination informing the belief that he must become blind as she has, that belief is also a product of their interactions — specifically the scene where they scramble to find a new thing in common, and come up blank. Therefore, David's idea to blind himself is, in a twisted Lanthimosian way, a beautiful commentary on the sacrifices people in a relationship make for one another. He loves her so much that he's about to stab his own eyes just to accommodate her.

We never see if he goes through with it. As in real life, such sacrifices are hard to make, and not every lover is able.

"The Lobster" leaves us on the Woman's pensive expression, as she ponders the challenges ahead. Her doubt becomes an open vessel for each viewer's own feelings about love and relationships.