The Untold Truth Of The Godfather Trilogy

Francis Ford Coppola's first two Godfather films rank among the greatest movies ever made. This epic saga follows the rise and fall of the Corleone family, and along the way, it paints a staggering portrait of American life, all while spinning an incredible story of family and foul play, omerta and olive oil. But while these movies are a thrill to watch, the behind-the-scenes stories are equally fascinating. Keep your friends close and your enemies closer as we dive into the untold truth of The Godfather trilogy.

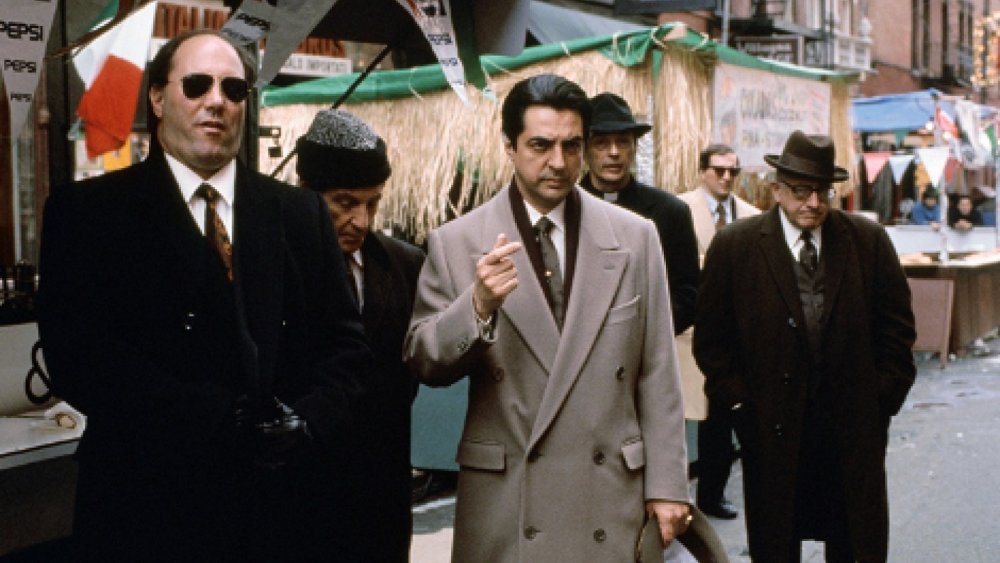

The mafia declared war on the movie

As the quintessential gangster movie, The Godfather is 100 percent responsible for creating the modern-day idea of the Mafia. In fact, the film was such a pop culture success that actual wiseguys started borrowing phrases from the movie, like "I'm going to make him an offer he can't refuse." And that's pretty ironic, considering the Mafia tried its best to prevent The Godfather from ever making its way to the silver screen.

Before filming started, The Godfather came under attack from the Italian-American Civil Rights League, a group opposed to Italian stereotyping. However, the league wasn't completely on the up-and-up, as it was founded by Joseph Colombo, head of the Colombo crime family. While he probably did want to fight racism, Colombo also wanted to keep the mob out of the limelight, and under his orders, the league launched protests and rallies to oppose The Godfather. Frank Sinatra even performed at a league event in Madison Square Garden, a rally that brought in $500,000 for the cause.

But when legal means failed, Colombo got his hands dirty. Gangsters started tailing Godfather producer Al Ruddy and smashed all the windows out of his car. Paramount executive Robert Evans received a phone call from a thug who threatened to hurt his kid. Even worse, the Paramount offices in New York were evacuated twice after receiving bomb threats.

Eventually, Ruddy decided to cut a deal and met Joe Colombo face to face. The two agreed if Ruddy cut any mention of the word "Mafia," then The Godfather could continue shooting. (It was a pretty great offer, as the term only appeared in the screenplay once.) Finally, Coppola could get busy, and as for Joe Colombo, he was eventually gunned down at a league rally just blocks from where The Godfather was shooting its climactic scenes. The gangster spent several years in a coma before dying in 1978, but his memory lives on in Godfather lore—especially since he inspired the character of Joey Zasa, the villain of The Godfather Part III.

The story behind Luca Brasi

The Godfather trilogy is jam-packed with iconic characters, from Tom Hagen to Johnny Fontane, but none loom so large (literally) as Luca Brasi. The number one hit man for the Corleones, Brasi steals the show every time he lumbers into the frame, and that's totally thanks to the man playing the gigantic gangster, a real-life bruiser named Lenny Montana.

Standing 6'6" and weighing over 300 pounds, Montana was a professional wrestler called "The Zebra Kid." He also made a few extra bucks working for the Colombo crime family, acting as security and, occasionally, as an arsonist. According to the big guy himself, one of his favorite methods of setting buildings ablaze involved tying a tampon to a mouse's tail, setting the tampon on fire, and letting the rodent loose.

In other words, Montana was a scary guy, and he'd recently been released from prison before arriving on The Godfather set. According to Vanity Fair, he was working as a bodyguard for a Colombo don, although according to Time, he was escorting Joe Colombo himself. Either way, Coppola spotted the behemoth and immediately wanted him to play Vito Corleone's right-hand man. As far as an audition, Coppola asked the gangster if he could spin the cylinder of a pistol. Montana answered incredulously, "You kiddin'?"

Of course, Montana was a leg breaker, not a thespian, so when it came time to act alongside Marlon Brando, Montana flubbed his lines. The stuttering you hear in the film is completely real, but Coppola kept it in the movie. After the botched take, Coppola fixed things by having Montana film a scene where he's nervously rehearsing the speech he plans on giving to Don Corleone, making it look like the screw-up was due to the gangster's nerves...the fictional gangster, not the real one.

Connections to the mob

After Joe Colombo gave The Godfather his seal of approval, gangsters started showing up on the set, and the filmmakers were only too happy to put them to work. After all, if you're making a movie about the Mafia, who better to cast than real-life wiseguys?

In addition to hiring Lenny Montana, Coppola and company also hired Alex Rocco, the guy who played casino owner Moe Green. Before moving to Hollywood, Rocco was involved in the Winter Hill Gang, a notorious Boston outfit, and according to Paste Magazine, he was once accused of being the getaway driver for a gangland hit.

Another actor with mob ties was Gianni Russo, the guy who played the weaselly Carlo Rizzi. Admittedly, Russo has told some pretty wild stories (he claims he's slept with Marilyn Monroe, Zsa Zsa Gabor and Liza Minnelli), but according to the actor, he once killed three men, worked alongside Frank Costello, was connected with John Gotti, and got the part of Carlo courtesy of Joe Colombo.

But it wasn't just the character actors who palled around with professional thugs. While preparing to play Sonny Corleone, James Caan befriended Carmine "The Snake" Persico, a man who earned his nickname by being handy with a garrote. Persico eventually became the head of the Colombo family, and he hung around with Caan so often that government officials thought the actor was actually a rising Mafioso. Years later, Caan would even support Persico at his 1985 trial, where the gangster was charged with everything from extortion to racketeering.

Even Coppola had a close criminal encounter. While he enjoyed casting fringe Mafia members, he wasn't fond of the big bosses. This made things awkward while filming The Godfather Part III, as crime boss John Gotti asked to meet with the director. Coppola explained he was too busy to chat and had an assistant send the don away. So why was Coppola reluctant to meet with Gotti? As the director explained, mobsters are like vampires, and "a vampire can only come into your life if you invite him to step over your threshold...but if you don't invite him...then they won't."

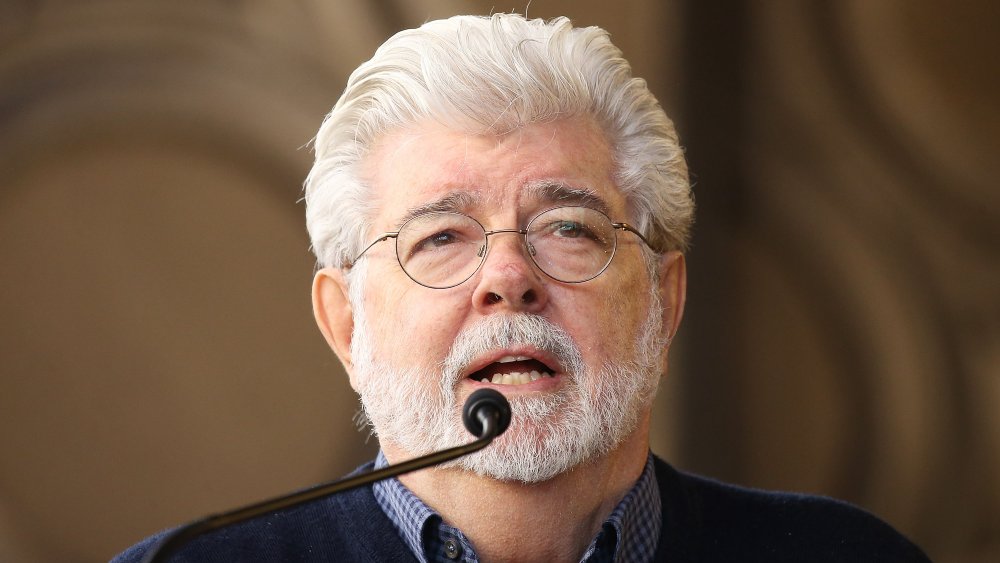

George Lucas helped out

When Coppola was initially approached to helm The Godfather, the director passed, as he wasn't a fan of the book. However, he changed his mind after realizing he needed some cash to save his film studio, American Zoetrope, from serious debt—and one of the people who convinced Coppola to tackle The Godfather was none other than George Lucas, his friend and Zoetrope partner. "We really need the money," Lucas told his buddy. "What have you got to lose?"

So in addition to creating Luke Skywalker and Princess Leia, George Lucas is kind of responsible for the greatest gangster movie ever made. But his involvement with the project doesn't stop here. Coppola actually asked Lucas to help out on the set, and the not-yet-famous filmmaker played a key part in the "going to the mattresses" montage. In that particular segment, the audience is given updates on a raging Mafia war via newspaper headlines, and Lucas was the guy who actually filmed those inserts.

Finally, Lucas helped edit the scene when Michael Corleone rescues his hospitalized father from oncoming assassins. As Coppola worked on this segment, he thought it would be nice to include shots of empty hallways, complete with the sound of oncoming footsteps. This would add some serious tension, but unfortunately, Coppola forgot to get these shots while filming.

Desperate, Coppola turned to Lucas, his only hope. And after digging through the footage, Lucas actually found a few shots of empty hallways. These moments were just seconds long, coming immediately after Al Pacino left the scene and Coppola called cut. Thankfully, Lucas used his Jedi mind powers and edited these split-second flashes into the film, allowing Coppola to craft a truly suspenseful scene.

The restaurant scene

It may seem ridiculous in hindsight, but in 1971, Paramount executives were pretty nervous about The Godfather and its ambitious young director. After all, they wanted the film set in the '70s. Coppola put it in the '40s. They didn't want Al Pacino or Marlon Brando, but Coppola cast them anyway. Even worse, the studio heads weren't impressed with any of the early scenes, and there was serious talk that Coppola was going to get canned.

Thankfully, the restaurant scene changed everything. When the studio executives watched Michael Corleone murder two rivals during an Italian dinner, they were thoroughly impressed with Pacino's performance. Convinced Coppola knew what he was doing, Paramount eased off, and as Coppola later admitted, "This scene certainly saved me."

No doubt the special effects played a large part in wowing such a cynical audience. Wanting to capture the murder of Virgil "The Turk" Sollozzo in all its gory glory, the effects team rigged up a special tube of red powder which was placed behind actor Al Lettieri's head. When it came time for the kill, a burst of air launched the bloody powder into the atmosphere. Of course, first someone had to shoot the actor in the head with a wax bullet, taking care not to hit Lettieri's eyes. The actor escaped the scene unscathed, but sadly, there was one unexpected casualty.

After offing his enemies, Pacino was supposed to escape by leaping onto a nearby car. Unfortunately, he missed the jump and majorly injured his ankle. The accident left him unable to walk for a couple of weeks, forcing him to use a wheelchair and crutches. Adding insult to injury, you can't even see Pacino make the leap as he's hidden by the car. Well, at least he got an Oscar nod and international fame for his troubles.

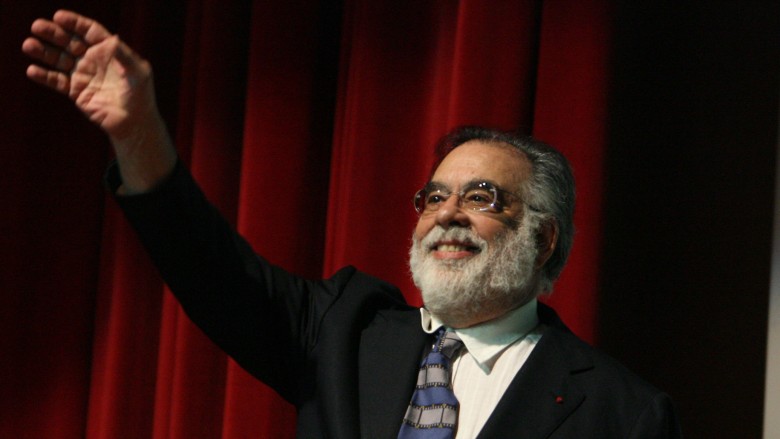

Coppola didn't want to make a sequel

In this era of sequels, remakes, and reboots, people often pine for the glory days of cinema. But even in the 1970s, arguably Hollywood's greatest decade, the moviemaking machine was only interested in money. So when The Godfather was a smash hit, earning rave reviews and stacks of cash, the folks at Paramount desperately wanted to do a sequel. However, convincing Francis Ford Coppola to return was a little complicated.

Thanks to all the drama surrounding the first Godfather film, Coppola wasn't sure he wanted to get involved in the same old mess. He also worried if the sequel failed, it might tarnish the legacy of his original masterpiece. And perhaps most importantly, Coppola wasn't really interested in making another gigantic movie. Instead, he wanted to focus on more personal projects. But the folks at Paramount wouldn't take no for an answer, and they made him an offer he couldn't...well, you know.

At first, they asked Coppola to produce the movie. They'd even let him pick a director. Coppola agreed and offered up Martin Scorsese, but studio execs said Scorsese was "a horrible choice." Finally, Paramount played its trump card, offering Coppola a million bucks. With that kind of money, Coppola would finally be able to focus on his own films. In addition to the paycheck, Coppola convinced the studio to finance his upcoming thriller The Conversation, and talked them into letting him work on additional projects, like writing the screenplay for 1974's The Great Gatsby.

Really, it was too good a deal to pass up. Just when Coppola thought he was out, they pulled him back in.

Robert De Niro wanted in from the start

Cinema history is full of "what ifs," especially where The Godfather is concerned. When casting the first film, Coppola had a list of potential actors for each part. For example, he considered both Brando and Laurence Olivier for the part of Vito Corleone. And in addition to Pacino, he was looking at Dustin Hoffman, Martin Sheen, and Michael Parks for the role of Michael. (The studio, on the other hand, wanted someone like Ernest Borgnine for Vito, and either Robert Redford or Ryan O'Neal for the youngest Corleone son.) But of all the possible picks who didn't make the cut, the closest to landing a role in the first film was Robert De Niro.

After considering him to play Michael, Coppola asked De Niro to audition for Sonny, Vito's hot-headed son. According to Coppola, De Niro was "spectacular," but he played "Sonny as killer." It was too intense, and the part eventually went to James Caan. (That was actually a compromise. Paramount agreed to let Pacino play Michael if Coppola chose Caan. In the end, everybody won, as Caan killed it as Sonny. No pun intended.)

As for poor De Niro, after Coppola saw his breakout performance in Martin Scorsese's Mean Streets, he brought the actor back for The Godfather Part II to play a younger version of Vito Corleone. Since the character only spoke Sicilian, De Niro proved his dedication by moving to Sicily and immersing himself in the language. Evidently, the research paid off as De Niro won an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor, making Brando and De Niro the only two performers to win Oscars for playing the same character.

Financial difficulties hurt the cast

They say the love of money is the root of all evil. Well, it can certainly screw up a good movie, something Coppola found out the hard way. When working on The Godfather Part II, the director planned on bringing back the original surviving characters. Unfortunately, he ran into a 200-pound problem named Richard Castellano.

In the original, Castellano played Peter Clemenza, a rotund capo who teaches Michael how to cook meatballs. Believe it or not, Castellano was the highest-paid actor in the first film, as far as straight salaries go, and when it came time to make the sequel, he wanted an even bigger payday. On top of that, he also wanted to hire his own writer to craft his own lines. As you might expect, this didn't sit well with Coppola, and poor Clemenza passed away between parts one and two. Needing a new character to take Clemenza's place, Coppola created Frankie Pentangeli (played by Michael V. Gazzo), a gangster with an incredibly critical role in the sequel.

Things got even worse when it came time to make The Godfather Part III. This time, Robert Duvall wanted to make as much money as Al Pacino. Tragically, Coppola and company decided to kill off the character of Tom Hagen rather than meet Duvall's demands, replacing the consigliere with the actor George Hamilton. As Michael Wilmington of the Los Angeles Times pointed out, this was a huge mistake.

"[Hagen] is so inextricably tied into the whole texture and emotional weave of the story," Wilmington wrote, "that he's always seemed indispensable, perhaps even part of some inevitable, slowly ripening climax, a last bloody act where Hagen would play a combatant in a final betrayal and clash with Michael."

Man...Part III could've been awesome.

The Godfather Part III was almost a very different movie

Some say it's garbage. Others say it's vastly underrated. Whatever your opinion, we can all agree The Godfather Part III is the weakest film in the trilogy. The final installment follows an elderly Michael Corleone who's trying to go straight but gets yanked back into the underworld. Mix in a banking scandal, a real estate company, and a few Catholic conspiracy theories, and bada-bing, you've got The Godfather Part III. But if the folks at Paramount had gotten their way sooner, this movie would've been way crazier.

Wanting to get more of that sweet Godfather money, Paramount asked Coppola to direct the third film. Understandably, Coppola passed, saying the story was done. Studio executives then started looking for a replacement, and at the same time, they started sorting screenplays. Around 18 scripts were written for Part III, all with some pretty wild plot twists. In one version, Connie Corleone poisons Michael to death. In another, Michael shoots himself in the head. Another screenplay had the Mafia team up with the CIA to assassinate a druglord, and another had Michael getting blown to bits in a fiery explosion.

Strangest of all, Paramount eventually offered the directing job to Sylvester Stallone. They also wanted the Rocky star to write and act in the film, perhaps alongside John Travolta. Even Eddie Murphy was mentioned somewhere along the line, but all these zany ideas disappeared when Coppola finally decided to direct the picture. Once again, the man needed money for his bankrupt movie studio, so he set about on his final Godfather film, hoping to end the Corleone saga once and for all.

The series was marred by an actual murder

While Sofia Coppola is a talented director, there's no denying her performance as Mary Corleone in The Godfather Part III is anything but awful. And while it's tempting to blame her dad, Sofia wasn't Coppola's first choice. In fact, the director considered multiple actresses for the part, including Julia Roberts and Madonna, before settling on an up-and-coming star named Rebecca Schaeffer.

Tragically, as Schaeffer was preparing for her audition in 1989, a stalker named Robert John Bardo was lurking outside her home. Bardo was obsessed with Schaeffer and had gotten her address from a private detective. On July 18, Bardo knocked on her door, and when Schaeffer answered, he shot the actress to death. After Bardo's arrest, he was put away for life, with no possibility for parole, but while the murder was devastating, The Godfather Part III had to go on.

Next, Coppola gave the part of Mary Corleone to Winona Ryder. But as fate would have it, Ryder had just finished making three films back-to-back, and the exhausted actress came down with a respiratory infection and a 104-degree fever. "I literally couldn't move," Ryder explained, and since she was too ill, Coppola gave the role to his 18-year-old daughter.

This was actually fitting in a weird way, as Sofia Coppola had already appeared in the first two Godfather films. She played Michael's infant nephew in the first move, and she showed up as an immigrant in Part II. With her performance in Part III, Sofia Coppola became one of the few actors to appear in all three Godfather films. It's just too bad that she can't, well, act.